| |

"Let me say another thing. I hope this is going to be put on the tail end of this. When you walk out of this movie, if you walk away from your television set, there's one thing you walk out with in your mind. When you get up and walk out and look down the street, you say to yourself, "Damn right I'm somebody." |

| |

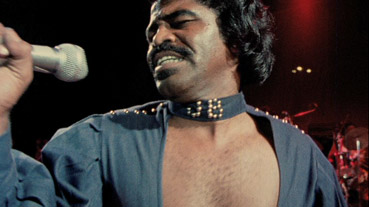

James Brown, Godfather of Soul, at the tail end of Soul Power |

A couple of years ago, a Japanese friend of mine asked me to explain to her what soul music was and I found myself stumped for an answer. It's not that I didn't know, it's just that I couldn't for the life of me put it into words. The more I thought about it, the more it struck me that the same thing went for just about any musical genre. Put it this way, I know soul music when I hear it – or at least I think I do – but I'm still not sure I could accurately summarise what defines it.

I'll state up front that I've always been a little ambivalent towards soul music, aware of its influence, able to recognise key players and songs, but owning precious few tracks that would comfortably sit under that musical umbrella. I'm not sure I've ever listened to an entire soul album in one sitting. And here I was, charged with reviewing a film called Soul Power, whose centrepiece is a concert in which some of the genre's most respected figures do their stuff. And if it's all about the music, was I really qualified to pass judgement on it? After all, if I didn't like it, would it be because it's just not my thing? So before I continue, I need to make three things clear. First, Soul Power is not all about the music. Secondly, as someone not fully versed in the pleasures of soul and R&B music I was able to respond to the acts on the merit of their performances here rather than their reputations or work elsewhere. Thirdly, and most importantly, the concert, the performances and the music itself absolutely blew me away.

Although deserving to stand on its own cinematic feet, Soul Power inevitably functions as a companion piece to Leon Gast's 1996 When We Were Kings, and with good reason, as the two are linked both by the events they portray and the shared lake of footage from which they both draw. For those not in the know, When We Were Kings told the story of what became known worldwide as 'The Rumble in the Jungle', a celebrated 1974 boxing match in which Mohammed Ali took on George Foreman in an attempt to regain the world heavyweight title that was taken from him after he refused to fight in Vietnam. Organised by sports showman Don King, the bout was to be held in Zaire and accompanied by a music festival – conceived by record producer Stewart Levine and South African trumpeter Hugh Masekela – that was to feature some of the leading lights of American soul and African music. Originally designed as a promotional event for the fight and expected to play to the international crowd this titanic clash was expected to attract, the festival faced possible cancellation when an injury on Foreman's part led to the fight being postponed for six weeks.

With preparations for the festival already well under way, the decision was made to go ahead anyway – a capacity local audience was guaranteed (an estimated 80,000 attended) and the event's sizeable budget included a provision to pay for a top flight film crew to record the whole thing for posterity. But after shooting over 125 hours of sometimes priceless footage, the filmmakers were forced by legal wrangles with the Liberian financiers to put the project on hold for a staggering twenty-one years. Leon Gast used some of the footage in When We Were Kings, which won the Best Documentary Oscar but focussed largely on the build-up to the fight and used only a sprinkling of the available concert material. One of that film's editors, Jeffrey Levy-Hinte, became fixated on the idea of revisiting the wealth of unused material with the intention of creating a series of DVDs covering all of the performances in the festival. His quest eventually led to the creation of a single theatrical feature (at least for now), and thirteen years after When We Were Kings and thirty-four after the film material was first shot, Soul Power was born.

There are some structural similarities to Gast's film in the first third build-up to the main event, and there was clearly plenty of material to pick from here, of James Brown introducing his fellow performers to an eager American press, of Ali talking about the public misconception of Zaire (New York is more of a jungle, he claims), of the musicians jamming on the plane, of Ali's first meeting with Brown and a meal shared with locals, of the acts rehearsing and preparing in their dressing rooms. The shift from multiple DVDs to a single feature has forced director Levy-Hinte and his editor David Smith to narrow their focus a little, but their tightly structured 93 minutes still economically succeeds in capturing the scale and charged atmosphere of the festival and the sheer range and quality of performers taking part.

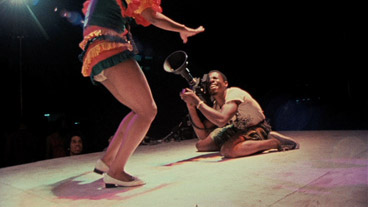

It's in the three-night festival itself, of course, that the film really comes into its own. It's notoriously difficult to capture the true essence of a live concert on film or video, and our over-familiarity with the form – almost every group worth their salt has at least one concert DVD available – can make us a little blasé about the merits of even the best of them. The restrictions placed on camera angles has led to its own set of visual clichés, particularly the modern fondness for crane shots that swoop over the crowd and up into the air like an eagle preparing for a dinner-catching dive. Soul Power is a very different beast, with a primo camera team made up of Paul Goldsmith, Kevin Keating, Roderick "Kwaku" Young and the legendary Albert Maysles given what looks like full access to every inch of the stage,* which infuses the camerawork with a sometimes thrilling energy and intimacy, and collectively provides a masterclass in how to shoot live music.

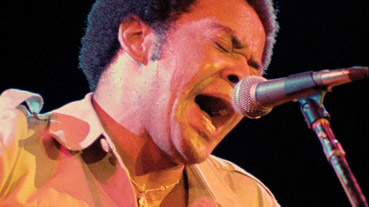

The acts themselves are a joy. Not long after the concert itself kicked off I stopped my customary note-taking to just bathe in the music and the on-stage dynamism of the performers. Every number left me opened mouthed and wide-eyed in appreciation, and prompted guilt at some gaps in my CD collection. Highlights include – and I'll probably end up listing them all because it's impossible to single people out – the synchronous euphoria of The Spinners and OK Jazz, the emotional power of Bill Withers, Miriam Makeba's extraordinary 'Click Song', the towering brilliance of B.B. King, the costumed liveliness of the Pembe Dance Troupe, the jazz-influenced R&B of The Crusaders, the calypso vigour of the Celia Cruz and the Fania All-Stars, the furious rhythms of drummer Big Black, and the ska-flavoured exuberance of Tabu Ley and Afrisa. It all builds to a climactic performance by the great James Brown, and from the moment he takes the stage you're left in no doubt as to why he was and still is held in such high regard, as he explodes into song and dance and radiates the sort of star power and passion for his craft that makes me wish I had just an ounce of musical talent.

All of which brings me full circle back to my Japanese friend from the opening paragraph, who by chance paid me a visit when I was watching this very film and was thus able to get a clearer answer to her original question than I was able to verbally provide. She quickly became caught up in the live performances, and as she watched BB King giving his guitar a serious workout, she remarked, without taking her eyes of the screen for a second, "I don't know who this is, but he must be some kind of genius." Enough said.

The footage from which Soul Power was constructed was all shot on 16mm, very likely on high speed stock and always in available light, which in the case of offices and dressing rooms was far from ideal. The image is thus rarely pin-sharp and sometimes very grainy, while the colour on some of the less camera-friendly location work is on the faded side. But this is still a delicious transfer that matches the high standard Masters of Cinema have set for their releases, with generally spot-on contrast (it does fade a little when the light levels are weak and just occasionally detail is lost in darker areas), naturalistic colours and a very decent level of detail. It's in the on-stage concert material that the image really shines, with the stage lighting providing the punch and depth-of-field that film just loves, resulting in some wonderfully rich visuals that are given extra vibrancy by the multi-coloured stage lighting and the intoxicating love affair between the camera and the performers.

The differences between the DVD and the Blu-ray at first seem minimal, at least if your DVD player/TV combination knows how to upscale well. This is partly due to the high speed 16mm source material, which doesn't quite have the definition needed to really show off the capabilities of high-def playback, but mainly down to how good the DVD transfer is. But take a closer look and the extra detail is clearly visible on the Blu-ray and the best material has an even greater richness and punch. That said, you can also see every crisp speck of grain in the shots where it is prominent.

And then there's the sound. On the DVD you have a Dolby 5.1 soundtrack only, but it's one of the best I've heard all year. In the interview included on this disc, director Levy-Hinte states that the original budget allowed the use of high-end sound recording equipment and it really shows – the concert footage audio is consistently superb, with an excellent dynamic range and clarity, very distinct stereo separation (Big Black's drums move across the sound stage in time with his movements) and no trace of clipping or distortion.

A Dolby 2.0 stereo track is included on the Blu-ray, but there you can also choose between Dolby TrueHD 5.1 and DTS Master Audio surround tracks, where the sound is more widely spread (audience reaction at the concerts is precisely placed) and has and noticeably increased clarity and punch. In a two-horse HD race it's the DTS track that emerges the clear winner, being louder and having even more musical wallop than its Dolby companion.

There are five Extra Scenes, which I'm assuming were originally intended for inclusion as they are edited and of similar quality to the main feature, although along with the other extras have been transferred on the Blu-ray at 480p. The most substantial is Concert Logistics (10:02), which provides a welcome behind-the-scenes look at the preparations for the festival and the logistics of staging an event of this size. Ali Departs in Car (1:21) gives us a quick burst of Ali in one of his famed verbal performances to the camera. Jams and Rehearsals (5:51) is a seductive peek at a couple of the groups preparing for the big night and further emphasises the collective talent of those taking part. Boxing Organisers (2:47) features the fateful phone call in which the festival organisers discover for the first time that the fight has been postponed. Zaire 1974 (5:54) takes us into the local township to observe the everyday lives of the people who live there – the size of the living grubs being sold (and eagerly bought) for food at the local market is guaranteed to give those with a phobia for their smaller brethren the heebie-jeebies.

Also edited, presumably for intended inclusion, are five Extra Performances, a welcome inclusion for anyone who could willingly have watched another couple of hours or so of the festival performance footage. The tracks are James Brown – 'Try Me' (3:45), Sister Sledge – 'On and On' (4:27), two unnamed numbers by Abeti (5:00), The Pointer Sisters – 'Yes We Can (Can)' (5:27), and an extended performance by the Pembe Dance Troupe (2:12).

In the Director Interview (6:01), Jeffrey Levy-Hinte talks about the response to the film, the quality of the original material, the inception and evolution of the project, the reaction of the surviving participants, and more. He's clearly still attached to the idea of a DVD set covering the entire three-day festival, and even tosses in a casual appeal for funds to get the project under way.

The UK Theatrical Trailer (1:57) is a very nicely cut sell for an equally well edited feature.

Finally we have the always well produced MoC Booklet, which contains a Director's Statement, various quotes on the Zaire '74 Music festival, credits for the film and disc and a number of quality stills.

If you're a fan of When We Were Kings then this is a crucial companion piece. If you're a lover of classic soul, R&B and/or African music then consider it an essential purchase. If, as I was, you're not as well versed in the music or the performers as you should be then you'll find no better introduction. A marvellous concert film of what was clearly one of the great music festivals of the modern age. Will someone please give Levy-Hinte the money to get the rest of the material out on disc? Masters of Cinema's DVD looks and sounds terrific, the Blu-ray is even better. Very highly recommended.

* During the concert the cinematographers are repeatedly caught on camera by their colleagues, which both illustrates how close to the action the camera operators were getting and telegraphs where the next edit might take us.

|