|

– Part One –

| |

"Jean-Luc Godard is not the only director for whom filming is like breathing, but he's the one who breathes best. He is rapid like Rossellini, sly like Sacha Guitry, musical like Orson Wells, simple like Pagnol, wounded like Nicholas Ray, effective like Hitchcock, profound like Bergman, and insolent like nobody else." |

| |

François Truffaut, 1966 |

| |

"Sprawl is the quality/of the man who cut down his Rolls Royce/into a farm utility truck, and sprawl/is what the company lacked when it made its repeated efforts to buy the vehicle back and repair its image . . . Sprawl occurs in art . . . Sprawl gets up the nose of many people/(every kind that comes in kinds) whose future does not include it . . . Sprawl leans on things/It is loose-limbed in its mind/ Reprimanded and dismissed/it listens with a grin and a boot on the rail/of possibility." |

|

Les Murray, from The Quality of Sprawl, 1986 |

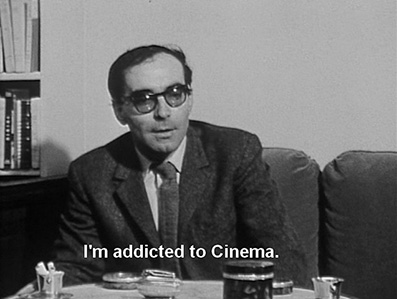

In 2011, Bernardo Bertolucci was awarded the rare honour of an Honorary Palme D'Or at Cannes. Half a century earlier, he had stood beside Richard Roud, who was director of the London Film Festival at the time, as he tremulously awaited an introduction to Jean-Luc Godard. Bertolucci's awed reaction to meeting Godard for the first time was identical to that of the great French critic Serge Daney: he vomited. I fully understand that response. Others, perhaps perplexed by Godard's elliptical style or irked by his political and philosophical discursiveness, may understand it for different reasons. We walk (gingerly at times) in the footsteps of giants and for many of us Godard, for all his myriad character flaws and contradictions, is the one who stands tallest; the keeper of film's flame; cinema's archivist, educator, inventor, philosopher and historian sans pareil; simply the most daring and exciting, passionate and poetic, ingenious and important artist of the modern age working in any form.

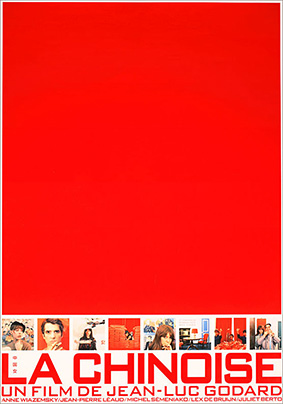

Ever since his first film, Opération Béton (1955) – a 17 minute-long short about the construction of the Grand-Dixence dam, Godard has also been among the most prolific of directors. In 1967, the BFI published Godard, Richard Roud's monogram on the Franco-Swiss visionary. The first English language book on Godard and the first in Sight & Sound's seminal 'Cinema One' series, it traced Godard's development from his first shorts through to his fourteenth feature, La Chinoise, an extraordinary film that prefigured, even to an extent precipitated the events of May 1968. In an appendix on that film, which was still being completed as his book went to press, Roud says: "No book on Godard can hope to be up to date for long; no other important director makes as many films a year as he. All the more reason, however, I thought, to try to make this one up to date for at least a month or two after its publication." Soon after Roud wrote those words, the portmanteau film Loin du Viêtnam appeared (featuring Godard's contribution, titled Caméra-oeil in homage to Dziga Vertov), and then Weekend were released. In the same period, Godard was shooting L'amour, his segment of the Italian anthology film Vangelo 70. Godard has made over a hundred films since then.

For obvious reasons, Godard was particularly productive in the period following the collapse of his marriage to Anna Karina, but he never stopped making films. His extraordinary productivity is one of many reasons he is also among the most discussed of directors. There is a lot to discuss. And to discuss Godard is, still, to take sides. Few directors have divided opinion as sharply he has: where some see a playful profundity, others see pretentious prolixity, others again see an intoxicating, often irritating admixture of both; where some see a succession of astonishing films equally successful in their own terms, others see a bafflingly overrated body of work punctuated by failures, and others see an understandably uneven oeuvre marked by discernible continuities. Godard even divides his admirers: some find his accessible early films dazzlingly successful, others prefer his 'political' films, others again regard his later experiments in video and 3-D as the best of his vast output.

Godard's admirers will hope he is still making films at 103, as the late Manoel de Oliveira was, and that he continues to interrogate the world at large, and audio-visual culture in particular, with his characteristic vigour and invention. Those annoyed by his politics and philosophy, his contradictions and intransigence may wish Godard would just drop dead. Gerturde Stein famously described Ezra Pound as "a village explainer, excellent if you were a village, but if you were not, not." Godard is, among other things an explainer of and for the global village of cinephiles. It is easy to see why those poor souls living beyond our boundaries do not always share our enthusiasm for Godard. Much online coverage of film is derisively referred to as 'fan' content, as if enthusiasm were a weakness not a virtue. I make no apologies for declaring my passionately partisan predilection for Godard.

To illustrate the divergent opinions that crystallize around Godard, I'll begin by scratching an itch on a long-healed wound. My jaw dropped and my pulse quickened, earlier this year, when I clicked on 'Perfect! Let's Do It Again', a boldly provocative article on this site, in which 'Camus', our 'unofficial Hollywood correspondent', considered great directors and what makes them great. It was New Year's Day and the disorientating after-effects of bacchanalian excess intensified as I absorbed his engaging thoughts. The period we make merry with lists was still upon us and he duly obliged with a 'Top Ten' of Bergman, Fellini, Ford, Hitchcock, Kubrik, Kurosawa, Ray, Renoir, Welles and Wilder. I momentarily wondered whether he meant Nicholas or Sajit Ray, weighed In a Lonely Place against The Apu Trilogy, and then instinctively reacted by reaching for Godard – Godard and Antonioni, Bresson, Dreyer, Eisenstein, Gance, Resnais, Tarkovsky, Vertov and Visconti. To my huge relief, my colleague granted Andrew Sarris space to flesh out the pantheon with another ten canonical names. Take a bow Chaplin, Flaherty, Griffith, Hawks, Keaton, Lang, Lubitsch, Murnau, Ophüls and von Sternberg. He also shoehorned in a nod to Scorsese and a wink to Truffaut. By then, I'd revised my first thoughts and plumped, instead, for Cassavetes, Chytilová, Erice, Jennings, Marker, Pialat, Pasolini, Pudovkin, Rossellini ("one cannot live without Rossellini") and Vláčil. The names fell fast, randomly, sometimes alliteratively, occasionally associatively, as I worked my way through the alphabet or the revered masters of cinema.

My mind was bursting with names. It nearly exploded when my colleague asserted that no living director could make the cut. "You cannot," he wrote, "be great and still be alive (time is the first judge of greatness)." Again, I screamed out -"'Godard! Godard for fuck's sake!" – before selecting ten alive and kicking also- greats who've stood time's test: Bertolucci, Hou Hsiao-Hsien, Kaurismäki, Kiarostami, Kieślowski, Sissako, Sukarov, Tarr, Varda and Wadja. I then blushed and hurriedly added Akerman, Clarke, Deren, Holland, Ramsey, Reichardt, Reiniger, Shepitko, Shub and von Trotta. The front cover of Sight & Sound's October issue announces a special feature, The Female Gaze, which contains a list, spread over twenty pages, of "100 overlooked films directed by women." In the same issue, Marc Cousins throws his weight behind this long-overdue act of reclamation. He argues against the assumption that partriachy successfully excluded female directors. "Luckily," he says, "there are lot's of people - researchers, curators, festivals, publications - who, now and for years, have been naming and celebrating the great female directors from the past." All of which goes to show how blinkered the lists I offer above are, how shamefully sexist as well as Eurocentric I am, how nonsensical lists (particularly lists of ten) are; and what irresistible, useful fun lists are too. The critics' lists appall and enthrall me in equal measure. Lists are a double-edged sword, they are two-faced: they are both the enemy of criticism and its lifeblood, they force us to think while thinking for us, they consolidate the idea of a canon while seeming to confront it, they guide us towards films while steering us away from them. Although I appreciate a canon of 'greats' is an accretion of persuasive reviews and, yes, lists, I still baulk at the way critical consensus marginalizes often more interesting work.

My colleague ended with ten moderns of his own and concluded by inviting us to let him know if he'd missed anyone "really obvious (we're talking about directors with a significant body of quality work, men and women all agreed by most critics and commentators to be in possession of a unique voice)." Godard! Godard for fuck's sake, I screamed, and Apitchaptong, Ceylan, Davies, Diaz, Guzmán, Haneke, Mekas, Olmi, Wenders and Zvyagintsev. The list may not be endless but it's always incomplete. Is it all, though, as he suggested, all merely a matter of opinion? In How to Read Literature, Terry Eagleton provides a ready-made repost to the argument that criticism can only ever be subjective. "Whether you prefer peaches to pears is a question of taste," he says, "which is not true of whether you think Dostoevsky a more accomplished novelist than John Grisham. Dostoevsky is better than Grisham in the sense that Tiger Woods is a better golfer than Lady Gaga." Godard is a more accomplished filmmaker than (pick a name, any name), let's say, Spielberg, in the sense that Gina Rowlands was a better actor than, oh, I don't know, Muffin the Mule.

If few remain neutral about Godard it's partly because he represents a certain way of making and thinking about films; a certain tendency in European cinema earthed in the iconoclasm of the avant-garde, shaped by the politics of the anti-Fascist European left, aspiring to art, unashamed of philosophy, and defiantly at odds with Hollywood. In his views on Hollywood, as in many other senses, Godard's career can been seen as a lurching from extreme to another. He fought his first battles with the 'Hitchcocko-Hawksians' of Cahiers du cinéma as they rallied to the flag of Hollywood and then defended it against the enormous condescension of European film critics during the politique des auteurs period. Later, the arch anti-Americanism of Le mépris (1963) and Bande à part (1963), which had already intensified with Made in USA (1966) and Deux ou trois choses que je sais d'elle (1967), gradually hardened into virulent disgust. His attitude towards American cultural imperialism and Hollywood is now expressed through a narrative of European resistance and American occupation.

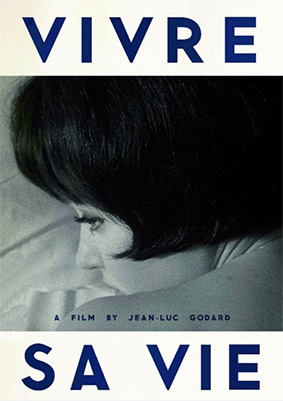

Despite or because of that stance, Godard still has legions of admirers on both sides of the Atlantic. At 85, he bestrides two competing cultures like a colossus. His latest film, Adieu au langage (2014), a typically daring experiment in DIY 3-D, was unlikely either to win an Oscar or find favour with mainstream audiences but it won both the Jury Prize at Cannes and the U.S. National Film Critics award. Given Godard's stature, the scale of his achievements, and my profound respect for him, my stomach tightens at the mere thought even of offering these few short thoughts on him. In the preface to his indispensible biography Godard: A Portrait of the Artist at 70, Colin MacCabe says: "In its range of reference – the history of cinema, the history of art, the history of Marxism – the work is as daunting as the life. It would be a fool who thought they had all the necessary competencies to comment fully on this extraordinarily rich œuvre." I'm no such fool, not least because, a decade and half after the release of MacCabe's book, the challenge is larger than ever. The BFI's dual-format release of a newly restored, pristine print of Vivre sa vie (1962) may not, offer much that is new (the BFI themselves released a new print of the film in 2004), but it does present an irresistible opportunity not only to consider one of the most influential films of its era but also to think out loud about Godard and his incomparable, sprawling, inevitably uneven, enviably vast body of work.

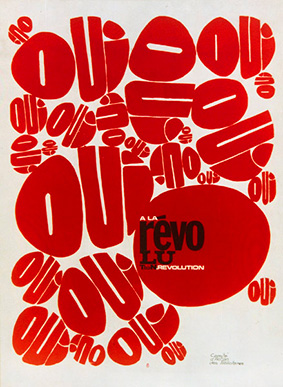

What drew me and continues to draw me to Godard? What is it in his work that profoundly moves me? His restless fecundity and ferocious intelligence but perhaps above all, his sly, sharp wit and contrarian cheek. It's funny to think that the thing I love most about Godard might be his elusive, acerbic sense of humour. There's something anarchic and impish in him that corresponds to what Australian poet Les Murray called "The quality of sprawl" – that fiercely independent, rudely democratic Larrikin impulse Murray detected in the outback outlook; something tinged with the spirit of May 1968 and the Maquis but also oddly reminiscent of the anti-authoritarian humour glimpsed in certain Ealing films. For a generally dark, deadly serious director Godard can be very funny.

To pick up the strand of Godard's anti-Americanism again, there's the exhilarating and hilarious scene in Bande à part in which Godard has the three musketeers Claude Brasseur, Sammy Frey, and Anna Karina race through the Louvre in an attempt to beat the speed record set by American tourists. There's the use to which Godard puts TWA and PAN AM flight bags in Deux ou trois choses. There's Belmondo's deadpan, impatient "My name is Ferdinand" in Pierrot le fou. Or the scene in which Belmondo 'bumps into' Jeanne Moreau in a bar in Une Femme est une femme and asks her "How's it going with Jules et Jim?" There's the scene in Éloge de l'amour (2001) in which two women dressed in the folk costume of Brittany canvass signatures for a petition to dub The Matrix (1999) into Breton.

Then again, there's the scene in Le mépris, shot at the legendary Cinecittà studios, in which a European director (Fritz Lang 'as himself') clashes with a philistine Yank producer (Jack Palance as Jerry Prokosch). It tickles me pink when Prokosch hurls a can of celluloid across the screening room as if he were a Greek Olympian hurling a discus. And it always makes me laugh when Lang vainly attempts to explain the adaptation of The Odyssey they're working on. Prokosch asks: "Now what great stuff are we seeing today Fritz?" Lang says: "Each picture should have a definite point of view Jerry . . . here it's the fight of the individual against circumstances. The eternal problem of the old Greeks." To which the American derisively snorts, "Oh, please!"

If Godard's sense of humour passes many people by, it may be because it doesn't announce itself with crashing cymbals and a roll of drums; it seeps, silently and subtly, out of his seriousness. Running alongside the humour, there's Godard's depth of knowledge, his reach and range, his poetics and politics of citation. In a moment characteristic of the cultural layering at play in Godard's work that same scene in Le mépris is reprised, to equally hilarious satiric effect, in Éloge de l'amour. As James Quant (Senior Programmer for the increasingly important Toronto International Film Festival) says: "In both films, European myth, history, and culture are sold, plundered, and falsified by an American producer." Godard, of course, has always 'plundered' American and European culture at will himself, while looking both ways, sometimes three ways at once. For example, Éloge de l'amour also reworks Otto Preminger's Bonjour Tristesse (1958) and, therefore, À bout de souffle (1960), which reworked the American's film first.

Morality and Tracking Shots |

|

Even if Godard doesn't, as his old Cahiers comrade Luc Moullet claims, always read books whole but, rather, "pecks at books like a hen in the garden," he is the ultimate cultural magpie. He has appropriated material from his contemporaries as well as from literary, philosophical, and cinematic sources, but tends to bend, amend and transform quotations. Witness his inversion of Moullet's claim that "Morality is a question of tracking shots": Godard's oft-quoted aphorism that "Tracking shots are a question of morality" adds aesthetic and political bite to a reactionary phrase initially suggesting that tracking shots are all morality consists of. Godard's work has been compared to Walter Benjamin's unfinished magnus opus The Arcades Project, which was envisaged as a comprehensive, compendious survey of Paris in the 19th century built entirely of quotations that would converse and interact with one another, igniting an almost endless number of associative chain reactions. Godard's work operates that way. Taken as a whole, it is as wide reaching, spacious and monumental as anything in cinema.

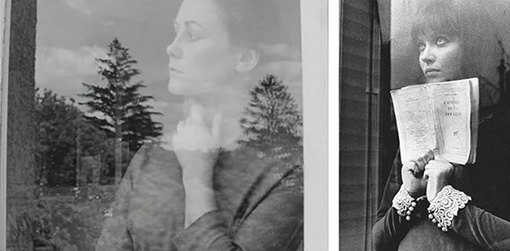

Daunted as I am at the prospect of reviewing a Godard film, I'll continue to edge, nervously, toward the task, on safe ground and home turf, by delineating my lifelong relationship with his work. Initially, my intense personal connection to Godard was exclusively emotional and hormonal. An adolescent crush on Charlotte Brontë was, I confess, superseded by a teenage infatuation with Anna Karina. Even as that limited ardour cooled slightly, Godard's early films, so suffused with the energy and excitement of youth, slipped deep into my bloodstream like amphetamine. I was hooked as soon as I saw À bout de souffle, which sat alongside Colin McInnes's Absolute Beginners, Jack Kerouac's On the Road, and J.D. Salinger's Catcher in the Rye among the sacred objects of adolescence and the symbols of several generations' rites of passage into adulthood.

The adrenaline rush of my teenage encounters with Godard returns each time I watch Vivre sa vie, Band à part, Une femme est femme (1961) and Masculin/Feminin (1966). For me back then, these were films of Swinging Paris as surely as Blow Up (1966) was a film of Swinging London. All are now like love songs carried on the breeze, bearing with them memories of naïve dreams and teenage kicks. The charge those stylish, irreverent films transmitted was bound up with a love of mod culture inseparable from a deepening cinephilia that was itself inseparable from Francophilia. Just as the 'young Turks' of Cahiers du cinéma had championed Hollywood's finest as a reaction against the moribund, stultifying cinéma de papa or cinéma de qualité, so the young punks of my university days rallied to Godard and the European New Waves as an alternative to increasingly repulsive and formulaic mainstream Hollywood films and a fusty, generally reactionary British film culture.

Growing up, it seemed to me in my late teens, meant coming to prefer, better say, claiming to prefer Alphaville (1965), Pierrot le fou (1965), Made in USA (1966), Deux ou trois choses que je sais d'elle (1967), and Weekend (1967) to the superficially slighter early films, though the depth of those films only revealed itself gradually. Interestingly, Anna Karina says in No. 13 of Faber & Faber's 'Projections series, "The young people I meet at film festivals tell me their favourites are Vivre sa vie or Une femme est une femme, but mostly Pierrot le fou. In England and Brazil they love Alphaville, and in Germany they prefer Une femme est une femme." Uhm.

As the buds of my mind opened, I deserted Literature for Film, after belatedly realising, halfway through my degree, that I could actually study Godard. And as I explored his work he hastened my politicisation, even shaped my worldview, to the same extent reading Orwell (another formative influence) did. As with Orwell, the more I learned of the man, the less I liked him; the more I learned of the work, the more I respected him as an 'artist'. I was surprised to find marked similarities between Orwell and Godard: both worked from a deep-seated European suspicion of American culture and power; both were outspoken socialists, critics of the status quo, fearless in presenting unpleasant truths, and eloquent proselytizers for their respective forms and politics. There were similarities in their personalities too: both men, for instance, surmounted their early misogyny and both were initially unsuccessful serial mariage proposers. Of course, while Orwell lacked Godard's sense of humour, he more than made up for it in other ways. Godard, for his part, stretched his form to breaking point. His long-since co-opted co-option of genres, his encyclopaedic cultural references, his political insight and idiocy, his entire extraordinary work pointed me in extracurricular directions of which most of my tutors seemed to have scant knowledge. Godard taught me in ways they didn't.

And when I eventually watched the films of Godard's 'militant' or 'Maoist' phase (the Dziga Vertov/Sonimage period when he worked primarily with Jean-Pierre Gorin), I did so with a new kind of excitement, as an ardent convert to the old-fashioned idea that money isn't everything and as one persuaded that humankind faced a stark choice between socialism and barbarism. This was in the eighties – a period when, as I saw it, folk had begun to give high-sounding names to sordid instincts. As a grasping love of money was elevated to the highest social virtue and the iron fist of monetarism began battering communities to death, films like One Plus One (1968), Vent d'est (1969), British Sounds (1969), Lotte in Italia (1970), Vladimir et Rosa (1971), and Tout va bien (1972) struck a different chord with me. They chimed with my rising anger. They offered an alternative narrative about the catastrophic changes unfolding before my very eyes, a refuge from the depredations of neo-liberalism and the piles of human misery on which Thatcher's Britain were built.

If I sensed the futility of a retreat into the past, I think I reasoned that, as someone once said, withdrawal in disgust isn't the same as apathy. And anyway, hadn't Godard himself retreated from political realities? That's the million-dollar question. It might be argued that he has been in hiding since the seventies; initially, because confronted by the dead-end of Maoism, recoiling from the shock of shattered dreams, perhaps embarrassed by things said at the height of the fighting; later, increasingly hermetic as a sense of alienation from and generalised revulsion at the world set in. Godard paid a heavy price for the loss of audience his urge to invention entailed: a collapse into individual subjectivity characterised by meditative melancholia and elegiac interiority. He often seems like a devoted mediaeval anchorite who has withdrawn to a cell (in Rolle), communicating his religious fervour for cinema, and his findings on it, to the outside world through a thin slit in the wall of distribution. In Je vous salue, Marie (1985), a woman called Eva, asks a professor what he's thinking. He might be speaking for Godard when he replies: "I think politics, today, must be the voice of horror."

Then there's Serge Daney's argument that "There has never been anything revolutionary about Godard, rather he is more interested in radical reformism . . . His own utopia is to demand that people open themselves up to the possibility of doing things 'differently' even while continuing as before. This utopia is less about doing something different than about doing the same things, differently."

Daney has a point. There was an air of adventurism and exhibitionism in Godard's revolutionary posturings and pronouncements. He continued to travel first-class, literally and metaphorically, throughout his Maoist phase. Jean-Pierre Gorin's description of himself as "the Yoko Ono of cinema" logically makes Godard 'the John Lennon of cinema', and it could be argued that Godard's politics were always more Lennonist than Leninist (even, or especially around May 1968). Not for nothing did Truffaut call his estranged mate "the Ursula Andress of militancy," and not for nothing did he suggest that Godard's autobiography be called "A Shit is a Shit."

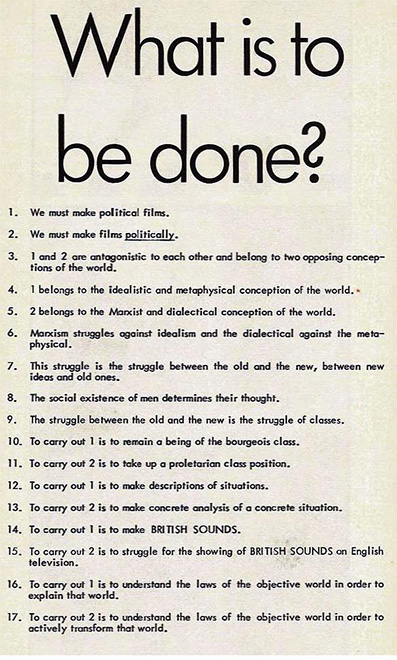

It might equally be argued, against Daney and Truffaut, that the sincerity of Godard's politics and his revolutionary impulses are evident in every film he's ever made. Although he seemed to vanish after the political possibilities of May 1968 were contained, and although he moved from France to Switzerland (first to Grenoble and then Rolle), he continued his investigations into politics and the politics of the image, just in new forms incompatible with conventional methods of film production and distribution. His apparent disappearance enabled him to pursue 'politics by other means'. It could be viewed as a sane response to an insane world and to his own dictum that the challenge for radical filmmakers was not to make political films but to make films politically.

|