They say in Harlan County

There are no neutrals there

You'll either be a union man

Or a thug for J.H. Blair* |

| 'Which

Side Are You On?' – Florence Reese |

It's hard to explain to a crying child

Why her Daddy won't go back

So the family suffer

But it hurts me more

To hear a scab shout "Sod you, Jack" |

| 'Which

Side Are You On?' – Billy Bragg |

The

fight by mineworkers for a decent living wage, safe working

conditions and even the right to join a union has been a long and international one that has, in

its time, cost many lives and left entire communities in

ruins. The above quoted lines are from different interpretations

of a song that came to symbolise the struggle. Written by

Florence Reese in response to the brutality of the strike

in 1930s Harlan County, Kentucky, it was later adapted by

Billy Bragg as a rallying cry for the British miners' strike

in the early 1980s. The title was even used by the venerable

Ken Loach for his 1984 documentary on the same. But we'll

get to that later.

I'm

willing to bet that very few of you reading this review

have ever participated in a workplace strike, let

alone stood on a picket line and attempted to communicate

your message to those passing through the gates who have

refused the call. I'd be damned surprised if many film or

DVD reviewers have ever done so. I'd even go as far as to

speculate that not many of you are even members of a workplace

union. It's a concept that is too often consigned to history

by the children of the post-Thatcher age, where the idea

of community and unity has been traded in for a more self-centred

focus on the individual, and the wants of the one are

almost always put above the welfare of the many. The very

idea of unionisation has been and continues to be demonised

by the yellow press, and any hint that people are collectively

willing to stand up to unfair legislation prompts them to unleash a tirade

of lies and abuse that a depressing proportion of the population

seem willing to swallow. In a time when British employment

law heavily and increasingly favours the employer, the very

concept of 'power mad unions', as they are so often dubbed

by the tabloid right, is simply ridiculous. The message

sent down by the powers that be to those working at the

lower end of the economic pyramid is clear – accept your

lot and don't complain about it, and if you try to improve it

in any way then we will do everything in our power to stop

you. And we have a lot of power.

And

people accept it. That's the worst aspect, the thing

that makes the struggle for fair and equitable treatment

such a slog. A sizeable proportion of those who chose not to join

a workplace union do so because they have grown up with the

media-fed misconception of what unions are about. But just

as many simply cannot comprehend, or just do not believe

in, the concept of collective action. They buy into the company

PR that assures them that fairness and equality is a workplace guarantee,

that if they play by the rules then their employer will always do

right by them. When it does go wrong, as it too often does,

their illusions are suddenly shattered and they don't know

where to turn. I see this a lot where I work. As a workplace

union representative, the single most common phone call

I get starts with the words "I'm not in the union,

but..." These are people who suddenly find they need the

organisation they were never before willing to commit a

few pounds a month to be part of and support, despite being happy to reap

the benefits that the men and women who went before them had fought and paid

for. Only when they find themselves in trouble are they suddenly

and urgently interested in becomeing a union member. It's like being

in a road accident and afterwards asking an insurance company

if you can retrospectively cover your car and make a monetary claim.

It

is perhaps a testament to the democratic nature of the internet

that a film about industrial conflict can be written about

by someone who at least has experience of strikes and picket

lines, rather than just academics who have merely read about

it or seen it on TV. Many years ago I lost a job, in part

because I tried to organise the workers at a small factory

into a collective voice (the pay and conditions were atrocious),

and as a union steward of many years standing I have taken

part in my share of industrial action. The decision was

never taken lightly or without good reason, even though

the media has sometimes done its best to trivialise the

cause or misrepresent the issues. And the mere fact that

we were on strike at all was often seen as evidence of our

inherent evil. According to them, if we exercise our only

real bargaining tool and collectively elect to withdraw

our labour, for whatever reason, we are doing so out of

selfishness. This is bullshit. And as the rights of workers both here and in the USA are gradually

eroded, it's dangerous bullshit.

I've

stood on and organised picket lines and dealt with everything

from indifference to verbal abuse, but I'll freely admit

that I've never had a gun pointed at me or faced off a gang

of strike breakers armed with baseball bats. I've also never

stood on that picket line for almost 10 months while my

family attempts to make do on a paltry strike fund in lieu

of wages. Would I fight that hard and long on a matter of

principle with the hope of bettering my lot? I really don't

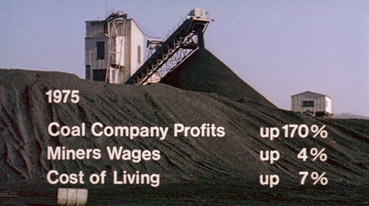

know. But if I were a miner back in 1973, living in run-down company shacks with no internal plumbing and working in

conditions that were resulting in long term illness

and premature death, you're damned right I would. Such was

the struggle of the Harlan County miners and their families.

What were they fighting for? Nothing extravagant or unreasonable,

just the right to join the union of their choice, the United

Mine Workers of America.

The

mining companies of Harlan County in Kentucky had a long

history of fighting the unionisation of their workers. In

the late 1930s, a series of bitter conflicts between the

miners and their employers ended in an armed battle and

several deaths. In the dispute at the centre of Harlan County USA, the representatives of the Duke Power

Company and its subsidiary the East Mining Company claim

that it is not the principal of a contract with the UMWA

that they are opposed to, no sir. All they want is for the workers to sign a 'no strike' clause, effectively robbing

them of their only bargaining tool. On the surface, then, it may seem as if the men were on strike to win the right

to go on strike, but it was about much more than that –

it was about a decent living wage, about safe working conditions,

about having proper sanitation and plumbing in the

only housing they could afford.

Barbara

Kopple was prepping a documentary on the Miners for Democracy

reform movement when the Harlan Country strike began, and

she, in her own words, "just jumped into it, not knowing

what to expect." Initially blanked by a wall of distrust

from a community that was inherently suspicious of outsiders,

a combination of determination and chance soon saw that

wall begin to crumble. She lived with the miners, stood on the picket

lines with them, even took cover with them when they were

being shot at by gun thugs. And she did this not for a couple

of weeks, but for ten months. In the process she became

part of the very community she was documenting, and as a

result got far closer to her subjects and their plight than

her outsider status would normally have enabled.

Initially

a chronicle of the strike itself, the film sidetracks to

provide some historical background on the 'Bloody Harlan'

strike of the 1930s, the 1969 murder of union activist Joseph

Yablonski and his family (ordered by corrupt union president

Tony Boyle, whom Yablonski opposed), and the damaging effects

of the disease known as 'black lung', the result of years

of inhaling coal dust in poorly ventilated mines.

But at the film's humanist core are the miners and their

wives. A formidable force in their own right, the women

– notably the indomitable Lois Scott – prove to be every

bit as determined and possibly even more organised than

their men folk. Their collective strength of character is

vividly communicated as they draw up rotas for picket duty,

harass the local sheriff into serving an arrest warrant

that they have procured, and in one of the film's most memorably

tense scenes, face down a group of gun thugs with sticks

and baseball bats.

Kopple's

total commitment to the miners' cause will no doubt create

problems for those still clinging on to the misguided belief

that all documentaries should sit on the fence in a vain

attempt at balance. This is especially inappropriate in

the case of political documentaries, who purpose is often

to fly in the face of popular understanding, to present

a view that contradicts the often establishment-sanctioned

status quo. In many cases it is this oppositional viewpoint

that goes some way to providing the very balance the complainers

are looking for – you want the opposing opinion as well,

then just open a paper, switch on the TV or just turn open your ears in a public place.

You'll find it everywhere. And although the politics of

the situation are crucial to the story being told here,

the film is primarily about the miners, their families, and how they

are affected – their lives, their suffering, their

determination, and above all their complete dedication to

their cause. And Kopple's integration into the community connects

us with it's citizens to such a degree that we begin to

enjoy their company as much as she did, and to better understand

and sympathise with their struggle.

In some respects, the mining families fit the role of classic

movie underdogs, fighting for justice in the face of impossible

odds for a cause that any reasonable audience can rally

for. They are likeable, articulate and passionate, their

battle is just, and the odds are heavily and increasingly stacked

against them, with an injunction served to stop more than

a handful protesting at one time, but a blind eye turned

to the weapons fired at them by the company gun thugs. The

film even has an identifiable bad guy in the shape of Basil

(pronounced "Bay-zil") Collins, a genuinely unpleasant

and sometimes frightening figure who appears prepared

to use any means at his disposal against the miners and

their families. But the stakes here are far higher than

in any fictional feature precisely because what we are watching

is real. Thus when a group of thugs armed with bats approach

the picket line there is the worrying prospect that we will

witness someone we have come to know and like being horribly injured, and when the increasingly

frustrated miners find themselves in a firearms stand-off

with Collins and his goons, the possibility that it will

result in on-camera death is almost stomach churning. This

is most vividly realised when the violence is directed at

Kopple and her two-person crew, a sudden and aggressive

assault that is immediately preceded, in the film's most famous

and terrifying moment, by a shot of Collins pointing his

gun directly at the camera as a young visiting lawyer screams

off-camera for him not to shoot. Eventually our worst fears

are realised, but it is the aftermath rather than the incident

itself that proves the most sobering, and becomes the sad catalyst

for the reaching of an agreement between the employers and

their workers.

The

film tells its story in rivetting fashion and shines in its subjects and a whole string of memorable moments and scenes,

not all of which are as dark as those detailed above. Kopple's

ability to repeatedly surprise or delight us can be

found in the most unexpected events, from Lois cheerfully

pulling a revolver from her dress to an absolute gem of

an exchange between a New York beat cop and mineworker Jerry

Johnson, who is in town to protest outside the New York offices

of the Duke Power Company at their annual shareholders'

meeting. Such intimate moments are the direct result of

the long-term commitment of Kopple and her colleagues, her

willingness to devote over a year of her life to a project

that she never believed would be seen by anyone but her family and friends and those she was filming. It is the sort

of film that just could never have been made by an organisation,

the funding required to send a paid crew into the mining community for that length

of time being beyond the means of most documentary budgets, and

the subject matter alone would be unlikely to attract a

commission. This is documentary made with passion, dedication and a belief in what you are doing that extends way beyond

the film-school desire for recognition as a filmmaker. That

this recognition came to Kopple anyway in the form of widespread

cinema distribution, an Academy Award, and the film's inclusion

in the National Film Registry of the Library of Congress

in 1990, is a kind of pleasing, poetic justice.

Harlan

County USA remains one of the great documentary

works of the modern age, and politically is as relevant

now as it ever was. Miners in America continue to fight

for justice (Utah 2005 – see the Sundance supplement on

this very DVD) and unionised workers across the developed

world are finding themselves in the worrying position of fighting

not just for better rights and conditions, but to prevent

the gradual erosion of those that our predecessors fought

so hard and in some cases gave their lives for. Meanwhile

non-unionised labour in areas from fast food restaurants

to supermarkets continue to be exploited by organisations

whose annual turnovers exceed that of some small countries.

It

would be heartening to think that the film would also inspire

up and coming filmmakers to point their cameras with an

eye for the message rather than the audience or the pay

cheque. That said, getting the resulting film seen and the

achievement recognised is, in the UK at least, a struggle

in itself – witness Franny Armstrong's three year devotion

to the McLibel

trial and the long fight to get the film the TV screening

it deserved (her extraordinary Drowned

Out has still yet to seen on UK TV), while the above

mentioned Ken Loach documentary on the UK miners' strike,

Which Side Are You On?, was initially banned by the very people who commissioned it for showing the striking miners in a sympathetic light.

If

I seem to have gone on a bit then it's only because it's

hard to stop talking about something you love. Harlan

County USA is a marvellous example of the political

documentary at its best, combining politics and humanism

with the immediacy of Direct Cinema and the drama of the

finest of fictional features. And it's all real, every frame. If you're suffering under the weight of a workplace struggle

of your own, then see it for inspiration. If you are dismissive

of the need for unions then see it to understand the necessity

to organise and fight for what you believe is right. And

if your job pays a good wage and the working conditions

are beyond reproach, then see it to appreciate the sacrifices

made by previous generations of workers to make it so, and

fight tooth and nail to prevent those hard-won rights being

taken away from you.

Shot on 16mm, the footage itself was framed 1.33:1, but matted to 1.78:1

for the New York Film Festival screening and the more widespread

release that followed, and that is the version included

here. This does mean that some of

the framing is uncomfortably tight, and the odd chin or

head is cropped, but for the most part this aspect ratio works

well. Given

the inherent grain issues with high speed 16mm stock at

the time (film stocks have come a long way since), the transfer

here is remarkable. The grain is still evident, but is never

intrusive and not enhanced in the manner of many inferior

16mm-to-digital transfers. The level of detail is very good,

the colour natural without evidence of unnecessary enhancement,

and the contrast feels about right, and this can be a difficult

call given the range of lighting conditions in which the

film was shot. Most surprising is the level of clarity to

the night-shot footage – grain is heightened and colour

information reduced, but for the first time on any home

video format I could clearly see what was going on. There

is some softness of picture in places, but given the sometimes

restricted lighting and film format this is inevitable,

and does not detract in any way. Once again, Criterion have

done the film proud. The transfer is anamorphically enhanced.

The

Dolby 1.0 mono soundtrack is true to the original and needs

no remix, despite the extensive use of the folk songs of

the coalfields, particularly the work of Hazel Dickens.

The restrictions imposed by the locations occasionally make

themselves known (camera noise can be heard in a couple of

the interviews, for example), but on the whole, the dialogue

and music demonstrate an unexpectedly level of clarity and

fidelity. Top marks again.

Given

special edition status by Criterion, the included extras

here more than justify that oft-misused label.

First

up there is a commentary by producer-director

Barbara Kopple and supervising editor Nancy Baker. This

does not appear to be screen specific exactly, and sounds

more like a couple of recorded interviews with the pair

that have been edited to match the on-screen action. Either

way this is a fascinating track, loaded with information

on the production and its participants, as well as some

intriguing post-production stories. Kopple regards the film

as the most important of her career and the making the film

as a political act, and sees the miners' wives as genuine

role models. This is great stuff – informative and entertaining,

it's an essential companion to the film.

The

Making of 'Harlan County USA' (21:43)

is a retrospective documentary on the production made specifically

for this DVD, and includes interviews with a number of those

involved in its production. A lot of ground is covered and the

variety is engaging – Kopple talks about the film, the people

and friendships, while coal miner Jerry Johnson remarks

that they warmed to the young filmmakers in part because

they looked poorer than those in te mkining community. There is some minor

overlap with the commentary, but the addition of facial

expression and gesture freshens the stories. There is some

useful expansion on the technical information, and clarification

on just how close one stand-off came to all-out slaughter.

Six

Outtakes (26:17) are in their

original 4:3 ratio and sometimes awash with dust and scratches,

although these have been treated to reduce their prominence

and the picture quality is otherwise admirable for what

is essentially 'rescued' footage. All six are fascinating

for different reasons, but my favourite sees Lois defending

the local sheriff for his open support of their cause and

lambasting those who sit on the fence and won't take sides

in the fight.

The

Hazel Dickens Interview (11:43)

puts a face to the coal miner's daughter who provided some

of the key songs for soundtrack. She talks about her early

life, her start in music and reveals that she likes playing

to a political audience. "Some of us," she says,

"have to stand up and do what you believe in."

Absolutely.

John

Sayles on the Film (6:27) has one of America's

most determinedly independent directors talking about the

importance and effectiveness of Harlan County USA,

including its influence on his later (and superb) Matewan,

which chronicled the 1920 Matewan miners' strike and subsequent

massacre. He also reveals that he generally prefers a good

documentary to a dramatic feature.

Harlan

County USA at Sundance (14:02) is a panel

discussion held at the 2005 Sundance Film Festival, where

the film received a 30th anniversary screening. Hosted by

a passionate Roger Ebert and featuring Kopple and cameraman

Hart Perry, the floor is also given over briefly to two

striking Utah miners (one talks in Spanish, which is subtitled),

whose case provides evidence that the struggle is far from

over. Kopple is clearly as passionate as ever.

The

trailer (3:02) is in very good

condition, considering its age. It's a good piece that sells

the film really well.

Finally

there is a 22-page booklet containing

and insightful essay on the film by Paul Arthur, and an

equally interesting one on the music by music journalist

Jon Weisberger.

It's

heartening to see how just how good Harlan County

USA still is – its message is as relevant as it

ever was, and much of it feels surprisingly contemporary

in style and structure. This is in no small part thanks

of its influence on later documentary and even feature and

television work, from the aforementioned Matewan

and the TV movie Harlan County War (about

the 'bloody Harlan' strike of the 1930s), to the stylistic

urgency of Homicide: Life on the Street,

three episodes of which Kopple directed.** The film receives

exemplary treatment on Criterion's DVD, and should be considered

a must-have for documentary enthusiasts and politically

active film lovers everywhere.

|