|

Please note: There are some spoilers for newcomers to the film,

so proceed with caution if you've not yet seen it.

| |

"The forefinger slipped through the trigger guard and the gun spun, coming up into the firing position in the one unbroken motion. With him that old pistol seemed alive, not an inanimate and rusting metal object, but an extension of the man himself." |

| |

Shane – Jack Schaeffer |

There's a shot at the start of George Stevens' magisterial 1953 western Shane that is simultaneously both sublime and sublimely imperfect. As the titular Shane (a chance-cast Alan Ladd) rides towards the homestead owned by Joe Starrett and his family, young Joey (Brandon De Wilde) is hidden in the brush stalking a drinking deer. As Joey takes aim with what we soon discover is an unloaded rifle, the deer raises its head and looks off towards the still distant figure of an approaching rider, and the camera is positioned so that he will be framed by the antlers of the deer. Whether this was a chance thing or down to director Stevens' famously meticulous planning I couldn't say, but it's a hell of a way to introduce your title character. Except just before the moment Shane would have been positioned centrally between the deer's antlers, Stevens cuts away to the watching Joey, and when he returns the moment has passed. I have no doubt that there are editors and cineastes the world over who let out a yelp of disbelief at Stevens' decision not to let the shot run just two seconds longer to allow the rider to reach that optimum point of visual symmetry. But there'll be just as many others who recognise that the decision to cut away at this point may well have been forced by the deer lowering its head again. It's also quite possible that Stevens and his editors, William Hornbeck and Tom McAdoo, knew exactly how long that shot should run for the rhythm of scene to work, and that striking though the resulting image might have been, it would have contributed nothing to the story or character. And the editing and framing decisions made elsewhere in the film are so precise that I think we can be confident that whatever the reason for the timing of that edit, the decision was deliberate and carefully thought through.

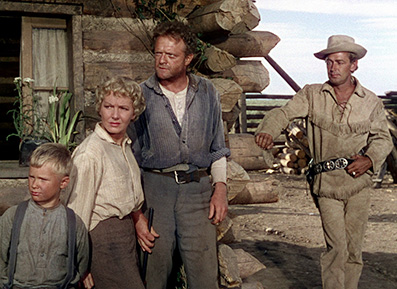

As if to bring this home, just seconds later we see Shane in mid-shot for the first time in what has to be one of the most iconic character shots in western film history (see below), appropriate given that Shane remains one of its most iconic figures. His greeting is friendly and his intentions innocent, seeking as he is a route through land that was once devoid of fences. Joey is bashful in the presence of this stranger, while his father Joe (an impressive Van Heflin) is cautiously welcome, and Joe's wife Marian (Jean Arthur) is, well, what exactly? When she first lays eyes on this visitor there's more than simple curiosity visible in her expression.

There's a lot established in these opening minutes. When Joey innocently cocks his rifle and Shane whips around, his eyes alert and his hand hovering purposefully over his holster, we are clued into something important about his past. And when a party of men ride up to the house and Joe curtly assumes Shane is working with them and demands that he leave, we quickly learn that Joe and his fellow homesteaders are being pressured by ruthless cattle baron Rufus Ryker to abandon their properties and hand their land over to him. Shane agrees to leave, but when the men ride up he saunters back and informs them that he is Joe's friend, which appears to be enough to encourage them to depart. Realising that he has misjudged this stranger, Joe invites him to stay for dinner and offers him somewhere to bed for the night.

What follows is one of most perfectly realised male bonding sequences in cinema history, as Shane wordlessly elects to repay the family's kindness by picking up an axe and attacking the tree stump that Joe was working on when Shane arrived at the house and has been fighting to uproot for the past two years. The manner in which the sequence is shot, cut and scored (by Victor Young) elevates this new friendship to the level of blood brothers in just a few short but exquisite minutes of screen time, their final moment of triumph thrillingly captured as the camera appears to be drawn towards them by their physical effort. I've watched this sequence more times than I care to count and it still makes the hairs on my arm stand on end every single time.

In a film populated with what at first glance appear to be genre archetypes, Shane is and remains an enigma, a man whose backstory we can only guess, one who when we first meet him is riding away from his past and towards a future whose shape and location even he is unsure of. His early instinctive reaction to potential danger tells us that he was likely once a gunfighter, while a later demonstration of his shooting skills for the awe-struck Joey suggests he was a force to be seriously reckoned with. Yet everything about his words, his actions and his demeanour paints him as a man who is defined by decency, fairness and a sense of honour. Where most movie gunfighters would go nowhere without their six-shooters, from the moment he takes off his gun belt to sit down for dinner with his new hosts, Shane is content to leave his at the Starrett homestead. Early on he repeatedly steers clear of conflict, complying when Joe mistakes him for one of Ryker's men and orders him to leave, and when humiliated in a bar by cocky Ryker cowhand Calloway (played by future genre heavyweight Ben Johnson), instead of delivering the expected pounding he walks away to the mocking hoots of his amused tormentors. Why, one wonders, would a man like Shane do this? Is he a reformed gunfighter determined to put his dark past behind him? Has one too many deaths left him broken and no longer able to deal with conflict? Or is he all too aware of the likely consequences for Calloway should he respond in the manner to which he has become accustomed?

Whatever it is that Shane is searching for, there are strong signs that he may have found it in the Starrett home and particularly in the almost brotherly bond he forms with young Joey. From the moment he arrives, Shane becomes an object of idolisation for the boy, and it's Joey's refusal to accept that Shane could walk away from a fight because he was scared that proves the driving force behind Shane's return to the bar to confront and engage Calloway in a fist fight that tests the metal of both men. It's a brawl that the bruised and battered Shane ultimately wins, but only by a whisker. Here more than ever there's a sense that without his guns he's not so different from Joe in strength or resolve, something brought home when he's set upon by Ryker's men and saved from a serious beating by Joe's intervention. As the two take on the gang, at one point standing back-to-back and pausing briefly to turn and flash each other comradely smiles, the bonding that began with the tree stump uprooting is taken to what at this point feels like a logical conclusion.

Its after this that things take a darker turn, as the even more determined Ryker (who, in an unusual twist for such a character, is keen to avoid trouble with the law even though it is three days' ride away) sends for a gunslinger named Wilson, played to perfection by a studiously malevolent Jack Palance. Even this potential genre staple does not play to expectations. When the easily goaded and slightly drunk Stonewall Torrey (the always lovely Elisha Cook Jnr.) comes into the bar and starts sounding off, instead of picking a fight Wilson swivels on his chair, eyes Torrey up like an entomologist studying a curious new breed of insect, then turns back to his table and quietly converses with his employer. "Is that one of them?" he mutters under his breath, to which Ryker responds ominously, "You'd get him to draw without any trouble." Yet even as Torrey's defiant words are aimed directly at Ryker, neither he nor Wilson rise to the bait. Wilson's not just a gun for hire, but one armed with patience and the willingness to carefully plan ahead.

The confrontation between Wilson and Torrey that eventually comes has long since passed into movie legend, and rightly so. Everything about the scene is either carefully thought through or blessed by chance, as when a perfectly timed cloud passes over the sun and darkens the scene in a manner that feels like an expressionist statement of mood and intent. So inevitable is it that Torrey will be challenged and lose to Wilson that the tension derives not from if he will be killed but exactly when it will happen and how humiliating it will be. The inequality between the two men is established from the moment they exchange their first words, as Wilson stands tall on the porch of the saloon in his finest black duds, while the scruffily dressed Torrey struggles to keep his feet as he unsteadily negotiates the cart-furrowed mud below. Taunted by Wilson about his allegiance to the Confederacy, Torrey draws first, but even before his gun is halfway out of its holster, Wilson's is pointing directly at his chest. What hurts the most is the pause that follows, a couple of short seconds during which you're given time to cling to the hope that Torrey will escape with his life, having learned a lesson from the speed of Wilson's draw about just what he and the other homesteaders are up against. When Wilson fires regardless in a calculated and sadistic demonstration of his power, the shock is considerable, despite the seeming inevitability of this result.

In this respect and others, there's an argument to be made for citing Shane as the first modern western. Almost forty years before Unforgiven, Shane was questioning the gunfighter's heroic status and suggesting not only that his days are numbered, but that his passing might be a positive thing. And when guns are fired in Shane, the destructive power of the weapon registers like never before, with pistol shots exploding like cannon fire and their impact throwing their victims from their feet. As a veteran of World War 2 who took part in the liberation of the Dachau extermination camp, George Stevens had contempt for films in which six-shooters were used "like guitars" and was determined to show what actually happened when a man was hit with a .45 calibre shell. To this end he created a specific sound effect by firing a small cannon into a waste bins and had his actors wired so that they could pulled backwards off their feet by technicians when they took a bullet hit (it's a little ironic that a technique devised to bring realism to a previously stylised action is now widely used in action cinema to exaggerate the effects of impacts to the level of absurdity). Stevens also insisted that costumes and fittings be selected for their authenticity and appropriately worn down, something we tend to associate more with later and more revisionist genre works. This kick against convention extends to texturing characters that by this point had almost become genre stereotypes, with even the seemingly ruthless Ryker allowed a defiant speech to Joe in which he eloquently makes the case for the work he and his fellow pioneers put into taming the land that these relative newcomers to the region are now able to farm.*

There's also a modernity to Stevens' camera placement and editing decisions (the film famously spend considerable time in post-production), with entire sequences covered in a single wide shot with none of the expected cuts to mid-shot or close-ups for emphasis. When the action hots up, however, Stevens' coverage and editing rival that of modern action cinema – he even foreshadows a trend that crept into martial arts movies a few years back of observing a fight from behind fittings or furniture, as if from the viewpoint of a nervous observer. Other shots seem to deliberately invite us to find deeper meaning, as when Marion and Joe confront Shane about the inevitable showdown with Wilson and in one shot Shane is shielded from view and symbolically isolated from them by an open door, or the striking image of a rain-drenched by physically static Shane framed by an open window like a gallery portrait, one that Marian then converses with in a moment that visually borders on the surreal. Close-ups are sparingly but always memorably used, few more so than the low angle shot of a ferociously determined Joe as he wades into the bar fight brandishing a pickaxe handle.

The casting is absolutely spot-on throughout but so nearly resulted in a very different film. Stevens had wanted Montgomery Clift as Shane and William Holden as Starrett, but when both chose to work on other projects instead he was presented with a list of available actors and picked Alan Ladd, Van Heflin and Jean Arthur in a heartbeat. I'd argue that Ladd in particular is sublimely cast here, absolutely nailing his portrayal of an decent man with a troubled past that he is trying to put behind him but cannot quite escape. There's a low-key subtlety to Ladd's performance that adds to the sense that this is a more recent film than its release date assures us, allowing Stevens to drop small hints about the man that Shane once was and his yearning for a life that knows he will never have. This really hits home in two tellingly self-reflective facial expressions, the first when the family are preparing to head into town Joe talks about having a woman that's worth waiting for, the second immediately after Shane demonstrates his shooting skills for Joey – just what is he recalling here that so haunts him here?

That Shane will have to take on Wilson in a climatic test of the skills from his mysterious past is inevitable from the moment Wilson rides slowly into town (part of Wilson's menace is that he does nothing at speed except draw his pistol). By the time Shane finally picks up his guns again, he's been softened and even domesticated to the point where his victory against Wilson no longer feels guaranteed, and even before he can face him he has to battle with Joe for the right to take on a man that only one of them is even remotely equipped to defeat. It's a violent brawl that recalls an earlier conversation between Joe and his son when Joey asked his father if he would be able to beat Shane if the two came to blows. More than once Shane comes close to losing a fight, and it's clear that despite what is inferred about his past, in the end he's just a man, one quick on the draw but as vulnerable and fallible as any of the homesteaders he so selflessly aids.

In a genre that was fond of descriptive titles – think The Searchers, The Wild Bunch, The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance and any number of others – Shane is a seductively uninformative one that gives no hint of the plot or even the genre in which it very comfortably resides. Yet it is so appropriate, as while an argument could be made that the fate of the Starrett family is more central to the story, it's the impact that Shane has upon their lives and the land on which they have chosen to live that drives the narrative forward and gives it its meaning. It seems likely, however, that the choice of title was governed largely by the fact that the book on which A. B. Guthrie Jr. and and Jack Sher's screenplay was based – the first novel by genre writer Jack Schaeffer and originally published in Argosy Magazine under the more descriptive but equally intriguing title of Rider From Nowhere – had been successful enough to avoid any serious confusion about the genre in which it sits.

The book is, as it happens, a damned fine read, but one I'd personally save until after the film, as while structurally similar, it differs enough in detail to prove potentially distracting if read just before you watch the film for the first time. And while I don't believe a movie should be required to be completely faithful to its source novel (they are, after all, very different media), one difference between Shane and its source that has always struck me is the film's slightly softer presentation of Marian, who while captivatingly played by Jean Arthur in her final film role (at 50 years of age and looking considerably younger), she has a no-nonsense strength of character in the novel that is only fleetingly glimpsed here. This is particularly evident in her late film plea to Joe for them to pack up and leave, an idea that he steadfastly refuses to entertain. But at the end of the novel it is Joe who talks of pulling up stakes and moving to Montana, and the resolute Marian who talks him out of it. It is also she who best encapsulates the impact that Shane has had on their lives when her downcast husband mourns the fact that Shane has departed. "He's not gone," she says. "He's here, in this place, in this place he gave us. He's all around us and in us and he always will be." Part of the greatness of this thrilling, beautifully made and intermittently breathtaking film is that by the closing frames we know this in our hearts without ever having to be told the words.

This double-disc Blu-ray release from Eureka is unusual in its inclusion of three versions of the very same cut of the film in two different aspect ratios. The maths don't seem to add up there, so clearly some clarification is needed. Shane was shot in the Academy ratio of 1.37:1 and spent a considerable amount of time in post-production. On its completion it was selected by Paramount to be their first foray into widescreen, apparently chosen because it was believed the film's extensive use of medium and wide shots would not suffer too severely from the resulting crop to 1.66:1. Eureka has thus included both the 1.37:1 original framing and the cropped 1.66:1 version that was shown in cinemas. While the reframing does not seriously impact the film as a whole (there are big skies here and cinematographer Loyal Griggs is often generous with the headroom), there are a fair few moments when the impact on the composition is clearly evident, clipping the peaks of the mountains that so majestically dominate the landscape mountaintops and occasionally cutting people in half at the bottom of frame.

The original 1.37:1 framing (top) compared to the 1.66:1 theatrical version (middle)

and the 1.66:1 optimised version (bottom). |

|

|

|

|

|

|

So what of the third transfer? This is also framed 1.66:1, but here the framing has been 'optimised' for this ratio, a process overseen by George Stevens Jnr., the director's son. While on the theatrical release the crop was applied evenly to the top and bottom of the picture via a plate fitted to the projectors when screened in cinemas, the image here appears to have been adjusted on a shot-by-shot basis to minimise the harm to the original composition and correct some of the more uncomfortable detail clipping at the top and bottom of frame. You can see the difference in the frame grabs above. While the inclusion of both the 1.66:1 versions is a completist's dream (it's worth noting that they are only included in the 2-disc limited edition release), for me the 1.37:1 edition is the only way to go. This was the ratio in which the film was shot (Stevens himself apparently objected to the cropping), and while I'll accept it was not screened that way, of the three versions it's the one that feels most 'right'. I'm guessing that Eureka feel this way too, hence the decision to give the 1.37:1 version a disc of its own and a file size of 34GB at an optimum bitrate, while the two 1.66:1 versions share a single disc and occupy approximately 22GB apiece. They still look great, but the 1.37:1 transfer absolutely shines. Talking of which...

Shane was shot on three-strip Technicolor and I'll wager has not looked as gorgeous as it does on this Blu-ray since it was first screened for audiences in cinemas back in 1953. I'm getting used to seeing older films looking great on Blu-ray when they carry the Masters of Cinema label (and even if they don't, as it happens), but I was still knocked out by what they've delivered here, perhaps because I know the film primarily from TV screenings and an older DVD release, both of which this transfer blows out of the water. There's a warm earthiness to the colour scheme, though much of this is down to the realism of the production design and costumes, with unpainted wood figuring strongly on buildings, walls and fittings and the clothing chosen for its practicality rather than its aesthetic appeal. The brighter colours are there (a couple of the shirts at the town's Independence Day dance really pop) and the blue skies are always handsomely rendered. The contrast is perfectly judged, nailing the black levels without sucking in detail and never burning out highlights, and the sharpness and level of picture detail fully justify this title's Blu-ray only release. Lovely.

One aspect of the film that has suffered on some previous transfers is its use of day-for-night for the night-time exteriors (if you're not familiar with the term, check out the footnote of my review of Dracula Prince of Darkness, where I've explained it in some detail), which were often brightened in the transfer to video for broadcast, effectively stripping off the post-production darkening of the picture that was supposed to make scenes that were shot in daylight look as if they were taking place at night. If you want an example of how this completely changes the tone of the scene, re-watch the ending of the film and then take a look at the included theatrical trailer and you'll see a scene that takes place at night suddenly bathed in the light of the noonday sun. Here the day-for-night grading has been restored, and then some – a couple of the scenes are dark enough now (when the Starretts and Shane return home to find Ryker waiting to propose a deal is a prime example) to make me glad I watched the film at night with the room lights low. But if your viewing conditions are ideal and your screen correctly balanced it looks absolutely right, and the essential picture detail is still clearly visible.

There are two soundtrack options here, Linear PCM 1.0 mono and Linear PCM 2.0 stereo, which I have to presume was remixed for Paramount's restoration. Both are in good shape considering the film's age, with the expectedly range restrictions but no trace of damage or distortion on either. There's little if anything in the way of effects or dialogue separation on the stereo track, but it is slightly louder and brighter than the mono original.

Optional English subtitles for the deaf and hard of hearing are also available for the main feature.

Commentary

This commentary by the director's son George Stevens Jnr. and regular collaborator Ivan Moffat (who worked with Stevens during the war, was associate producer on Shane and one of the screenwriters on Giant) has been ported over from previous US Paramount releases, but you'll find no complaint here. Stevens Jnr. does most of the talking, with intermittent but always interesting contributions from Moffat, and together they deliver a fascinating collage of information on the filming and analysis of Stevens' intent and technique. Some of the more well known behind-the-scenes stories are confirmed (and quite possibly originated here – the commentary is a few years old now), and Stevens Jnr. usefully reads a few lengthy quotes from his father's personal production notes. More intriguingly, one of the most famous bits of trivia – that Jack Palace was actually terrified of horses – is effectively dispelled. As a city-based stage actor, he'd never played a cowboy or ridden a horse before, and thus spent countless hours practicing his fast draw and mounting and dismounting his horse to get it right. The claim Stevens reversed a shot of him dismounting because he was unable to confidently mount also turns out to be skewed – Stevens wanted to create the sense that Wilson's movements were cat-like, an affect he eventually achieved by reversing the film.

Neil Sinyard on Shane (22:18)

Film scholar and eloquent enthusiast for Shane Neil Sinyard delivers an enthralling overview of the film and its director, whose early career he outlines, including the impact the experience of liberating Dachau had on him and his subsequent film work. He also details some of the changes that were made to the novel when adapting it for the screen, and discusses how the critical enthusiasm that accompanied the film's release was subsequently tempered, only for the film to be later championed by filmmakers and film enthusiasts alike.

Lux Radio Theater Adaptation (53:47)

An audio adaptation of the film for the Lux Radio Theatre in which Alan Ladd and Van Heflin reprise their roles. Again a treat for completists, but robbing the film of its visuals, most of its principal cast and Stevens' direction also strips it of its poetry. Jack Palance in particular is sorely missed here, and the need to fit the whole story into half the film's running time does see it skip along at an overly hurried pace. Well worth a listen nonetheless, but the very slow zoom on the almost monotone poster will likely have plasma TV owners chewing their fingernails.

Theatrical Trailer (1:57)

Newcomers beware, as this trailer begins with the film's famed ending, and then goes one step further and includes a key part of the final shoot-out. It thus goes without saying that you should steer well clear of this until after you've seen the film.

Booklet

Rounding off this fine collection of extras is another of Eureka's always splendid booklets. This one kicks of with an excerpt from an essay entitled Shane and George Stevens by Penelope Houston that was originally published in Sight & Sound in 1953, which is followed by an enthralling 1969 interview with Stevens about the film conducted by Brazilian critic Eduardo Escorel. Next up we have extracts from Ivan Moffat's correspondence to George Stevens on the writing of the film, and a new and informative piece by Adam Nayman on the issue of the altered aspect ratio. Credits for the film, stills and viewing advice are also included.

Just recently I was talking to a media production lecturer about the technique of day-for-night shooting and remarked that it was particularly popular in the western genre, to which he nostalgically sighed and immediately quoted in the voice of a small boy without any prompting from me, "Come back, Shane!" It's hard sometimes to nail down exactly why a film works so divinely, especially given that the appreciation of any art form is always a subjective one. For me, Shane is just such a work, a beautifully realised melding of art and entertainment that is not just a cornerstone in the genre's development but also great and important cinema. I'm not alone in my opinion – Woody Allen reportedly adores it and Sam Peckinpah called it the best western ever made. Fans of the film who do not already own Eureka's superb Blu-ray release should rush out immediately and buy it – the transfer is glorious, the extra features first-rate, and the inclusion of the two alternative 1.66:1 versions of the main feature make this the most complete release that Shane is likely to see for many years. Very highly recommended.

* Intriguingly, this very same case was made with similar passion by Rancher Robert Ryan in André De Toth's 1959 Day of the Outlaw at a point where we had also been encouraged to view him as the bad guy, a film also recently released under the Masters of Cinema banner. In a somewhat tidy coincidence, that surname of Ryan's character in that film was Starrett.

|