| Démanty Noci/Diamonds of the Night is available as a stand-alone DVD from Second Run and has also been released as part of a three-film box set titled The Czechoslovak New Wave: A Collection, which also includes Ivan Passers's Intimni osvetleni / Intimate Lightning and Juraj Herz's Spalovač mrtvol/The Cremator, which have been reviewed separately. |

"In spite of everything, I still believe that people are really good at heart." |

| Anne Frank |

A picture, they say, paints a thousand words. Czechoslovakian director Jan Němec's debut feature Démanty noci/Diamonds of the Night, a founding film of the Czech New Wave, exemplifies that oft-cited proverb to a tee. During its runtime of just sixty-four minutes, you might expect the filmic equivalent of a haiku or perhaps a Shakespearian sonnet. Instead, Diamonds has a word count that Tolstoy would be proud of. Nothing, and I mean nothing, is wasted. Every second of film and every image printed upon it is overflowing with meaning, bursting to the brim with emotional resonance.

Němec's unique, dazzling and compelling work already has something of an advantage in that regard from the start, since Diamonds is a Holocaust story. Did a chill come over you then? Did you feel an immediate sense of dread and unease? Did newsreels and other film footage spring up in your mind? So much can come from that potent little word, articulating our global horror and shame in three syllables. Its legacy and its imagery are burned into our consciousness, and burned deep, so it's not that difficult a task to elicit untold amounts of sympathy (and more than a few tears) from an audience when you explore the period in any medium, not just film.

If you're feeling a little nervous at this point, then you can be forgiven. Fiction films which deal with this material tend to vary wildly in quality and approach, whether sensationalised (and some would argue trivialised) as with the famed NBC late 1970s miniseries Holocaust, personalised as with Steven Spielberg's Schindler's List or the many adaptations of The Diary of Anne Frank, or works which are more morally ambiguous such as Stephen Daldry's The Reader Mark Herman's The Boy in the Striped Pyjamas. Before you ponder how Němec's film tackles things, there's nothing remotely overwrought, trivial or over sentimental here. I can say with complete and utter honesty that it's the most original, assured and unconventional film you'll ever see. This is film about the essence of survival, which strips things down to the purest of forms, which allows it to engage with the audience using a language beyond the spoken word, allowing us to enter the minds of the protagonists, to experience their memories, dreams and nightmares at first hand.

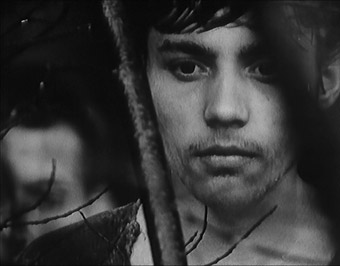

Diamonds of the Night tells the story – though it seems rather strange to be discussing this film with such conventional terminology, since the 'rules' of filmmaking aren't really applicable here – of two young boys, who escape from a train bound for a Nazi death camp. The first (Ladislav Jánsky) a thin, tall boy, carries an injury, hobbling along at first with the aid of a stick and later, gripping tight to his friend's shoulder, and in the worst moments, when the boys need to give chase, dragged along by the scruff of his shirt. The second (Antonín Kumbera), is younger, dark-haired (his dark soulful eyes are magnetic and draw you in from the start), fitter, his only complaint to begin with is the cold. He's the centre of this world, and with whom we spend most time.

We follow their journey as they try to put distance between themselves and their captors. By day, they progress, slowly, tired, hungry and increasingly desperate through woodlands and rocky crops, quenching their thirst in streams. By night, their sleep is fitful, sheltering from view and the cold. All the while, they're on edge, on alert, ears pricked up for the slightest sound. Time stretches out, so we're not sure which hour of the day it is, and the line between reality and fantasy soon blurs as we enter one of the second boy's mind reliving parts of the escape, his childhood, and sometimes his imaginings of what the future may hold, beyond the horizon he and his friend walk toward.

Diamonds covers similar themes to Němec's FAMU (Prague's Film and TV School of the Academy of Performing Arts) graduation film Sousta/A Loaf of Bread, which is based upon the experiences of writer Arnošt Lustig during the Holocaust. For his first feature-length film, Němec would again use Lustig's work as source material. This time working with him to bring his novella, Tma nemá/Darkness Casts No Shadow, itself inspired by Lustig's escape from a Dachau-bound train. However, this is no ordinary, straightforward literary adaptation either. Where the usual modus operandi for scripts of this type is to cram in lots of detail (sometimes to the detriment of the story), Němec strips things right back, as if he's taken Lustig's book through a filtering process to leave behind something that is visually quite stark, but it's far from emotionally cold. If anything, it's a more potent experience, simply because we come to the film with so much pre-existing knowledge, and a great deal more than Němec's contemporary audience of 1964 (though thanks to the limited run and the Czechoslovakian authorities that number was relatively small).

Anyone lacking in that knowledge won't find it here. Diamonds is not a history lesson.

There are few markers of the period, save for the jackets the boys wear emblazoned with KL (for Konzentration Lager/Concentration Camp) whilst their fellow prisoners wear the more well-known striped uniforms. The Jewish-originated forenames Lustig gave his protagonists, Manny and Danny, are also removed, so subsequent press notes and reviews refer to them by number, itself perhaps a nod to the experience of concentration camp life or the mere fact the these boys and their plight stand for many for like them, lending the film a universality, transcending the boundaries of country and religion. Němec too subscribed to this wider theory, specifically choosing actors who were not Jewish for the roles. The last casualty of Němec's distilling is dialogue. Heavily present in Lustig's novel, where the boys share memories and stories with each other along the way, Němec's boys are almost always silent. The first line of dialogue comes thirteen minutes in, and the first conversation proper comes a few moments later.

Given all these alterations, you would expect that Lustig may have been displeased with Němec's rather brutal approach to his material, but it remains the writer's favourite adaptation of his work, and it's easy to see why. Far from being dull and oversimplified, Diamonds is a visually and aurally dense work, and depicts those dark Holocaust years in a manner that's uniquely subjective and deeply personal, in a different way to documentaries and eye-witness testimony. For all intents and purposes, we become the eye witness to the story, learning the shape of the narrative as it goes along. Sometimes, it feels like we are the third escapee, thanks to cinematographer Mirsolav Ondříček's handheld camera work. At times, our closeness to them is almost unbearable.

There's so little to be interpreted in the way of spoken language that it's probable you could view this film without subtitles. However, the same can't be said for the film's soundtrack. Ostensibly about memory and the relationship between the past, present and future, Diamonds is also a sensory film, full of sound and texture, mimicking the real physiological triggers for memory. The contrast of black and white, where black is ink dark and white is dazzlingly bright – eerily reminiscent of, though prefiguring the news footage of the camps that would immerge some twenty years after this film's release – works particularly well, and makes us sensitive to any form of change in that balance. When the film becomes so dark, we lose the boys completely, the only relief comes in the form of the undergrowth continuing to bend and snap as they carry on walking.

You come to fear silence quickly.

What we hear on screen therefore becomes just as important as what we see, and is almost another character. While at FAMU, one of Němec's many influences was Robert Bresson, and can be seen or rather heard throughout the film. The soundscape, though realistic, feels heightened by the situation. Every gunshot and every snap of a twig or branch seems inordinately loud, and places us on edge from the opening moments. The fact we the very first sound we hear in this film is a tolling bell gives things an eerie, unsettling quality, and that unease just grows, when the next sound is a gunshot, followed by a German-accent plea to 'halt.'

If it's not already abundantly clear, this is a film which steers rather than shies away from convention. One of the most startling, and at first confusing aspects of Diamonds is its use of flash-cuts, in an echoing one of the French New Wave's most famous memory films, Alain Resnais' Hiroshima mon amour/Hiroshima my love, a director whom Němec cites as a key influence, exposed to his work during his days at FAMU. However, don't disregard any of the experimentalist techniques Němec uses in the film as mere copycatting; they do, as everything else in the film, serve a very real purpose. By their very nature – breaking into the drudgery of the boys travels, flashing up like shards of glass – they make us sit up and take notice, wondering where these moments might be from or where they may lead us to.

As the film progresses, the fragments do begin to make more sense, as we've become conditioned to their presence, so learn to expect them, but they also last longer; acting as a representation of the boy's need to retreat from their surroundings into a place they find comfort. Of course, there are flash-cut sequences that are less idyllic in nature, teetering on the ever-shifting boundary between real and surreal, dream and nightmare. The most surrealist moments occur when the boys are at their worst, possibly a reflection of the delirium they must be feeling (expressed by the second boy's often inappropriate bursts of laughter), and is the most obvious homage to another of Němec's cinematic influences, Luis Buñuel. In one particularly striking sequence, where the boys attempt to cross over some rocks, the second boy slows to a stop, exhausted, and we see his foot, hand and then his face covered in ants, obviously a nod to the infamous eyeball cutting sequence in Un chien andalou/An Andalusian Dog and it's just as disturbing. It stands out here as the culmination of the artistic and the emotional, as a particularly visceral trick of the mind. The boy's relief when he brushes his face to find the insects have disappeared is palpable.

Such tricks aren't just for the boys though, they're set up for us too. The construction of the film means we naturally question things and search for answers, but as the narrative progresses, we begin to question what we're seeing as well as why we're seeing it. This is taken to a new degree when Němec presents and then re-presents the same events, slightly altering their outcome. In doing so, we're left wondering which events were imagined and which events were real, showing rather neatly how our fallible our memory can become over time, flagging up the incredibly complex relationship all human beings have with perception and the differences between what we remember, what we imagine, and what wish to forget.

In many ways, Diamonds of the Night is a love letter to cinema, describing all it can achieve and all it can inspire. Sometimes, there are few words big enough to describe just how beautiful the picture being painted before our eyes actually is, but I can muster one that comes close: unforgettable.

Framed in its original 1.33:1, the quality of the image is not quite up to those on recent Second Run DVD releases, but this this appears to be largely down to the condition of the source material rather than any transfer issues. The contrast in particular varies depending on the lighting conditions, being solid in daylight but greying out when it gets dark, though this was clearly necessary to retain picture information that would have been lost had the contrast been boosted. When the detail is good it's very good – a scene involving a shooting party is very crisp and well balanced – and despite the odd scratch there are almost no dust spots to be seen. There is some burn-out on the whites in some shots and the picture does look a little enhanced at times. Grain is visible throughout, but is very much part of the aesthetic of the film.

Given the film's age, it's hardly surprising that the mono 2.0 soundtrack is a little restricted in range.

If the draw of Němec's film and the prestige of it being a DVD premiere to the English-speaking world (doesn't that have a lovely ring?) aren't enough for you – though really, it should be – then read on. As ever, this is a well-packaged and beautifully presented release, with digitally restored image and sound, alongside improved Czech subtitles (optional). Beyond the film itself, there are a small but perfectly formed set of extras to take a look at. Quality and Second Run now go hand-in-hand for me, and Diamonds is no exception.

Diamonds of the Night: An Appreciation by Peter Hames (20:22)

I wasn't at all surprised to find Peter Hames on this disc, since he's contributed to so many Second Run releases in the past (including Daisies and Valley of the Bees) and it was great to put a face to the name. This might just be my nerdy film student showing through here, but quite frankly, I could listen to Peter Hames talk all day. Filmed in his book-lined office, this is a treat for anyone who loves to hear well-formed discussion on a film and/or a director, and Hames' passion for his subject comes through in no uncertain terms. The wealth of knowledge he imparts in such a short space of time is impressive, covering the landscape of the Czech New Wave in a broader sense, before dealing with Němec's life, work, and uniquely personal filmmaking style in more detail. Throughout, the focus is of course placed upon Diamonds of the Night, underpinning much of the discussion, and often used as reference point for the rest of Němec's output.

Hames' appraisal of the film and the director is poles apart from the rousing, philosophical speech-like take on Pedro Costa's Blood delivered by the late João Bénard da Costa, but it's no less effective. It works as a great introduction to both, but be warned that it does give away elements of the plot, so it's probably best left until after your initial viewing if you're unaware of the film or Němec completely. When you do watch, you'll come away from it feeling like you've genuinely learned something, and the title of the featurette is apt, because you'll have new appreciation for Diamonds of the Night and the talents of Jan Němec too.

Picture Gallery

A collection of over twenty stills, navigable by using the 'back' and 'next' options on the screen. Lovely in their own right, they highlight what a beautifully composed film Diamonds of the Night is.

Booklet

I've come to anticipate the contents of these now, and I wasn't disappointed. Illustrated with some lovely stills the material is roughly a 50/50 split between an article on Diamonds of the Night, written by Michael Brooke (curator of Screenonline at the BFI National Archive and a frequent contributor to Sight and Sound magazine), and a biography of Němec.

As a fan of Brooke's writing, this was a particularly nice read, since it's one of those pieces that sounds as if you're the one being spoken to, as if you and Brooke are sat somewhere chatting over the film, albeit a incredibly in-depth one. That style is an apt choice for the work of Němec, since he deals with human beings and their stories in the purest fashion, and Brooke's article works in much the same way. Rather than being preaching in a dry superior manner – a commonality to most academic writing – it's entirely without pretence, written in, dare I say, a friendly tone. However, don't let my description fool you, that's not to say that this a throwaway inferior piece, actually, it's quite the opposite; full to bursting with details in the form of plot, stylistic and thematic analyses. Brooke's appreciation for the film and its director are abundantly clear. Lovely stuff.

The biography is written with just as much care, and packs in great deal, switching between the basic facts and figures to consider various films in turn to a fair level of detail, discussing how the director and his career both have fared over the years. A nice change from your average biographical piece.

Beyond the quality of the articles themselves, I was pleased to see some extra notes for further reading on Czech cinema and Jan Němec's work, as well as places to seek out the director's other features. A particularly nice touch.

Diamonds of the Night is an extraordinary debut, and an intense experience that showcases completely the unique skill of its director Jan Němec. Honest, pure, and with a dark beauty all of its own. This is a deceptively simple, but incredibly complex tragic story that will stay with you for days. In it's depiction of the triumph of will in the bleakest of situations; Diamonds of the Night is also a triumph for cinema. A genuine rarity, the like of which you will probably never see again. Unmissable.

|