Note: there are major spoilers in the third-from-last paragraph that newcomers to the film would do well to skip over. A warning is given at the end of the previous paragraph and a bypass link has been provided.

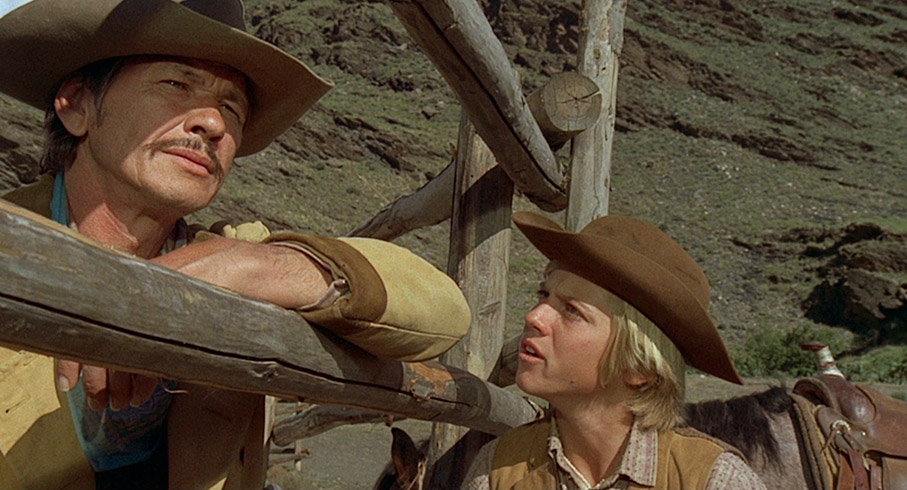

A lone figure on horseback rides across the plain in what we can assume from his attire is the American West of old, accompanied by the sort of folk-influenced song that was only found a home in westerns in the late 1960s and early 70s. As the figure approaches a wooden construct that we later learn was built by local Native Americans to house their dead, we discover that the figure is a boy (played by Vincent Van Patten) in his mid-teens, one whose facial expression is that of someone who is either lost or as yet has no set destination. He glances at a hand-drawn map that points the way to a place called the Nash Ranch, but it is hopelessly simplistic and lacking topographical detail. As night falls and distant thunder rumbles, the boy spots a cabin in the distance and rides towards it, and as he enters the yard a door is opened by a mixed-race man named Chino Valdez (Charles Bronson). The boy tells Chino that his name is Jamie Wagner and that he’s looking for work, and Chino gruffly invites him inside for a meal. When he first gets a good look at Chino’s face, young Jamie takes fright and makes excuses to leave, but is dissuaded from doing so by Chino’s assurance that he’s a long way from anywhere and is welcome to spend the night.

The following morning, Jamie rises late and when Chino returns from working his horses he finds him energetically sweeping the floor as payment for the previous night’s food and board. After pausing thoughtfully for a few seconds at the door, Chino suggests that Jamie rest his horse for a day and lends him one of his own, which Jamie quickly takes to. It then dawns on Chino that he needs to drive his latest herd of newly tamed horses into town today. “Can I help?” asks the now eager Jamie, to which Chino almost dismissively responds, “Don’t need it,” but he does allow Jamie ride along anyway. “Just stay out of the way,” he curtly advises.

After reaching the town and selling the horses, Chino pauses to observe the arrival of a stagecoach, from which wealthy local rancher Maral (Marcel Bozzuffi) and his attractive sister Catherine (Jill Ireland) alight. When a goon named Ricardo (Antonio Tarruella) taunts Chino and his part-Indian heritage by saying, “I can read your dirty mind, Indio,” Chino violently smacks him up and throws him into the street. The goon draws a gun but is coolly persuaded to stand down by Maral, who only has to say the man’s name twice to force his compliance. Chino then gives Jamie some money to stable their mounts and buy himself a decent meal, then ambles into a nearby bar for a few drinks. The owner (Luis Prendes) is dismayed at his arrival, having just repaired the bar following a previous fracas, and when Ricardo and his chums walk in looking for a fight, the bartender’s fears prove to be fully justified.

Okay, I probably need to pause here to contextualise the reaction I found myself having to the 1973 The Valdez Horses even at this relatively early stage. I fell in love with 70s American cinema back when cinemas were where you went to watch these movies, a period of my youth when I had no other worldly distractions and I was seeing a good couple of hundred films a year on the big screen. By then I had latched on to specific directors, but the only American actor whose career I actively followed at the time was Clint Eastwood. Like I said, I was young, but in my defence I should note that even at this point in his career, Eastwood was also proving himself as a director of note. One actor whose work I perhaps paid too little attention to was Charles Bronson. I saw only a small number of the films in which he starred and I'll confess that I was not particularly taken with them or with Bronson as a performer. As a result, there are several now well-regarded movies from that era that I’ve only started catching up with in recent years. Attitudes and tastes change, of course, but the first of the Bronson films from this era that I later sought out did little to alter the prejudicial view I’d formed back in my teens. The notable exception was Walter Hill’s blistering debut feature, Hard Times, the first film to prompt a serious rethink about Bronson on my part. He was perfect casting here, his weather-beaten looks, muscular frame and taciturn way with dialogue really working for a character I now have trouble imagining anyone else playing. Since then, I was introduced to his too-rarely seen lighter side in the 1975 Breakout, and earlier this week found myself nodding in appreciation at his performance as Mafia foot soldier Joe Valachi in The Valachi Papers, which is being released alongside this very disc by Indicator.

I’ll thus admit to coming to The Valdez Horses, which I’d never seen and knew only a little about, half-expecting a run-of-the-mill 70s western in which Bronson played Bronson, with stonily delivered and cut-down dialogue interrupted by occasional explosions of violence. Which, in a way, is exactly what we get, but if ever there was a movie designed to smack my silly preconceptions smartly in the mouth, then The Valdez Horses is it. Even before Chino and Jamie head towards town to sell the horses, there’s a seductive low-key quality to the filmmaking and particularly Bronson’s performance that really caught me by surprise, and it’s worth noting here that the film was directed by John Sturges, the man who helmed The Magnificent Seven and The Great Escape. Or was it? I’ll be coming back to that question at the end of this review. When the action does briefly kick off it does so sharply, with Ricardo quickly floored by three swift and painful-looking hits, and when Chino throws him into the street he doesn’t pause to take aim, with the result that the sizeable Ricardo collides with the diminutive Jamie and knocks him to the floor. So violent is the collision that I can’t help wondering if this was an on-set accident. When Ricardo and his buddies show up to pick a fight with Chino in the bar a short while later, the choreography (by Bronson, apparently) and swift, no-nonsense brutality of the bust-up that follows is a text-book example of how to stage such a fight for film. Yet what intrigues most about this scene are the questions it raises and elects not to answer, suggestions of a backstory involving Chino and his past interactions with the townsfolk that we’re left to ponder and expand on ourselves. Similarly, when Maral steps off the stagecoach it initially seems like Chino is seeing him for the first time, but the way he marches into Maral’s house later to confront him about his barbed wire fences makes it clear that the two have enough of a history for Chino to know his way around Maral’s property. It’s the sort of film storytelling, where information is imparted through suggestion and the actions and attitudes of the characters rather than through spoken exposition, that I really appreciate and instantly warm to.

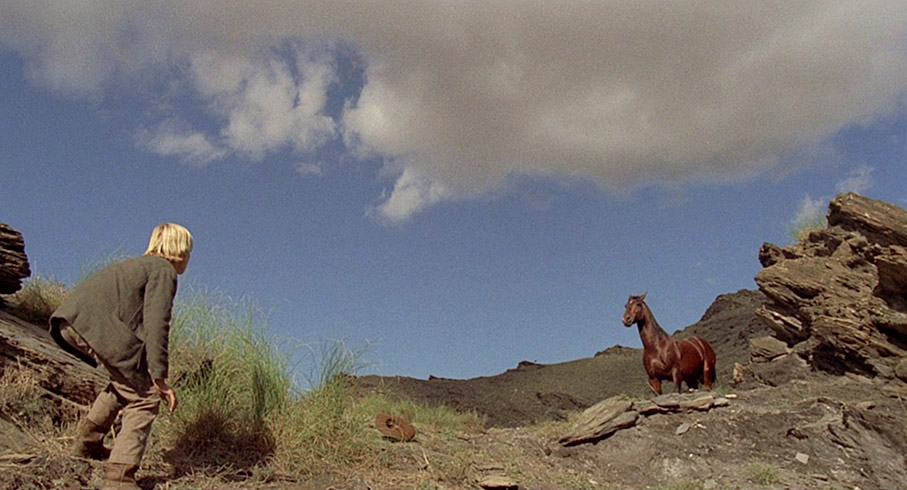

That Chino and Jamie will bond over time seems likely even before that first ride into town, and the relationship that develops can’t help but have just a whiff of Shane about it, albeit with the neat twist that here it’s the boy who is the stranger with a mysterious past who rolls up at a homestead looking for work. As it is with Chino, Jamie’s backstory is left teasingly explained. When he first arrives at Chino’s shack he awkwardly claims not to have run away from home, but we never discover if this is true, and if it is then the fate of his parents is a matter for interesting conjecture (answers are provided in Lee Hoffman’s source novel, but in the context of the film I’m happier without them). Jamie certainly responds to Chino as a surrogate father figure, jumping at the chance to stay one more night and the later offer of paid work when the two begin to form a real connection, the gradual evolution of which is subtly illustrated by how long it takes Chino to start calling Jamie by his name. Every bit as intriguing is Chino’s relationship with the horses he catches, tames and trades. This is particularly true of Flag, a thoroughbred he has raised from a young colt and with whom he appears to have an almost spiritual connection. It’s something Jamie gets a taste of when observing the herd that this special horse effectively commands and Flag appears out of nowhere and stands tall above him, adopting a position of authority and strength whilst taking time to study this young newcomer.

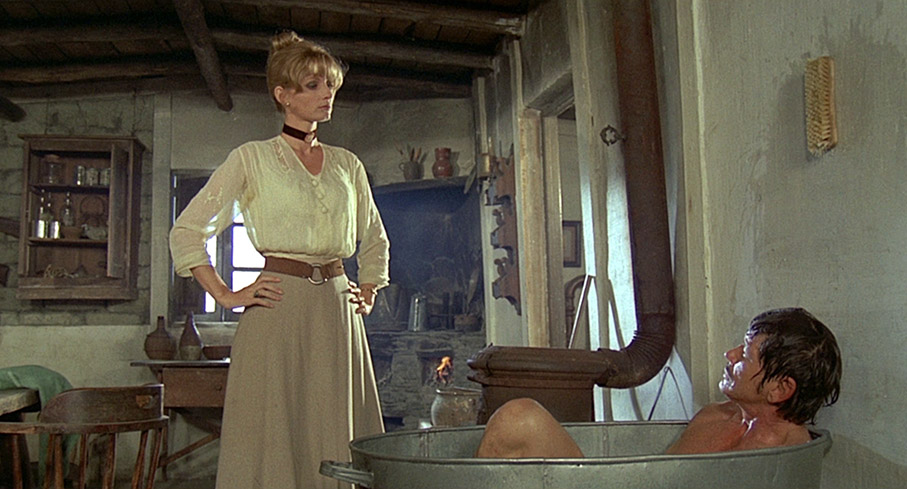

Even before the halfway mark it seems clear that the film is less concerned with advancing a plot it has barely laid out by this point and more focussed on the developing friendship between Chino and Jamie and Jamie’s gradual evolution from teenage boy to young man. Possible disruption arrives early when Chino strides into Maral’s house and makes first verbal contact with Catherine, who starts visiting Chino on the pretext of buying a horse and ends up romantically involved with him. Their hesitant courtship peaks with an odd and ultimately discomforting seduction scene, as Catherine watches two horses mating and Chino effectively forces himself on her in a manner that few would have trouble qualifying as attempted rape, something she vigorously resists and then willingly gives in to. When Maral forbids Chino to ever see his sister again, their future union in defiance of him might seem inevitable, but things do not play out quite as expected. Indeed, another thing that really caught me out about The Valdez Horses is how it plays with and ultimately kicks against convention and expectations, and I’m about to drop a few serious spoilers here, including how the film ends, so newcomers to it would do well to hop past the following paragraph to avoid them (click here to do so automatically).

Although primarily character-focused, The Valdez Horses does conform to the second of writer Frank Gruber’s eight western plot-lines that define the genre,* one in which rustlers or more commonly large landowners attempt to force out the rightful owners of small farms or ranches. Traditionally, this builds to a David and Goliath battle in which the smallholders, sometimes assisted by a skilled outsider, manage to defeat the wealthy rancher and are able to keep the home they were earlier convinced they would lose. Here, all the components are in place for that to occur, with Chino informed that Maral now owns the land on which his homestead sits, then cruelly baited and later whipped by Maral and his men, which he responds to by grabbing a rifle and heading out to take revenge on the men who have so cruelly wronged him. Yet he ultimately settles for dispatching just a handful of his foes before electing to pack up and head off to who knows where, burning down the home for which he once had future plans, unexpectedly parting company with Jamie and abandoning all hope of ever seeing Catherine again, and leaving Maral to continue his doubtless nefarious business and further expand his empire. It’s a startling and frankly bold ending that favours realism over wish-fulfilment, an acknowledgment of the life-changing influence that those in positions of wealth and position have over us ordinary mortals and their willingness to destroy lives in pursuit of profit and power. Other elements may have dated, but this aspect is probably more pertinent than ever in today’s corporation-dominated world.

Also pleasingly reflective of then changing times, albeit with one small caveat, is the film’s warmly sympathetic portrayal of Native Americans, represented here by the small and slowly dwindling tribe with which the half-Indian Chino has a strong bond. That they are played by Spanish, Italian and in one case Paraguayan actors may date the film, but the portrayals feel and look surprisingly authentic, and a scene in which Jamie attempts a trade with a young Native American girl, despite the lack of common spoken language, is touchingly and believably handled. You might call into question whether the rather significant life lesson she later teaches Jamie would be something that would be allowed to happen within this tight community, but when Chino is seriously injured and Jamie takes him straight to the tribe for help, it feels like a logical move that says much about what Jamie has learned from his brief time with them and what he has observed about their respect and fondness for Chino.

The Valdez Horses really took me by surprise, and I mean that in a positive way. I’m not sure exactly what I was expecting – particularly considering it technically qualifies as a spaghetti western – but it certainly wasn’t a film as gentle, as character-centric and as effective in its use of subtle suggestion over loud statement as it proved to be. In the character of Chino, I’d argue that Bronson found the perfect showcase for his too-little seen skills as a low-key and naturalistic performer and preference for minimal dialogue. He really is excellent here, but is matched all the way by Vincent Van Patten’s convincing, likable and well-judged portrayal of Jamie. The two have a real chemistry that I completely bought into, and as a result I soon found myself rooting for their father-son bond and for a future together that I then began to fear for as the second-half problems mounted for Chino. I really enjoyed this film, for its favouring of character over plot, its bucking of conventions it appears initially to be following, its moments of unexpected poetry, its winning lead performances, and for the direction of John Sturges and… well, I guess it’s time we had a talk about that.

| who directed what in The Valdez Horses? |

|

Even before watching this film for the first time I was aware that there had been some past uncertainty about just who directed what. I've seen claims that John Sturges was replaced early in the shoot by Italian director Duilio Coletti and directed little or none of the film, while in his interview on this disc, make-up artist Giannetto De Rossi states categorically that he only worked for Sturges and never saw Coletti. On UK and US prints of the film, Sturges is credited as the sole director, whereas Italian prints have it down as a John Sturges film but credit the direction to Duilio Coletti.

Perhaps the most plausible and detailed take on all of this comes from writer Paul Talbot, who in the below-detailed commentary track claims that the film’s investors were unhappy with the cut that Sturges delivered and demanded reshoots, which Coletti was brought in to handle because Sturges was already involved in the prep for his next film. It seems likely that some members of the original crew were not available for these reshoots (cinematographer Armando Nannuzzi, for example, was replaced by Godofredo Pacheco), and it’s thus quite possible that De Rossi was also not re-hired, which would explain why he never worked for Coletti. There may well be more on this in the accompanying booklet, but having not seen it yet I'm having to speculate.

I can’t testify to the source of Talbot’s phenomenally detailed information on the shoot, but he speaks with some authority about the changes made to the opening title credits on the Italian prints (this was apparently all about securing extra funding), and is also able to identify which sequences were shot by which of the two directors. Assuming he’s correct – and I have no reason to question him on this – I would have to take issue with the suggestion that Coletti’s work was somehow inferior to Sturges’. As evidence I offer up the early barroom fight, which Talbot notes is shot handheld, a technique Sturges did not use. Yet the sequence is a belter, choreographed and staged with the skill and timing of a grade-A martial arts movie, and the handheld camera subtly adds to the dynamism of the scene. I’d go as far as to say that had I not been informed that two directors were responsible for different sequences, I wouldn’t have guessed it.

I’m assuming from the opening logo that this 1080p transfer, which is framed in its original 1.85:1 aspect ratio, was supplied to Indicator by StudioCanal, and while strong for the most part it is just a couple of notches shy of top-notch. I certainly wouldn’t judge the overall quality by the opening credits, which do display some visible imperfections. There’s a visible jump in quality once they conclude and the result is generally pleasing, with well-balanced contrast, a warm and sometimes earthy colour palette and a generally strong level of detail that does soften a little on some wider shots and is never quite as crisp as some of Indicator’s best transfers. That said, it's still a very solid job and the best material is very attractively rendered, with blue skies vividly captured and a golden glow to firelit scenes. Title sequence aside, the transfer is clean and free of damage and a fine film grain is visible.

The DTS-HD Master Audio 1.0 mono soundtrack does show its age in the audible range restrictions on the dialogue, but clarity is never an issue, the sound effects and music are both fine and there’s no trace of damage or serious wear.

Optional English subtitles for the deaf and hearing impaired are available.

There is also the option to play the film under its Italian title of Valdez il mezzosangue, which opens with the Italian title sequence, which can also be viewed separately in the special features. The dialogue remains in English, however.

Audio Commentary with Paul Talbot

In the first of three special features that mirror those on Indicator’s simultaneously released Blu-ray of The Valachi Papers, author Paul Talbot, whose books include Bronson’s Loose! – The Making of the Death Wish Films and Bronson’s Loose Again! – On the Set With Charles Bronson, provides another detailed flood of background information on the film, its making and its release. He usefully makes comparisons to Lee Hoffman’s source novel, highlighting aspects of the book (which he quotes from) that were not used and sequences that were created specifically for the film, as well as pointing out which ones were directed by John Sturges and which by Duilio Coletti – by his estimation, 74 minutes of the film was directed by Sturges and 23 minutes Coletti. We get information on many of the actors and crew members, Bronson’s daily fitness routine, the horses, the soundtrack and theme song, the release, the critical response and much more. Another very fine, very informative commentary from Talbot.

Giannetto De Rossi: Dust and Sweat (15:38)

What is clearly the second half of an interview conducted with the film’s Italian make-up artist, Giannetto De Rossi (the first half is on Indicator’s Blu-ray of The Valachi Papers), is unsurprisingly focused on The Valdez Horses. The admiration he expressed for Bronson in the previous interview is taken to new heights here with his claim that the actor was like a Greek statue and so perfect in his imperfections that the less make-up you put on him, the better he looked. He recalls being excited at the prospect of working with director John Sturges, but ultimately felt that his ideas were “few and confused” and that he didn’t bring anything to the film itself. He does, however, state that he never saw another director do any work on the film, but I have expressed my own theory about that above. He talks a little about staging and providing make-up for the whipping scenes, reveals that the way to spook horses is to hold their testicles (must remember that), and looks back at his relationship with his wife Mirella, who worked uncredited on the film as its hairdresser and who it would appear had recently passed away when this was shot. Touchingly, this interview is dedicated to her memory.

Stephen Geller: Gambling on the Horses (20:09)

Uncredited first screenwriter on the film, Stephen Gellar, reveals how he came to adapt “a wonderful little novel” into what he immodestly describes as “a knockout first draft” of the script for Dino De Laurentiis. He then gets into some of the problems that followed, most of which appear to centre around a falling-out he had with director John Sturges, about whom he has nothing positive to say. As he was in his interview on Indicator’s Blu-ray of The Valachi Papers (which, again, was clearly filmed at the same time), Geller is an energetic, engaging and uncompromising raconteur, but his damning claim that Sturges regarded the project as “a piece of shit” doesn’t really tally with the thoughtful and captivating work that was ultimately delivered.

Alternative Titles and Credits

There are two alternative opening credits sequences here, the Italian release version titled Valdez il mezzosangue (3:39) and the initial American release version, simply titled Chino (3:57). For the record, The Valdez Horses is far and away the best and most appropriate title, one taken directly from Lee Hoffman's source novel. The American version is framed open matte 4:3 and appears to have been sourced from a low-band tape recording, but apart from the title change is identical to the one featured on this disc. On Valdez il mezzosangue (3:49), which I gather translates to Valdez the Halfbreed, Vincent van Patten is no longer listed as a lead player and his name has been relocated amongst the supporting cast, while Marcel Bozzuffi and Jill Ireland’s names have been swapped around so that Bozzuffi’s appears first. The screenplay is credited here to Dino Maiuri, Massimo De Rita and Clair Huffaker (only Huffaker is credited on the US and UK release prints), and while it is identified as a John Sturges film, the only credited director is Duilio Coletti.

French Theatrical Trailer (3:06)

An odd, almost dialogue-free trailer with no narration or explanatory captions, one that strings a collection of mainly action-driven shots together to the title song, including a few from the climactic scenes and a couple of shots not included in the film itself.

TV Spot (0:28)

An uninspiring sell for the film under its American release title of Chino.

Image Gallery

35 screens of crisp monochrome promotional photos, coloured-in German lobby cards and an impressive array of international posters.

Also included is a Limited Edition exclusive Booklet with a new essay by Roberto Curti, an archival on-set report with contributions from Charles Branson, Jill Ireland, and John Sturges, interview extracts from Bronson and Ireland, an overview of contemporary critical responses, and film credits, but this was not available for review.

The Valdez Horses is an underrated film that both surprised and captivated me, and is a real showcase for how good Bronson could be when given the right role and the right director(s). It had me riveted from its opening scenes and as an aside it also provides a useful tip on how to scrub your back when you have no-one to do it for you – you’ll need to see the film to make sense of that one. A solid transfer and a fine set of extras make this an easy recommendation.

- The Union Pacific Story. The plot concerns construction of a railroad, a telegraph line, or some other type of modern technology or transportation. Wagon train stories probably fall into this category.

- The Ranch Story. The plot concerns threats to the ranch from rustlers or large landowners attempting to force out the proper owners.

- The Empire Story. The plot might involve building up a ranch empire or an oil empire from scratch, a classic rags-to-riches plot.

- The Revenge Story. The plot often involves an elaborate chase and pursuit, but it may also include elements of the classic mystery story.

- The Cavalry and Indian Story. The plot revolves around taming the wilderness for white settlers.

- The Outlaw Story. The outlaw gangs dominate the action.

- The Marshal Story. The lawman and his challenges drive the plot.

An eighth was later added titled Going Native to include stories like Thomas Berger's Little Big Man, in which a white man or woman makes their home with a native American tribe. |