|

This is the fifth DVD box set of Children’s Film Foundation productions released by the BFI, and I have previously reviewed Volumes 3 and 4 for this site. You know the drill: nine features (mostly between fifty minutes and an hour) from the 1940s to the 1980s, with a sampling of shorts and documentaries which might have made up a typical Saturday morning at the pictures. And if age or circumstances meant that you didn’t travel out (or were driven) to your local Odeon or ABC at the beginning of a weekend, you may well have seen extracts from CFF productions on television programmes like Screen Test.

Children’s film matinees dated back to the 1920s but much of what was on offer came from America and there were concerns that they were not especially suitable for British youth. First there was the Children’s Film Department, then the Children’s Film Unit, and then in 1951 the CFF. Later, in recognition of the medium many of its films (and latterly video-shot productions) were headed for, it became the Children’s Film and Television Foundation. In the mid-1980s, it was put to rest by a combination of the abolition of the Eady Levy (which allocated part of ticket sales to British production), the rise of home video and also of Saturday morning television – Multi-Coloured Swap Shop or Tiswas, depending on whether you were a BBC or ITV household. In its existence, the CFF (or rather the many companies making films for them) gave opportunities to many an up-and-coming young thespian, and some distinguished filmmakers cut their teeth on them. Some other distinguished filmmakers made CFF films later in their careers.

So, let’s take our popcorn and Kia-Ora – other fruit-based sugary beverages are available – and sit down in the one-and-nines (if in pre-decimal days) for this Saturday’s attractions.

The earliest film in this set dates from 1947, so early that it doesn’t have the familiar CFF fountain-and-flight-of birds ident at the start. We’re in a vanished black and white post-War world where people still drive horsedrawn carts down the high street, though a motorbike is pressed into service later on. Based on a novel by Mary Cathcart Borer, a prolific contributor to the CFF either as screenwriter or as here story provider, we follow young Roger Henderson (Anthony Wager) who returns with his father (Murray Matheson) from Egypt. However, a valuable Rembrandt in the family vault has been stolen. Roger and his friend John Wilson (Ivor Bowyer) decide to investigate. But why has Mr Henderson been called away by a fake call from Scotland Yard? And what’s up with the new housekeeper Mrs Matthews (Thelma Rea)?

Later CFFs often took care to include both boys and girls in their ensemble casts, conscious that both sexes would be watching. In fact, the opening credits of this film specifically says that it was made “for cinema clubs for boys and girls”. On a smaller scale, a film with a male lead might have a female co-lead, or vice versa. On the other hand, films like The Secret Tunnel went with the prevailing wisdom that girls would watch films about boys but not the other way round. Anyone labouring under the stereotype that CFF Land was populated by middle-class stage school kids speaking in RP accents (and here wearing jackets and ties) will find little to disabuse them. But it’s well-made, spiritedly performed and good clean fun. I suspect many contemporary youngsters mind think this film has been displaced from the Ark, but as ever I suspect they’re not the primary audience for DVD releases like this.

The writer/producer and director team of Peter Rogers and Gerald Thomas (respectively) will go down in history for the Carry On films, but they certainly made other things as well. This was Thomas’s first film as director, in 1956, two years before Carry On Sergeant kicked off their long-lasting franchise. Rogers had been in business for a few years by then: The Dog and the Diamonds, from 1953, was a CFF film which kicked off the fourth of the BFI’s Bumper Boxes and was directed by Gerald’s older brother Ralph (father of producer Jeremy). In fact, much of the humour here is reminiscent of the Carry Ons except for the smut.

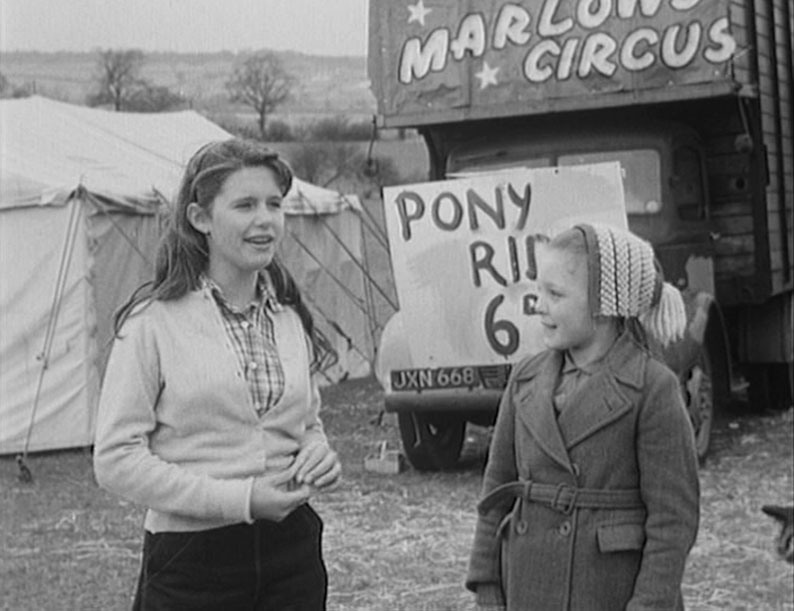

Marlow’s Circus, set up in the fields owned by Farmer Beasley (Meredith Edwards) has certainly seen better days. Bert Marlow (John Horsley) has to give the performing pony Pinto to Beasley in lieu of rent, much to the distress of Nan (Carole White, who later found fame without the E in her given name) and Nicky (Alan Coleshill). They are determined to buy Pinto back. It’s very broad stuff, with the villains broadcasting their villainy a mile off, and much emphasis given to the animals, the other being an Alsatian called Judy. Plenty of slapstick too.

The Piper’s Tune is one of the more ambitious CFF productions, being a historical story specifically set in Napoleonic times, as an opening voiceover tells us. The route for escapees is over the mountains and the network is based at a farm owned by Martinez (Charles Rolfe). A group of children are held hostage by a French platoon as they try to discover this route.

An involving story with quite a bit of action, this is helped no end by location work shot at Cregennan, Snowdonia. There’s another famous name involved here: Muriel Box, who was becoming and remains to this day Britain’s most prolific female film director. Another distinguished name is behind the camera, Prague-born Otto Heller, who had been in the UK from the 1940s. Box clearly recognised who was the particularly talented one among her young cast: eight-year-old Roberta Tovey, later to be best known as Susan in the two big-screen Doctor Who adventures later in the 1960s. She gets most of the best lines, including the final ones of the film, and a good few close-ups as well.

This item from 1963 has one of the more low-stakes premises out there. A group of children are playing with a model airplane which catches the wind...and goes inside a high tower, which is locked. How are they going to retrieve it? Drawing heavily from silent comedy, The Rescue Squad takes that premise and runs with it, taking in several setpieces involving a rope, two ladders, a washing line and a box with legs. Plus Neddy the donkey, brought in early as a literally asinine Chekhov’s gun. There’s a missing cat too.

The ensemble is a little larger than usual, with the children of various ages comprising four boys and two girls, the older and slightly tomboyish one in trousers and the younger one in a dress. Among the adults is Peter Butterworth, in what is and will be far from his first appearance on these CFF releases. Another reappearance is Mary Cathcart Borer, here with a middle initial rather than a middle name, as writer of the story (treatment). Cinematographer John McGlashan went on to a long career at the BBC, including several of the 1970s Ghost Stories for Christmas. Inventive stuff.

After all those rural or semi-rural stories, one for the many urban kids out there, even if the ones on screen do live by a river conveniently close to central London. A prank gets three children locked inside a branch of British Home Stores. Their attempts to escape lead them to the construction works on the roof where they find a gang attempting to break in to the bank next door. Their efforts to get a rise from young Trudy (Trudy Moors), who had been forbidden to play with them, were the cause of their being trapped, but it’s Trudy who comes to the rescue.

While some of the CFF’s films counted as thrillers, as often as not the characters were as black and white as the film stock. But sometimes they did play it straight, while keeping within the bounds of a (then) U certificate, which required a reassuring outcome. So it is with Daylight Robbery. Director Michael Truman makes good use of its contemporary architecture and keeps up sufficient tension, with some of the methods of deterring the thieves only verging on slapstick towards the end. The adult cast includes such names as Janet Munro, Norman Rossington and, as a policeman there to provide a message to the young audience, Gordon Jackson. There’s a score from jazz and electronic music specialist Tristram Cary.

Black and white cinematography declined through the 1960s, in commercially-intended films at least, and the CFF was no different. The death knell for big-screen monochrome was the arrival of colour television in the UK and Europe in 1967, at which point black and white films dropped in value for sales to the small screen. The CFF made films in black and white at least as far as 1967 (see Calamity the Cow, from the third Bumper Box), but colour was inevitable and All at Sea, from 1969, is one such example. Throw in location shooting in Spain, Portugal and Tangier to make the most of those multifarious Eastmancolour hues. But it’s not a travelogue, as the plot involves smuggling and the efforts of Steve (Gary Smith), Stephen Childs (Douglas) and Vicky (Sara Nicholls), on a school trip, to uncover the truth. Norman Bird is suitably shifty as the superficially friendly Mr Danvers and Peter Copley is his reliable self as the main schoolteacher.

I’m convinced that if The Hostages weren’t a CFF production – if aimed at wider audiences, it would probably have had to be half an hour longer – it would be better known. It’s one of the CFF’s ventures into thriller territory which doesn’t softpedal things at all, and is played absolutely straight. We begin with four men running across fields in semi-darkness following a jailbreak and we follow two of them: Joe (Ray Barrett) and his younger sidekick Terry (Robin Askwith). As the radio broadcasts warnings that the men are at large, the Williams family at Piper’s Farm go about their business. While the parents and older daughter are away at the market, the three youngest are left behind, just as Joe and Terry turn up…

Something of a junior take on The Desperate Hours, The Hostages becomes very tense in places, well directed by David Eady (who spent his career with films like this, as well as documentaries). Askwith was a big star at the time due to the Confessions films, though I doubt there would have been much crossover in audiences from those films to this. While we’ve certainly seen Ray Barrett play tough guys before, it’s a departure for Askwith and it works. Barrett was an Australian who had worked in the UK since 1957 and who returned to his home country later in 1975.

Before he was a fixture on the children’s television watched by those of a certain age, Keith Chegwin was a child actor. He meets a nasty end in the Roman Polanski version of Macbeth (1971), where he played Fleance. Here he has the lead role, in what isn’t far from a straight version of one of England’s leading national myths, except that Robin, his Merrie Men (except for Friar Tuck, played by Andrew Sachs) and Maid Marion are all children. The rest of the cast are adults, the main adversary being Maurice Kaufman as the wicked Baron who currently has care of young Marion (Mandy Tulloch). With her father away at the Crusades, the Baron plots to poison him and then strongarm Marion to sign the castle and all that goes with it over to him. But she escapes and finds her way into the forest. Twenty children are held until Marion is returned, but Robin frees them and they all fleet to the same forest.

The lead character might be called Robin and he might dress in green tunic and tights, but the film is quick to distinguish him from the real Robin Hood, who is no doubt elsewhere than on screen. Plenty of action, a good few stunts and not too much gadzookery in the script makes for an entertaining hour.

This is an unusual CFF film, or British film from any source from its time, in having a principally black cast. Salu (Gordon Hagan), son of the ambassador from the small African country of Busandi, is kidnapped when he lands at Heathrow and is taken to a remote house where his father is captive. The plan is to assassinate the country’s president by presenting him with a gift by Salu’s double Ubu – a gift containing a bomb…

Directed by Frank Godwin, this is standard stuff, with enthusiastic if not especially adept performances from the young cast. (With many of these productions, conversations are shot with separate shots for each speaker, so as to edit around the actors’ inexperience.) It’s a boy-only affair for the most part, apart from Melissa Wilkes as a girl who helps Salu out but has motives of her own. Offered a watch, she asks, “Is it digital? Oh well, then.” Time was when a digital watch was the height of sophistication.

Children’s Film Foundation Bumper Box Vol. 5 is, like its predecessors, a release from the BFI comprising three dual-layered DVDs encoded for all regions. All the films, features and shorts alike, had U certificates on their original releases. However, four of them are now PG: Circus Friends for some language now considered discriminatory and The Hostages, Robin Hood Junior and The Boy Who Never Was for various degrees of threat.

All the films are transferred in a ratio of 1.33:1, except for Daylight Robbery which is 1.66:1 and anamorphically enhanced. That, or rather 1.37:1 (Academy ratio), is certainly correct for The Secret Tunnel, made before the widescreen era, and looks like it is for Bouncer Breaks Up!, which was made in 1953, the year that era began. A Good Pull-Up, from the same year, looks more framed for widescreen. By the end of that year and into the next, British studios were only a little behind their American counterparts by shooting in widescreen – if not in CinemaScope or other anamorphic processes, then “flat” in at first a variety of different ratios. Once cinemas had converted, there was no going back and, other than arthouses and repertory cinemas and venues like the then-new National Film Theatre, they could no longer show Academy. The CFF’s films were 35mm productions for commercial cinemas, and by the middle of the 1950s would have been composed for widescreen. Granted they were mostly shot open-matte (Daylight Robbery is likely an exception, shot at least partly with a hard-matte, hence its widescreen presentation on this disc) and would have had an afterlife in 16mm at schools, libraries and the like, or potentially sales to television down the line. But that doesn’t mean that they shouldn’t be presented correctly. Giveaways include the amount of headroom in most shots and occasional adjustments to keep things in frame which wouldn’t have been necessary if the films were actually intended for 4:3. Although this is a subjective call, watching Daylight Robbery in its intended ratio or close to it does make the film seem more cinematic.

All at Sea

As for the transfers, they come from various print materials held by the BFI National Archive, often negatives or interpositives. Clearly much is dependent on the state of those materials, but on the whole the results are good. Greyscale is rather lacking on Circus Friends, but on the whole contrast on the black and white films is what it should be. There is some print damage in the places where you often find it, usually at the beginnings and ends of reels (with films of this length, usually three or four), such as scratches and specks and visible splices: The Hostages in particular. That film also shows some aliasing on rooftops and some moiré patterns caused by the checks of Robin Askwith’s jacket. The extras on these discs show quite a bit of damage, with A Good Pull-Up looking particularly soft.

As these are PAL DVDs, the transfers are at twenty-five frames per second instead of the cinema speed of twenty-four, resulting in a speed-up of one minute in every twenty-five. This also means that the soundtrack is raised about half a semitone higher than it should be, but unless you have perfect pitch you’ll be unlikely to notice.

The sound is the original mono in all cases, presented in Dolby Digital 2.0. These soundtracks were the work of professionals and there’s nothing much to say about them, as dialogue, effects and music are what they should be. As with the visuals, there is crackle and hiss in places, in some cases due to similar damage that there is to the visuals. Unfortunately there are no subtitles for the hard of hearing available.

Bouncer Breaks Up! (8:27)

As well as the three- and four-reeler main attractions, this release also includes the single-reeler films and documentary magazine items which would have supplemented them on a Saturday morning at the local fleapit. Disc One has Bouncer Breaks Up!, an inventive short from 1953. In this black-and-white live-action world Bouncer is a powder-blue animated rabbit who gets up to all sorts of hijinks in eight minutes. It’s ably directed by Don Chaffey and shot by Norman Macqueen, whose career was largely spent on much more serious-minded animated instructional films than this. The mixture of black and white and colour necessitated this being printed on colour stock, which gives the monochrome a greenish tint throughout, and there’s a fair amount of print damage.

A Good Pull-Up (16:30)

We met Peter Butterworth’s Dickie Duffle in Volume 3, and here he is again, in another of the six short comedies he made for the CFF, It’s much as before, as the hapless Dickie – a rare adult lead character in a children’s film, though “adult” is clearly relative – causes damage at a roadside cafe and has to work there to pay for it. Also directed by Don Chaffey in 1953, it’s basic slapsticky stuff but over soon enough. “The comedian does not seem a very attractive character to put before children,” sniffed the Monthly Film Bulletin.

The Magnificent Six and ½: Ghosts and Ghoulies (19:46)

On to Disc Two, and the CFF’s bill of fare did include a few serials and also some series like this one from 1967 six self-contained shorts all featuring the seven children of the title, the half being the youngest, Peewee (Kim Tallmadge). After a first-half runabout, the children find themselves in a rather murkily-lit haunted house. It’s all played for laughs rather than scares. The series was so successful that two more were made, and it was also pitched unsuccessfully as a TV series, The reaction was that it didn’t have enough international appeal, so the premises was tweaked and the result was Here Come the Double Deckers! which ran for seventeen episodes in 1970, a year later in the UK, and which launched the careers of among others Peter Firth and Aswad’s Brinsley Forde.

The Chiffy Kids: Decorators Limited (16:18)

The Chiffy Kids was another series of shorts, this time from 1976: we saw another on Volume 4. If The Magnificent Six and ½ begat the Double Deckers, there’s more than a hint of influence of that show in this new series, which began in 1976. Mrs Foster (Peggy Mount, actually billed as “Battleaxe” so playing to type) hopes to win an interior decorating competition, so hires some men to redo her flat. Our five children volunteer to redecorate the flat of the two elderly sisters who live next door. Confusion ensues. As well as Mount, well-known adults in the cast include George A. Cooper and, towards the end, William Rushton.

Danger at the CFF (15:39)

On Disc Three, after his look at CFF locations on Volume 4, young Edward Molony hosts a short piece on the stuntwork in the films. Many of them are edge-of-seat stuff but would certainly not be allowed to be done nowadays, and certainly not by children. There are plenty of clips, some of them pointing out famous names on screen (such as Arthur Mullard and a young Frazer Hines) and there is input from the director of The Battle of Billy’s Pond and The Glitterball, Harley Cokeliss, and Edward’s actor older brother Alexander.

Our Magazine No. 11 (9:22)

Finally, something to learn about among the thrills and spills and laughs. Our Magazine was a regular item in children’s matinees in the 1950s. This is the eleventh edition, from 1955. As ever, it comprises four brief items. We see some German children hiking in the Black Forest, are told about road safety for cyclists, visit a toy museum and finally watch and listen to a team of schoolgirl bellringers performing “Greensleeves”. You wonder how much attention the audience would have paid to this while waiting for the main feature to start. The rather paternalistic voiceover is certainly from another age.

Booklet

The BFI’s booklet, available for the first pressing of this set only, runs to thirty-two pages. As before, it’s dominated by Vic Pratt, BFI producer (this set included) and authority on the CFF. Similarly to the previous sets, the tone, bordering on kitsch at times, leads one to suspect that the audience for this set isn’t children at all but nostalgic adults. His main essay gives an overview of the CFF’s history which will be familiar if you own any of the previous Bumper Boxes. Pratt also provides the notes for all the films and extras, except for Danger at the CFF, which are by the documentary’s producer and director Jason Gurr. Robin Askwith provides a brief note for The Hostages which is full of praise for the CFF. They employed him three times: the other two are Scramble (1970) and Hide and Seek (1972), all like the present film directed by David Eady and in each he was cast as a villain.

Finally, Pratt’s co-curator Trevona Thomson sets us a quiz just to make sure we were paying attention. There are also plenty of stills.

There are plenty of CFF productions out there and once again the BFI has collected nine of them from various times, black and white or colour, onto three discs. At their best the films are well-made and entertaining and often showcase performers and filmmakers before they became better known. You certainly get value for money.

|