|

This is the first of four Blu-ray box sets, eight films per set in chronological order, which the BFI are releasing over the next twelve months.

Ingmar Bergman was one of the cinema’s great writer-directors. Note that phrasing: while there are many writers who direct their work, and directors who write, relatively few can be called writer-directors, in that the two disciplines are for them on a par with each other. A lot of the time, one is superior to the other. In his early career that was certainly the case with Bergman, who freely admitted that his skills as a director took time to develop and that two of the films in this set are better for other people directing them. Bergman was something of a late developer. He wasn’t like Orson Welles, say, delivering a masterpiece first time out in his mid-twenties. Bergman didn’t write and direct a film which could number among his great works until he was past thirty, and the two films which particularly made his reputation worldwide, The Seventh Seal and Wild Strawberries, both came out in 1957, the year he turned thirty-nine.

Late developer he might have been, but Bergman was prolific. He’s not in the select list of directors who made more feature films than they lived years (for example, Rainer Werner Fassbinder, Ford Beebe, Allan Dwan and the still alive and active Takashi Miike), but he was very productive by any other sensible standard. There is an entire documentary, Bergman: A Year in a Life (which is released by the BFI on Blu-ray in both its two-hour cinema version and the four-part, four-hour television version, Bergman: A Life in Four Acts) devoted to that one key year of 1957, bookended by the releases of the two films mentioned above, but which included another feature (Brink of Life), a feature made for the then-new medium of television (Mr. Sleeman is Coming), four radio plays and two stage productions, one of them being a five-hour version of Peer Gynt. By then he was on his third wife and sixth child, and was having affairs with other women, sometimes more than one at once. He also ended up in hospital with stomach and intestinal ulcers and while there wrote the script of Wild Strawberries, which started shooting a month later. He was clearly on fire, and presumably he found time to sleep. He certainly regretted his neglect of his home life and his children for the sake of his career, and this is reflected in some of his later films, Autumn Sonata for one.

Ernst Ingmar Bergman was born in Uppsala on 14 July 1918, the middle child of three, with an older brother, Dag, and younger sister, Margareta. His father, Erik, was a Lutheran minister who had been a chaplain to King Gustav V of Sweden. Ingmar’s comments about his childhood and schooldays, in his autobiography The Magic Lantern, have to be treated with some caution. Ingmar claimed that his father was a brutal man, frequently punishing him. However, Dag, who later became a diplomat, said in an interview which Ingmar suppressed in his lifetime that this wasn’t true: Ingmar was the favoured child and it was he, Dag, who had borne the brunt of their father’s ill-treatment. The same applied with the teachers at school. Ingmar drew on this period of his family life in his final cinema film, Fanny and Alexander, and while some aspects of Alexander do mirror those of Ingmar (such as his playing with toy theatres from a young age) in other aspects, such as the father’s brutality, Ingmar’s stand-in might actually be the younger sister Fanny. This wasn’t the first time that Bergman dramatised some aspect of his life and preoccupations via a female protagonist.

At Stockholm University, where he studied art and literature, Bergman became involved in student theatre and first gained an interest in cinema. While working as an assistant director at a local theatre. By 1944, aged twenty-six, he had become the manager of the Helsingborg City Theatre, the youngest theatrical manager in Europe at the time. This brought him to the attention of Svensk Filmindustri (SF from now on) who hired him, first rewriting other people’s scripts, then writing his own.

Between 1944 and 1950, Bergman directed nine feature films and wrote the scripts for three directed by others. Six of the former and two of the latter are in this set. SF clearly regarded Bergman as a developing talent because at first, until Prison (1949) they allowed him to write original scripts and to direct films but not to do both in the same film. Bergman is certainly in a learning process with these films, and you can see him trying out various genres and modes to see what he could take from them: romantic melodrama in Music in Darkness, for example, or Italian-style neo-realism in Port of Call. However, you can see the start of several important working relationships, with particular actors, for example, or with the first of the two great cinematographers he worked long-term with, namely Gunnar Fischer. A heterosexual man with a (to say the least) complex love life, Bergman clearly took a strong interest in women and their inner lives, and you can see early examples of that here.

This period of Bergman’s career is not his best known: not just because he hadn’t fully matured as an artist, but until relatively recently availability. Most of these films didn’t receive UK cinema releases at the time they were made. Some did about a decade or so later in the wake of Bergman’s international fame, and others didn’t gain a commercial release until they reached DVD in the early years of this century. There are reasons for this, not just because Bergman was a relative unknown. There’s a remarkably adult tone to much of this work: sexual references, the taboo subject of abortion more than once, even some casual nudity. While subtitle translations could be sanitised, this was beyond what mainstream US cinema would allow, as it was then controlled by the Production Code. This also certainly went beyond what the British Board of Film Censors would then allow, given that their highest rating at the time was the A certificate. They did have the H, which stood for “horrific”, advisory but which some local authorities banned to under-sixteens. Not every H was a horror film, as occasionally the BBFC seemed to use it as an all-purpose adult certificate before they officially had the X, which was introduced in 1951. This new certificate did allow some of these films to play in commercial cinemas later in the decade.

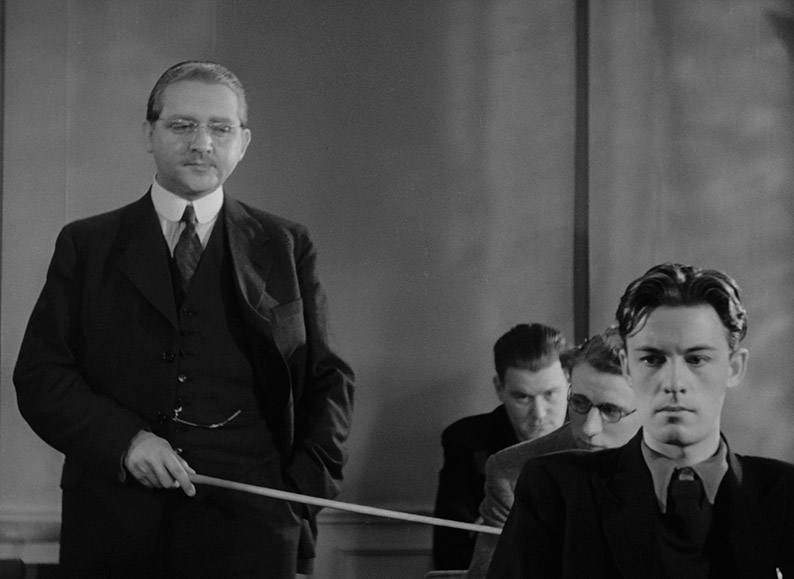

Jan-Erik Widgren (Alf Kjellin) is a student at a Stockholm school, at odds with a sadistic Latin teacher (Stig Järrel), nicknamed “Caligula” who frequently picks on him. Jan-Erik becomes involved with Bertha (Mai Zetterling) who works at the local tobacconist. However, she fears an older man, though will not reveal his name. But soon, Jan-Erik finds out that it is Caligula...

Torment (Hets, sometimes known in English as Frenzy) was Bergman’s first produced screenplay, directed by the fifteen-year-older and much more experienced Alf Sjöberg. Primarily a stage director, Sjöberg had directed his first film fifteen years earlier, at the very end of the silent era. Torment was a breakthrough film, not just for Bergman, but for Swedish cinema in general. During the War, Sweden had made films mostly for local consumption which did not travel abroad, though its being a neutral country may have had an effect. Torment won the Grand Prix at Cannes in 1946, shared with ten other films (including Brief Encounter, The Lost Weekend and Rome, Open City – quite a year). When it opened in the UK the same year, the Monthly Film Bulletin (June issue) pointed out that it was the first Swedish film to gain British distribution since 1937. However, as a first-time screenwriter, Bergman didn’t receive much attention. He doesn’t even get a mention in that MFB review except tangentially: “the story is thin and owes everything to Sjöberg’s perfect direction and the acting”. Some reviews noted a similarity between Caligula and Heinrich Himmler, who had begun his career as a school teacher, though this was Sjöberg’s idea rather than Bergman’s. Bergman had in fact been an admirer of Hitler during the War, and at first after it had ended claimed the reports of concentration camps was Western propaganda. When he realised the truth, Bergman was so ashamed that he refused to become involved in politics ever again.

Bergman wrote Torment as a spec script based on a short story he had written. How much Jan-Erik’s treatment at the hands of Caligula is autobiographical is open to question (see above). Bergman certainly claimed that it was at the time, which caused the headmaster of his old school to object, and this provoked a debate on Swedish schooling.

SF acquired the script and Bergman was hired as an assistant director, his first time on a film set. Sjöberg had a taste for more adventurous material, and it’s clear his direction, often Expressionist-influenced, with plenty of high angles and shadowy lighting, is far in advance of what Bergman was capable of at the time. When Sjöberg was not available for reshoots of the ending (a more optimistic one was required, after previews), Bergman stood in for him, the first time he had directed anything on screen, though he had on stage by then. However, Bergman’s writing abilities are certainly to the fore, and the characters are more finely drawn when they could easily have been more one-note. If Bergman was watching Sjöberg work and taking note, others were no doubt doing the same: both Kjellin and Zetterling went on to direct films themselves.

Adapting the radio play Moderhjertet (variously translated as A Mother’s Heart or A Mother’s Instinct) by Leck Fischer, Bergman delineates two emotional triangles which intersect in eighteen- year-old Nelly (Inga Landgré), who lives in a small town with her foster mother Ingeborg (Dagny Lind). Ingeborg runs a boarding house and is also a piano teacher but struggles to make ends meet, and her health is suffering. Meanwhile, Nelly’s birth mother Jenny (Marianne Löfgren) arrives to take Nelly away, enticing her with the attractions of the city. Nelly is of an age when men are beginning to notice her, of which she is uncomfortably aware. One of those men is Jack (Stig Olin), an acquaintance of Jenny’s, and she has another admirer in the shape of Ulf (Allan Bohlin).

Crisis (Kris) was Bergman’s first feature film as director. By all accounts, including his own, Bergman had a disastrous start in the director’s chair. He might have been fired and never directed again, but the studio head, Carl Anders Dymling, an admirer of Bergman’s work, installed Victor Sjöstrom as an advisor. Born in 1879, Sjöstrom had been a very distinguished film director in the silent era, with films such as The Phantom Carriage (1921) and, in the USA, where he was billed as “Victor Seastrom”, The Wind (1928). With Sjöstrom’s help, Bergman completed the film and its production problems are not easily apparent in the finished article. Bergman regarded the then-retired Sjöstrom as his mentor, and paid him back by casting him twice in his films: To Joy (see below) and unforgettably as the lead role in Wild Strawberries.

The story is more than a little melodramatic (as it was imposed on him, Bergman described it as “grandiose drivel”), but in Bergman’s hands its quite watchable melodrama without too many directorial flourishes. Again, the strength is in the script, which gives its principal characters more depth and shading than they might have had. There’s also an emphasis on the female characters and roles, which would mark many of Bergman’s greater films, greater ones than this.

This box set now jumps forward two years, omitting two more films Bergman directed, It Rains on Our Love (Det regnar på vår kärlek, also 1946, released in the USA as The Man with The Umbrella) and A Ship Bound for India (Skepp till Indialand, 1947). Both of these were based on plays by other writers and the former’s script was cowritten by Herbert Grevenius with Bergman. It Rains on Our Love is a couple-on-the-run melodrama and A Ship Bound for India is set on a salvage vessel which gets nowhere near India (the title is metaphorical). Bergman thought the latter was his best film to date, but it was a huge flop at the box office. He also wrote Woman Without a Face (Kvinna utan ansikte, 1947), the first of three Bergman scripts to be directed by Gustav Molander – see Eva, below.

Again, Music in Darkness (Musik i mörker, first released in the UK as Night is My Future) was an assignment imposed on Bergman rather than originated by him. He was aware that he needed to make something more commercial given that his last few films had flopped. (Woman Without a Face had been a hit, but Bergman hadn’t directed that.) So this film might well have been Bergman’s last chance to prove himself as a director. Music in Darkness is based on a novel, with its author Dagmar Edqvist receiving sole script credit. Bengt (Birger Malmsten) at the start of a film is on military service. Trying to rescue a little dog from a shooting range, he is accidentally shot and is blinded as a result. Coming to terms with his disability, he lives in the country and has become an accomplished pianist. He is approached by Ingrid (Mai Zetterling) to play the organ during her father’s funeral, and so begins a romance between them, made difficult not just because of his blindness but by their different class backgrounds.

The result sounds like sentimental melodrama and it is, and Bergman hated the story. The result is certainly watchable, and it did its job by becoming a modest success at the box office, but no one would call it anything other than minor Bergman. The hero’s abilities on the keyboard does allow Bergman to indulge his great passion for classical music, of which there is quite a bit on the soundtrack. Music in Darkness had a belated UK release in 1961, one of several early Bergmans to gain distribution in the wake of his fame, but even then there was a sense that it was mainly for completists.

Bergman originally wrote Eva as a short story, but the success of Woman Without a Face led SF to look for a follow-up. So Eva became the next film written by Bergman and directed by Gustav Molander, and went into production at the same time as Port of Call, which Bergman directed but did not write.

Eva uses a three-act structure. Bo (Birger Malmsten) returns home from a stint in the Navy. He is bedevilled by guilt, from an episode from his childhood. Aged twelve, and supremely arrogant, he finds himself driving a train and causes a crash, which he survives, being thrown clear, but his passenger, a young blind girl, is killed. His lasting guilt makes difficult his romance with Eva (Eva Stiberg). A little later, Bo, with ambitions to be a jazz musician (playing the trumpet), moves to Stockholm. He lodges with husband and wife Göran (Stig Olin) and Susanne (Eva Dahlbeck). Shy and inexperienced with women, Bo finds Susanne’s flirtatiousness – even to walking around in her underwear, with her husband’s apparent consent – hard to deal with. Finally, Bo and Eva marry and move away to a remote island. She is now heavily pregnant, but the presence of a corpse washed up on the shore makes Bo wonder if there is any meaning to life and have indeed he and Eva been abandoned by God…

While Bergman did not direct this, there are clear links with his other work, both from this time and later, not least in the religious overtones that he would return to in other films.

Throughout these early films, you can see Bergman developing his style by drawing on the work of others he admired. They included Marcel Carné and in Port of Call (Hamnstad) he took several leaves out of the book of the Italian neo-realists, in particular Roberto Rossellini. However, only up to a point: he didn’t use non-professional actors and while the location scenes, in and around the Gothenberg docks, are a feature of this film, much of it was still shot in the studio.

The film begins with Berit (Nine-Christine Jönsson) attempting suicide by jumping into the water off the end of a jetty. Soon afterwards, Gösta (Bengt Eklund) meets Berit in a nightclub and they spend the night together. However, she has a troubled past, from emotionally abusive parents and time in a reform school to which she could be sent back to at any moment if she transgresses further. Gösta finds these revelations about his now-girlfriend hard to deal with, which causes him conflict as he’s aware he’s not led a blameless existence himself.

One subplot deals with an illegal abortion and its consequences. This is dealt with quite verbally (if not visually) explictly and certainly goes beyond what the American and UK censors would then have allowed. In fact, at the time, abortion was a subject the BBFC deemed not to be dealt with at all. Port of Call didn’t reach British cinemas until 1959, when it went out with an unsurprising X certificate. In fact, it’s reviewed by the Monthly Film Bulletin in the same issue (November) as Bergman’s then-new film, The Magician (Ansiktet, also known in English as The Face).

This was the first Bergman feature photographed by Gunnar Fischer, who would shoot most of Bergman’s films for the next decade or so, including Bergman’s masterpieces of the 1950s. The partnership lasted until 1960 and The Devil’s Eye, when Bergman and Fischer fell out. Bergman began his partnership with another great cinematographer, Sven Nykvist, which lasted until the end of Bergman’s cinema directing career.

Prison (Fängelse, originally released in the UK as The Devil’s Wanton) is an auspicious film in Bergman’s career as it was the first for which he wrote an original script and directed it. SF were clearly cautious as he had a much smaller budget than he would normally have had. Music in Darkness, Port of Call and Eva had all done well enough at the box office. However, Prison flopped completely. Quite what contemporary Swedish audiences made of it is anyone’s guess, but they certainly stayed away.

As a film, it’s a long way from the narratively conventional dramas that Bergman had written or directed up to now. An old man, Paul (Anders Henrikson) enters what looks like a warehouse but is actually a studio where Martin Grandé (Hasse Ekman) is shooting his new film. Paul is Martin’s old maths teacher and he pitches an idea for a film about Hell on Earth: much the same as it is now, but no nuclear weapons so that we can take the easy way out, The Devil rules human lives. The rest of the film is meant to illustrate Paul’s thesis, centring on Tomas (Birger Malmsten), Martin’s journalist brother, whose marriage to Sofi (Eva Henning) is unravelling. Tomas has interviewed Birgitta Karolina (Doris Svedlund) and becomes involved in her life and that of her pimp Peter (Stig Olin). If that wasn’t enough, Bergman uses several devices counterpointing illusion versus reality: the technical tricks of the trade of a film studio, Birgitta’s heavily symbolic dreams and a comic interlude where Birgitta and Tomas show a silent comedy film, one actually made by Bergman for the film and which makes another appearance in the prologue of Persona (which has its own share of distancing devices). The film also has, ten minutes in, credits spoken by Hasse Ekman, rather than appearing as text – a device never very common then or now, with a famous example earlier in the decade being Welles’s The Magnificent Ambersons. So the only written title is “Slut” (“The End”) at the end, though this digital restoration has a printed credit roll afterwards. (As “slut” has a different meaning in English, you wonder if there’s some unfortunate Swedish film somewhere where that end title appears over the picture of a woman. Many of Bergman’s films were released in English-speaking territories with English-language credits, perhaps for this very reason, though the dialogue remained in subtitled Swedish.)

After that step forward, another back, and a film which Bergman directed where he receives no writing credit. That goes to Herbert Grevenius (who had co-written It Rains on Our Love) who adapts stories by Birgit Tengroth, who co-stars in the film. Thirst (Törst, also known as Three Strange Loves) does still cover much the same ground as other early Bergman films. It takes further Bergman’s interest in women, with three female leads, though here from source material written by a woman.

Rut (Eva Henning) is a ballerina returning by train from a tour in Italy, with her husband Bertil (Birger Malmsten). As they travel through a Germany still bearing the scars of war she remembers her affair with Raoul (Bengt Eklund), a married soldier. This resulted in Rut becoming pregnant – the abortion, procured by Raoul, has left her unable to have children. Viola (Birgit Tengroth) is a widow with whom Bertil has had an affair and is at the mercy of a sadistic psychiatrist. Valborg (Mimi Nelson) has forsaken men altogether and turned to women, but that’s as fraught as you might imagine in post-war Sweden. (In fact, the Swedish censor demanded cuts to the scene where Valborg tries to seduce Viola by getting her drunk, material that was not seen until 2004.)

Gunnar Fischer returned as cinematographer and his mark on the film is visible through the lengthy, frequently mobile shots – long takes which show Bergman’s expertise as a stage director and giving plenty of room to his actors. So while this is one of the few films where Bergman had no writing credit – after 1950, there would just be two such cinema features (Brink of Life and The Virgin Spring, both written by Ulla Isaakson), as well as the shot-for-TV but cinema-released The Magic Flute, from Mozart’s opera – there is plenty in the film that is characteristic of him and on which he would build over the coming decade.

Bergman closed the decade with To Joy (Till glädje), his second film as director from his own original script, released in February 1950. Despite that second word of the title, there seems to be little joy in this film. It opens with Stig Ericsson (Stig Olin) returning home to find that a kerosene stove has exploded, killing his wife Marta (Maj-Britt Nilsson) and badly burning his daughter. The film then proceeds in flashback, each section introduced by a caption.

Stig is a violinist in a small provincial orchestra and gradually realising that his talent isn’t up to his hopes as a musician. Bergman, now over thirty, looked back at his teens, where his talent was evident but his maturity wasn’t. While his reputation was as a writer and director for more than one medium (film, stage, radio, later television), his first love was music. When asked, apropos Music in Darkness if he would prefer to be blind or deaf, he chose the former as he could not live without music. Therefore, in this film he transferred aspects of himself into his lead character and made him a musician. (See also the much later Autumn Sonata, in which he explored his regrets at putting his career before his wives and children, though in this case his surrogate was not a director but a concert pianist – and a woman, played by Ingrid Bergman (no relation) in her final screen role.) Playing Sönderby, the elderly conductor of the orchestra is Victor Sjöstrom, Bergman’s mentor, in one of two acting roles he played for Bergman. The film is of course named after the fourth movement of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony, which features in the closing scene.

Joining the orchestra is Marta, the only woman there, something of which Sönderby doesn’t entirely approve. She and Stig marry and have two children, which causes her to retire from music in favour of homemaking. However, Stig’s lack of progress in his own career means he takes out his frustrations on her. He has also been unfaithful. (Bergman had been married twice by then, and was never the most faithful husband, so there may be more autobiography here.) By now, Bergman was discovering the power of the small gesture and was on the way to becoming one of the screen’s greatest exponents of the close-up. One such is the scene where Sönderby remembers discovering Stig and Marta holding each other in a silent embrace. And the final sequence shows us another, as Stig, newly bereaved, plays in the orchestra the Beethoven music of the title. As the orchestra plays, Stig and Marta’s young son enters the room at sits in one of the otherwise empty audience seats, the film ending on his rapt expression.

Ingmar Bergman Volume One is a five-disc Blu-ray set from the BFI, a limited edition of 5000. The discs are encoded for Region B only. Torment and the two on-disc extras are on Disc One, with the remaining films two per disc for the next three discs and To Joy on its own on Disc Five. The set as a whole has a 15 certificate, earned by Prison (an X originally) and Thirst (first certified in 2004 for its DVD release). Crisis, Eva and To Joy had their first UK commercial releases on DVD and are respectively 12, PG and PG. Of those which did get cinema releases, Music in Darkness was cut in 1961 for an A certificate (I would guess Mai Zetterling's, or possibly her body double's, brief nude scene) under the title Night is My Future, but is now uncut at PG. Torment was cut for an A and is now a PG. Port of Call was an uncut X but is now rather leniently a PG (a certificate granted in 2004 – it would most likely get a 12 now).w).

All eight films were shot in black and white 35mm and in Academy Ratio (1.37:1). Each transfer begins with Swedish text detailing the source materials for the video and audio restorations. Each are in 2K resolution and are from an interpositive (Torment, Crisis, Prison) or duplicating negative (the others). Generally, the results are very pleasing, with blacks, whites and greys as they should be, contrast (so vital to black and white) present and correct and grain natural and filmlike. Music in Darkness looks a little softer than the others. There is some minor damage in the form of scratches and speckles, but nothing distracting.

The soundtracks are the original mono, rendered as LPCM 1.0. There’s not much to be said: all are clear and the dialogue, music and sound effects are well balanced. English subtitles are provided, but they are option if your Swedish is good enough. Some brief snatches of other languages, such as English, are not subtitled.

Bergman interview (63:07)

This took place on 7 September 1981, as part of a National Film Theatre tribute to Alf Sjöberg, who had died the previous year. Speaking in English though apologising unnecessarily for it, Bergman is interviewed by Peter Cowie (a Bergman authority and indeed his biographer). He talks about Sjöberg’s films and his own involvement with them, which includes Torment, but inevitably much of the talk turns to Bergman. For example, Cowie’s discussion of Sjöberg’s work in television leads to to Bergman’s television work and a discussion of the difference between shooting electronically and on film. There don’t appear to have been any audience questions (or they have been edited out) and there are likely to have been film extracts shown, also edited out. This item plays as an alternative audio track to Torment, and when it finishes, the film soundtrack takes over. If you have the BFI Blu-ray release of Bergman: A Year in a Life, this interview appears as an extra on that as well.

Ingmar Bergman: First Cries, Early Whispers (20:17)

A video essay by Leigh Singer which covers the films in this set, bringing up Bergman’s recurring themes as they were first expressed here, and pointing up the work of key collaborators in front of and behind the camera, particularly from this period Gunnar Fischer. Bergman’s increasing repertory company of actors is represented by clips of their work here and in later films – given that all the films in this set are black and white, occasional clips from colour films come as a visual jolt. (With the one exception of 1964’s All These Women, Bergman made every film before 1970 in black and white, and for that matter in Academy Ratio too.) This is a very useful introduction to the set, without too many spoilers, and it is hoped something similar could appear on the BFI’s three later volumes.

Book

If there is one reason why, if you have any interest in Bergman, you should make sure you get hold of this set before it sells out, is this perfect-bound book, which runs to ninety-six pages.

It begins with “A Breath of Fresh Air” by Jan Holmberg, an overview of this period in Bergman’s career. It does acknowledge that Bergman tended to be dismissive of his early films and that he is clearly learning his craft and wouldn’t make any of his acknowledged masterpieces until the next decade (and the next BFI Blu-ray box set) but concludes that “to compare Bergman with Bergman” would be unfair and that these early films have a charm and a life of their own.

This is followed by essays on each film in the set – seven essays, as one covers two films. This is “A Filmmaker Haunted by His Childhood” by Philip Kemp, which deals with the two films here directed by others, Torment and Eva, making a case for them being as much Bergman as the ones he directed, from others’ source material or not. Geoff Andrew discusses Crisis in “Directorial Beginnings”, which again makes a case for the film’s merits even if it also displays Bergman’s inexperience.

Music in Darkness may be one of the films in this set less easy to make a case for (and Bergman would have agreed) but Jessica Kiang does in “Brought to Light”. She begins with Dick Cavett’s famous flub in his 1971 interview with Bergman in which he introduced the great man as the director of among other films The Seventh Veil...a film which was made three years before Music in Darkness and which Bergman’s film has more than a few similarities to. Kiang acknowledges that this is as close to work for hire as Bergman got, other than maybe his 1953 soap commercials. Perhaps, she suggests, its relative neglect is due to its genre: the romantic melodrama, or more specifically, the “women’s picture” and that Bergman, already clearly interested in his women characters and their inner lives, has actually put Ingrid at the centre of this film instead of its nominal protagonist Bengt. She also points up the theme of blindness, often visited on the woman in such films (Magnificent Obsession, for example) but here on the man.

Philip Kemp returns, and his approach to Port of Call is summed up by his essay title, “‘In the Spirit of Rossellini’”. Bergman seems to have thought that too much of the film was shot in the studio, though Kemp is clear that visually the film is different to what had come before, specifically because of its location work – and maybe because it was Bergman’s first collaboration with Gunnar Fischer. He also points out the centrality of a woman, rather than a male Bergman surrogate, in this film, and its effectiveness is as much to her performance as anything else.

Alexandra Heller-Nicholas contributes “This is (Not) Hell: On Ingmar Bergman’s Prison”, which discusses the film as a question: do we identify with its characters and their sometimes harrowing fates, or do we acknowledge Bergman’s distancing devices, that it is actually a film and a constructed work. Kat Ellinger in “Thirst: The Story of Birgit Tengroth”, which she sees as the beginning of Bergman’s abiding interest in women and their complexities. Bergman always gave Birgit Tengroth full credit, especially for her contribution to the lesbian aspects (as a heterosexual male, he clearly felt out of his depth) and for showing him the power of a small decisive gesture, when she improvised a shot of Viola holding a lit match in front of her face. Ellinger concentrates on Tengroth in this essay, given that Tengroth has been barely discussed in film criticism other than basic facts and dates. Indeed, her contribution to Bergman’s work has been underplayed by just about everyone except Bergman himself. Interestingly, Ingrid Bergman in her early career in Sweden was often compared to Tengroth and they were rivals to some extent.

Finally, Laura Hubner looks at To Joy in “Bergman’s Ode to Experience”, looking at the film from the perspective of its protagonist, wanting to be a star but coming to understand Sönderby’s philosophy of the value of second-rateness. Also, his sometimes fraught relationship with Marta may have its roots in Bergman’s own experiences.

The book also contains full credits for each film, notes and credits for the extras, and plenty of stills.

This first of four Blu-ray box sets from the BFI covers much of the first decade of Bergman’s career both as a writer and a director before becoming a fully-fledged writer-director. It was a period of learning for Bergman, who would emerge in the next decade to worldwide acclaim. But that’s the next volume.

|