|

If you’re of a certain age, you may remember the Children’s Film Foundation (CFF) as the source of part of Saturday morning picture shows at your local cinema in the days before multiplexes, with plenty of noisy boys and girls left there for the duration by their parents. I don’t have such memories, partly because my local cinema wasn’t in the town I lived in, but a bus ride away. However, if you watched Screen Test on Fridays on BBC1 (several presenters, but the one in my time was Michael Rodd) you would often seen an extract from a CFF film, and your observation would be tested immediately afterwards. I mention these details not just for nostalgic reasons, but because the clear market for a box set like this is nostalgic adults. Present-day children may find them less appealing and may indeed wonder if some of these films have been misplaced from the Ark, and not just because five out of the nine are in black and white.

Children’s matinee showings date back to 1927, where in the course of a morning you could see Disney cartoons, B westerns and episodes of serials like the three Flash Gordons made in the 1930s...anything as long as it was wholesome and would keep an audience of youngsters entertained. Cinema owners wanted British films to show to British children, with British moral lessons to impart, as many American films shown were thought overly violent, frightening or generally unsuitable. And so the Children’s Film Department was formed, which in 1947 became the Children’s Film Unit. However, it closed down and was replaced in 1951 by the CFF which was the basis of the organisation which still exists today: later, the Children’s Film and Television Foundation and, as of 2012, the Children’s Media Foundation. The CFF was funded by the Eady levy, which took a proportion of cinema ticket prices. Films were made by independent production companies on behalf of the CFF, who maintained the rights to the films. The films made were standalone features which typically ran from fifty-five minutes to just over an hour, some serials, some short films and some magazines (compilations of short documentary items aimed to appeal to the young audiences).

The CFF continued to make films into the mid-1980s, when the Eady levy was abolished. The BFI has made use of its archive holdings to put out several CFF compilations on DVD, and this is their third “Bumper Box” of nine films plus extras. As I say above, I suspect the audience for this set is not the one the films were originally made for, and there is a tendency which this release doesn’t avoid to treat them in mainly kitsch terms. Undoubtedly many of these films show their age in the language used and in social attitudes, and as such are time capsules for an era that is no longer ours. The casts, often made up of stage-school children sporting RP accents, can seem rather dominated by the middle classes and not really reflecting the Britain that existed then, let alone now – but that’s something adult films and television didn’t always address much at the time either. Threat and danger is dialled down to U-certificate levels, though some films are now PG, partly due to behaviour now more regarded as dangerous. (Don’t get into a car with strangers, children.)

On the other hand, the CFF was a testing ground for filmmakers and actors who went on to other things. Or alternatively they finished their careers there: Michael Powell’s final fiction film, The Boy Who Turned Yellow, was made for the CFF.

| THE CLUE OF THE MISSING APE |

|

Sea cadet Jimmy (Roy Savage) rescues a pilot from a burning crashed plane. As a reward, he is given a visit to Gibraltar. However, he and Pilar (Nati Banda), his host’s daughter, discover a plot to blow up the Fleet, led by Gobo (George Cole).

Despite the title, apes don’t feature particularly much in this film, which was set and shot in Gibraltar. In fact, as the film points out, they’re monkeys. Admittedly part of the plot is an attempt to poison them. Director James Hill makes the most of the overseas locations, not to mention the assistance from the military, and gets good performances from the two young leads. The story devolves into a long chase, with the adults – of course – less quick on the uptake than the children.

| ADVENTURE IN THE HOPFIELDS |

|

Left alone when all the other families in her street go on a hop-picking holiday, Jenny (Mandy Miller) accidentally breaks her mother’s china dog. In a panic, she hurries off and just about makes the train from London to Kent, hoping to earn enough money to replace the broken dog. However, her letter home to her parents gets lost, and they call the police...

This film is an early credit for director John Guillermin (1925-2015), who had begun his cinema career after his War service and went on to a forty-year career, often specialising in big-budget action fare. Adventure in the Hopfields is on a necessarily smaller scale, but it shows his ability to work with actors, in particular one of the major child stars of its time. Mandy Miller (born 1944) first appeared in films at the age of six and had made a considerable impression in the title role of Mandy in 1952. Her acting career only lasted six more years, ending with the effective Hammer thriller The Snorkel.

It’s interesting to see that a film aimed at children of both sexes could feature a female lead without making any fuss about it, when the prevailing wisdom is that girls will watch films about boys and identify with the lead characters, but the opposite won’t happen. So more often you get films with boy/girl ensembles, or simply only boys, and there are examples of both in this set. Yet Mandy Miller, aged nine at the time of shooting, holds the screen effortlessly. The film does skirt around some aspects – are the children often seen with dirty faces (led by a young Melvyn Hayes) meant to be what would then be called gypsies? The film doesn’t spell that out. Jane Asher and Anthony Valentine can be glimpsed among the children and familiar names such as Mona Washbourne and Dandy Nichols among the adults. Much of the film takes place in a genuine hop-picking camp and some of the extras are no doubt real hop-pickers.

There’s a story that this film was considered lost until a copy was found in a rubbish tip in Chicago in 2002. However, that’s contradicted by the BFI’s collections database, which has held copies at least as far back as 1988. The opening title card has the words “Revised Version of 1972”, from when the film was reissued in that year. (Presumably early-Seventies children had no objection to black and white, given that most of them would not have had colour television sets yet. Even if they did, black and white films could still be shown in prime time throughout much of the decade) The difference is a brief voiceover by adult Jenny at the start and an opening caption of “London 1953”, making the film a period piece rather than the contemporary one it originally was.

Following that, Tim Driscoll’s Donkey is a gentle animal story, of one boy and his donkey, set and filmed mostly in Ireland. Young Tim (David Coote) lives with his grandfather Mike (John Kelly). His favourite animal is a donkey, Patchy, which he has reared from a foal. However, a combination of circumstances means that Patchy is mistakenly sold as part of a batch for export, and Tim sets out to get him back…

Tim Driscoll’s Donkey shows signs of patches (sorry) in post-production: a voiceover narration holding the story together and some awkward edits presumably to get round some of the younger castmembers’ inexperience. The action ends up with Tim riding Patchy in a race at a donkey derby, one clearly shot to get round the fact that the donkey playing Patchy clearly isn’t moving very fast. The film is undoubtedly one from an earlier, gentler age – it’s a pleasant watch, but underwhelming.

We jump forward a decade, though still in black and white, and a film which at the time was a little topical, given Dr Beeching’s closures of many railway stations only a few years earlier. This is certainly one for train fans as Runaway Railway features a steam locomotive specially restored for the production. It was filmed on a military railway line in Hampshire and Bordon (not “Borden” as it is misspelled in the booklet, or at least is in the PDF copy received for review) Station becomes the fictional Barming Station. This time we have an ensemble of children – Charlie (John Moulder-Brown, who will make another appearance in this set quite soon), Arthur (Kevin Bennett), John (Leonard Brockwill) and Carol (Roberta Tovey) – foiling two comedy crooks, Mr Jones (Sidney Tafler) and Mr Galore (Ronnie Barker) in their bid to rob a mail train. Director Jan Darnley-Smith (who helmed quite a few CFF productions) even throws in a brief band performance on the station platform. Though the villains are more farcical than threatening, Runaway Railway shows that to make a successful children’s film you don’t at any point talk down to your audience, and the result is highly entertaining.

Calamity the Cow shows that the CFF was still making films in black and white in 1967, a year when the number of new monochrome films for adults, in the English language from major studios at least, had dropped to single figures, and would drop to just one the following year. (Inadmissible Evidence, from the John Osborne play, in case you were wondering, though it didn’t see its British release until 1969.) John Moulder-Brown turns up again, and the oldest and tallest of the children in the film is one Phil (billed as Philip) Collins, in his previous career as a child actor. He and the director did not see eye to eye, which caused his character to be written out of the story partway through. As the CFF was based in Elstree, many of their films were shot in the Home Counties and there’s not a regional accent to be heard. The film is a Surrey-set cattle-rustling story, with Calamity (again an animal raised from undistinguished calfhood) being stolen and the children joining forces not just to get her back, but to enter her in the local agricultural show. This is mostly played for farce, with a notable contraption put together from and old bath and parts of a bedstead to transport our bovine star. Agreeable stuff.

A year later, and now we are in colour, late-60s bright saturated colour at that. Tony (Anthony Kemp) is given to tall stories, but when he accidentally comes across a plot to kidnap the Prime Minister on a visit to the town, who believes him? He and his friends Mary (Mary Burleigh) and Martin (Martin Beaumont) set out to thwart the plot. Chief villain is Stella, Judy Cornwell clearly having a great time in her late-Sixties gear. The villains are played straight rather than for laughs, which helps. There are a lot of well-known names in small roles: Ian Hendry, Janet Munro (then married to Hendry, in her last screen role) and Wilfrid (spelled here as Wilfred) Brambell taking care of the comedy scenes as a hapless delivery man on a bike. Cry Wolf is an entertaining hour and one of the best in this set.

On to 1979, and the CFF cashes in on the big-trucks and CB-radio trend, following Sam Peckinpah’s 1978 film Convoy, itself derived from C.W. McCall’s 1975 hit single of the same title. Big Wheels and Sailor are the names of the trucks driven by Mike Harvey (Nigel Humphries) and Dave Adams (Julian Curry) with their children, a daughter and son each. However a gang of criminals, led by “Mother” (Sheila Reid, overdoing the villainy) aim to hijack the trucks. The results are amiable enough, but fairly forgettable.

David (Simon Nash) and his younger brother Stephen (John Hasler) are birdwatching in the woods when they witness a getaway car being supplied to two escaped convicts, Donny (David Jackson) and Keith (Ian Bartholomew). The two boys are discovered and Donny and Keith hold them hostage as they go in search of buried loot, with the police in pursuit…

Variations of this basic plot have recurred through many of CFF’s films, but Ranald Graham’s script and Frank Godwin’s direction give it more shading than you might expect. Something of a bond develops between crooks and captors. David Jackson, best known as Gan in Blake’s Seven, gives a sensitive performance when, given his hulking size and bald head (with tattoo), he could simply have been written and played as a thug. One scene, where it’s possible that Donny has been killed, is unexpectedly poignant.

By the early 1980s, cinema audiences were dwindling, so the funding from the Eady levy was diminishing with it. The BBC began to show several CFF productions and the CFF became the CFTVF (Children’s Film and Television Foundation), with the films from then on to be guaranteed a television showing after their cinema run. The original primary audience, Saturday morning picture shows, were also in decline. The Eady levy was abolished in 1985 and so the run of CFF/CFTVF productions came to an end. Exploits at West Poley was one of the last productions, and it’s a sign of straitened circumstances that it was shot in 16mm rather than the usual 35mm. That said, it’s an unusual excursion into historical drama. It would have been blown up to 35mm for cinema showings, but they were few and far between (there’s no review in the Monthly Film Bulletin), so some reference sources mistakenly refer to it as a TV movie.

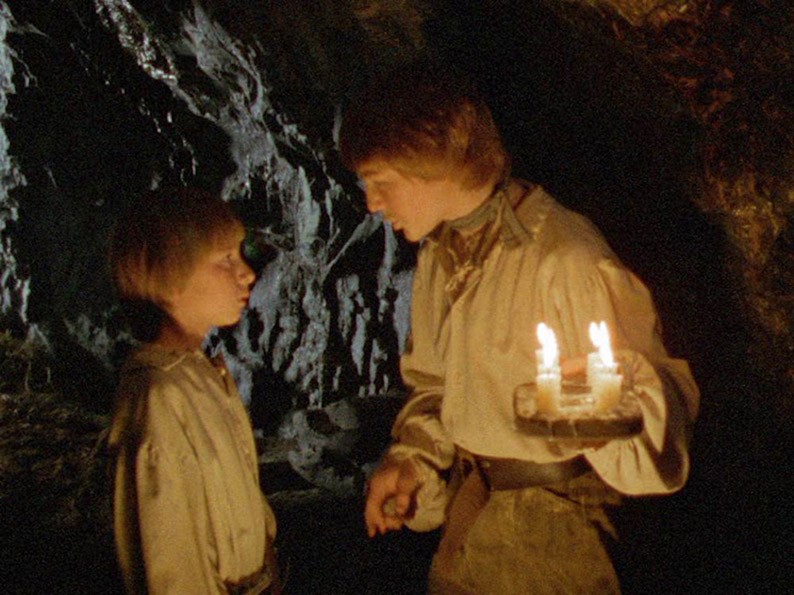

Thomas Hardy’s “Our Exploits at West Poley”, “a story for boys”, was written in 1883 but not published until 1892. (The film’s credits call it a novel, but novella is more accurate.) Leonard (Charlie Condou) is staying with the family of his cousin Stephen (Jonathan Jackson) in the Dorset village of West Poley. The two boys discover an underground cave with a fast-flowing river. In order to cross, they divert the river...with the result that West Poley’s river has dried up and a new one has appeared in neighbouring East Poley. Leonard and Stephen try to put this right, putting themselves in danger.

Exploits in West Poley does have something of the feel of a BBC classic serial, admittedly one a single hour long instead of multiple half-hour parts, and it’s a little more gently paced than other films in this set. Brenda Fricker (before Casualty, before her Oscar for My Left Foot) plays Stephen’s mother and there is an early role for Sean Bean as “Scarred Man”. This was in fact the CFF’s second go at Hardy’s novella: they had previously adapted it in 1953 as The Secret Cave.

The BFI’s release of Children’s Film Foundation Bumper Box Vol. 3 comprises three PAL-format DVDs, each encoded for all regions. The running times to the right are those on the disc: each film will have lost a couple of minutes to speed-up, as they have been transferred at twenty-five frames per second (PAL video speed) but were shot at twenty-four fps (cinema sound speed).

Every single film in the set carried a U certificate on original release: in many cases, you can see the original certificate at the start of the transfer. However, more recently, some of them are now rated PG, namely The Clue of the Missing Ape, Adventure in the Hopfields, Calamity the Cow, Cry Wolf, Breakout and Exploits at West Poley. That said, there’s very little that would disturb even the youngest child, but as I say above I suspect they’re not the primary audience for this DVD set.

Every film on this set is presented in 1.33:1. While that does look correct for The Clue of the Missing Ape (and undoubtedly is for Our Magazine No. 2) I’m doubtful that it is for the other films in this set. By mid 1953, cinemas were converting from the old Academy Ratio (actually 1.37:1) to various widescreen ratios and that was already underway in major West End cinemas at least. (Some of the early widescreen presentations were cropped showings of films which had been composed for Academy, but let that pass.) Certainly within a year or so, pretty much every new British production not in Scope might be shot open-matte (exposing the whole frame, which after all would be seen on television, then 4:3) but would be composed for a wider ratio, which was most likely 1.75:1 or 1.66:1 or maybe the new American standard of 1.85:1. (It’s doubtful that these films had much if any play outside the UK, but they weren’t intended to.) Giveaways include much space over character’s heads in any shot which isn’t a tight close-up, and brief and almost imperceptible tilts of the camera to keep someone in frame, which would not have been necessary if the film was intended to be seen in Academy. This is visible as early as Adventure in the Hopfields (shot in 1953 and released in 1954). While it may well have been the case that cinemas took some time to convert to widescreen, that had happened by the mid to late 1950s and certainly by the 1960s most cinemas could no longer show Academy unless they were repertory screens or arthouses.

As for the transfers themselves, the booklet advises that they have been mastered from the “best available materials” but doesn’t specify what they were. Some of the films are in better shape than others. Clue of the Missing Ape is soft and has some splices and damage. On the other hand, Adventure in the Hopfields looks very good and in fact exists in HD, as it’s also an extra on Indicator’s Blu-ray of Town on Trial. In some cases, it looks like cinema prints have been used, with results that are rather too dark and contrasty: Big Wheels and Sailor and Breakout are examples of this.

The soundtracks are all mono, which is how they were heard originally, rendered as Dolby Digital 2.0. There’s nothing untoward here: dialogue is clear, and sound effects and music are well balanced. It is regrettable though that there are no English subtitles provided for the hard-of-hearing (on the review checkdiscs at least), as I imagine many people would be watching these films for nostalgic reasons and would therefore be older.

Our Magazine Volume 2 (9:58)

On Disc One. This was Saturday morning’s children’s equivalent of a newsreel and in a mere ten minutes crams in items intended to appeal to that audience. So, in 1952, we visit the London Fields Primary School Percussion Band, learn how to make models with all sorts of items to hand that you might not expect, drop by the hot springs of Rotorua, New Zealand, and finally go to the British Railways Locomotive Testing Station in Rugby, though it’s only the boys who get to see the inside of the train driver’s cab – sign of the times.

Watch Out! (17:12)

The CFF’s feature presentations were typically short, three- or maybe four-reelers, but they made single-reel shorts too. This example, from 1953, also on Disc One, is one of three shorts in this set starring Peter Butterworth. Here he plays Dickie Duffell, who pays a visit to the Multi-Dimensional Film Corporation (actually Nettlefold Studios in Walton-on-Thames). Butterworth is clearly channeling the silent comedians, and there’s little dialogue but a lot of slapstick, and we do get to see behind the scenes of one of the minor studios of the time.

That’s an Order (17:10)

Playground Express (15:56)

Two more Butterworth shorts, both made by the same company in 1954 in Brighton and directed by John Irwin. Although the main character doesn’t have a name this time, they follow much of the formula of Watch Out! In That’s an Order, Butterworth is left in charge of a shop, while in Playground Express he’s equally haplessly looking after the seafront rides.

Before Its Time: The Battle for Billy’s Pond (12:26)

On Disc Three, this is a curious item, a making-of featurette for a film which isn’t actually included in the set. Along with plenty of clips from the film – and quite a few spoilers, but it ends with pointing you to the BFI’s first Bumper Box if you want to know how The Battle for Billy’s Pond ends – there are interviews with director Harley Cokeliss, Professor Robert Shail and three contemporary youngsters, Lillia Langley, Rudy Allen and Katherine Taylor who find it hard to credit that a film with such overt environmental themes could have been made as long ago as 1976.

Booklet

With the first pressing only, the BFI’s booklet runs to thirty-two pages and is almost entirely written by the discs’ producer Vic Pratt. He begins with an overview piece whose title, “Corking Retro Cinema Crackers for Kids of All Ages”, sets the tone for what follows. It’s very tongue-in-cheek and more than a little kitsch, and compounds my sense that actual children are unlikely to be watching these discs, assuming they still watch discs in any case. This piece gives a quick overview of the CFF’s history. After that, Pratt writes notes for all the films in the set, including the extras, and full credits are given. Finally, Trevona Thomson asks ten questions to see if we have been paying attention, which will take any Seventies kid right back to sitting in front of their television set when Screen Test came on – assuming you lived in a BBC rather than an ITV household, that is. (We were Team BBC, to use an expression not current at the time.)

The best CFF productions are pacy and still entertaining, though if dated they are in such a way to become time capsules of their era. This third BFI Bumper Box Set has plenty to appeal, even if more likely to nostalgic adults rather than their offspring.

|