|

Videodrome is a film that made a serious impact on two of the writers on this site. I can guage this by the memory of the first VHS video letter that Camus sent me, many years ago, which he opened with a recreation of the film's main title, done I believe on a Commodore 64 (more on that later), having filmed the screen and created the film's brief picture break-up by jiggling the connection between computer and monitor. Thus to avoid having to engage in potentially lethal telekinetic battle, Camus and I agreed to share the coverage of this one.

However, my friend has always been quicker off the bat than me and thus had his half of the review completed and in my inbox before I'd even started on mine. On top of that, in his enthusiasm he had written what I would class as a complete review, and in the process made many of the things I was planning to say redundant. I've thus restricted myself to picking up a few things that he has not covered in detail, a few additional points and a personal reaction to a film that has been part of me since the first time I saw it. The bulk of my work has thus been the coverage of the extra features included with Arrow's Limited Edition Blu-ray and DVD package, of which there are many. And so, to business.

Note that there are some major spoilers ahead for newcomers. When we start talking plot (that's the third paragraph of Camus's review), you might want to skip ahead to the next paragraph.

| Videodrome review by Camus |

|

| |

"My imagination is not full of horrors at all. This is the misunderstanding of what my movies are. First of all, I think all my movies are funny. Not everything in them is funny, but they are full of humour. And second, it's not really my imagination. Anybody looking at the news on the internet or in a newspaper, there's horrors there every day – compared with that, my imagination is a wonderful playground!" |

| |

Director/Writer, David Cronenberg,

Guardian Interview, 14 September 2014 |

| |

"A Clockwork Orange for the 80s..." |

| |

Andy Warhol on Videodrome |

But then Warhol was probably biased, being a friend of a certain Debbie Harry of Blondie fame at the time. Harry is Videodrome's leading lady and what a brave performance she turns in. More on that a little later.

In 1983, I was at the desperately young and almost professionally callow age of twenty-two. Along came Mr. Cronenberg to put me straight. And by straight I mean remind me of the world beyond straight, a world where the rules are exquisitely twisted and smashed, where sensuality possesses a much keener edge over morality, where pain dances deliriously close to midnight inching inexorably into the heady suncrow and cockrise of pleasure. In short, this Canadian auteur from whose work I had shied away – it was simply too nasty for my innocent imagination – had presented me with a choice; embrace the idea of different, perverse and dangerous or close the door with a line of solder and never darken it again. It's true, cinematically speaking, I've led much more of a vanilla eXistenZ than most (sorry, my ship hit the 'Cronen' berg there). I've not bravely pursued a multicoloured, multifaceted life of dangerous hedonism but that doesn't mean the door of my daring is always shut. I once stayed up until gone midnight. I was very familiar with Cronenberg's oeuvre up until 1983, having read The Shape of Rage, but had only actually seen Scanners and The Brood. In the filmmaker's nascent period, the BBC's regular TV film critic at the time, Barry Norman, gave a beyond scathing review of Shivers which put a spoke in my wheel of potential appreciation. These days, offended negativity from this safe, mainstream cricket-mad broadcaster would tempt me more than any million dollar marketing. It's enough to know that this other world is there beyond what's acceptable and that it's populated by an distinctive swathe of human beings whose aberrant behaviour and diverse emotional responses would turn society inside out like Billy's shunting opponent in the movie that bears such an innocuous and ironically exclusive name. So I applaud this film not for its significance (though it has plenty), neither for its emotional resonance (the darker ones are present and deliriously incorrect) or its fear factor (there is major near-knuckle – and some through the knuckle – content). I celebrate Videodrome because it taught me that cinema was infinitely kaleidoscopic and that which sat (or lurked) outside my comfort zone should be more readily, nay, enthusiastically tasted. After each of the lurid Rick Baker creations has spurted its last, what're left are ideas and to be frank (with no disrespect to film directors everywhere) ideas are where the seeds are nurtured, grow and blossom. Oh, and there's a semi-naked Debbie Harry in the movie too. I know, but I am of that age and this would have been a draw, a known (and comforting) element in a film that was almost guaranteed to scare the a, c and bejesus out of me. For those who cry "Foul!" at the very idea that a woman's sex appeal would be something to attract an audience (the deuce you say), rest assured that James Woods is also naked in the same scene. But then he never sung 'Heart of Glass' or 'Call Me' in such a beguiling way.

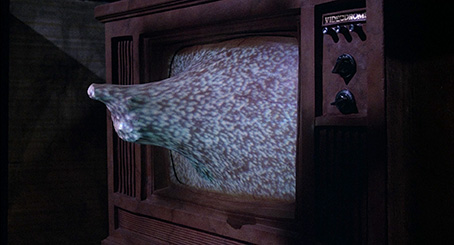

Woods plays a Civic TV executive, Max Renn, a man content to drag net the scummier depths of the market. Cronenberg usually creates such wonderful character names but this one is a simple inversion of the Renn Max motorcycle, something Cronenberg was obsessed with at the time. Max runs this two-bit satellite channel in Toronto. Played on a constant, nervous knife-edge by Woods, Renn is a sleaze ball with ambition. The actor has built in angst. He's not a romantic lead in the standard mold but he can carry a film and does so here with some aplomb. Even at rest, he gives the impression of being five coffees to the wind. In fact, he's perfectly cast here, right down to the studied and expert flippancy and lack of pretence as he chats up Debbie Harry on live TV. We have to plant Videodrome defiantly in the 80s. There's no getting away from that fact. There is an argument for the timelessness of the film's ideas and premise but the props and milieu are inserted and fixed within the pure, sticky amber of the VHS/Betamax era. God knows how a film of a similar genetic make-up would work in the digital age. But there is definitely one to be made. Max leads the life of a hedonistic executive burning more dark person hours and candle ends in the pursuit of televisual treats that will snare the lowest common denominators. Soft-core porn has had its decades in the sun bleached, dirty-pool L.A. apartments. Max then stumbles upon what seems to be a pirated channel originating from the exotic climes of Malaysia served up by his tech underling, Harlan. You get a strong sense that A Serbian Film is destined to play on this illegal signal named 'Videodrome', animatronics and all... But then A Serbian Film is fiction...

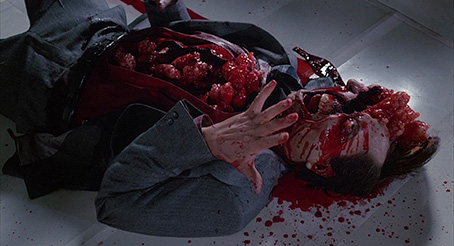

Videodrome's offerings are just beyond hardcore and for all the world, and all the souls in it, it's real horror. Have we reached that line and gleefully or morbidly crossed it? Videodrome is torture porn for real, snuff TV (or is it?), horribly hypnotic and literally cancerous. In no time, Max starts seeing things that cannot be there (or can they? I'll stop this now and strongly resist the urge to add "Or will I?" Damn). Once the hallucinations kick and settle in, he changes not subtly into a man with a monomaniacal, murderous mission. This is the evangelist's worst nightmare. In creating a way to control and subvert the base instincts of a depraved television audience and let's not forget wipe them out with tumours, Max has been brought into being, a man with a zeal of disapproval. He is to wipe out those in charge of Civic TV – a more hostile takeover it's hard to imagine. And he has his sights mirrored back on to those who have appointed themselves moral attack dogs. This flea bites back. I find it doubly funny that the bad guys in Videodrome could be headed by a Blofeld-like Mary Whitehouse, the righteous anti-smut campaigner in the 80s who would no doubt have topped herself faced with the Cnut-style job of halting the deluge of unsavoury content on the world wide web. OK, 'Canute' if you must but I had a little frisson putting those four letters in a sentence containing the words 'Mary' and 'Whitehouse'. The company fronting Videodrome, Spectacular Optical, is headed by a smarmy Barry Convex played by Les Carlson. His crusade is to weed out and expunge those who enjoy more base entertainment. That would be one hell of a scourge. Who would be left? Antique Roadshow viewers? No disrespect to Game of Thrones (I watch it for the intrigue!) but there's a good commercial reason for the inclusion of nudity, sex and horrific violence. As more sophisticated animals we no longer need to act on our base survival programming (we have supermarkets) so outlets are provided to satisfy that terrible primal hunger (or so the argument goes). I think this is facile to a degree but I'll admit that there is something satisfying in seeing a horrific character get his violent comeuppance. To be honest, I think Joffrey got off lightly. Poison? Schmoison.

Videodrome is a film falling over itself with intelligence and references to, let's say, a whole library of related academic content. Yes, it's wrapped up in a ribbon of body horror and viscera that should not dent its smarts. Videodrome put the muck into McLuhan and it's a more intriguing work for just that reason. Why shouldn't intelligence get down and dirty? It's been living in sterile-world for far too long. What the movie has to say and infer about the media is so on target, the felt of the bull's eye has been pierced away leaving a huge clump of dart feathers sticking out like a mallard's rear end. As I write, the Labour leadership is in turmoil as a true Leftie rises in in-party popularity. Many regard him as being nationally unelectable. Except that both these 'facts' are simply not true. The 'truth' is largely unknown to most people and has myriad facets. Print truth is balloon skin, newspaper inflation. The media's favourite game is Chinese Whispers. A source makes a remark, broadsheets magnify and lay columns of discourse and opinion onto its single ethereal brick of foundation and before you know it, the media is making the news it thinks it's simply reporting. The perfect recent example is the hounding and shaming of scientist Tim Hunt whose only 'crime' was to make an ironic joke that out of context managed to derail the man's whole life. Newspapers cannot build in context or perspective. For one, their truth is literally black and white and two, their reporters have no time to add depth to any story. Read Flat Earth News for elaboration on this topic. The internet has also enforced the context-less power of the media in another form. People can be wrongly named or shamed in the past but these days, you can tweet ironically, get on a plane and by the time you've landed, your life is over. Seems dramatic? Google Justine Sacco... The only thing I've believed in the past week is that a certain ex-PM has made himself even more of a below the belt related expletive than I thought possible. The media more than most governments control the slow drip or front-page splash of agenda. Let's face it, Milliband was destroyed by a snap of him eating a sandwich. The foreseeable proliferation of the world wide web has made Max's practical world redundant. We don't require cumbersome tapes and clunky decks to port our desires anymore. Like electricity, we just have to jack ourselves in. That said, our reliance on the screen and its content has never been more palpable.

A whole generation and more are being raised in a screen age, an era of multi-connectivity that in the inevitable irony of human life, represents a level of practical and physical disconnection we've not 'enjoyed' since the horse still reigned supreme as our principal method of transport. Yes, we have hundreds or thousands of followers. How many of those would be at your side in an emergency? We're going to have to start redefining human relationships and (in another irony) realise that as our digital avatars surround themselves with scores of 'friends', our true friendships have suddenly increased in worth and relevance. In the world of Max Renn, it's clear he still has many appreciated personal relationships. His assistant Bridey (Julie Khaner), the first uncomprehending witness to a violent hallucination, is faithful, loyal and rightly concerned. Even under Videodrome's homicidal influence, Max still manages to throw her a 'What can I do?' look as he makes his escape from his own office block. Before Max has a startling epiphany, his trusty pirate of the airwaves, Harlan (Peter Dvorsky), is doing nothing but favours for the man he calls (one assumes with sly, ironic affection) 'patrone'. There's Debbie Harry of course, playing the beautiful and seductive Nicki Brand. Harry's bravery to jump in at the deeper, less clothed end in her first real starring role is something to be admired. Harry's ease on screen playing scenes that experienced actors may not have pulled off convincingly always impresses. How does she make it seem so convincing to burn her breast with a cigarette end (and enjoy it?). Even James Woods flinches as anyone would. And yet, from a list of the top female actors working in the 80s, I can't name too many who could have pulled this role off as well as Harry did. She's using Max as a route to self-fulfilment so despite her usefulness to Max's short-term sexual and burgeoning sado-masochistic well being, she's a transitory object or even a transitional one, easing the path for Max to slip into the dark, immersive lobster pot. In many ways Nicki's the personification of Videodrome, the 'new flesh'...

The relationship that strikes me as the one Max loses at his peril is the one with Masha (Lynne Gorman). A mother figure desperate for a son's approval, she's trying to offload a soft porn TV series (think I, Claudius with even more nudity) with which Max is utterly unimpressed. The further down the cold, dark line Max travels, the more concerned Masha becomes. It's Masha who clues Max to the figures behind Videodrome and it's her influence beyond the hallucinations that starts Max down the path of illumination. She is, to be flippant, Max's Obi Wan and they're both facing a physiological and psychological Death Star, a whole world of hurt. When Max is confronted by the one question no one wants to answer (why watch something as nasty and scummy as Videodrome?) his evasion ("Business reasons,") is as amusing as all of those who claimed to read Playboy for the interviews or watch Game of Thrones for the intrigue. But then I stand by that particular admission. Max has been hoist by his own id, seduced into being a pawn in a larger game, infected with an electronic worm that will not die or stop burrowing. But worms can turn...

Writer/director Cronenberg explains very little (a sincere thank you, Mr. C.). We are left with interpreting Max's actions for ourselves and trying to figure out what's demonstrably 'real' in the context of the mise-en-scene and what's only in Max's mind. It's when his surreal psychosis kicks up impossible images, images that appear to have real world 'reality', does the movie jolt (and not in a bad way). If a character is killed by means of impossible events, how do we interpret this death? There seems to be no doubt of the fatality itself but there's no clue to how the actual death was caused 'in reality' but then if we are completely in Max's mind throughout the last act, then these surreal and extraordinary acts of violence are rightly self-contained. The ending, though fitting and evolutionary on its own terms, always struck me as – how can I put this – not entirely joyous. It's not like I expected the movie to provide answers but given how many topics it thrusts in the audience's face for further exploration and debate, the actual film ends unequivocally. To me the movie was a springboard. It's sobering to launch yourself into space and suddenly realise that no one's filled the pool.

I want to end on covering two notable aspects of the production. Famed Lord of the Rings composer, fellow Canadian Howard Shore, has worked with Cronenberg since the start of both men's careers. In fact he enjoys as rich a creative relationship with the filmmaker as John Williams does with Steven Spielberg. Like the Williams/Spielberg partnership, Shore has only missed scoring one of Cronenberg's movies (The Dead Zone) to date. His work on Videodrome is unsettling and insistent. Low frequency synthesizers (very much a product of the 80s) pepper the movie with portent. There is no theme per se but on my most recent viewing I was surprised how memorable the score was despite its simplicity. Secondly, there's the 'novelization'... No word should give a true connoisseur of the arts more reason to shudder. After the novelization of The Omen made a small fortune on its own in 1976, movie studios found they had lucked into another source of revenue. Stories, which did not belong in the universe as books, became hack-written novels based on original screenplays. There were very few quality exceptions. Videodrome was my first. Not only was the novelization of Cronenberg's early script superbly rendered into a novel that could stand on its own, it also included initial ideas that never made it into the movie. Here, you have a dovetail experience where the book and movie compliment each other. I'd quote from it but after a house move, my books are still in storage. It surprises me that the book is available at vastly inflated prices online. Its artistic success may also be down to the fact that Cronenberg took the idea of a Videodrome novel very seriously. It may say written by 'Jack Martin' on the cover but this is a pseudonym for horror novelist Dennis Etchison and a Stephen King endorsed success in his own right. Cronenberg worked closely with Etchison to ensure the quality of the associated novel. And it really shows. Great. Just when it's not available to hand, I really want to read it again...

Videodrome is on the surface a horror/science fiction thriller with at its core a metaphorical take on what harm an addiction to extreme screen immorality and horror may bring. Under the surface (it's darker down here but warmer, better conditions for growth) the movie asks questions that are more relevant now than any time in human history. Does voyeuristic consumption of death, torture and rape change us positively, negatively or at all? Media guru Marshall McLuhan's answer to that may surprise you. Does the act of watching move us further away from real physical human contact? Does our primal self crave such 'pleasure' and if so, what harm is it doing? Roll up, roll up, ladies and gentlemen... I give you Videodrome. Long live the new flesh...

| Videodrome additional by Slarek |

|

The strongest memory I have of my first viewing of Videodrome was emerging from the cinema feeling like I'd taken the sort of psychotropic drug that the government currently seems obsessed with trying to outlaw. Like Eraserhead and Altered States before it, and Primer some years later, the film had seriously messed with my head, but as with the aforementioned drugs, it did so in an exciting and supremely satisfying way. As I stumbled to the pub with my equally fazed companions, I found myself suffering a degree of reality disassociation, caught in a dream bubble with a translucent membrane that was floating a few centimetres above the ground. Alcohol failed to clarify much, but the discussion that followed was lively and littered with theories about what had unfolded before our eyes and ears over the previous 90 minutes.

I saw the film again when it was released on video, and as soon as I could afford do so I bought myself a copy. When Criterion released it on a well-featured DVD in the US, I bought that too. You could say I have a thing about the film, one that had burrowed into my psyche and spread through me like a virus. It didn't make complete sense on that first viewing but I seemed to understand it and over time all became clear, and when it did so I found myself having to re-evaluate my initial reading of the characters and story, particularly Nicki. Here's a question for those who've seen the film (skip ahead to the next paragraph if you haven't): at what point did you think Nicki became a hallucination? More to the point, was she ever real? That's something that would never have occurred to me on my first or even second viewing, but which later seemed an obvious thing to ask. Oh man, I love it when cinema makes you question what you've seen, then question it again and still want to go back and look for more clues.

Camus makes a solid case for Deborah Harry's contribution to the film, but I do feel the need to hammer home the strength of James Woods' performance, which I believe is central to why the film works as well as it does. He may now be known as much for his right-wing politics as his acting (his Twitter feed consists mainly of cheering on Republicans and bashing anyone he deems 'liberal' – yikes), but during his formative film acting years Woods delivered some of the most compelling performances of the period, his lean looks, forceful intensity and almost impatient twitchiness making him a consistently arresting screen presence. It's easy to forget that Videodrome was early film-career Woods, just four years after his breakthrough role in Harold Becker's The Onion Field and a year before he joined a mother of an ensemble cast in Sergio Leone's Once Upon a Time in America. Videodrome showcases the actor at his Salvador best, as he energises every line of dialogue and peppers his portrayal with small bits of business that pull Max off the screen and make him feel like someone you know personally. And crucially for the film, Woods plays every aspect of Max's predicament with unwavering conviction, in the process selling even the most mind-bending elements of his deteriorating condition as real. This is particularly evident in his reaction shots: the sharp intake of breath when he drops the 'living' video cassette; his wince at the sight of Nicki stubbing out a cigarette on her breast; his startled confusion at the vaginal opening that appears on his abdomen; the desperation as he searches frantically for the gun that cannot, surely, have been absorbed by his body. And it never feels overplayed or 'performed'. Watch the film for Woods' performance alone and you'll get more than enough from it to justify the entrance fee.

And he's not alone. There's not a wrong note in performance anywhere in the film, with even the smallest roles cast with care and sincerely played. It helps that they're given such great material to work with. More than once in the extra features, crew members state that the script was one of the best they'd ever read, something repeatedly evident in the carefully crafted dialogue and thoughtful intelligence of the ideas being proposed, discussed and developed. In this respect, Videodrome represents a turning point for the director, his most successful melding to that date of character-based storytelling and art-house intellectualism, and the point at which all of the elements explored in his previous films came harmoniously together, in the process offering the clearest pointer yet to the direction his career was to later take.

Whether the film is trying to have its cake and eat it when it comes to one of its underlying themes is a question that cropped up in a number of contemporary reviews, and remains one about which I am uncertain (second spoiler alert). A direct reading would suggest that the film is targeting those conservative moralists who would like to restrict what we watch and who dream of unleashing a potentially lethal punishment on those who do not share their puritan views. Yet by smuggling the Videodrome signal in a broadcast that consists of nothing by sadism and violence and showing its effects to be so toxic, the film also could be seen as siding with those who maintain that violent imagery in films is genuinely harmful to the viewer and that exposure to it is likely to inflict serious and lasting psychological damage. Given Cronenberg's own oft-repeated opposition to censorship and dismissal of the idea that film violence alone can trigger psychotic behaviour (a view I happen to share), I can't imagine this was his intention, but it still offers up interesting food for thought. After all, if Videodrome the in-film transmission can damage its viewer, could Videodrome the film in which that signal is contained do likewise? Oh, we could have fun with this.

What caught me out a little bit is just how well Videodrome has stood the test of time and how contemporary much of it feels. And it really shouldn't. Its technology has been lost to the past and should have dated it badly, but so strong and forward thinking are its ideas, so compelling is its drama, and so accomplished is it both as art and entertainment, that none of that matters. Indeed, given Cronenberg's fascination with the very physical factors of flesh and mutation, if feels only right that the medium of the Videodrome signal's delivery should be equally tactile. This physicality is something we're losing as everything goes digital, and while there may be a degree of nostalgia attached to that statement, in cinematic terms, a typewriter is more visually and aurally interesting than an iPad, a record player more tangible than iTunes, and a video tape more evocative of purpose than a USB stick. That doesn't mean to say that there isn't potential in a digitally induced mutation because there is – just read a few William Gibson stories to get you started. But it all just works here. Videodrome remains a unique work because no other bugger has even tried to emulate it. It's quite possibly the peak of Cronenberg's superb early genre work, but also sets a style and tone template for the films that would follow. It's also, in my humble opinion, the director's first genuinely great film.

The 1.85:1 transfer sports a restoration undertaken by the Criterion Collection for its 2010 Blu-ray release, and was carried out under the supervision of cinematographer Mark Irwin and director David Cronenberg. While it doesn't pop in the manner of some of Arrow's own in-house restorations, this is partly down to the film's deliberately dour look – interiors are often gloomy and prime colours are rare, and despite a couple of bright sky exteriors, it's genuinely hard to imagine the sun ever shining on the Toronto in in which Videodrome is set. But the detail is crisp and far superior to even Criterion's DVD edition (check out the complex decor in Bianca O'Blivion's office), the colour is naturalistic, and while the contrast may seem a little strong at times, pulling detail into the deep black shadows, the extras confirm that this was always Irwin's intention. Dust spots and damage are almost non-existent, the image is very stable, and a fine layer of film grain is visible. Nice one.

The Linear PCM mono 2.0 soundtrack, also restored by Criterion, is in excellent shape, with clear rendition of the dialogue and effects and a startlingly good dynamic range for a mono track, with solid bass on the beep throbs of Howard Shore's electronic score and none of the treble bias you find on many older mono tracks.

Optional subtitles for the deaf and hearing impaired are also included.

| extra features – disc 1 by Slarek |

|

This new limited edition release from Arrow is loaded with extra features spread over two Blu-ray discs. The second contains four of Cronenberg's early short films, my coverage of which here has been partially adapted from an earlier review of the later two films. But first, disc 1. Are you ready for this?

The first collection is located under the banner Documentaries and Featurettes:

Cinema of the Extreme (21:04)

Originally broadcast by the BBC in 1997, this documentary by Nick Freand Jones explores Cronenberg's cinema, censorship and the horror genre, and includes contributions from Cronenberg, George Romero and Alex Cox, whose BBC series showcasing key works of cult cinema was titled Moviedrome, of course. As you would expect, given that the full title is David Cronenberg and the Cinema of the Extreme, Cronenberg is the key contributor here and is as thoughtful and persuasive in his arguments as ever, particularly when analysing his own work or discussing his opposition to censorship. Cox convincingly argues that that if a film can make you feel genuinely disturbed or uneasy then that's quite an achievement, then makes a bit of a tit of himself by complaining that Se7en, a film that meets that criteria perfectly, was disgusting, perverse and not entertaining at all. Seriously? Possibly my favourite quote comes from the ever-upbeat George Romero when he says: "The biggest problem that I've always had with horror is that things are always restored to normality in the end, whereas the whole genre is meant to bring down reality or destroy it." Absolutely. Being a product of the TV of the time, the framing is 4:3., but it's in good shape.

Forging the New Flesh (27:44)

A 2004 documentary on effects work on Videodrome, directed, edited and presented by Michael Lennick, the special video effects supervisor on the film. Comprised mostly of archive footage captured during the shoot, it's peppered with short interviews from the time and new ones filmed specifically for this documentary with members of the effects team – Rick Baker included – and location manager David Coatsworth. For fans of the film it's invaluable stuff, with details on how specific effects were achieved, a horror story about working with week-old sheep guts, and even brief footage of Cronenberg directing James Woods during Max's first meeting with Harlan. Everyone appears to have been impressed by the script – makeup effects man Bill Sturgeon describes it as the best he's ever read – and Rick Baker reveals that after seeing Cronenberg's early films he expected him to look like Peter Lorre. This one is also framed 4:3.

Fear on Film (25:40)

A hugely enjoyable round table discussion from 1982, hosted by Mick Garris and featuring David Cronenberg, John Carpenter and John Landis, all of whom have proved themselves to be excellent ambassadors for this once maligned genre. The issue of ratings and censorship throws up some interesting stories, as does a discussion on preview screenings, and all three discuss their own past movies. Cronenberg and Carpenter also talk about their current projects, which happen to be Videodrome and The Thing, the second of which Landis cannot wait to see. Landis also reveals that he once had a golden rule that bloodletting cannot be funny, until he saw he dismembering scene in Monty Python and the Holy Grail, which he thought was hysterical.

Samurai Dreams (4:47)

The complete and uncensored footage shot for the extract of the Japanese softcore porn show Samurai Dreams that Max considers buying, including front-end colours bars and the episode title (in English and Japanese – nice touch), with commentary by the special video effects supervisor Michael Lennick. Times have changed and this is hardly boundary busting stuff now, but considering that what was used of this scene was subject to some censorship on its initial release, there would likely have been some seriously raised eyebrows and further cuts enforced had the whole thing been included. Lennick's commentary provides some useful technical background, and he ends by describing the whole thing, without a hint of the grin that must have crossed his face, as "A wonderful production we are all deeply proud of."

Helmet Camera Test (4:45)

A number of tests for the shot which show Max's viewpoint of Nicki through the helmet camera, each with a different digital video effect applied, and we're talking old school DVE effects here, done by running NTSC video through a video mixing bench (I've still got one of these). On the soundtrack Michael Lennick once again provides the technical details of how this was achieved, which I personally found enthralling. But that's me.

Why Betamax? (1:11)

Michael Lennick is again on hand to reveal that the true reason for selecting Betamax as the video format of choice for Videodrome was not its famed technical superiority over VHS, but the fact that VHS cassettes were just a bit too large to comfortably push into the opening on Max's abdomen.

Promotional Featurette (7:52)

An EPK made during the film's production, produced and directed by Mick Garris, in which interviews with Cronenberg, James Woods, Deborah Harry and Rick Baker are blended with always welcome behind-the-scenes footage. Some of the material also mades an appearance in the Forging the Flesh documentary detailed above, but there is more of everything here.

Commentary by Tim Lucas

As tends to be his way, author and Video Watchdog founder and editor Tim Lucas delivers an interesting if dryly delivered commentary on the film as if reading from a prepared script, which he may well have been, of course. Fortunately much of what he says is absolutely worth hearing – when writing for Cinefantastique he was the only reporter on set, where he interviewed key personnel and observed much of the filming. There are thus plenty of personal recollections of the shoot, plus detail on the locations, the actors, and how some of the special effects were achieved (although you’ll find much more on this in the preceding documentaries). Occasionally I had the feeling he was getting a little Room 237 on some of the details, but this is balanced out by the things he highlights that you might otherwise have missed.

The next three features are under the banner Interviews:

Videoblivion: An Interview with Mark Irwin (26:27)

Cronenberg's once regular DoP Mark Irwin enthrallingly reveals how he became a cinematographer and the path that eventually led him to work for Cronenberg (whose early films he had studied at film school) on the too often sidelined Fast Company. Their subsequent work together is also explored, with particular emphasis on Videodrome, the technical and artistic approach and challenges of which he covers in fascinating detail. Hats off to animator Michael Heagle for so accurately reproducing the words 'Arrow Films' in the style of the Civic TV logo at the start of the film, and to cameraman Dean Azim for lighting and framing the interview in a manner that I'd like to think Irwin himself would be pleased with. A first class extra.

Pierre David on Videodrome (10:20)

Videodrome, Scanners and The Brood executive producer Pierre David (how nice that despite having been involved in over 150 productions, he's listed on IMDb first as the producer of this movie) reflects on a film whose production went like clockwork and but which died at the box office, the absolute opposite of his experience on Scanners, the making of which was – I'm using his words here – the most dysfunctional he's ever been through, but resulted in a monumental hit. That Videodrome finally caught fire on home video tends to justify his belief that it was ahead of its time.

a.k.a. Jack Martin with author Dennis Etchison (16:45)

The author of the novelisation of Videodrome – which is covered above by Camus – recalls landing his first job of this sort adapting John Carpenter's The Fog, which as a fan of science fiction, the then recent independent horror boom and Carpenter in particular, he jumped at. This led to other adaptations for Carpenter and eventually the invitation to adapt Videodrome for David Cronenberg, whose work he also deeply admired. Etchison takes us through some of the challenges he faced reworking such a visually oriented film for the printed page, and the difficulty of telling the story entirely from Max's viewpoint. He also cheerfully states that he could never cut it as a hack screenwriter because he could not write with enthusiasm and passion about something he thought was dumb. Sir, we salute you.

The last three extras on disc 1 are located on the main extras menu:

Camera (6:42)

A short film written and directed by Cronenberg in 2000 to mark the 25th Anniversary of the Toronto Film Festival, it stars former Cronenberg regular Leslie Carlson (he plays Barry Convex in Videodrome) as a faded actor who sits in his kitchen and agitatedly recalls an occasion when his children brought home an old movie camera, an object whose function he links with ageing and death. As he talks, a group of young kids wheel a Panavision camera and associated professional film equipment into the house and prepare to shoot an interview with the storyteller. In what feels very much like an aesthetic dig, this monologue is shot hand-held on digital video and is peppered with uncomfortable close-ups, unflattering angles and burned out highlights, but when the man begins his story again for the young camera crew, he is more pleasingly framed on 35mm in a carefully composed and visually seductive dolly shot, and the tone of his delivery has become warmly nostalgic. An utterly enchanting and touching piece.

Pirated Signals: The Lost Broadcast (25:47)

When the film was prepared for American TV screening, several significant changes were made, including the inclusion of material removed from the director-approved theatrical cut. Most of these extend existing scenes, sometimes revealingly but also occasionally overstating what works better when left just a little ambiguous. There's even a replacement scene for Max's limo ride to meet Barry Convex at Spectacular Optical – in the film he travels alone, but here he rides and converses with Nicki. Also included is a very different opening title sequence and an end-of-film recap of key lines of dialogue. That the spectacular conference death scene has been cut to the bone is hardly surprising, given that it was also trimmed for its initial cinema release. Framed 4:3, the clips appear to have been sourced from a medium resolution tape original.

Trailers (4:35)

Three trailers for the film, the second of which is a seriously trippy animation that makes no attempt to capture the tone of the film and was apparently created almost solely on an 8-bit Commodore 64 (younger readers can check out season 2 of Halt and Catch Fire, where this much loved machine has a featured role). The third combines this with live action clips and appears to end of one of the themes from Michael Mann's Thief.

Booklet

Okay, I know it's not a disc 1 extra, but it had to go somewhere and disc 2 is all about Cronenberg's early films, so this is thus where it sits. A typically handsome document, it includes sizeable extracts from the Faber and Faber book Cronenberg on Cronenberg (which I'd heartily recommend to anyone interested in the director's work), in which he discusses his early films and their making in some detail. This is followed by a compelling essay on these very works by Caelum Vatnsdal, filmmaker and author of They Came From Within: A History of Canadian Horror Cinema. The quality doesn't drop with a fine essay on Videodrome by Justin Humphreys, plus another large chunk from Cronenberg on Cronenberg in which the director talks about Videodrome, its making, its sexual politics, and the problems it ran into on completion. After this is a really useful article by Brad Stevens on the cuts made to the film by the MPAA to achieve an 'R' rating, and Tim Lucas pays tribute to Michael Lennick, who died last year and to whom this booklet is thoughtfully dedicated. Also included are details of the transfers, credits for the films and a number of quality stills. Excellent.

| extra features – disc 2: David Cronenberg Early Films by Slarek |

|

This second disc contains four of Cronenberg's earliest works, the first two of which are, as far as I'm aware, making their home entertainment debut here. Indeed, what few reviews of From the Drain I've managed to track down describe it as being shot in black-and-white. It isn't, but the fuzzy workprint version you can find online is devoid of colour, and the commentators in question have assumed this is how the film was shot. Including remastered versions of Cronenberg's student shorts Transfer and From the Drain is a major coup for Arrow's release, and despite having been released previously on DVD, both Stereo and Crimes of the Future have been restored and remastered here (Stereo by Criterion, Crimes of the Future by Arrow) and look absolutely lovely. Transfer and From the Drain have been restored by the Toronto International Film Festival and do look good, but the source material is not quite as remaster-friendly as the later films.

At just over an hour in length apiece, Stereo and Crimes of the Future can be viewed either as Cronenberg's first two feature films or developments of the short film format he had already worked with in Transfer and From the Drain. Stylistically all four are examples of intellectual experimental cinema, meditations on the director's own theoretical musings on human communication, psychology, biology, behaviour and sexuality. If you're looking for early examples of Cronenberg's body horror then you're going to be out of luck. Indeed, if you come to any of these films expecting an entertainment, even in the unique manner that Cronenberg has fashioned over the years, you're likely to be disappointed. Despite some telling thematic touchstones, the films have more in common with the more arthouse work of William Burroughs, Anthony Balch, Chris Marker and Jean-Luc Godard than the twisted takes on exploitation cinema that were soon to mark Cronenberg's career.

And yet they are, in their way, distinctively Cronenberg pieces. This is especially true of the more fully developed Stereo and Crimes of the Future, particularly in the density of their behavioural and scientific theorising and their striking use of faceless institutional locations. Neither are narrative works in the traditional sense, having the detached sterility of educational films made by a government department interested only in evidence and hard facts. Emotional responses are discussed and to a degree observed, but never expressed. This is the sort of arthouse film-making that will instantly alienate a sizeable part of its potential audience, even those who count themselves as fans of the director's work, but just as many will take their anti-narrative and avant-garde elements dearly to heart.

Back in the 1980s, you could often find Stereo and Crimes of the Future films playing together in London independent cinemas, and at the very same time Cronenberg himself was suggesting in interview that they would prove pretty heavy going as a double bill. To a degree he's right, but given that both are cinema as art and intellectual discourse, they demand to be read differently to works whose prime purpose is to entertain. Whether you'll want to do so, or whether you'll be at all receptive to Cronenberg's very singular approach, is another matter entirely.

So, to the disc, which kicks off with...

Kim Newman on David Cronenberg's early works (16:51)

The venerable Kim Newman provides a really useful overview of Cronenberg's early short films, celebrates their black humour and suggest that in common with almost all of the horror directors of his generation, Cronenberg started out wanting to be Jean-Luc Godard. He highlights links between the director's short films and his later features, and states that Cronenberg means more to him as an artist than William Burroughs or J.G. Ballard, which is why he tends to watch eXistenZ more often than Crash or Naked Lunch.

Watching Transfer I was hit with a small wave of nostalgia, having attended film school back when 16mm was the recording format of choice and worked on a good many films where the young folk both in front of and behind the camera (of which I was one) were still finding their feet as artists and technicians. I remember one of my fellow students suggesting that only two types of film every got made in the formative first and second years, which he categorised as 'Where is My Reality?' soul searchers and 'Indians Over the Hill' attempts at micro-budget actioners. Entries into both categories were usually heavy going and had none of the slickness that modern HD cameras and digital editing software allow filmmaking hopefuls to practice with even before they land a place on their film course of choice.

Transfer is very much the sort of film that my fellow student would have instantly plonked in the 'Where is My Reality?' box, but unlike so many of its ilk, Transfer has a sense of humour. It also has a first project charm that's emphasised by performers who were probably recruited from the student body and camerawork (by the young Cronenberg) whose sometimes stuttering zooms are likely the result of his relative unfamiliarity with the equipment at hand. It's worth noting that Cronenberg was not studying film at the time but science, and was inspired to make Transfer after seeing a film titled Winter Kept Us Warm made by local boy David Secter.

The story has a psychiatrist who had fled to lands afar being tracked down by Ralph, his most persistent and demanding patient, who is anxious to continue his therapy. The set-up has a Python-esque comic surrealist flavour (made before the Python TV show began, it should be noted), with the doctor having made his new home in a furnished spot in a desolate, snow-covered field, while his fractured conversations with Ralph remain fluid through time and location jumps. The Godard influence is not hard to spot, but the performances here are bigger than you'll find in any of Jean-Luc's work. An offbeat experiment, it's actually rather fun, and it's hard not to warm to a psychiatrist who loudly complains that "an analyst has to dip his fingers into the murky, forbidding, scummy aquarium of the sick mind" and assures us that "Communication was the original sin."

The surrealism of Transfer continues in the more technically accomplished From the Drain, which begins with two men sitting motionless in a bathtub in a darkened bathroom as gentle acoustic guitar music plays in the background. The attempts of one of the men to communicate with his initially mute companion prompt only amused and despairing expressions or unclear gestures. The first man talks anyway and reveals that they are in a Disabled War Veterans' Recreation Centre, and claims that he comes here week after week in search of companionship and always seems get paired with an idiot. When his companion does finally speak his first word is "tendrils," and he suggests that the first man insert the bathplug to stop something making its way out of the drain.

Just who each of them are is teasingly uncertain and seems to change over time. Both may be war veterans, and either may be the Centre's Recreational Director, although just who is who becomes clearer (perhaps) as the narrative moves towards its conclusion. I initially tried to read something into the fact that the first man seems a little camp and the second is almost a cartoon geek, but soon came to the conclusion that both of these affectations were employed purely for comic effect. But there is definitely something going on under the surface here, with the location and the direction the story takes in its final minutes suggesting a political subtext that's worthy of further discussion, but only between those who have seen the film (sorry, no spoilers here). The concept of something organic emerging from a drain and potentially attacking the occupant of a bathtub also prefigures a memorable sequence in Shivers. It's an intriguing work – the performances are still dodgy but Cronenberg's camerawork is far more assured than it was on Transfer, and the opening credits (done on Dymo tape on a waste pipe) are neat.

At

the Canadian Academy for Erotic Enquiry, a number of volunteer

telepaths are observed and studied by the staff. The procedures

used and the conclusions reached are relayed in voice-over

by a number of the researchers, as the volunteers go about

their daily lives, interact with each other and participate

in the described experiments.

Although

a narrative is hinted at early on with the arrival of a

black-dressed character (Ronald Mlodzik, a close ringer

for a young Peter Cook) who could be either scientist or

participant, the on-screen action is largely observational

and often unrelated to surrounding scenes, at least in narrative

terms. The film itself is devoid of sound effects and music,

the silence broken intermittently by voices that explain

the work of the Academy and its findings in such coldly

analytical terms that it's sometimes too easy to hear the voice

but not the words. But it is here that the film is most

recognisably a Cronenberg piece, the dispassionate meditations

on the telepathic abilities of the subjects under investigation

proving consistently intriguing, particularly the concept

of telepathic addiction and the suggestion that telepathic ability is governed

in part by the level of attraction between telepath and

subject. This itself leads to some interesting postulations

on the politics of sexuality, the suggestion being that heterosexuality

and homosexuality are equally perverse and the only

true norm is bisexuality.

The

film is sometimes visually arresting, the large modernist

clinic with its long corridors and featureless walls acting

almost as an expressionistic extension of the emotionless

voice-over, and inevitably foreshadowing the use of similar

institutional constructs in Rabid and The

Brood. The most obvious signal of things to come,

however, is in the discussion of telepathy, some of which

would find its way into Scanners, specifically

the suggestion that drilling a hole in the forehead might alleviate

the pressure caused by the thoughts of others.

The

difficulty here is that much of the on-screen action is

a somewhat non-specific, casual interactions between characters

that are often divorced from the information being delivered

in voice-over. Although this itself is not an issue, at

63 minutes in length it can occasionally prove tough going,

as minutes tick by with little to keep the eyes busy and

nothing at all for the ears. As an experiment it is fascinating

and sometimes intellectually arresting, but for many the

length may prove self-defeating, as there is little variance

in the style and no development of story or, to any significant

degree, character. But it is intriguing, specifically for

its often complex and well devised theoretical musings,

its pointers to the director's later cinematic obsessions

and for its visual panache. That it was shot by Cronenberg

himself suggests that had he not chosen to direct, he could

have carved a successful career as a

cameraman.

Crimes of the Future (62:37) |

|

Despite

boasting more in the way of story and being shot in colour

rather than black-and-white, Crimes of the Future could in many ways be viewed as being the second part of

the cinematic experiment begun with Stereo. Visually there are immediate

and obvious similarities, notably in the concrete modernist

institutes in which both films are set and the black-dressed

lead character (again played by Ronald Mlodzik), and once

again this is essentially a silent film driven by voice-over.

This time around, however, it is spoken in the first person

and the soundtrack is peppered with semi-abstract sound

effects, recordings of water and sea creatures used by Cronenberg

to create the sense of, in his own words, "an underwater

ballet."

The

lead character, and the man whose musings guide us through

the film, is the splendidly named Adrian Tripod (the pronunciation

of which is difficult to accurately convey in print), a doctor at

a clinic known as The House of Skin, which since the death

of "the mad dermatologist" Anton Rouge has fallen

into serious decline. Only one patient remains, and control

of the clinic has effectively fallen to Tripod's two sullen

interns, whose actual role even appears to be Tripod unsure of. When the last patient

dies of a condition known as Rouge's Malady, Tripod transfers

to The Institute for Neo-Venereal Disease and develops a

technique for treating patients by telepathically connecting

with them through their feet.

I

mean, look at that plot. Pure Cronenberg. But as played out

here, driven as it is by an emotionless voice-over and with

no 'live' sound or dialogue, it's not quite as thrilling

as it sounds. The avant-garde minimalism of Stereo is also at the core of Crimes of the Future,

and despite the addition of some plot development, this is likely

to alienate almost as many hopeful viewers as its predecessor.

But it also shares all of that film's strengths, from its

intellectual scientific theorising to its cinematic fluidity,

and also has its share of pointers to the director's future

work, most memorably the patient who begins growing 'puzzling,

functionless organs', which touches on territory that was

to be more fully explored in The Brood and Dead Ringers. This blending of experimental

minimalism and twisted storytelling is ultimately seductive,

and towards the end involves us in a sequence as disturbing

as anything Cronenberg has done since, though interestingly

for what is suggested rather than what is actually shown.

Videodrome is a glorious mindfuck with logic and fierce intelligence at its base, and one of the finest achievements of one of the most imaginative and visionary directors in modern cinema. What I've failed to mention above is that this is the complete director's cut of the film, which unless you have the long discontinued laserdisc or the Criterion Blu-ray, you've probably never seen in the UK before.

Arrow's new Limited Edition Blu-ray and DVD set is a Cronenberg fan's wet dream, a gorgeously packaged, presented and featured set that every fan of this distinctive filmmaker's work should rush out and buy and put on display in a prominent place in their home the very moment it's released. We genuinely cannot recommend this package highly enough.

|