|

If you've not before heard of the World Cinema Foundation then I can only presume you are not a world cinema devotee, that you have not been keeping an eye on Eureka's Masters of Cinema release schedule and that you have stumbled across this review by chance. Set up in 2007 and overseen by filmmaker and passionate film devotee Martin Scorsese, its mission, to quote the press release for this dual format set, is "to preserve, restore, and annually re-present neglected masterpieces of world cinema, particularly those from areas of the globe that have not traditionally been highlighted in prevailing evaluations of film, or which have lacked the financial, technical, or governmental infrastructure to ensure their preservation."

Much as I despise the current trend for every business with a lofty opinion of itself to have what has come to be known as a 'mission statement', I find myself having to salute the intentions outlined in the one drafted by the WCF:

"Cinema is an international language, an international art, but, above all, it is a source of enlightenment. There are wonderful, remarkable films, past and present, from Mexico, Eastern Europe, the Middle East, Latin America, and Central Asia that deserve to be known and seen. Composed of filmmakers from every continent, the World Cinema Foundation breathes life into the idea that when a cultural patrimony is lost, no matter how small or supposedly 'marginal' the country might be, we are all poorer for it."

The WCF's efforts may only make a small dent on the wealth of world cinema that goes unseen outside of – and sometimes even inside of – the country in which it was produced, but their work is still to be applauded and the results of their endeavours treasured.

This first of what we can hope will be many collections contains three films that have been rediscovered and restored by the Foundation. Despite having no preconceptions about what I was to see, I was genuinely surprised by the variety of the three films in this set, in style as well as content and country of origin. We have films from Turkey, Morocco and Kazakhstan; a contemporary drama, a historical drama and a documentary; two were shot on 35mm, one on 16mm; and two are in colour and one in radiant monochrome. And all three a markedly different films, linked only by their consistently high quality and previous rarity. Watching all three in a row is like overdosing on a range of the finest chocolates – you almost need a break between them to savour what you've tasted before moving on to the unique flavours that the others have to offer. But savour them you should, however you choose to watch them, and wonder as you do so how such remarkable cinema could have spent so long in virtual obscurity.

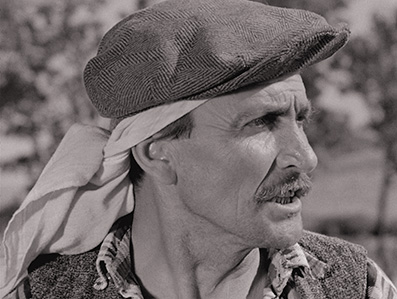

During a particularly arid Turkish summer, tobacco farmer Osman Kocabas decides that as the spring that provides water for all the surrounding farming properties is located on his land, then that water belongs to him and should no longer be treated as a communal resource. Despite being informed of his intentions, his neighbours find it hard to believe he will actually act on such a selfish promise. Even his younger brother Hasan is apprehensive about the decision, although his attention is primarily focussed on the beautiful Bahar, the girl he plans to marry after this year's harvest. Osman convinces Hasan to move the marriage forward and soon Bahar is working the fields alongside her new brother-in-law, who appears quite taken with his brother's young bride. All seems to be going well for the Kocabas clan, but when Osman follows through on his threat to cut of the water to the neighbouring farms, events take a dark and ultimately tragic turn.

Winner of the Golden Bear at the 1964 Berlin Film Festival, Dry Summer [Susuz Yaz] has all the audience-friendly hallmarks of a finely wrought melodrama, a kind of Lust in the Tobacco Fields set in the burning Turkish summer sun. Yet the film suffered many years of suppression by the country's authorities, which suggests that they saw it as a specifically Turkish story and one heavily critical of their own policies or actions. Maybe it is, I'm not in a position to say, but it also succeeds as a still relevant parable on the damage that unprincipled self-interest can inflict on communities and individuals alike.

Though Osman's decision is initially driven by his perceived need to protect his crops (and thus his only income) at any cost, it's one that takes little account of the potential consequences, transforming a once harmonious community into a hotbed of discontent and a potential battleground. Farmers who were already struggling with the dry summer of the title suddenly face the prospect of complete ruination, a situation that inevitably provokes desperate measures, one that casts Osman in the role of greedy and amoral landowner and his fellow farmers as oppressed serfs. The tragedy is that the victims seem unable to collectively organise and take the revolutionary action that by all rights they should. A legal challenge provides only temporary reprieve, and an attempt to open the offending sluice gate by night escalates the dispute to armed conflict and results in the death of one of the farmers. When a breakaway pair kill Osman's dog (be warned, this appears to have been done for real and you don't need to be an animal lover to wince at the results), they become symbolic of the striking workers whose angry sense of injustice prompts them to inadvertently fan the flames of escalating conflict.

As the story unfolds it becomes apparent that almost every misfortune is the result of Osman's selfish and manipulative approach to every aspect of his life, from his crops to his own brother and his brother's new wife. Yet it's one of the real strengths of Dry Summer that he is not portrayed as inherently evil, but as a man who becomes corrupted by material ownership and the power he is able to exercise over others. In this sense the film plays as a cry against private ownership and a call to revolution, though is almost as critical of those who suffer at Osman's hand as it is of Osman himself.

Winningly handled by director Metin Erksan (the speed with which the narrative advances is at times almost dizzying), Dry Summer is also a beautifully and purposefully photographed film, with prolific cinematographer Ali Ugur making sometimes striking use of the Academy frame, his telling use of close-ups recalling early Satyajit Ray and Bergman, while use of deep focus imagery is occasionally so startling that I began to suspect these were actually process shots (if so, they're bloody good ones). It's also interesting to observe just how often the camera is positioned to look upwards at Osman, subtly but effectively emphasising his position of power. Crucially the film also captivates as drama – this is no political polemic but a very human story whose narrative is driven by the destructive power of possession and anti-collectivism. It's a message that has lost none of its potency in a time when caring for our fellow citizens is curtly dismissed as economically unviable. And current studies suggest that in the not too distant future the film's metaphorical message will become more literal, as the world fights for possession not of oil or of land, but of the water on which our very existence depends.

The 1981 Trances is a documentary portrait of Moroccan musical combo Nass El Ghiwane, albeit something of an impressionistic one. There is little in the way of interview material and no explanatory captions or narration to contextualise the band's huge home turf popularity, though would presumably not be needed for a domestic audience familiar with them and their music. Initially playing like a multi-venue concert movie, the performance scenes increasingly share space with sequences showing the band in discussion with each other or third parties on a range of topics, and archive clips whose content and purpose will not always be clear to those not well versed in Moroccan social history (that includes me, by the way).

The term "trance" has in recent years found new musical associations, being the name given to a high velocity sub-genre of electronic dance music, so named for the hypnotic effect it can have on the (sometimes chemically aided) willing, and in this respect the music of Nass El Ghiwane shares common ground with its more recent western cousin. The difference here is that Nass El Ghiwane work with traditional instruments only (although not exclusively traditional Moroccan instruments), drawing on local Gnawa music to create an often hypnotic blend of driving rhythms, energetically plucked strings and Arabic singing. Its effect is clearly visible in the audience members who sway, dance and shake to the music as if genetically bonded to it, a drug to whose effects they willingly surrender.

It's in the focus on these dancers, on their faces and movements, that you first really appreciate the consistently excellent work of the camera team led by director Ahmed El Maanouni, who intermittently capture small stories in a single cannily framed shot. Nowhere is this more vividly illustrated than at the concert at which which police aggressively suppress some over-exuberant audience members, while the performing musicians remain unaware of the pandemonium that is unfolding directly behind them.

There's an almost cut-up feel to the non-performance footage, a series of seemingly unrelated vignettes that somehow seamlessly dovetail into each other and from which we glean small but sometimes telling snippets of information on the band and its members, though not enough to paint a comprehensive picture of any of them. We're teased with small details, including a heated debate about trust and dodgy contracts that hints at problems and possible disharmony that is never expanded on or even confirmed. The revelation that many of these scenes were carefully arranged will probably not come as a complete surprise (a few of them do feel too set up to have been spontaneous), and intriguingly links the film to the roots of documentary and Robert Flaherty's celebrated Nanook of the North, whose truth was as stage-managed as any drama.

Perhaps the most revealing off-stage sequence occurs towards the end, when the band talk directly to camera (and the off-screen director) and admit that although they love making music, if for some reason they were unable to do so then they'd simply find something else to do instead. It's a refreshingly pragmatic alternative to the usual claim by artists of all creeds that their art is their life and that without it they would somehow wither up and die.

But as demonstrated by the sometimes intoxicating performance footage, these men are first and foremost musicians and we can only be grateful that they met and formed this exceptional group. The music is the star here and rightly so, and watching and listening at home, even with sound cranked unsociably high, we can only imagine the bewitching effect it clearly has when experienced live.

A title like Revenge can't help but create certain expectations. The revenge movie, after all, has become a fully fledged sub-genre in its own right, one with its own very specific pleasures, conventions and moral quandaries. It's that last characteristic in particular that has prompted a number of filmmakers in recent years to suggest that revenge does not bring the cathartic satisfaction for which the form has become famous, but is ultimately as harmful to the revenger as it is to his or her intended target. That's certainly the case with the film under discussion here, a story of a thirst for vengeance that consumes one man's world and goes on to define the life of another.

Following an intriguing prologue set in 17th century Korea whose connection to the what follows requires a little dot-joining, we hop forward to 1915, where a temperamental rural schoolteacher named Jan loses his rag at the young daughter of a family with whom he was once a tenant and murders her. The girl's middle-aged father Caj pursues Jan to China and eventually tracks him down, but before he can bring himself to take the action that has consumed his every waking hour, Jan is spirited away by a mysterious female traveller. When Caj returns home having failed in his quest, his ageing wife procures a younger peasant girl to bear him a son, so that the boy might later seek the revenge in his father's name.

Structured as a series of titled and sequentially connected tales, Revenge unfolds as a mesmerising minimalist poem, moving forward in sometimes substantial jumps but in a manner that allows and encourages us to fill in the narrative gaps. Viewpoints shift as the story progresses, the brief spell with Jan followed by a longer one with Caj before finally settling on Sungu's quest. There's even an unexpected but exquisitely timed flashback to reveal the true reason behind the mysterious woman's rescue of the nefarious Jan.

Here the act of revenge is presented as an infection that can be passed on through the generations but ultimately brings no real sense of resolution or justice. Sungu in particular owes his very existence to his father's thirst for vengeance, having been bred solely for the purpose of avenging the death of a half-sister that he never even knew. Once charged with his task it shapes the course of his life as unwaveringly as love or vocation might for others, robbing him of a natural gift that in different circumstances would allow him see the world through more positive eyes, in the process transforming him from a poet into a potential killer.

Written by Russian-Korean author Anatoli Kim and featuring some gorgeous natural light cinematography by Sergei Kosmanev, Revenge does require a little knowledge of the locale and its history for full appreciation (there were elements I was completely unaware of until I read the accompanying booklet), but is not reliant on either to captivate as a drama, thanks in no small part to the economy and poetic restraint of Ermek Shinarbaev's measured direction. Structured as an inter-linked collection of short stories with the tone of an ancient fable, it leaves the viewer in no doubt that the single-minded pursuit of revenge ultimate robs even the best intentioned not just of the joy of life, but their humanity.

All the three films have been restored by the World Cinema Foundation and the process undertaken for each is detailed in the accompanying booklet, quotes from which are included here in italics. Although a dual format set that includes Blu-ray and DVD copies of the films and extra features, all of my comments below refer to the Blu-ray versions.

Dry Summer

The restoration of Dry Summer used the original 35mm camera negative and the original 17.5 mm sound negative and recaptured the black and white film's tonal nuances. The film's producer, Ulvi Dogan, provided the prints. An interpositive preserved at the Friedrich Wilhelm Murnau Stiftung in Wiesbaden was used for the negative's last missing reel. The opening and closing credits, missing from all available sources, have been digitally reconstructed.

The resulting image, which is framed in its original 1.37:1 ratio, is strikingly good, with a genuinely lovely tonal range, crisp picture detail (the close-ups on animals, faces and textured surfaces are particularly eye-catching), not a trace of picture jitter and hardly a dust spot to be seen. Black levels are strong without sacrificing detail in darker areas, and a slightly less generous contrast range is the only concession made to the switch from negative to release print in the final reel. The film grain is visible, but only just, a benefit (I presume) of shooting on low speed stock in bright sunlight. Honestly, if the were reshot today I doubt you could improve much on this. A terrific transfer.

The Linear PCM mono 2.0 soundtrack is initially somewhat harsh due to post-dubbed dialogue that appears to have been recorded at a higher volume than required, resulting in voices that sometimes feel a little divorced from their on-screen delivery and that seem to shout when the characters are clearly speaking at normal volume. I was surprised how quickly I got used to this, however, which you can doubtless chalk up to the involving nature of the drama. The track is otherwise clean and free of damage.

Trances

The restoration of Trances used the original 16mm camera and sound negative provided by producer Izza Génini. The camera negative was restored both photochemically and digitally and blown-up to 35mm format. The sound negative was restored to Dolby SR and digital.

There will doubtless be some who will be a little disappointed by the more visible film grain, slightly softer image and less generous shadow detail that result from Trances being shot on 16mm in available light, probably on high speed stock. Not me matey. 16mm is the only film format I have worked with as a cameraman (I've worked with 35mm as an assistant, but have not had the opportunity to light and shoot with it) and I have a real fondness for the look and feel of the medium when decently graded and presented, and that's just what we have here. Like the transfer on the Masters of Cinema Blu-ray release of Soul Power, the 1.66:1 image here has that unique tonal warmth and pastel colouration that I instantly associate with 16mm film, and a look that works well for the immediacy of documentary. And when required, those colours really are vibrantly reproduced (the brief shot of the local woman painting her doorway blue – captured above – pops from the screen). As with Dry Summer, the picture is spotless and completely stable throughout. Another terrific restoration.

The Linear PCM mono 2.0 soundtrack is generally clean (there is background hiss audible on silent archive footage, but this may appears to be deliberate) and demonstrates a reasonable dynamic range. Certainly the music sounds good, and while it lacks the fidelity you'd find in more recent music-orientated films (there's little in the way of bass and a treble bias to the singing), there is no sign of distortion in even the louder sequences.

Revenge

The restoration of Revenge used the original camera negative, the sound negative, and a positive print provided by the Kazakhfilm Studio and held at the State Archive of the Republic of Kazakhstan.

Director Ermek Shinarbaev was actively involved in this restoration.

It's easy to be fooled by the some of the imagery here – including that of the prologue – into thinking that there's something a bit off with the transfer, but the overexposed and glowing highlights are clearly a deliberate decision on the part of director Ermek Shinarbaev and cinematographer Sergei Kosmanev, as evidenced by the more naturalistically exposed and graded imagery elsewhere. It's an approach that does result in some burned-out whites and sometimes softer detail, but it always feels very much part of the film's visual aesthetic and adds to the sense that we are watching a poetic fable. Elsewhere the image quality is fine, with a good level of detail, well balanced contrast and an attractively low-key rendering of colours. Again the transfer is spotless and free of damage.

The Linear PCM stereo soundtrack probably has the best dynamic range of all the soundtracks here, though this is more evident in the reproduction of the music and sound effects than the dialogue, which has a slightly harsher edge. There is no trace of noise or damage here.

Each film can be played with a short optional Introduction by Martin Scorsese, who provides a brief overview of the film and its fortunes and why the WCF selected it for restoration.

The Booklet includes essays on all three films – Phil Coldiron on Dry Summer, Bilge Ebiri on Trances and Kent Jones on Revenge – that as well as discussing the works themselves, helpfully provide some detailed social and political background to the stories and characters. Also included are the main credits for all three films, some quality stills, details of the restoration, and notes on how to correctly view the films.

Three remarkable world cinema feature films that you've probably never seen, all in one package on both DVD and Blu-ray, restored and looking as good as new. How can you resist? And the great news is that this is just volume one, and you only include that in the title of the package if you're planning to release further volumes at a later date. Personally, I can't wait. Highly recommended.

|