|

– Part Three –

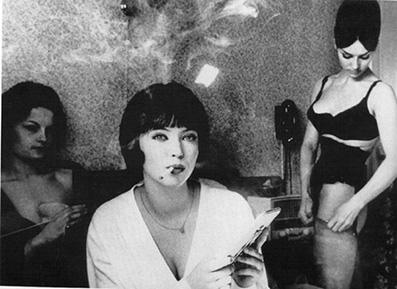

While Godard's treatment of prostitution isn't explicit or exploitative, his relationship with Karina complicates matters, to say the least. In Images of Women, Images of Sexuality, an essay co-written with Colin MacCabe, Laura Mulvey says: "More than any other single film-maker Godard has shown up the exploitation of woman as an image in consumer society . . . but his own relation to that image raises further problems . . . Godard slides continually between an investigation of the images of woman and an investigation that uses those images."

Mulvey is best known for her iconic essay, Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema, which invented the notion of 'the male gaze'. In it, she says: "In a world ordered by sexual imbalance, pleasure in looking has been split between active/male and passive/female. The determining male gaze projects its fantasy onto the female figure, which is styled accordingly. In their traditional exhibitionist role women are simultaneously looked at and displayed, with their appearance coded for strong visual and erotic impact so that they can be said to connote to-be-looked-at-ness. Woman displayed as sexual object is the lietmotif of erotic spectacle."

For all that Godard's treatment of prostitution is serious-minded and far from salacious, Mulvey's formulation fits Vivre sa vie like a glove: Godard is the active/male gaze, Karina passive/female object of desire. Earlier this year, I attended Birbeck's inaugural Essay Film Festival. In among the many films shown was one by Constaze Ruhm and Roland-François Lack called La difficulté d'une perspective/Une femme est une femme/Godard (2013). Introduced by Laura Mulvey, the film reversed the spectator's gaze by showing locations from Une femme est une femme and Vivre sa vie as they would have been seen from Nana/Anna Karina's perspective. It is a productive exercise in radical cinephilia that raised serious questions about Godard's use of Karina.

As Adrian Martin notes in his commentary on the BFI release, Vivre sa vie may not be salacious but the psychosexual dynamic of Godard's relationship with Karina raises troubling questions. Here is a director filming his wife, who has recently had a miscarriage and is suicidal, as a prostitute and casting her as a character killed at the end of the film. It cries out for a forensic feminist and psychoanalytical reading (which I lack the skills to conduct), so I offer a few biographical details – in the hope that they speak for themselves or that the (more capable) reader will fill in the gaps left by my analytical inadequacies.

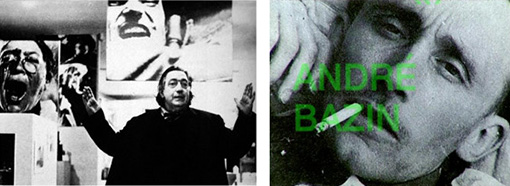

Godard, whose parents separated in his teens, was a 'troubled' youth. Although he came from haute bourgeois stock, he was a peripatetic misfit, a committed kleptomaniac who stole from colleagues, employers, friends and family alike. Godard is being disingenuous when he talks of a happy childhood. His relationship with family, particularly his father, was fraught. Father and son were estranged by the mid-fifties. While discussing Emmanuel Laurent's Deux de la vague (2010), I noted the role figures like André Bazin and Henri Langlois played in Godard and Truffaut's world as surrogate father figures.

Most of the directors most admired by the Cahiers critics –Bresson, Fuller, Hitchcock, Lang, Mizoguchi, Ray, Renoir and Rossellini – grew fond, in their turn, of the Young Turks. The respect was mutual. It amounted to a series of successful father-son relationships within the family of cinema. More precisely, it was a series of surrogate father-son relationships, as the experienced masters often 'replaced' actual fathers. As film theorist Thomas Elsaesser suggests in his essay Cinephilia or the Uses of Disenchantment, the Young Turks' insolent oedipal revolt against the 'cinéma de papa' represented a rejection of papa as much as a declaration of war on the New Wave's cinematic enemies.

After Godard was caught stealing from a Swiss TV company he spent three nights in jail and, subsequently, his father consigned him to a few months in a mental hospital, Le Grangette near Lausanne. This did not stop Godard stealing. He was soon in trouble again, after being caught filching and flogging his grandfather's valuable signed first edition copies of Valéry (who was a family friend). The clinician who treated Godard, Dr Mueller, considered him neurotic. It can't have helped that his parents split up during this crisis his life, his mother was killed in a car crash two years later, and he wasn't allowed to attend the funeral.

Little wonder that Godard's sister was concerned that he kept a razor blade on his person at all time, should he ever feel the need to commit suicide. You don't have to be a qualified psychologist to see Godard's kleptomania as a desire to be caught and punished or his razor blade as a sign-posted cry for help. It is surely significant that Godard advertised his possession of the razor blade and that he sold the stolen Valéry titles at a local bookshop close to home.

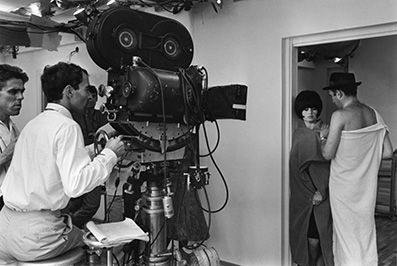

After Karina fell pregnant during the shooting of Une Femme et une femme (in which Karina plays a woman desperate for a child), Godard and Karina decided to marry. They did so twice: first in Switzerland and then in France. On 3 March, 1961, in Begnins near Nyon, where Godard père practised medicine and Godard fils studied classics during the war, and, again, three weeks later, in Paris.

It is unsurprising that their relationship was tempestuous from the start because both had unsettled upbringings and were emotionally insecure, even 'damaged'. Karina grew up feeling unloved and unwanted: in the absence of her biological father, she was raised first by her maternal grandparents, then in various foster homes, and finally in the house her mother shared with her second husband. In 1958, after a blazing row with her mother, Karina left for Paris. The 18 year-old Dane found love almost immediately when she met Godard, but his tendency to disappear without warning for weeks on end can only have done serious damage to her emotional stability and exacerbated her suicidal tendencies.

Karina, too, had her neuroses and they were intensified during the shooting of Vivre sa vie by a miscarriage that lead to several suicide attempts. After she narrowly survived an overdose of barbiturates, Godard committed her to a mental asylum. What can one say of a man who portrays his young wife first as a stripper and then as a prostitute, whom he films being killed; of a man who, having come through an asylum himself, imposes that experience on his wife and asks others to pick up the pieces of problems he himself partly precipitated? At minimum, that he probably wasn't as supportive as he might have been.

All the evidence suggests that Godard damaged the lovely woman he loved and who loved him. I'll neither forget nor forgive one particular moment of cold-hearted cruelty. In Michel Royer's film Godard à la télé: 1960-2000 (1999), we watch archive footage of a sofa appearance by Godard and Karina on a primetime TV chat show in the eighties. When the invasive interviewer presses the estranged couple about their relationship, Godard says: "Well, I said to myself, after all, there was Orson Welles and Rita Hayworth, Sternberg and Marlene Dietrich, Renoir and Catherine Hessling, so I thought to myself, 'I want that too! . . . and tomorrow is always a new day." Karina is reduced to tears. Godard spurns the opportunity for tenderness. He even throws out an arm to restrain his ex-wife. He makes no attempt to console her and she flees the set in pieces.

Controversially, I don't think Godard's early views of women and his contemptuous treatment of Karina, the cinematic misogyny and the general odiousness of his behaviour, negate the brilliance of his work. Nor does Louis-Ferdinand Céline's virulent anti-Semitism negate the genius of Journey to the End of Night or the Nazi sympathies of Francis Stuart and Knut Hamsun invalidate the achievements of Black List, Section H or Hunger. It may be in bad taste to rake through the coals of Godard and Karina's personal past, as that interviewer did and I am doing, but it is surely legitimate to do so given the ways that relationship is stitched into the films.

Karina said of her relationship with Godard: "It was amour fou. Love. Jealously. Revenge. We adored each other. We were passionate, but we had crises of jealousy." Godard and Karina, in fact, had frequent violent rows in which flats and their contents were destroyed. Their relationship was punctuated by repeated separations and reconciliations. Under such chaotic circumstances, with infidelities on both sides placing additional strain on the marriage, it surprising that Vivre sa vie it is so well ordered, unsurprising that it becomes increasingly dark. The block colours, the bright reds and blues of Une femme est une femme are replaced by sombre black and white, the score shifts from jaunty jazz to melancholic neo-classical fugues, the tone becomes dour.

Although Godard returned to colour in Le mépris – which delineates the disintegrating marriage of Camille (Brigitte Bardot) and Paul (Michel Piccoli) – he deliberately and subconsciously continued to draw his fraught relationship with Karina into his work. Bardot wore black bobs à la Karina, delivers dialogue that includes things Karina had said to Godard, and was even asked to walk like Karina. Piccoli wore Godard's hat. The film features a poster of Vivre sa vie juxtaposed with one for Psycho. By the time of Band à part, a crisis point had been reached. As Karina says: "That film saved my life. I had no desire to live. I was doing very, very badly." Pierrot le fou is Godard's angry farewell letter to Karina. The atmosphere during the shooting of that film was famously bitter, poisoned by Godard and Karina's constant fights. Karina's co-star Jean-Paul Belmondo says they were "like a cobra and a mongoose, always glaring at each other." Godard was lucky to find Karina and foolish to lose her; she was lucky to find him too and equally lucky to survive him; we are lucky that, together, they produced several of the finest, most beautiful films made, anywhere, by anyone.

The Passion of Anna Karina |

|

Anna Karina's stunning looks meant she didn't receive the credit she deserved for her acting. Her timing was perfect, her capacity to act naturally in front of a camera almost unsurpassed. Above, I touched on a few of the reasons I was drawn to Godard. I'll close with another couple of reasons: Nana/Karina's delightful 'mating' dance in the pool hall and the single imperishable scene in which Nana/Karina weeps while watching Maria Falconetti weep in Dreyer's La Passion de Jeanne d'Arc (1928). In his book The Films of Jean-Luc Godard: Seeing the Invisible, David Sterritt says: "Nana's tears are for Joan, for herself, and for a world in which the pitiless have a monopoly on power . . . Nana's double becomes the threatened and imprisoned Joan, so Karina's double becomes Maria Falconetti." Godard himself said: The film has a Satrean character in that it develops the idea that purity exists in everyone regardless of the way they have chosen to live. That's why I've inserted a sequence from Dreyer's La Passion de Jeanne d'Arc, to make plain the parallels between the heroine burning at the stake and the heroine of my film."

That ravishingly beautiful, heart-rending scene fits perfectly into the film. It shows Nana's inner sadness, it shows her pity and self-pity, but it goes beyond that. For me, it is a symbol of all cinema. Dreyer and Falconetti plus Godard and Karina equal cinematic heaven. Nana reflects the commonplace that the tears of others make us cry, but her tears are also those of rapture before the sublime. As surely as the majestic scene in Terence Davies's Distant Voices, Still Lives in which Eileen and Maisie dab at their tears with hankies while watching Love is a Many-Splendoured Thing (1955), this scene in Vivre sa vie is emblematic of cinema's capacity to move us to tears of joy and pain. It is symbolic of that love of classical cinema that the film itself both acknowledges and dismantles. I've come to see Nana's tears as a requiem for the bygone era of celluloid cinema and for the ineffable joy of opening up and letting it out, alone with others, in darkened rooms. For this reason alone, Vivre sa vie is, like every film Godard has ever made (even the less successful ones), worth watching time and time again.

– The Blu-ray –

The transfer on both this Blu-ray release is the result of a new restoration, and I quote, "using various restoration systems, removing dirt, scratches and warps, repairing damaged frames and improving stability isssues." The result is genuinely gorgeous, a beautifully detailed image with crisp 35mm sharpness and a luxuriously attractive tonal range, one that nails the black levels, has no high-end burn-outs and nails every step of the grayscale between. As that above-quoted description suggests, there's hardly a trace of dust or damage anywhere and the image sits rock solidly in frame. A fine layer of film grain is visible but does not appear tohave been subject to enhancement. A real standard bearer for HD restorations of films of this vintage.

The Linear PCM 2.0 mono soundtrack has some minor range restrictions typical of films from the pre-Dolby period but in other respects is also an excellent job. All traces of previous pops and damage have been cleaned up, next to no background hiss (important given the film's intermittent use of silence) and clarity on all sound is terrific throughout.

The English subtiles, too, are terrific and are very clear throughout.

When you select 'Play Film', you are offered the option to watch either the British or French theatrical release of the film. As far as I am aware, the cut of the film is the same in both cases, but on the British release the chapter title cards are in English rather than (optionally) subtitled French. The British version was recreated for this release by incorporating titles cards and intertitles from an original 35mm duplicating negative of that version held by the BFI National Archive.

Commentary

As if possession of this extraordinary film were not enough, the BFI re-release also comes complete with a master class in easy-going, well-informed commentary that would justify the purchase of DVD or Blu-ray in itself. The august Australian critic Adrian Martin provides an erudite audio-commentary on Vivre sa vie that is neither showy nor intimidating. Originally recorded as part of Madman Entertainments's 'Director's Suite' series for their DVD release of 2006, Martin's commentary also graced Criterion's 2010 U.S. DVD release of the film. Martin, who long ago established himself among the world's most perceptive commentators on cinema, has also provided audio-commentaries for Masculin Féminin, Deux ou trois choses que je sais d'elle, Le Gai Savoir, and Histoire(s) du cinéma as well as for classics like Ophüls' Le Plaisir and Lola Montès, Dreyer's Gertrude, Lang's Dr Marbuse, and Rossellin's Journey in Italy.

Among the many insights Martin offers, are those on significance of walls and windows in the film. Like Renoir before him, Martin says, Godard uses shots through windows as a means of intensifying tension and of reminding us that freedom lies outside and beyond the claustrophobic interiors. And "Nobody films walls the way Godard can." Martin describes how Godard commissioned Michel Legran to produce a complete musical score for the film but tellingly elected to use just ten bars of one variation. On the subject of voyeurism, he notes that we're always looking at Godard looking at Karina and that we're always watching that dynamic on three levels at once. He notes how Godard presses everything to hand into the service of his films: if you could smoke a cigarette, measure your height, or create an impromptu dance like Karina, he'd use it. If you could mime blowing up a balloon like Eric Schumberger, he'd use it. Godard doesn't miss a trick and nor, though there's nothing tricksy about his downhome delivery, does Adrian Martin.

Martin concludes with an exquistely elegant quote from the late, lamented Cuban-born U.S critic-cum-theorist Gilberto Perez. Perez says: "In this film, the song to Karina and the story of Nana have an alienation effect on each other. The song opens up possibilities that the grim story seems to foreclose, and the story brings up the difficulties the sweet song tends to disregard – these are the possibilities of love and freedom, the difficulties of power and prevailing circumstance. The lyricism of the film celebrates triumph, while the pathos laments the defeat of the soul that would gain embodiment, the freedom that would achieve realisation on the ground of recognised necessity."

Charlotte et Véronique ou Tous les garçons s'appellent Patrick (21 mins)

This slight but jaunty, gentle and charming 1957 short was Godard's first 35mm fiction film, Shot in and around the Jardin du Luxembourg, it tells the story of student flatmates Charlotte (Anne Colette) and Véronique (Nicole Berger) who are successively picked up by raffish boy-about-town Partrick (Jean-Claude Brialy). Produced by Pierre Braunberger and directed by Godard's from a script by Eric Rhomer, it is notable primarily for the legion cultural references that would become a Godardian trademark: the copies of Cahiers du cinéma and Hegel's Aesthetics we see, the posters of James Dean and Piccaso in the girls' flat, the copy of Arts magazine visible in a café scene (with its headline from Truffaut's article "The French Cinema is Dying Under False Legends), the "Mizoguchi-Kurosawa" one-liner Patrick uses on Charlotte. 'Real' life's there too: Véronique was the name of Godard's sister, Collet was Godard's girlfriend at the time, Berger was the producer's daughter.

Une Histoire d'eau (13 mins)

If Godard plays fast and loose with Eric Rohmer's script in Charlotte et Véronique, here he makes merry with footage of Jean-Claude Brialy and Caroline Dim (an ex-girlfriend of Godard's) shot by François Truffaut in the aftermath of a deluge that flooded the countryside around Paris. As in the earlier film, Godard makes a tight wee film at speed, on and out of next to nothing. The rudimentary plot of this 1958 short has a 'Girl' (Dim) picked up by a 'Man' (Brialy) as she tries to get to work in Paris. They fall in love along the way. It's full of references, of course: the title is a wordplay on Anne Desclos' erotic novella Histoire d'O and Aragon, Beaudelaire, Chandler, Franju, Goethe, Poe, Petrach are all cited. While Rhomer was displeased about the extensive revisions Godard made to his script, Truffaut was delighted with the use to which Godard put his raw material while he himself was otherwise engaged, making Les quatre cents coups. The voiceover is by Dim and Godard while, on this occasion, the snappy, sassy script is all Godard's work.

Charlotte et son Jules (14 mins)

Shot in Godard's Spartan hotel room on Rue de Rennes with film stock donated by Claude Chabrol, this comic bagatelle was envisaged as a gender-reversed homage to Jean Cocteau's Le Bel indifférent (1957) – the one-act play Cocteau wrote for Edith Piaf during the war. Orphée it ain't but it might have easily been titled La Belle et la Bête. Jean-Paul Belmondo's Jules is a self-centered misogynist who scolds and upbraids Anne Collette's Charlotte before weeping at losing her (he assumes she's returned to him but she's only popped back for her toothbrush). Jules is a writer who despises cinema almost as much as he despises his girlfriend: "You really want to go into the cinema. There's twelve thousand other blokes you're going to have to sleep with . . . What's the cinema? A big-head making grimaces in a small room. The cinema is an illusory art. The novel, painting, ok, but not the cinema. Everyone'll tell you you're nuts but you'll never listen. Result: you're the only girl in Paris who anybody can have for free." One of Jules' few noteworthy observations is: "Behind a woman's face, one sees her soul." Just as Truffaut had been detained making Les quatre cents coups, Belmondo was drafted for military service halfway through Chalotte et son Jules so Godard voiced his dialogue himself. As in the two earlier shorts, Pierre Braunberger (whom Godard would later call "a dirty jew") is the Producer and Michel Latouche is Director of Photography. Belmondo's character is called 'Jean' in this dry run for the bedroom scene in À bout de souffle in which he spars with Jean Seberg.

In Conversation: Anna Karina and Alistair Whyte (37 mins)

For those of us who've seen Godard's shorts several times and tired of their whimsy, this is the most interesting curio among the extras. Shot at and by the University of London Audio Visual Centre in 1973 shortly after Karina's now invisible debut feature, Vivre ensemble, was released, this riveting interview might have contained all the vivacity and vim of an Open University programme on molecular biology where not for the particular collisions between Whyte and Karina. Commenting on Karina's film in a long-overdue Top 100 list of films by female directors in the October issue of Sight & Sound, James Blackford describes Vivre ensemble as "a drama that tells the story of a hippy girl, Julia (Karina), and a rather uptight professor, Alain (Michel Lancelot)." During this interview a faint smile plays on the lips of the one serious-minded academic while the legendary actress seems always on the verge of a fit of giggles. Has Karina had a toke or is she bubbling over with amusement at the format and Whyte's O.U. style? I can't make it out, but, to be cruel, there's a fidgety, staccato hint of neurosis about Karina here. Whyte dares a comparison between Vivre ensemble and Karina's work with Godard, but the shutters come down when he attempts to probe her about her relationship with Godard. It's astonishing to realise how pronounced Karina's Danish accent is and how forthright she is in her dismissal of May 1968 as a storm in a teacup. Again, one doesn't have to be a psychoanalyst to discern her subconscious target when she talks of those who behaved dishonestly during that period. Fascinating fare.

Leslie Hardcastle Introduces Vivre sa Vie at the NFT (3 mins)

The joker in the pack. In this 1968 audio clip, Leslie Hardcastle, the esteemed Controller of the British Film Institute and the National Film Theatre, apologises to a packed house expecting to see Godard introduce Vivre sa vie as part of a John Player Lecture series. One can hear the smoke coming out of Hardcastle's ears as he describes the events leading to Godard's latest no-show. The booklet accompanying the BFI release informs us that about a hundred disgruntled punters accepted the BFI's offer of a refund while the rest remained seated to watch one of the most magnificent films ever made. The booklet also reproduces the telegram read out by Hardcastle in which Godard justifies his decision to stay at home: "WILL NOT COME TOMORROW. MOVIES HAVE NOTHING TO DO WITH CIGARETTES AND REALITY WITH SMOKE. YOUR UNKNOWN GODARD."

Also included is a Booklet containing a solid essay on the film by David Thompson (complete with spoiler warning), a perceptive contemporary review by John Russell Taylor (from Monthly Film Bulletin, February 1963), introductions to the short films by Virginia Sélavy, credits for the main feature and the shorts, details on the restoration, and a photo of the telegram sent by Godard to the BFI shortly before he was due to appear there in 1968.

Vivre sa vie may be the precisely composed of all Godard's films. It is as exciting, striking, haunting, thought provoking and influential as anything he has made to date. All the pieces fit. As Susan Sontag suggested, it may be the most perfect of this most gifted of directors' films. Time has not dimmed its luminous glow nor diminished its importance. It feels as fresh as if it were made yesterday. Karina is at her most radiant. Godard is at his most brilliant. A masterpiece of cinematic art by a towering giant of the form. Recommended, in the strongest possible terms.

|