|

– Part Two –

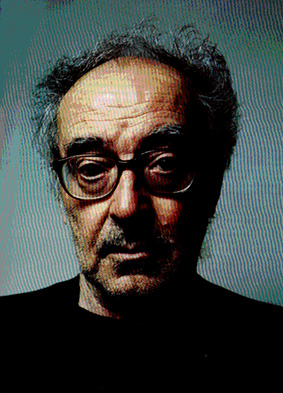

In Film After Film, critic J. Hoberman calls Godard "the first filmmaker to recognize that cinema's classical period was over." Godard was anticipating and precipitating that moment of rupture from as early as 1965: when Cahiers du cinéma asked him what he thought of the immediate and the long-term future of cinema, he replied, "I await the end of cinema with optimism." He prepared for it in the video-editing suite, which, as Jonathan Rosenbaum has argued, was, in a sense, the graveyard of cinema and of the history of the 20th Century. Having already re-invented cinema several times over, he catalogued the 'death' of cinema while inventing modern cinema. This is what Daney called "The Godard paradox": "He advances back-to-front, apprehensively, facing what he is leaving behind . . . caught between a recent past and a near future . . . doomed to the present."

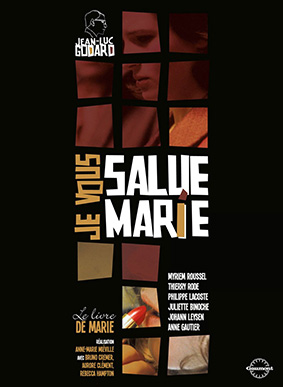

In an interview with Daney, Godard said: "People who love cinema today are like the Greeks who loved stories of Zeus . . . if they still like the idea of films on television, so shrunk, it is because there is still a vague memory . . . We no longer have our own identity, but if we turn on the television there is a small and distant signal which tells us that we may still have one. And someday, films will disappear from television too." Godard recognised that change was in the air and, as he had in the late sixites, he hastened change. Working mainly with his new partner Anne-Marie Miéville, from 1972 onwards he produced a series of experimental, politically analytical videos made primarily for television. Sadly, Godard's break with traditional cinema meant his work was inaccessible, even to film students desperate to explore his canon. So, it definitely felt as if Godard had emerged from hiding in the eighties when I watched Sauve qui peut (1980), Passion (1982), Prènom Carmen (1983), Je vous salue, Marie (1985), Détective (1985), and King Lear (1987).

It felt that way until the summer of 2001, when two events coincided that enabled me to view Godard's work (almost) in its entirety: the BFI's two-month long Godard retrospective (advertised under the rubric 'Jean-Luc Godard. Master of modern Cinema – A Definitive Tribute') and Tate Modern's 'For Ever Godard', an international conference addressed by Jean-Pierre Gorin as well as Godard aficionados such as Raymond Bellour, Richard Brody (author of the excellent Everything is Cinema: The Working Life of Jean-Luc Godard), Adrian Martin (whose commentary on Vivre sa vie enhances the BFI release), Colin MacCabe, Laura Mulvey, Jonathan Rosenbaum, and Peter Wollen, among many others.

During the retrospective and the conference, I saw many of Godard's video shorts for the first time and the continuities in his work emerged clearly. As an added bonus, the conference inspired the subsequent publication of For Ever Godard (Black Dog Publishing, 2004), a well designed, lavishly illustrated collection of erudite, scholarly essays. Godard's video films, in particular, came into to focus at that time. When he returned to the video-editing suite in the late eighties, all the skills and techniques he'd mastered in the seventies began to bear fruit, firstly in his epic masterpiece Histoire(s) du cinéma (1988-1998), and subsequently in Éloge de l'amour, Film Socialisme (2010), and, most recently, Adieu au langage.

Video afforded Godard independence, the opportunity to work from home, and new tools with which to make films and write about films. Nobody has embodied Alexander Astruc's notions of 'La caméra-stylo' more completely than Godard, and nowhere more so than in Histoire(s) du cinéma. A paean to and panegyric on cinema, the consolidation and concentration of all his hard-earned, profound knowledge about cinema, it is a dazzling, dizzying montage of sight and sound, feeling and thinking, a unique 'attempt at visual criticism'.

If Godard was reflecting on the passing of his century and his form, by implication he was also reflecting on his own passing, for he is enmeshed with and enshrined within those histories. At the time, he seemed like a lonely man in an empty cinema; a man adrift of our times and deserted by his mentors, his art form and his friends – Astruc, Bazin and Langlois left long ago, then Antonioni and Bergman left together, on the same day (30 July, 2007), Jean-Pierre Leaud went mad, Truffaut didn't even say goodbye . . . and so on. Godard seemed lonely and adrift then, he seems even more so now. That, I think, is why the tone of the late work is primarily melancholic and elegiac. Godard seemed to be saying goodbye to cinema and himself in Histoire(s) du cinema, and again in Adieu au langage.

Mercifully, neither Godard nor cinema are dead yet. As Michael Temple and James S. Williams said, prophetically, in the introductory chapter of their collection The Cinema Alone: Essays on the Work of Jean-Luc Godard 1985-2000: "It seems clear that cinema is barely emerging from 'the infancy of the art . . . Godard's project remains live and direct, unpredictably changing and always in search of fresh subjects and forms. His is an ingenuity of vision, a curiosity for the world. Isn't that also what cinema is, from before the cinematograph to those digital means and motifs which the future will soon outwit? . . . There is a long way to go. And Godard is still one of cinema's brightest hopes and promises for the new century."

Or as Daniel Morgan put it in the final sentence of his brilliant book Late Godard and the Possibilities of Cinema: "Still drawing on the history of cinema, but also creating new directions for its future, Godard continues his effort to discover and invent new possibilities for cinema." As Godard himself says in Bande à part, it is "better to carry on than to give up." So, we move on, always move on, as Godard has consistently done; in this instance, finally, to Vivre sa vie.

I have no grand theory about Vivre sa vie to offer, and there cannot remain much to say of a film that has been as extensively discussed as any in film history. I'll keep my remarks brief, therefore, and recommend the following close readings of the film that stand out from the crowd: Susan Sontag's 1964 review in Moviegoer,* Adrian's Martin's exemplary commentary on the Extras of the BFI re-release, the sections on the film in Richard Roud's Godard, the chapter on it that opens Kaja Silverman and Harun Farocki's Speaking about Godard, and Frieda Grafe's piece on it in the late, lamented Vertigo magazine.**

In the booklet accompanying the BFI re-release of Godard's fourth feature, critic David Thompson says: "It remains the most important film of Godard's career, the first in which he achieved a brilliant aesthetic blend of the worlds of documentary and fiction. It is also one of his most tender and moving, words not often associated with a cinema largely devoted to ideas and provocation." It is certainly one of Godard's most important films, representing as it does a decisive shift in his work and a turning point for cinema. The film's exquisitely composed tableaux and lengthy dialogue scenes revolutionised cinema. With Vivre sa vie, which won the Critics' and Jury Prizes at the Venice Film Festival, Godard established the talkies writ large and inaugurated a new, endlessly imitated discursive style.

Despite the explicit political content of Le petit soldat (1960), which was banned for many years in France, Vivre sa vie is not only Godard's most deliberately composted film but also his first step toward political cinema and the creation of a counter-cinema at odds with the values of orthodox cinema. It bears all the hallmarks of the radical oppositional style delineated by Peter Wollen in his essay on Godard in Readings and Writing: Semiotic Counter-Strategies: the fragmentation of narrative continuity, the disruption of traditional forms of emotional identification with characters, the foregrounding of language and the mechanics of filmmaking, the intertextuality and overspill, the rupture with 'entertainment' cinema that privileges the reality-reality principle over the pleasure-principle. It amounts to Godard's first frontal attack on the society of the spectacle.

Vivre sa vie: Film en douze tableaux, to give the film its full title, tells the story of Nana Kleinfrankenheim (Anna Karina), a single mother working in a record shop and struggling to pay her rent. When we first meet her she is giving her ex-lover, the father of her child, Paul (André S. Labarthe), the brush off. She longs to be an actress (like Anna Karina) but gradually slides into prostitution. She falls into the clutches of a pimp, Raoul (Sady Rebot) who ultimately sells her to other pimps, with tragic consequences. Despite her wretched circumstances, Nana finds short-lived happiness after falling in love with an unnamed 'young man' (Peter Kassovitz), in a pool hall. She wins his heart with one of the most joyous dance sequences in film history. In the same scene, an acquaintance of Raoul's, Luigi (Eric Schlumberger) relieves Anna's boredom by miming a child blowing up a balloon to the point it bursts. Although joy and humour burst out of Godard's films like fireworks, his pessimistic insistence on the impossibility of love precludes happy endings. We are denied one in Vivre sa vie: having begun with a loving close-up of Nana, the film ends with a close-up of her, as a corpse.

In this film of light and shade, walls and windows, Godard uses a single melodic refrain and recurring moments of silence to disrupt synchronicity. As he moves between the streets and boulevards of Paris and the hired hotel rooms and brothels where Nana's 'business' is conducted, he uses direct sound, recorded on a single tape, throughout. He also deploys debased Brechtianism and sub Satrean existentialism, an unwieldy seventy-pound Mitchell camera and quickfire interviews, the structure of the epistolary novel and the words of an official report. He cites Bresson and Zola, Dumas and Dreyer, Ophüls and Poe, Jean-Pierre Melville and Montaigne, Rossellini and Truffaut. Most significantly, he shoots Karina's flawless porcelain complexion and perfect ebony bob in close-up, from angles, from behind, in rising and fading black and white. There have been few more ravishing sights in cinema than Karina; Godard knew it and exploited her beauty to full effect.

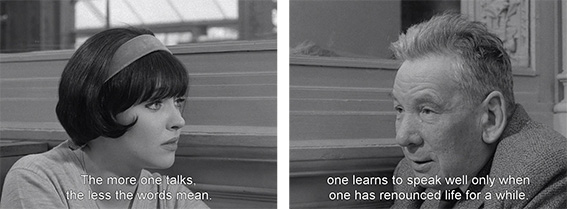

Susan Sontag called Vivre sa vie "one of the most extraordinary, beautiful, and original works of art that I know of," – and she knew a few. She objected to its ending but felt it was, otherwise, "a perfect film." She says: "It triumphs because it is intelligent, discreet, delicate to the touch. It both edifies and gives pleasure because it is about what is most important . . . the nature of humanity." In Sontag's opinion, Godard is "perhaps the only director today who is interested in 'philosophical' films and possesses an intelligence and discretion equal to the task." Here, Godard is ably abetted by philosopher Brice Parain. As Roland-Francois Lack notes in his useful A-Z primer on the film,*** Godard has Parain quoting from his book Black on White during a carefully edited 'conversation' with Nana/Karina ("We haven't yet found the means to live without speaking."). Conversation, Parain suggests, is a necessity of all human beings. We are social animals so we must communicate, but in order to do so we must move, as Vivre sa vie does, from speech into silence and back again.

In the opening scene of Vivre sa vie we find Nana and Paul in a bar, talking. Initially, we see only their collars and the backs of their heads. According to Adrian Martin, critic V.F. Perkins described Vivre sa vie as "a series of propositions about how to film a conversation." If that is so, those propositions were sound. Parain paraphrases Alexander Dumas' story Twenty Years Later, in which the Musketeer Portos plants a bomb in a cellar, thinks for the first time in his life, stops in his tracks, and subsequently dies beneath a pile of rubble. To live fully, to talk and think clearly, is to put oneself at risk. Parain says, "Error is necessary to truth." Godard, like Renoir and Rossellini, constantly reinvents himself and his form because he's always prepared to risk error in search of cinematic truth. With the help of his preternaturally gifted cinematographer, Raoul Coutard, Godard drove cinema forward to new levels of verisimilitude by flouting pre-existent conventions of filming conversations. Despite the switch from the light, portable Caméflex Éclair camera of his first feature to the weighty, unwieldy Mitchell, we feel we're hovering on Nana and Paul's shoulders, eavesdropping. This feeling of intimacy and proximity recurs throughout the film and is one of the many 'documentary' qualities that, along with the tragic narrative and Karina's magnificent acting, make it so moving.

In the film, Paul is played by Cahiers critic André S. Labarthe, who went on to make a series of exemplary documentaries on important directors for the Cinéastes de notre temps series he established with Janine Bazin in 1963. Labarthe filmed Godard in conversation with Fritz Lang for the series shortly after the two men had finished working together on Le mépris. In the resulting film, Le dinosaur et le bébé, Godard and Lang discuss the great pioneers of silent cinema. Lang says: "Almost no one from that time when we started out is still with us." Godard interjects: "There's Dreyer, Abel Gance, and you." They agree that Gance's Napoléon (1927), Dreyer's La Passion de Jeanne d'Arc (1928), and Lang's own M (1931) stand out as imperishable works of art also capable of appealing to mass audiences. Fortunately, Godard is still with us, and we can add Vivre sa vie to that hallowed number: it was one of Godard's few commercial successes (if only due to its tiny 400,000 franc budget) and received widespread, if not unanimous praise.

Watching a Godard film is a little like unpeeling an onion; it may soothe as well as sting the eyes, but it reveals layer upon layer of meaning the closer one gets to its core. We must always untie the Gordian knot of Godardian references, cross-references, and references within references to penetrate to the heart of his multi-layered, multivalent work. The naming of Nana, for example, is at the root of a characteristic cornucopia of citations. It reveals the debt the film owes to Zola's Nana (his novel of 1880 that also features a prostitute who meets a sticky end), to Jean Renoir's Nana (1926), and to silent cinema. As is often noted 'Nana' is an 'Anna-gram', alerting us to various director-muse/director-star relationships, most notably Renoir's relationship with Catherine Hessling (née Andrée Madelaine Heuschling), which prefigures Godard's relationship with Anna Karina (née Hanne Karin Bayer). Coincidentally, Pierre Braunberger produced not only Vivre sa vie but also both Renoir's Nana and his short silent film Charleston Parade (1926). As if to highlight the dubious sexual politics of Vivre sa vie, the latter short can be seen as a documentary on the director's wife avant la lettre: Hessling spends most of that film dancing, semi-naked, for the benefit of a gorilla and a time-travelling black and white minstrel. In Godard's case, Karina plays a prostitute, which disturbingly makes Godard both her client and her pimp. We'll come to that soon.

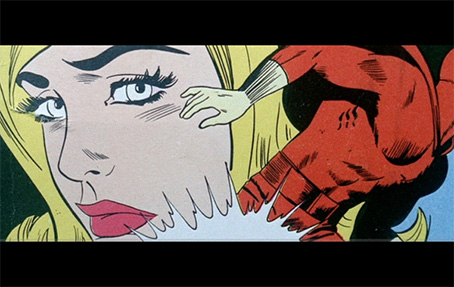

Prostitution, literal and figurative, is, of course, a recurring theme in Godard's work. Most obviously, it's embodied by Anna Karina in Vivre sa vie, Marina Vlady in Deux ou trois choses, and Isabelle Huppert in Sauve qui peut, but it's there, too, in Le mépris (the writer who prostitutes his talent), in Une femme mariée (marriage as legalised prostitution), in Alphaville (dystopian-state-sponsored-prostitution), and so on. For Godard, we're all trapped in the cash nexus; advertising is a form of prostitution that moulds us all; we work, clock off, and then begin working again, for the industries of the night. The Frank Tashlin he loved most was the Tashlin of Will Success Spoil Rock Hunter? (1957) – a barbed satire on Madison Avenue ad men that spoke to Godard's contempt for American consumer capitalism . In Vivre sa vie, though, that contempt is muted and there are still traces in the film of the love of Americana and Hollywood that underpinned the Cahiers critics' politique des auteurs position.

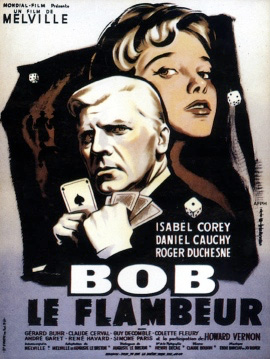

The film is dedicated to B-movies and its grand finale is straight out of a Hollywood gangster flick. Fittingly, it was filmed around the corner from Jean-Pierre Melville's suburban studios and replicates a scene, shot on exactly the same spot, in Melville's Bob le flambeur (1956). In a sense, it is fitting, too, that the ostentatious American car (a Ford Galaxie Sunliner) driven by the pimps who kill Nana was actually one of Melville's own: Melville was a witness at Godard and Karina's wedding, but it was he who had introduced Godard to the brothels and striptease clubs of Paris in the fifties. The trailer for Melville's film announces: "From the nightclubs of Pigalle to Deauville's 'private' rooms, everyone knows Bob." Although Godard and Melville had bonded around a shared cinephilia and pronounced passion for Hollywood as well as similarly pecuniary lecherous habits, they fell out over Vivre sa vie. In Everything is Cinema, Richard Brody notes that Melville's widow, Florence, remembered Melville saying to Godard: "You are making a lazy man's cinema . . . you put down the camera and you have people talk, nothing more. For me this isn't cinema."

Melville wasn't the only one to take against the film's formal innovations. As Richard Brody again reports, Roberto Rossellini, whom Godard revered, was equally unimpressed. In late 1962, when screenwriter Jean Gruault brought Rossellini to a screening of Vivre sa vie, the Italian reprimanded the Frenchman for having "made him waste his time." Gruault recounts the conversation he overheard the following day when Godard drove Rossellini to Orly airport: "On the road to the airport, [Rossellini] maintained a silence that was heavy with danger. Suddenly he proclaimed, in a deep, prophetic voice, like that of Cassandra announcing the fall of Troy or Isaiah threatening an impious people with the gravest harm: 'Jean-Luc, you are on the verge of Antonioni-ism!' The insult was such that the unfortunate Godard lost control of the car for an instant and almost sent into the landscape." This incident, in addition to giving another meaning to the idea of cinema as matter of life and death, reflected Rossellini's discomfort with what he saw as Godard's imitation of Antonioni's arid formalism and tendency to trap his characters in a prison of inescapable alienation, specifically by denying Nana agency and presenting her descent into prostitution as inevitable and inexplicable.

Vivre sa vie was not, of course, either the first or last word on prostitutes or prostitution in cinema. Anna Karina's Nana send us back to Louis Brooks in Pabst's Pandora's Box (1929) and Greta Garbo in Clarence Brown's Anna Christie (1930) while anticipating Shirley MacLaine in Wilder's Irma la douce (1963) and Catherine Deneuve in Buñuel's Belle de jour (1967). Godard's interest in prostitution as a theme, which would intensify with his politicisation, may have been precipitated by evenings spent with Jean-Pierre Melville but it primarily arose from his bibliophilia and cinephilia, specifically from his admiration of Guy de Maupassant and Max Ophüls.

Two Ophüls' films, in particular, left their mark on Godard: Le Plaisir (1952) and Lola Montès (1955). While promoting Vivre sa vie, he made repeated references to the latter. "Nana," Godard said, "like Lola Montes, is able to safeguard her soul while selling her body." Elsewhere, he seems to predict and forestall Rossellini's criticism: "Nana does not pervert herself, she just accepts what comes – whatever happens she continues to exist (like in the Lola Montès song). What interests me is how her situation is the result of the world around her; how her freedom is tied to the freedom of others."

Godard defied bourgeois hypocrisy and male chauvinism (sins of which he himself was guility) when he called Ophüls' Le Plaisir "the greatest French film made since the Liberation." The influence of Ophüls magisterial adaptation of three short stories by Guy de Mauppasant is evident in the nonjudgemental way Godard treats prostitution in Vivre sa vie. There can be no doubt that Godard was emboldened by Ophüls' daring approach to the subject of prostitution. In La Ronde (1950), the first film Ophüls made after his return to Europe after working in Hollywood during the war, Simon Signoret plays Leocadie, a street-walking prostitute ordered by the master of ceremonies to proposition the sixth soldier who comes her way. The third part of Le Plaisir, his follow-up to the hugely successful La Ronde, features a rejected lover who cripples herself in a suicide attempt. Astonishingly when one considers the repressive mores of that period, Ophüls had intended to tell the story of a young man who drowns himself after his girlfriend is seduced by lesbians. Sadly, the producers of the film weren't as progressive as Ophüls.

As Roland-François Lack says, the comment that opens tableau 10 ("There's no gaiety in happiness") is a direct quote from Le Plaisir. In the central story, La Maison Tellier, the sailors of a port town and its local male bourgeoisie go into shock when the local brothel temporarily closes to enable the women who work there to attend a rural first communion. The women are shown to be intelligent and vivacious. They insist on their right to live their lives as they see fit. They lend themselves to others but give themselves to themselves. [The film, incidentally, stars Simone Simon, who had earlier appeared in Robert Wise's Mademoiselle Fifi (1944) – which itself amalgamates two other Maupassant stories concerning prostitutes: Mademoiselle Fifi and Boule de Suif (1945) – with the latter being the source text not only for Christian Jacque's Boule de suif (1945) but also for John Ford's Stagecoach (1939)].

In addition to the influence of Maupassant, Melville, Ophüls and Renoir, the figure of Bresson looms large. Discussing Vivre sa vie in Contintental Film Review, Godard said: "I've a great admiration for Bresson. I hope in a way that Vivre sa vie is for the prostitute what Pickpocket (1959) was to the world of the thief. But while Bresson probes the interior, I want to express the interior by revealing the exterior behavior. I show the everyday details of Nana's existence because I want the spectator to understand why she follows this evolution (into prostitution)." The famous scene in which Nana watches Dreyer's La Passion de Jeanne d'Arc in a cinema was initially intended to feature excerpts from Bresson's Le Procès de Jeanne d'Arc (1962). He had Bresson's permission and the extracts lined-up, but changed his mind at the last minute.

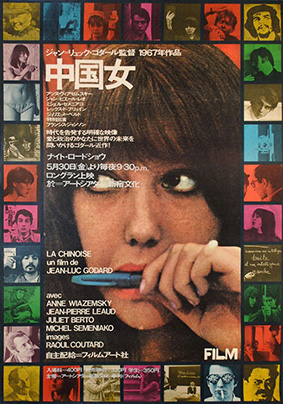

Godard's decision to use Dreyer's film instead was a good call. The close-ups of Karina replicate Dreyer's close-ups of Falconetti; the parallels between two women at the mercy of men, interrogated by men, and ultimately killed by them is clearer in Dreyer's film; and, anyway, Dreyer's version is far superior. Bresson was as important to Godard as Dryer, in life as in films. It was Bresson who introduced him to his next 'Anna': Godard and his second wife, Anne Wiazemsky, first met on the set of Bresson's Au hasard, Balthazar (1966), which Godard would famously described as "The world in an hour and a half." Wiazemsky subsequently appeared in several Godard films, which sit between art and life and are built from both.

Life and art are inseparable in Godard's work because for him cinema is life. Without the chance to film, he was like a little boy lost. Interviewed by Michel Vianey during the shooting of Pierrot le fou, Godard said: "If I shoot films, it's because I'm alone. I have no family. Nobody. It's a means of seeing people. Of going places." It is that deep need to make films and his interrelated insistence on the real that makes Godard tick. In Jean-Luc Godard (Editions Seghers, 1963), the first book on the director, Jean Collet suggests that the key to Godard's work lies in the interplay of documentary and fiction. "My starting point is documentary," Godard said, "to which I try to give the truth of fiction."

Of course, Godard's starting point was documentary in a literal sense: he began with Opération Béton and made his breakthrough with À bout de souffle – of which Raoul Coutard said: "Producer Georges de Beauregard told Jean-Luc he had to work with me. I was cheap and Godard was determined this was going to be the cheapest film ever made, shooting in the street, with no sound, no lights, no crew. He told me it would be like shooting a reportage."

In the opening sequence of the film, Paul tells Nana a story written by one of his father's pupils: "A bird is an animal with an inside and an outside. Remove the outside, there's the inside. Remove the inside and you see the soul." "How can you render the inside?" asked Godard during an interview about Vivre sa vie, before replying "Precisely by staying prudently outside." Godard could tell a story when he wanted to. He just generally chose not to. The film alternates between documentary and fiction while Anna moves between being in possession of herself and at the disposal of others. Tableau 8 is taken up by a verbatim reading from Judge Marcel Sacotte's report, Où en est la prostitution? Nana/Karina writes a letter applying for work as a prostitute, copying verbatim the text of a sample letter in Sacotte's survey.

The film, then, is a story with a beginning, middle, and end, in that order, but opens with a documentary of a face (one of the most beautiful, photogenic faces ever to grace the screen), has a documentary on prostitution at its centre, and ends with a documentary on the collapse of a marriage. Cahiers du cinéma described Une Femme et une femme, as a documentary on Anna Karina. Vivre sa vie is another one. It is, I think, impossible to fully understand the film without reference to Godard's relationship with Karina.

*Susan Sontag's review (Moviegoer, No. 2, Summer/Autumn 1964):

https://kirkbrideplan.files.wordpress.com/2012/08/66307739-godard-s-vivre-sa-vie-sontag-1964-120copy.pdf

**Frieda Grafe on Vivre as vie (Vertigo magazine, Issue30, Spring 2012):

https://www.closeupfilmcentre.com/vertigo_magazine/issue-30-spring-2012-godard-is/jean-luc-godard-vivre-sa-vie/

***Roland-François Lack's Vivre sa vie: An Introduction and A-Z:

http://sensesofcinema.com/2008/before-the-revolution/vivre-sa-vie-a-to-z/

|