|

"We

will drown, but we will not move."

When

I reviewed Marc Singer's superb Dark

Days a couple of years back (the

review was re-posted to this site in December 2003), I

challenged anyone to name ten documentaries they had seen

at the cinema the previous year, knowing full well that

few living outside of a major metropolitan area would be able to do so.

In the time since that film did its limited rounds, the

international runaway success of Michael Moore's Bowling

for Columbine has prompted (or perhaps coincided with) a renewed public interest in the documentary feature,

and in the past few months alone we have seen UK cinema

releases, complete with sizeable press coverage, for Capturing the Friedmans, The

Fog of War, Fahrenheit 9/11 and a good few others.

All of which is good news – after years of marginalisation,

documentary features are being widely discussed alongside

their mainstream dramatic counterpart.

There

is a sneaking suspicion, though, that this new-found enthusiasm

by established distributors for releasing documentary

material in cinemas and on special edition DVDs comes less

from excitement about the content than the combination

of Bowling's commercial muscle and the

marketable badge of Oscar or Cannes wins and nominations.

It's also worth noting that each of the above listed films is American

in origin and deals with American issues. Take a wander

outside the English speaking world and tackle

a subject that's not in the news at the time of release

and you'll still struggle to attract a major distributor or even production funding. As a result, getting your film seen by an audience of any significant

size becomes something of a problem, and if your documentary was shot

on DV on a budget too small to calculate and you're dealing

with a political issue that isn't considered 'sexy', then God help

you. Which, frankly, is bloody tragic, as there is some

excellent and important work being done at this level

that demands to be seen but has to be literally hunted

out. In the past year we have seen, amongst others, Leila

Sansour's compelling Jeremy Hardy vs. the Israeli

Army and Chris Reeves' eye-opening look at the Iraq war from an angle few will have seen before, Human

Shields in Iraq. And now we have, courtesy of

the independent production company Spanner Films, the

remarkable Drowned Out.

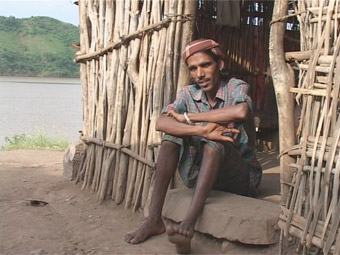

A

little background. The Indian government has embarked

on one of the most ambitious dam-building projects in

recent memory, funded by a loan from the World Bank. To

the people of the drought-ravaged Northern districts

this could mean water and electricity, but to the indigenous inhabitants

of Jalsindhi – people known as Avidasis, whose

village is due to be submerged by the construction of

the giant Narmada Dam – it represents an end to a way of

life that has existed for generations. As protests against

the dam-building become more widespread and the government's

promises of relocation and water distribution are called

into question, the villagers decide they would rather

drown in their homes than move from their ancestral land.

Increasingly, of late, documentary features have been successfully competing

with their dramatic counterparts by employing many of

their cinematic techniques, whether it be the stylistics

of Errol Morris (The

Thin Blue Line, A Brief

History of Time), the humour, pace and

confrontational tactics of Michael Moore (Bowling

for Columbine, Fahrenheit 9/11)

or the thriller pacing of Kevin McDonald (One

Day in September, Touching

the Void). Often this sees them beating the dramatic features from whom they have borrowed at their own game. But this latest

work from Franny Armstrong – the young director of the inspiring McLibel:

Two Worlds Collide (1997), which

both the BBC and Channel 4 have shamefully bottled out

of showing – is having none of it. This is a documentary

of the old school, told at an unhurried pace and using interviews,

a sober voice-over and illustrative graphics, and employing not

a hint of cinematic trickery to seduce those with an MTV

attention span. What the film does have, and what makes

it such a compelling and persuasive work, is a subject

very worthy of everyone's attention and response, and

a deceptively straightforward but beautifully developed

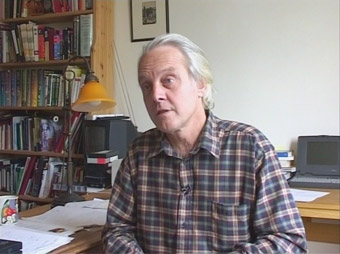

structure that mirrors World Bank investigator Dr. Hugh

Brody's description of how his team discovered the full

extent of the problems behind the Narmada dam project:

"There wasn't a moment of revelation," he says

"it was much more the peeling an onion." He

may well have been describing Armstrong's film, which

employs this very approach, as fact after fact is revealed

to ultimately devastating effect.

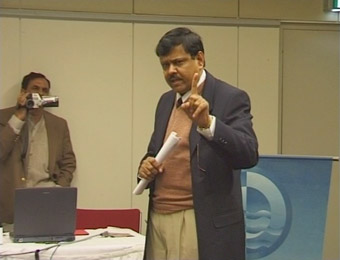

Given

the synopsis supplied with the film and our familiarity

with the Take No Prisoners approach of Michael Moore,

John Pilger and others (whose work I do greatly admire,

I should point out), Armstrong's method is initially a

little disarming in being so even-handed, leaving

you unsure just where your sympathies should lie. The opening

scenes quickly establish that the Jalsindhi villagers'

self-sufficient way of life is to be turned upside-down

by the construction of the dam and we are left in no

doubt of the wrongness of this move. But having done this, Armstrong

then introduces us to enthusiastic dam engineer Ashok

Ghjjar and the initially reasonable-sounding Irrigation

Minister Jay Narayan Vyas, and takes us to a

village in the drought-ravaged northern region of Gujarat,

whose groundwater level is dropping at the alarming rate

of over a metre a year, a situation that the diverted

water from the dam is intended to alleviate, and our sympathies

can't help but shift. Though we still care for the plight

of the Jalsindhi villagers, we can't help but wonder that

if a few have to be resettled in order to benefit

millions for whom water is a luxury, is this not a price

worth paying?

Except,

of course, it's not that simple. As the film progresses

and more details emerge, it becomes clear that this reasonable-sounding

reading of the situation is in fact the very one being

promoted by the Indian government. And they are not telling

the whole story, not by a long shot. As the questions

start to pile up, the answers offered prove increasingly

unsatisfactory. It turns out that we're not talking about

a handful of villagers, but 25,000 people from 162 villages (a staggering 16

million people have been displaced over the entire course

of the Big Dam project), and investigations by the World

Bank – who only got involved again because

of the repeated protestations of Booker Prize-winning

author Arundhati Roy, the tireless determination of protest

group founder Medha Patkay, and a very public hunger strike

– suggest that the project is technically flawed in a

number of ways and that it is unlikely that any of the

water can be effectively transported to those most in

need. The simple fact of the matter is that it just won't travel that far. It will, however,

make it to the 'Golden Corridor' industrial belt that

sits handily en route, where companies are already erecting

huge plants to make full use of this new water supply.

It becomes clear that the Jalsindhi villagers are having

their homes and livelihoods sacrificed not for others

like them, a decision that would be morally questionable

in itself, but for the needs and greed of big business

and a government it appears to have in its pocket. Sound

familiar? It should.

Having

lived and successfully farmed their ancestral land for

twelve generations (one village elder effortlessly recounts

his family history back that far), the villagers know

and want no other way of life. The government promises

relocation, but when their spokesman, the affable and

hugely likeable Luhariya, is taken to see two of the proposed

resettlement sites, he encounters land that has either

been already allocated to others or is impossible to effectively

irrigate due to a salt-heavy or polluted water supply.

The inhabitants of many other villages are not offered

land at all, just a cash settlement that will last only

a few weeks in whatever new location they may end up,

usually an overcrowded city slum. And this is just the

start. As we increasingly connect with Luhariya, his

family and his fellow villagers, their determination to

drown with their property rather than relocate becomes

one we can genuinely empathise with – who in their right

mind would want to exchange a simple but in many ways

idyllic existence for a life of misery, disease and unemployment

on the very bottom rung of an overpopulated industrial

society? But to the Jalsindhi people it is more than that

– they have been self-sufficient farmers for countless

years and this is not about a lifestyle change, but simple

survival. By the time you get to this DVD's extra features and

hear Luhariya's wife Bulgi say "The government

won't allow us to die – and yet they won't give us land

to live," you have a clear understanding of just

what she means.

One

of Drowned Out's many and considerable

strengths is that it packs an extraordinary wallop without

ever becoming overly dogmatic. The matter-of-fact narration

and the calm, thoughtful interviews most effectively build

an unanswerable case that has rightly prompted widespread

public outrage in India but has effectively gone unnoticed

elsewhere. No-one is crudely demonised, and Minister Vyas

continues to churn out reasonable-sounding argument, but

the emerging facts give his words an increasingly hollow

ring. When he talks of being happy to relocate if

it were he that was asked to move – "gladly, willingly,

smilingly" – at the same time giving us a guided

tour of his opulent city establishment, you are left wondering

if he is even living on the same planet as the villagers.

Occasionally Armstrong uses familiar techniques to give

weight to the film's argument – footage of a peaceful

demonstration cuts to one that ended in violence that

actually occurred some years earlier – but she is always

up front about this, with information about what happened

and when supplied through caption and voice-over, even

if the emotional connection prompted by their close association

remains. Music, too, is used to emotive effect, but is

done so with subtlety and you never feel you are being

clumsily manipulated.

Drowned

Out is a gripping, persuasive documentary for all the right

reasons, highlighting a terrible injustice that has ramifications

for the whole of modern Indian society and, ultimately,

governments everywhere and their relationship with big

business. In one of the DVD's extra features, a member

of one of the displaced families says to Armstrong, "People

like you come and take photos and then go away. What good

does that do us?" If the film in question – and that's this film – remains unseen then he makes a good point, which is precisely why you should hunt it

out at all costs and urge others to do likewise. This

is gripping, meaningful and moving cinema that is the

result of dedication and commitment rather than the committee-meeting

approach that makes so many modern TV documentaries and

dramatic feature films so facile, and should be seen by

everyone who cares even a hoot about their fellow human

beings.

Shot

on DV-CAM (on the low budget film-maker's favourite, the

Sony PD-150) in a variety of lighting conditions, the

video aesthetic is wholly appropriate to the film itself,

and is generally well transferred to DVD. Occasional picture

softness is slight and very likely the result of filming

conditions at the time. On the whole the contrast and

sharpness are very good, and artefacting is only really

evident in darker scenes, but that's something you have

to live with when shooting on DV with no lights.

Flashy

5.1 soundtracks rarely have a place in documentary works

(a recent exception being Touching

the Void), the Dolby 2.0 track here

does what it says on the tin, so to speak, and does it well.

Clearly mixed and crystal clear throughout, it, like the

visuals, belies the no-budget production status. The diegetic

sound and narration are essentially front and centre weighted,

the music score is spread more widely across the front sound

stage.

With many distributors seemingly in competition to see

who can have the least number of extra features and still

call their disk a Special Edition (for the record, Tartan's

'Collector's Edition' re-issue of The Eye gets my vote for simply having a DTS track instead of

the original Dolby 2.0 one), this independently produced

and distributed disk of a not widely seen documentary

puts most of them to shame. Not only does it have a terrific

selection of high quality extras, it also presents them

with a wit and intelligence that the major distributors

should damned well learn from.

Though

unheard of in the early days of DVD, commentaries on documentaries

are starting to become a little more common. Given the

unpredictable nature of documentary production, where

events are often unfolding as the film is being made,

interviews rarely go as expected, access to locations

and key people can be restricted in a variety of ways,

and the story itself will sometimes not even start to

take shape until the film is in post-production, I always

welcome any background information provided by the film-makers.

The commentary here is hosted

by director Franny Armstrong, and includes contributions

from several of the technical staff, including the composer

Chris Brierly, narrator Nina

Wadia, sound engineer Neil Hipkiss, songwriter Frank

Hutson, and Franny's sister Boo (really), who was instrumental

in getting footage out of the country when Franny and

the protesting villagers were arrested. The key contributor, though, has to be Jalsindhi

village spokesman Luhariya, who speaks through an interpreter

and comments on how he feels the film has portrayed their

story and sometimes directly reacts to events and people

on screen. On the whole this is a very informative and

involving track that provides plenty of background information

on the film's zero-budget production, balanced nicely

by Luhariya's more personal thoughts on matters unfolding.

Occasionally, the commentary is slightly out of sync with

what is being discussed on screen, but this is no doubt

due to editing in order to most effectively use all of

the contributions. It should be mentioned that, typical

of this DVD, the technical aspects of the track are first

rate, with no dead spots at all and very clear sound,

despite, as Franny informs us, it being recorded at a

friend's house (compare this to the technically shabby

commentary on the Clerks DVD), and in

a brilliant move that every DVD with a commentary track

should immediately employ, the disk uses one of the available

subtitle tracks to introduce on screen each contributor

and their role in the film.

Next

up is a follow-up featurette, What Happened

Next (14 mins). I say next up but it should

be first up as, in one of several really nice touches,

you are automatically taken to the intro screen of this

extra once the main feature has finished, the assumption

(rightly in my case) being that this is the first thing

you will want to check out when you have finished your

initial viewing of the film. It is the first of five 'mini

features' that can be accessed via a sub-menu in the extras

section. Shot in the summer of 2003, two years after the

main filming was complete, much of this footage was for

a new ending for a 45 minute version of the film called The Damned that was was broadcast in the US last

year. It is to Spanner Films' credit that they kept this

as an extra rather than re-edit the feature to include

it – I do like to see films as they were originally shown

rather than how they have been 'revised' later on. Running

14 minutes and framed 4:3 (as are all of the extras),

this adds a sobering postscript to the film and brings

the story up to date, giving further details of the continued

progress on the dam and its dramatic effect of what little

remains of the Jalsindhi farmland.

Cinema

Jalsindhi (13 mins) is a video diary following Franny Armstrong

and small crew as they return to the village with generator

and projection gear in order to show the finished film

to those who appeared in it. Armstrong herself, with her

everso English accent and cheery self-confidence, comes

across initially as a very familiar figure to anyone working

in the film industry, but soon emerges as way more down-to-earth

and committed than most of the rather self-important ner-do-wells

I seem to have encountered over the years, and her dedication

to the project really comes across here (as if spending

three years on a budgetless film for no pay didn't). Just

getting to the screening proves a problem in itself, and

the water levels they encounter on the way add a little

personal experience to the story of the dam and its consequences.

It's a fascinating extra with some very nice touches –

the home-made electrical plug being a favourite – and

its really good to see the crew interacting with the people

they filmed, something those outside a production rarely

get to witness.

Passing

Us By (2 mins) is a brief but informative and affecting update

from the Renital lake slums in Jabalpur. It is here that

one interviewee makes the aforementioned comment regarding

people who take pictures and leave. I'm glad that was

left in, as any documentary film-maker must – or should

– consider that very point every time they go off to make

a film.

Small

Solutions (7 mins) looks at the concept of check dams, a localised

way of trapping water that can effectively make many villagers

self sufficient. It plays like an appeal for funding –

which to a degree it is – complete with promotional video

music and a mixture of interview, graphics and positive

cut-aways, but is nonetheless enlightening, and certainly

puts its case convincingly. This links nicely to...

A

Miracle Growth (3 mins) is a simple appeal for funds to help villagers

to be self sufficient, showing how a small irrigation

pump can make all the difference to their way of life.

It is followed by a title page giving details of how you

can help. Worked for me.

The

next section, Photos and Myth,

has three sub-menus. Karen's Photos contains

14 images shot in Jalsindhi by freelance photographer

Karen Robinson in August 1999. The images themselves are

good, but as so often with DVD-included photos are framed

smaller than full screen size, so you'll have to use your

zoom control or shuffle forward a bit to get a good look.

Production

Photos is a 2 minute montage-with-music of production photos

from the film, many of which can also be found on Spanner

Films' website and again suffer from downsizing, though the quality is

otherwise first rate.

Adivasi

Creation Myth is a 2 minute 30 second video extra in which Luhariya

explains, accompanied by images of the villagers at work

and play, the Adivasis creation story.

The

third section, Offcuts, leads

to a sub-menu containing interview material with key contributors

to the film that did not make it to the final cut, including

one with author Patrick McCully whose contribution

to the film was dropped for structural reasons. The lengths

range from 6 to 11 minutes and are all very useful and

sometimes fascination inclusions, especially the animated

McCully, whose contribution is referred to intriguingly

in the commentary.

Also

included here is a 2 minute 45 second Deleted

Scene showing a demonstration led by Medha

Patkar in London against Siemens, who were planning to

invest in one of the Narmada dams. This appears to have

a few digital motion glitches but is otherwise an interesting

inclusion that shows the extraordinary Patkar in full

flow, and contains a telling moment that could almost

be representative of outside attitudes to these issues,

when a security guard tells the demonstrators flatly:

"I don't really care what's happening in the Third

World. There are people campaigning about everything in

this world." This simply but effectively illustrates

the problems facing those trying to highlight these issues

in the West, including, of course, the film-makers.

The

next section is a Quiz, whose

purpose is to highlight some of the negative effects of

the dam construction on the Jalsindhi villagers. Done

as a series of 20 multiple choice questions (you can make

your selection using the remote control), the answers

provide yet more information on the Jalsindhi inhabitants

and their plight. If you paid attention to the film you

should be able to score top marks on this, but you'll

still learn something new, and there is a nice undercurrent

of political sarcasm in places: One of the selectable

answers for "According to the government, why are

250,000 people being forced to sacrifice their homes and

livelihoods?" is "To show them who's boss."

Indeed.

The

final section, Spanner Films,

has further sub-sections. Franny Armstrong is

a rather casual – cosy even – 20 minute conversation with

the director. It does provide a useful level of background

information on Armstrong and the production, including

the advantages she had going into the film production

process – her father runs his own production company,

for example, and a friend had become a multi-millionaire

– but also her level of political commitment and lack

of interest in the financial rewards of film-making, two

rather ideal qualities for a fledgling documentary film-maker

with a conscience. Includes extracts from McLibel and Drowned Out and some footage in Franny's

home/office/editing suite, which is a lot tidier than

mine.

The

Making of Drowned Out is a textual reproduction of the article by Franny Armstrong

that appeared in The Guardian in August 2002.

Filmography is just that, but includes a 3 minute trailer for McLibel.

Credits lists the credits for the film and the DVD. Selecting

individual names gives more information, and in a feature

I have not seen before and got rather hooked on, all of

those involved are connected by a small caption under

their photo. For example, under assistant producer Will

Ross's picture you have "Ex-boyfriend of..."

– select that and you are taken to Franny Armstrong's

biography, and a further caption appears that links you

to the next member of the crew. This does tend to emphasise

the small-scale family feel of the production company,

and is a very nice touch.

Drowned

Out is an unflashy but compellingly made documentary

on a subject that demands attention. It works both as

an investigation of a local issue and as an examination

of the too often shady relationship between governments

and big business in general. As so often, in this story

it is the poor that are being made to suffer for the benefit

of the industrial rich, a message that is delivered here

without overstated polemic, but with intelligence, skill

and humanity.

The

DVD is, frankly, the most complete I have ever seen for

a documentary feature, loaded with extras, all of which

are of a high quality and all of which contribute to the

story, the characters and the message of the film – there's

not a superfluous special feature in the whole, succulent

bunch.

Astonishingly,

given that that this is one of the best documentaries

I have seen in a long while and one of the most polished

DVD releases of the year, you can't just nip down to Woolworth

and buy a copy – a truly independent production, this

(unless you live in London) can only be bought directly

from Spanner Films via their web site at www.spannerfilms.net,

priced £20, plus postage. This compares well with

major releases (if bought in shops rather than discounted

on-line) and every copy sold helps go towards funding

future Spanner Films projects.

At

a time when politically committed documentaries are as

rare as hens teeth on UK TV, it is heartening to come

across such a beast on such a well specified DVD. Hunt

it out, spread the word, and when, in a few years time,

Franny Armstrong is being discussed as one of the key

documentary film-makers of our generation, you can say

you were in there at the start.

|