|

Kate Davis (Chantal Contouri) is kidnapped from her home by members of the Hyma Cult, a contemporary group of vampires who live off human "blood cows" at a high-tech “dairy farm”. Kate, it seems, is a descendant of the infamous Elizabeth Báthory, and her destiny is to marry the cult leader. But first they have to persuade her of this...

Although Rod Hardy was the director, Thirst (nothing to do with other films of the same title such as Park Chan-wook’s vampire film of 2009) makes more sense as an Antony I. Ginnane production. During the Australian film revival of the 1970s, Melbourne-based producer Ginnane was intent on making a more commercially-oriented type of film, genre movies aimed at the international markets. This explains the use of overseas actors (David Hemmings and Henry Silva here) and the intentionally non-specific setting. At the time, he says, Australian cinema tended to be parochial, favouring historical- or period-set literary adaptations, which audiences would much less often actually want to pay their money to see. I would suggest that the situation is reversed now, with Ozploitation (if you could pass something off as such) being where the money is, and more likely to receive Blu-ray and UHD releases than everything other than a few standard classics. Meanwhile, some major films of the 1970s and 1980s haven’t gone past DVDs or SD streams or are currently AWOL. For whatever reason, Ginnane’s films received a critical bashing at the time, something which clearly rankles still, judging by his contributions to Not Quite Hollywood (the 2008 documentary which popularised the term Ozploitation) and elsewhere, including those among this disc’s extras. However the best films his company made stand up well, forty or more years later.

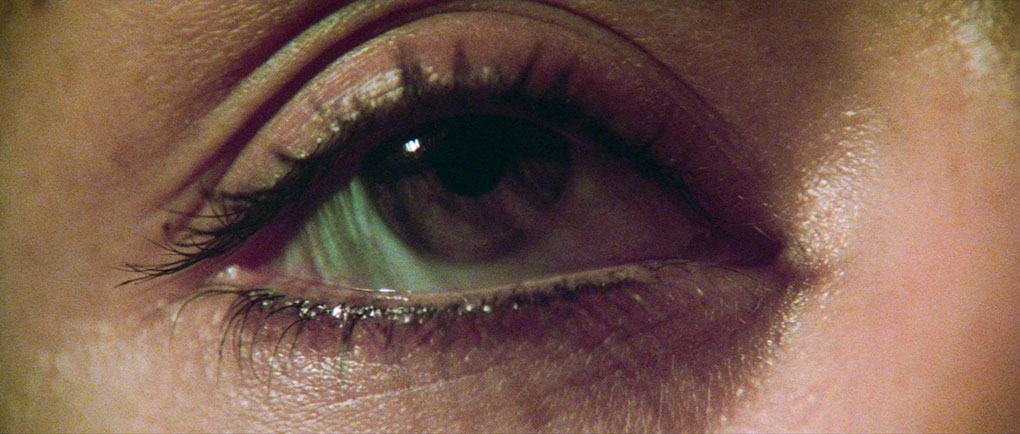

Hardy began his career in television, working for Crawford’s, the Melbourne-based company which gave early breaks for quite a few later directors. He directed many episodes of such as Division 4, The Box, Matlock Police and The Sullivans. After Thirst, he spent nearly three decades directing for the small screen, both in Australia (for example, the miniseries Sara Dane (1982), Under Capricorn (1983) and Eureka Stockade (1984)). He is the only person to have directed episodes of both Prisoner (Prisoner: Cell Block H outside Australia) and The X Files. Given the chance to work on the big screen, Hardy does a stylish job of work, helped by richly-coloured camerawork from Vincent Monton. Though much of the film is quite restrained, Hardy does pull off some showstoppers: a blood shower, a breakdown scene with furniture moving of its own accord and walls cracking and pulsating Repulsion-style, and one character's demise involving a helicopter and power lines. Brian May's orchestral score, heavy on strings with arpeggiated keyboard chords in the main theme, is another plus. Hardy finally directed a second feature for the cinema with December Boys in 2007.

From an original screenplay by John Pinkney (a journalist – this was his only cinema credit, though he did some work for television), Thirst is flawed by a narrative that follows a straight line for a little too long, leading to pacing problems in the middle section. There are however some twists towards the end. Chantal Contouri is on screen for almost all the film and certainly puts a lot of physical effort into her role. Unfortunately she's rather blank and is acted off the screen by Hemmings especially. By this time, Hemmings had become grey-haired in middle age (thirty-seven at time of shooting), but his looks were still intact and he had yet to put on too much weight. He gives an understated performance as the cult leader which effortlessly steals every scene he's in. Hemmings would act for Ginnane again in the Simon Wincer-directed Harlequin (released on Indicator Blu-ray and UHD simultaneously with Thirst) before entering into a business relationship with Ginnane. He directed some films for him, starting with The Survivor in 1981. By contrast, the other imported star, Henry Silva, has little to do but glower and look menacing. Hemmings and Silva take a back seat for much of the middle act. Further down the cast, Rod Mullinar is solid in a limited role as Kate's boyfriend. Also making an appearance is Robert Thompson, who had played the title role in Patrick: this is one of only two other feature films that he acted in, the other being Roadgames (1981) and he has dialogue this time. He died in 1984 at the age of fifty-one. As a nurse, and another Crawford’s alumna, is Lulu Pinkus, who had been in Mad Max and Snapshot and later worked with her husband Yahoo Serious on his films, beginning with Young Einstein (1988).

Thirst was shot in January and February1979, in association with both Film Victoria and the New South Wales Film Corporation. Hyma’s headquarters being the artists’ colony of Montsalvat in the North Melbourne suburb of Eltham, a popular film location. The “dairy farm” was a set built inside a former milk factory in Broadmeadows, another Melbourne suburb. Thirst opened on 2 November that year, at least in Sydney playing as the top half of a double bill with Circle of Iron (aka The Silent Flute, from a story co-written by Bruce Lee, who would have starred in it if he hadn’t died). The film was not a success in Australian cinemas but did better abroad. It did not have a UK cinema release and first appeared commercially as a pre-Video Recordings Act VHS and Betamax release in 1982. It had its first appearance on British television on the short-lived subscription channel MirrorVision (owned by the Daily Mirror, hence the name) in 1985 and received its first certificated VHS release in 1993.

Thirst is spine number 432 in the Indicator series, released on Blu-ray and UHD. This review is from a checkdisc of the former, but see below. The Blu-ray disc is encoded for all regions. Thirst wasn’t released in UK cinemas and as mentioned above was first seen by the BBFC in 1993 when it gained an 18 certificate. It was passed 15 in 2003 and retains that rating. In Australia it has always had a M rating (advisory, particularly for under-fifteens).

The film was shot in 35mm colour with Panavision anamorphic lenses and the disc transfer is in the correct ratio of 2.35:1, derived from a 4K restoration from the original negative. Over to Slarek for some words on the UHD transfer and a comparison between the two.

When comparing the Blu-ray with the UHD, the first thing that struck me is that the image on the UHD feels brighter than its Blu-ray equivalent, and I'm putting this down in no small part to the more generous contract range allowed by the Dolby Vision HDR on the 4K transfer. This also enriches the attractive, pastel-leaning colour palette, which, while pleasing on the Blu-ray, really comes ito its own on the UHD, and the red of blood is particularly vivid. Unsurprisingly, while the image is crisp on the Blu-ray, it is visibly sharper on the UHD and the finer detail more clearly defined – on the wide shot of a room at the start of chapter 10, the detail on the cushions and wicker furniture is noticeably more distinct. Thus, as you would expect, while the Blu-ray transfer is very good, its 4K brother is superior on all fronts (due to technical limitations, the screen grabs here are from the Blu-ray).

In 1979, Dolby Stereo soundtracks were beginning to be used more often, but not in Australia: the first local production to be so enabled was Mad Max 2 in 1981. So Thirst was released in mono, which to be fair was what most cinemas outside showcase venues in major cities could play. The soundtrack is rendered as DTS-HD MA 1.0. No issues here, with clarity and the balance of dialogue, music and sound effects. English subtitles for the hard of hearing are available, and I didn’t spot any errors in them. There is also the option to play the film with Brian May’s isolated score, and that track is LPCM 1.0.

Commentary with Antony I. Ginnane and Rod Hardy

This was recorded in 2003 for DVD release, so is inevitably a little out of date in some respects. Ginnane points out that this then DVD release was the first time that the film has been seen in Scope since its cinema release. Part of this was due to the New South Wales Film Corporation, one of the main investors in this film and about twenty-five others at the time, sold many of its assets to a Panamanian company. As a result many of the original materials of Thirst were tied up in litigation for years, and the making of a widescreen master proved not to be possible. More than twenty years later, we don’t know we were born. There is a rapport between the two men, which is always a positive, but this commentary tends towards the scene-specific and inevitably overlaps with other extras on this disc which were recorded at different times. A case in point...

Thirst: A Contemporary Blend (13:52)

Antony Ginnane again, this time from 2004 and another former DVD extra. Ginnane states upfront that, whoever wrote and directed the films he produced, he saw them as his, modelling himself on Roger Corman. That’s the case whether he made sex comedies (Fantasm (1976) and its suavely-titled sequel Fantasm Comes Again (1977)), family films (Blue Fire Lady, also 1977) or suspense thrillers and horror films. He is clear on the need for international actors in his films to sell them overseas, which resulted in some battles with Australian Equity. The one film where he didn’t do this, Snapshot, suffered commercially as a result. He compares the careers of his star here, Chantal Contouri, with her Snapshot co-star Sigrid Thornton and wonders if she should have had a similar career. Extracts from some of his other films are included and you may wish to be advised that two clips from Patrick feature strobe lighting.

Not Quite Hollywood interviews (39:59)

Mark Hartley’s 2008 documentary has provided many disc releases with interviews shot for that film, not always included in the final film. This is no exception. There are four of them, with a Play All option.

First is Rod Hardy (13:32). He describes how he thought John Pinkney’s script could be the basis of a spoof, but Ginnane put him straight: this was to be a film made for the drive-in market. Having worked with Contouri on television on The Sullivans, Hardy says that this was another round in having her “beaten up on screen” (she’d been shot dead previously) and he praises her commitment to the role, including her feet being cut up due to running barefoot and being drenched with ill-smelling fake blood. The scene where she receives an injection on screen wasn’t faked: she insisted that it be a genuine vitamin shot. He also compares the different characters of the two imported stars. Hemmings could party all night (and, frankly, drink too much) and turn up and be word-perfect on set the next day. Henry Silva was far more dour and serious. There was a $400 prize for whichever member of the cast and crew could come up with an ending to the film. Hardy appreciates the film’s afterlife. Once, he was working in the much-filmed location of Coober Pedy and what was on at the local cinema for that night only? Thirst.

Ginnane is next (15:11). He backs up Hardy’s recollection that Thirst was to be taken seriously and played straight, even though there was a mini-trend for horror spoofs at the time. (For example, Love at First Bite, which also came out in 1979.) He talks further about the casting of Chantal Contouri and Henry Silva, who seems to have kept much to himself while on set.

The remaining two are shorter items. Rod Mullinar (6:21) says he was originally the lead, before that role went to David Hemmings. He has some amusing anecdotes, not having found it a hardship lying “stark bollocking naked” on top of Chantal Contouri outside in a botanical gardens, but giving himself a sunburned backside as a result. He thought Ginnane and Hemmings had a “cowboy element” to them but he found Henry Silva unfunny and not especially good in his role.

Finally, cinematographer Vincent Monton (4:54) talks about how Thirst was a tough shoot for its female lead, and admits to having been starstruck by David Hemmings, even though it was clear he had a drink problem. Again, he thought that Henry Silva wasn’t really enjoying himself.

Archival interview with David Hemmings (15:55)

David Hemmings died in 2003, but he is represented here by this extract from The Don Lane Show from the Nine Network in 1979. Hemmings was in Australia to make Thirst, as is mentioned at the end. Lane’s talk show ran from 1975 to 1983 and from this extract was along very similar lines to other shows from other countries, with Michael Parkinson being mentioned. The guest is brought on and is there to tell entertaining anecdotes and that Hemmings does, particularly one where he was notably starstruck at a Hollywood dinner (in a cheap suit and tie), sharing a table with Vanessa Redgrave (with whom he had worked on Blowup and Camelot), Jean Simmons and a distinguished older woman he didn’t recognise until her name was called out, along with several other major stars. Hemmings also talks about working with Jane Fonda in Barbarella and Marlene Dietrich and David Bowie in Just a Gigolo, the latter of which he directed and which was playing in Australian cinemas at the same time as Thirst. Clips of both are shown. This item looks like it is derived from a homevideo recording, as there are tracking errors now and again, though Indicator have overlaid captions over the film clips.

Archival audio interview with Chantal Contouri (23:48)

Also from 1979, this time from 2SER radio, Contouri is interviewed by Michael Fitzhardinge. This is more a career overview than anything specific to Thirst, which was in cinemas at the time. It begins with her first appearance on television, locally in Adelaide, in 1962 at the age of twelve, singing “Silent Night” in Greek. Also discussed is her stint on the notably taboo-breaking small-screen drama series Number 96. She certainly takes few prisoners. The name of the special effects artist on Thirst she blames for getting things wrong is deleted (presumably on the original broadcast, not by Indicator), someone she says left her with acetic acid burns on her hands. It’s not hard to work out who is being referred to regarding Snapshot: the suburban-dwelling director who didn’t believe characters like hers, bohemian and not forgetting gay, really existed. In fact, she has no time for that film at all, calling it dreadful apart from the cinematography, music and editing. At the time of interview she was about to act opposite Wendy Hughes in Friday the Thirteenth, but given what other film with that title came out in 1980 you can understand why this film had its title changed. It would see Australian screens as Touch and Go.

Film Buffs Forecast: Rod Hardy (154:01)

This is an episode of Paul Harris’s Film Buff Forecast podcast which was released on 21 January 2019. He was joined by Not Quite Hollywood director Mark Hartley. Together they interview Rod Hardy and as you can guess from the running time, it’s an extensive chat covering his life and career. If you want to listen to them discuss Thirst, go to the forty-seven-minute mark. They begin with Hardy’s upbringing in Fitzroy (Melbourne), with his love of film being sparked by frequent visits to the Regent Cinema nearby. Watching young Colin Peterson in Smiley (1956) led him to think “I could do that”. Leaving school, he first worked in radio, but ran in a street gang (The Sharpies, named after their fashion sense) out of hours, which resulted in a three-month prison sentence and the loss of his job. While he was in jail he often heard his own show on the radio. Later, he auditioned for Crawford’s, being taken on as a music editor on such shows as Hunter and Homicide. He was directing before he turned twenty-one, with an intense production schedule on some shows meaning that five half-hour episodes were made a week. Antony Ginnane recruited him from Crawford’s to make Thirst. They didn’t work together again, with Hardy claiming Ginnane owed him money and giving a few examples of the latter’s penny-pinching. While at the time cinema was more prestigious than television, that wasn’t necessarily so in the case of exploitation films like Thirst. Hardy continued to work on the small screen in the 1980s, a good time for prestigious miniseries, many made in South Australia. Harris and Hartley also talk of some feature films that got away, including An Indecent Obsession (which was eventually directed by Lex Marinos and released in 1985) and Hating Alison Ashley (directed by Geoff Bennett in 2005).

Seeing Reality (3:36)

A short interview with stuntman and stunt coordinator Grant Page, which plays as audio over the relevant clips from the film. He discusses the staging of the helicopter stunt from near the end of the film.

First Blood (17:56)

Dr Stephen Morgan continues his appreciations on Indicator’s Ozploitation releases. For a general overview of Ozploitation, see his piece on the Patrick disc as material there has not been repeated on later pieces. He begins by saying that the history of Australian vampire films is a short one, though Thirst was not quite the first example. (Donald Pleasence played Count Plasma in Barry McKenzie Holds His Own (1974).) There haven’t been many since: Morgan mentions Colin Eggleston’s TV film Outback Vampires (1987, his final film and a favourite of Quentin Tarantino’s), the Spierig Brothers’ Daybreakers (2009) and the streaming series Firebite (2021/2), co-created by Warwick Thornton. (There was also the 2002 Australian/US coproduction Queen of the Damned, which also used Montsalvat as a location.) Morgan talks about the circumstances of Thirst’s making in 1979. It was a beneficiary of the 10B tax incentive, though that meant that it had to be completed by June to qualify. It was in post-production at the same time as Mad Max in the same facility. Morgan gives a run-through of the principals on both sides of the camera, in a useful piece best watched after the film if you haven’t seen it before.

Trailers and TV spots (5:47)

Five items, with a Play All option. There are the Australian theatrical trailer (2:55), the more concise US version (1:36) and three US TV spots (0:11, 0:31, 0:32).

Image galleries

There are three, all navigable by the forward and back buttons on your remote. The first is of promotional material – 109 images, with ten black and white and eighty colour stills, a promotional picture of Henry Silva, the press kit, a magazine cutting announcing the film’s production and some poster designs. “Behind the Scenes” features 127 stills, twenty-seven in black and white. Then there is the dialogue continuity script, eighteen pages.

Book

Indicator’s book with this limited edition (6000 UHDs and 4000 Blu-rays) runs to eighty pages. We begin with “Insatiable Thirst” by Diane A. Rodgers. She is a specialist in folk horror and that’s the angle she begins this essay with, wondering which themes and lore are being used in this particular take on the vampire film. Hyma is reminiscent of real-life cult activity of the previous decade and more (the Manson Family, for example) but in the film is more of a metaphor for the upper classes being parasitic on the lower ones, who are being literally milked for their blood. The pressure is on Kate to conform to this. As Rodgers points out, it’s nearly half an hour, a third of the film’s running time, before we see anything approaching traditional vampire lore in Thirst and the traditional methods of dispatching them are nowhere to be seen, and the vampires even show up in mirrors. Only the glowing red eyeballs hint at anything supernatural.

As with the booklets for Patrick and Snapshot, next up is an extract from Antony Ginnane’s unpublished autobiography Some Scenes Objectionable. He liked John Pinkney’s script and saw the opportunity to make a vampire film in a contemporary setting, especially as Hammer’s vampire cycle had run its course by then. He paid David Hemmings more than he had paid any other actor to that date, but then Hemmings was a star. However he was prone to agreeing to work due to being often short of money. Donald Pleasence was also considered, but his success in Halloween had made him too expensive, so that role went to Henry Silva. After the film went into market at Cannes and MIFED in 1979, it opened in Australia to disappointing results but the film sold abroad, to New Line in the USA. As before, this is long and detailed and a little dry, but as informative as it needs to be.

Chantal Contouri is next, interviewed in the USA for the Omaha World-Herald in 1980. With Thirst yet to appear in a local cinema, this piece covers her life to date. This begins with her being born to a twelve-year-old mother in Corfu in 1950, the eldest of what would be five children. The family emigrated to Australia four years later. She married a sailor at age sixteen in order to get away from home, a marriage that lasted just three days, and she took various jobs while always wanting to be an actress. She ends with a few words about her new film.

David Hemmings is next, interviewed in 1979 for Cinema Papers by Ross Lansell. This begins by talking about his directorial debut Running Scared (1972), influenced by Antonioni and more European in style than many British films of the time. His next film, The 14 (1973) was more successful, though had less critical support. A year before this interview, he had made Just a Gigolo in West Germany, though he left the film and it was recut by others. He was disappointed by the results though does defend parts of it, including David Bowie’s performance. He then talks about the state of the film industries in the countries he’s working in, beginning with the UK (not enough good screenplays and a lot of people working on television). He talks about the forthcoming production with Antony Ginnane, Race for the Yankee Zephyr, which Richard Franklin was to direct and Hemmings was to take a “back seat” on. As it turned out, he ended up directing it himself, in New Zealand rather than Australia. There is much on the financing side of film production and the realities of making films in Australia. This is a lengthy and detailed interview, clearly pitched (given the magazine it was in) at an industry rather than general readership.

This is followed by “A Model of a Bad Guy”, a brief piece by Deborah Forster about Henry Silva from Melbourne’s The Age in 1979. A New Yorker of Sicilian and Spanish descent, he played a variety of nationalities, in the present case German. He says he has yet to make his favourite film but enjoyed Buck Rogers in the Twenty-Fifth Century (1979), in which he played another villain.

Also in the book are transfer notes, a cast and crew listing and plenty of stills.

Although it certainly has its flaws, Thirst has its moments of interest as well, as an example of where the Australian film industry was at the time, and a rare foray into the vampire genre. Released in both UHD and Blu-ray, Indicator’s disc presents the film as well as their other Ozploitation releases.

|