| |

“While other directors frame their action sequences by way of intricately choreographed bullet ballets, relayed in disorienting flurries of close-ups and rapid edits, Kitano kept the viewer distant and detached. His scenes unfolded sedately in immaculately composed long shots, building a dread sense of anticipation before exploding into violence with only the scantest of warnings.” |

| |

Jasper Sharp – Where to begin with Takeshi Kitano* |

I have a feeling that anyone approaching a review of a Blu-ray box set titled Takeshi Kitano Collection today will already be at the very least familiar with the name of the actor-director whose films are contained within and hopefully will have seen at least one of his films, possibly more. For the uninitiated, I’m going to kick things off with rewrite of the introduction from my coverage of Second Sight’s 2008 Kitano DVD box set, and also explain why I use the Japanese naming convention of family name first in my reviews of Japanese films.

In Japan, Kitano's media fame was considerable even before he began directing movies. Starting out as one half of The Two Beats, a successful manzai comedy duo (a uniquely Japanese style of stand-up that involves almost unbroken quick-fire verbal exchanges between two, or occasionally more, performers), his CV later expanded to include TV comedy performer and show presenter, actor, newspaper columnist, author, poet, painter and film director, writer and editor. Previous to this he had also been a boxer and a tap dancer. Years later he was still able to tap dance – on one of my earlier visits to Japan he paused the humour on one of his many TV appearances to impressively demonstrate that he'd not forgotten his moves.

His first directing gig on the 1989 Violent Cop [Sono otoko, kyōbō ni tsuki] came about almost by chance when veteran filmmaker Fukusaku Kenji was unable to helm the film as originally intended, apparently due to problems created by Kitano’s busy working schedule, and Kitano was offered the chance to direct the movie in his place. Despite completely rewriting the script and taking an improvisational approach to dialogue, he delivered the goods with some style, and a new career for Kitano began. It’s been theorised that his early films weren’t big hits in his native Japan because he was known there primarily as a comedian and thus not taken seriously as a filmmaker or a dramatic actor. Only later, when his 1997 film Hana-bi won the prestigious Golden Lion at The Venice Film Festival did audiences really start to take him seriously in Japan, but by then he was already starting to make an impression in the west, where few of those taken by his films were even aware of his former comedy career.

Yet just five years after the release of his debut feature, it nearly all came to a tragic halt. In August of 1994, shortly after the completion of his first all-out comedy film, Getting Any? [Minna Yatteruka!] and his acting duties on the film adaptation of William Gibson's Johnny Memonic, he was involved in a serious motorcycle accident that left one half of his body partially paralysed. A number of surgical procedures were required to restore a degree of facial movement, and for a while it looked as if his glory days were well and truly over – I remember a friend in Japan telling me that in his first TV appearances following the accident he seemed like a shell of his former self. And yet, fewer than two years later he completed the autobiographical Kids Return, one of his most captivating films and his biggest success yet on home turf. It was also following the accident that he took up painting, a therapeutic vocation that made its way into his Hana-bi, which also marked his return to screen acting. In what seemed like no time at all he had re-established himself as Japan's busiest and most prominent media figure.

I first discovered his work as a director through his fourth film, Sonatine, and quickly became something of a Kitano junkie, recording his movies on VHS (remember that?), tracking down DVDs when the format took hold and arranging local cinema screenings of any of his films that secured a UK release. From A Scene at the Sea [Ano natsu, ichiban shizukana umi] onwards, all of his films were made under the umbrella of his own production company, Office Kitano, which quietly became involved in the production and distribution of a number of other international works – scan the end credits of Samira Makhmalbaf's Blackboards [Takhté siah] (2000), for example, and you'll find a targeted thank-you (though in 2018 Kitano quit the company he founded to go completely independent). He has also elected to make a clear distinction between his roles as writer-director and actor, going under his real name on his filmmaking credits but his stand-up comedy name of ‘Beat’ Takeshi when acting, at least in his own films.

Which brings me to the business of Japanese naming conventions, which the conflict between the title of this box set and how Kitano's name is written in this review has prompted me to discuss. For those who do not know, in Japan the naming convention is family name first, given name second, thus if David Lynch was Japanese his name would be Lynch David, to pick a random example. In the west we do the reverse and so tend to swap the natural order or Japanese names around in order to conform to what we regard as the norm. Curiously, there is a degree of inconsistency to this habit – this year the Academy Award for best picture went to a Korean director you might just of heard of named Bong Joon-ho, and yet Korea has the same naming convention as Japan, and Bong is his family name and Joon-ho his given name. It’s the same story with Chinese names and a certain Wong Kar-wai. So why is it Bong Joon-ho and Wong Kar-wai and not Kitano Takeshi?

For many years now I’ve been using the naming conventions of the country from which the filmmakers or actors under discussion hail rather than the western default of surname last, only opting for this if I am unsure of what the convention in question for that country actually is. I’m particularly strict on this when it comes to Japanese names, and as that puts me at odds with the vast majority of UK and US reviewers, I think it's about time that I outlined why. My reasons are two-fold. The first and most obvious one is that I have great respect for Japan and its culture and don’t see why the Japanese should have their names reversed just because their naming convention is different to ours. It reeks of a sense of superiority on our part, that our way is somehow better than theirs and that they should jolly well sort themselves out and do things more like we do. Bollocks to that. Having said that, I do get the thinking behind this, that if you aren’t aware of this convention then you might genuinely not know which name is which or even what to call the person standing in front of you. I’ve thus attempted to clarify my usage of this convention within reviews of Japanese films by adding a note at the bottom to the effect that I have done so. My second reason is the simple one of name familiarity. My partner is Japanese and we’ve been together for some time, and when discussing any filmmaker or actor from her home country she naturally uses the Japanese convention, and thus for some years now I have gotten used to doing likewise. To give weight to my decision I should note that back in May of 2019, Japanese Foreign Minister Kono Taro specifically requested that western media organisations use the family name first when writing Japanese names, noting, as I suggested above, that they often already do so with Chinese and Korean names.**

That said, I’m not going to start changing the titles of disc releases, box sets or special features in my reviews to conform to the convention I have chosen to observe. Thus, when I refer to this box set in the review I will do so by its published title, but when I refer to Japanese actors or filmmakers I will identify them by the name they were given in their country of birth, which is why in this review of Takeshi Kitano Collection (the definite article is not part of the title), the actor-writer-director’s name will be written as Kitano Takeshi. That said, I still get occasionally tripped up, as with the semi-western sounding Joe Hisaishi, which I only relatively recently discovered was indeed Hisaishi Jō, a name apparently chosen by the composer (whose birth name was Fujisawa Mamoru) because of its similarity to the Japanese translation of the name Quincy Jones. Oh, and one last thing. There are a small number of actors in Kitano’s early movies who work under a single stage name, such as Hakuryū, who plays Kiyohiro in Violent Cop. Thus when you see these, it’s not because I’ve forgotten to include one of that actor’s names.

This box set consists of three of Kitano’s first four films as director, in all of which he also either stars or features – his auspicious debut, Violent Cop, his often underrated follow-up, Boiling Point, and his magnificent inversion of the traditional yakuza thriller, Sonatine. Missing from the set and made between Boiling Point and Sonatine is the 1991 A Scene at the Sea, but worry not, as this is already available on Blu-ray from Third Window Films and comes highly recommended. As a final note, the reviews for Violent Cop and Boiling Point have been updated from earlier DVD coverage, whilst my opinions on Sonatine are new to this release. Any dialogue quoted is taken from the subtitle translations included in this set.

| VIOLENT COP [SONO OTOKO, KYŌBŌ NI TSUKI] |

|

I'm always a bit of a sucker for films that open on a facial close-up. It goes against conventional scene construction wisdom, which favours establishing the location and situation before introducing the characters, hence the use of term 'establishing shot' for scene-opening locational wides. Start your film on a facial close-up and you’re asking your audience to quickly connect with someone they've never met and know nothing about, then absorb the who, where and why as the scene or even story unfolds. But it's this very break with convention that can provide a film with an instant aura of intrigue and suggest from the off that it is unlikely to play by the usual rules.

The face in question here belongs to an unnamed homeless man (his status is established by his weatherbeaten face, missing front teeth and plaster-repaired glasses), a minor character whose only narrative function is to introduce us to the singular working methods of the cop of the film's international title. Two shots in, as the man tucks into what passes for a meal, he is set upon by three youths for no other reason than it amuses them to do so, much like Alex and his Droogs in Stanley Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange. Having kicked him unconscious, the three cheerfully head off to their respective respectable family homes. No sooner has one of them walked inside than seasoned detective Azuma arrives at his door and asks to speak to him, politely requesting that his confused mother waits downstairs while he does so. When the boy petulantly responds to the repeated knocks on his bedroom door, Azuma punches him in the face, slaps him violently across the floor and advises him and his friends to turn themselves in the following day. Unsurprisingly, they do just that, but Azuma still gets a lecture from officious new Chief Detective Araki (Hamada Noboru), who is only too aware of the detective's reputation. "I can’t say I’m against it, were it not my job," he says of Azuma’s actions, "But behave yourself for a year while I'm chief, won’t you?" Somehow you doubt this is going to happen.

There’s not much ambiguity to a title like Violent Cop, but then this is not the film's original title but the one given to it for its international release. The Japanese title is Sono otoko, kyōbō ni tsuki, which translates, as near as a dammit, as 'That man, he is dangerous', and we're talking a specific kind of dangerous for which there may be no equivalent English word. When trying to explain to me the true meaning of the kyōbō of the title, my partner pointed to amoral hit man Anton Chigurh in No Country for Old Men as a good example, which suggests the English substitution of the word 'violent' doesn't really go far enough. Then again, it’s also quite possible that the dangerous man in question is not Azuma but sociopathic hitman Kiyohiro (Hakuryū), against whom Azuma is ultimately pitted. Some time before the film ends it seems possible that it might refer to both.

Maverick cops have been a global movie favourite for a good many years, non-conformist individuals who are prepared to tear up the rule book and plough a furrow through convention to apprehend the criminal who would otherwise escape the justice he's clearly asking for. Invariably they are a the product of the political right, the physical manifestation of a belief that a bureaucratic liberal system favours the criminal over the victim and that the only real way to get justice is to let a lunatic loose with a massive gun. That such characters have proved popular with a mass audience is not all that surprising, as there can be few who haven't found themselves in a situation at one time or another where their anger and frustration at the actions of others has not stirred in them a desire to deliver their own, very specific brand of justice. These characters are the embodiment of that often deeply buried desire, conscience-free rule-breakers with the authority to kick ass and the necessary ruthlessness and disregard for their own safety to do so to the extreme. Oh if only it was anything like that simple. Such figures have a long history in crime fiction and an even longer one in westerns, where a maverick sheriff really could be up against an almost lawless society controlled by very bad men. But it's in modern crime cinema that the character has really found an audience, one that (sometimes unconsciously) seems to share the filmmakers' despair both at changing times and revisionist cynicism regarding the traditional, usually male hero figure. Moral issues regarding the character's behaviour are usually (over-) simplified by making the villains unspeakably evil and having them laugh in the face of authority and those they had wronged. In 1971 this gave birth to 'Dirty' Harry Callahan, without question the most famous of all modern maverick detectives and the template for those that followed in his wake. It's surely no coincidence that the actor who played him came to international fame as an amoral western antihero.

Despite the cultural and location shift, the shadow of Eastwood's cop can be keenly felt in Violent Cop and in the character of Azuma in particular. Both men establish early on their brutal approach to justice, both are warned by their respective bosses and about their excessive working methods, both have a long-standing relationship with a fellow detective (in this case the almost businessman-like Iwaki, played by Hiraizumi Shigeru), both are partnered with an eager rookie (a regular component of the Dirty Harry series), both torture their suspects to obtain information and see them walk free as a result, and both are driven to extreme action by the activities of the criminals they are pursuing. But it's those above-mentioned cultural differences that differentiate Kitano's film from its American birth mother and give it its own specific identity. Where Callahan's approach to bad guy apprehension is established with the foiling of a bank robbery and "the most powerful handgun in the world," Azuma's is cemented through the brute force of physical assault, all the more shocking because it takes place in the young offender's bedroom in (presumably) full earshot of his mother. Where Callahan's contempt for authority is made clear through his argumentative back-chat and smart remarks, Azuma shows his through silent indifference (when told the new chief wants to see him, he simply nods and returns to his newspaper) and the motionless stares he offers as a response to the criticisms of his superiors.

A key difference between the two films is one of scale. The crimes that trigger Callahan's extreme response are headline stuff, with the character-defining armed robbery giving way to a Zodiac-influenced serial killer with a particular hatred for the police and Callahan in particular. Azuma's punishment, on the other hand, is dished out to more everyday criminals, the hoodlums of the opening scene and a mouthy young punk who abuses his girlfriend and whose attempts to get tough with Iwaki land him a brief but brutal kicking from Azuma – only later does he get to directly confront a genuinely sinister villain in the shape of the amoral Kiyohiro. Like his American counterpart, Azuma has no wife or girlfriend to soften his alpha male standing, though he is taking care of his mentally troubled sister Akari, on whom he clearly dotes. It's a task he carries out with the same ruthlessness as his day job, dishing out an extended kicking to a young man foolish enough to take advantage of the girl’s emotional vulnerability.

Where the film comes into its own is in its handling and tone, which is striking in part for how it differs from the American model, but also because of how it defines several aspects of what would become the distinctive Kitano style. Certainly the film's importance in modern Japanese film history lies in its status as the ex-manzai comic and all-round media workaholic Kitano’s first feature as director, a job that he only landed by chance. Watching the film from a modern perspective you can certainly see the Kitano style starting to take form, in the use of long takes and character stillness, in the sudden and unexpected explosions of violence, in the compression of action into two static shots and a perfectly timed edit, in the stoic moments in Kitano's performance, in the sometimes unconventional frameing and in the lingering shots of the ocean, a signature feature of Kitano’s cinema. There's even a small role for Kitano’s close friend Terajima Susumu, his brief appearance as a gang member here giving no hint of the significant roles he would go on to play later Kitano films. And although Kitano is two films away from his first teaming with regular composer Hisaishi Jō, the use of music here is as wedded to the imagery as in any of his later works, with composer Kume Daisaku’s rearranging Erik Satie's Gnossienne No.1 for the main theme, and dreamily counterpointing a long chase scene with lounge jazz rather than augmenting the pace in the traditional manner.

In Azuma you can see elements of a number of later Kitano tough guys, from yakuza boss Murakawa in Sonatine to the loud indignation and blather of Kikujiro’s title character. A key component is Kitano's distinctive gangster walk (one he himself has rather uncharitably described as being like a duck's waddle), which has the confident but untidy swagger of a man who doesn't have to walk at all, one whose lumbering but purposeful momentum seems designed to publicly announce the threat he represents, a coiled spring of potential violence kept in check by world-weariness. It's an image that was to later find it's perfect vehicle in Sonatine's Murakawa, a yakuza general who is genuinely tired of the gangster lifestyle and for whom brutality and murder are almost instinctive acts.

The film is further distanced from its western cousins by the unrestrained physical brutality of its violence. When suspects are slapped here the blows make real contact and are repeated far beyond the point you'd think even the most dedicated actor would be prepared to tolerate. Just occasionally this develops a darkly comic edge, as with the young man Azuma finds in his sister's bed, who amusingly bumbles out flustered questions about where to catch a bus as he struggles into his clothes, only to be kicked down the stairs by the calmly unemotional Azuma, a second blow ramming his head into an iron railing in what looks very much like a for-real injury. The detective then escorts the hapless man to the bus stop, kicking him repeatedly as he questions him about his intentions towards his sister. Probably the single most violent moment owes its teeth-gritting impact as much to the filmmaking as to the action itself, as a clumsily desperate grapple between a detective and a fleeing criminal is given almost balletic grace by the music and the use of slow motion, only to be brought to a sudden and shocking halt when a baseball bat makes contact with a head, and the sound and vision switch abruptly to normal. Such inventive handling is not isolated to this one scene – a later confrontation between Azumi and Kiyohiro involving an attempted stabbing, a head-butt and a stray bullet remains one of the most startling sequences in Kitano's entire oeuvre.

Where the film does fall a little foul of convention is in Azuma's final act push towards retaliatory violence, the reasons supplied being as extreme as those in any number of Hollywood action thrillers, though the aspect most personal to Azumi does go places that American cinema of the time would have likely shied away from. Compensation is provided by the aplomb with which the whole thing is staged, two genuinely startling gunshots (one shocking for the moral implications of the act), and the reaction of newly promoted yakuza boss Shinkai (Yoshizawa Ken), who contemplates the carnage before him in disbelief and mutters disbelievingly, "They’re all mad."

Violent Cop plays both to and against generic expectations, a cultural and artistic re-interpretation of formula that plays for the most part like a true original. Some years ago I remember seeing an interview with Quentin Tarantino, himself a major fan of Kitano’s cinema, in which he was attempting to explain exactly what it was that made Jean-Pierre Melville's Le Samourai such a uniquely extraordinary work. He identified the locale and cultural interpretation as crucial elements, suggesting that essentially what Melville had done was take elements from American genre movies and transpose them to modern Paris, then adding with typical Tarantino excitement, "but that made all the difference!" Such is very much the case with Violent Cop. And how.

| BOILING POINT [3-4 X JŪGATSU] |

|

Kitano's second film as director opens, like its predecessor, on a facial close-up. This time, however, it's not to set up a minor character but to introduce the lead, a quiet teenager named Masaki (Yanagi Yūrei, who is credited here as Ono Masahiko). This first silent encounter is then revealed to be taking place in an unlit cabin toilet a couple of hundred metres from a local baseball field. A seemingly inconsequential image, it proves to be hugely significant for reasons that won't become apparent until the film’s end, which makes it damned difficult to talk about without spoiling things for newcomers. I will get to it – it poses too many questions be ignored – but the discussion will come with a warning so that first-timers can bypass it until they've been properly primed by the film itself.

Masaki, we soon learn, is the weakest player on a local junior baseball team, a pinch-hitter who seems to get struck out every time he steps up to the plate. If that sentence made little sense then there's a good chance you're neither American nor Japanese and know little about baseball – I certainly had to do a quick bit of research to find out that a pinch-hitter is a substitute batter. It's doubtless the non-universality of baseball terminology that prompted the international title change from 3-4 x jūgatsu – literally '3-4 x October', a reference to both the final score of the second in-film game and the month in which the best games are played – to Boiling Point, which while less esoteric is no more suggestive of developments to come than its semi-numerical predecessor.

Anyway, back to the story. Masaki works at a garage that is visited one day by a cocky young yakuza, who expresses his dissatisfaction at the service offered by humiliating Masaki and smacking him in the mouth, something Masaki eventually responds to by taking a swing back. This lands him and his employer in the bad books of local yakuza boss Otomo (Igawa Hisashi), whose lieutenant Muto (Bengaru) is nonetheless impressed enough with Masaki's nerve to suggest that he join them, an offer the boy doesn't respond to either way. As it turns out, the baseball team manager and local bar owner Iguchi (Iguchi Takahito) is an ex-Otomo yakuza of some standing, and he decides to try and help Masaki make peace with the gang. When Otomo scorns Iguchi's civilian status, however, Iguchi gets him alone and beats him senseless, which later results in him taking a retaliatory pasting from the rest of the gang. When the laid-up Iguchi announces his intention to go to Okinawa and buy a gun to take revenge on his former comrades, Masaki volunteers to go in his place. Once there, he and his friend Kazuo (Iizuka Minoru), who elects of a whim to go with him, are befriended by a semi-psychotic yakuza bully named Uehara (Kitano) and his lieutenant Tamagi (Tokashiki Kaysuo), and soon find themselves drawn in to a dark and dangerous world.

Important though the plot is, much of the screen time in Boiling Point is devoted to character scenes, with narrative advancement occurring in the blink of an edit, a moment of conflict, or a seemingly throwaway line of dialogue. In typical Kitano fashion, there are a number of sequences that appear to have been included primarily for the fun of staging them, but almost all have echoes in later scenes, repeating imagery and actions or lessons that are learned and put to sometimes unexpected use elsewhere. A couple of these scenes will probably need an appreciation of baseball to justify their length and easy pace, while others are clearly designed to drive home just how unpleasant a creature Uehara is and how deserving his punishment will be when it inevitably arrives. Almost all are character-driven and many raise interesting questions about the back story of the person in question. This is particularly true of Iguchi, whose decision to leave the yakuza appears to have left him internally conflicted, seemingly successful in his adaption to civilian life but whose history of violence and former position of power and respect can still prompt extreme responses to any verbal wound to his pride.

Stylistically and tonally, the film sees Kitano fine-tuning the elements and techniques first explored in Violent Cop and in the process drawing up a partial stencil for the films that would follow. Reaction shots are often static and motionless, violence can strike anyone and explode out of nowhere, and silent pauses are as telling as the action that precedes or follows it. It’s also here that Kitano's signature before/after editing technique is first employed for comic effect, when the cocksure new owner of a high-powered motorbike scorns the idea of a wearing a helmet and tears off on the machine, and the film cuts immediately to his shocked and bloody face following his inevitable collision with another vehicle, one that is neither seen nor heard within the film itself. There's even a beach baseball scene that directly prefigures the seaside game-playing of Sonatine, one whose almost invisible switch from slow-motion to real time echoes a fight scene in Violent Cop and would be reworked in Kikujiro and Hana-bi.

Intermittently, there's a blackly comic edge to the violence, as with the car packed with jeering youngsters that ploughs unexpectedly into a parked vehicle (a stunt done for real with the actors on board), or the machine gun hidden in a bunch of flowers that unexpectedly discharges and startles everyone in the room, including the person holding it (Kitano's bemused reaction here is priceless). Best of all is an impeccably choreographed, single-shot, handheld barroom sequence in which Uehara responds to the verbal abuse of a yakuza rival by smashing a beer bottle over his head, and when the man’s companion jumps to his feet his is given a swift beating by Tamagi, one he only briefly pauses his dancing to administer. Amusing in itself, becomes even funnier when the whole thing is immediately repeated with the same result. There's even a light-hearted sequence in which the boys calmly smuggle a handgun onto an commercial flight, one almost guaranteed to widen eyes in disbelief in the post 9/11 world. Notably less comical is an earlier bar-room assault in which Iguchi politely tolerates the scornful mocking of a group of youngsters before viciously braining one of them with a glass ashtray, Any satisfaction at seeing spoilt brats put in their place is tempered by the fact that the victim is a teenage girl rather than a hard-nosed hoodlum.

While the pace remains characteristically even throughout, the film differs from other early Kitano features in the tonal shift it undergoes once Uehara joins the story. Played by Kitano himself in what is effectively a supporting role, Uehara is far and away the most unpleasant and unlikeable character he has portrayed in his own films, a demented and amoral bully on a warped power kick who misses no opportunity to hurt or humiliate others, including those he is nominally close to. His first screen appearance sees him being quietly balled out by the yakuza hierarchy on charges of embezzlement, which he responds to by grabbing a bottle to attack his accusers and is only prevented from doing so by the guns that are quickly pressed against his temple. A short while later he's outside the venue, repeatedly kicking the bodywork of a gang car like a petulant kid until the inevitable fight breaks out between him and its minder. The degree of abuse suffered by the loyal but long-suffering Tamagi – from having his finger cut off as an offering to the yakuza bosses (a sequence that should have all but the insensitive wincing, despite its non-graphic nature) to being raped by his boss – makes you wonder just what the source of that loyalty is. Twice Uehara lecherously comes on to the terrified Kazuo (sticking his face in the boy's crotch, he flashes him a wide grin and tells him he smells nice, then kisses him on the cheek), and he manufactures a reason to get mad at girlfriend Fumiyo (Fuse Eri) by ordering her to have sex with Tamagi, then spends the next few hours repeatedly slapping and kicking her for doing so, to the point where there will be few watching who don't want to take a swing at him themselves.

Until the final scene, Masaki plays a largely passive role in his own adventure, a position that is largely forced by circumstance. A boy of few words at the best of times – nods and affirmative grunts often stand in for vocal responses – his silence in Uehara's company is likely the result of youthful fear (an easy one to understand and share, as it happens), while his lack of communication on the baseball field stems at least partly from his embarrassment at his own ineptitude and the derision it provokes in others. Even his one moment of baseball glory after productive hours of practice bat swings is ruined by his disassociation from the world around him, a game-winning home run disallowed because he overtakes his frustrated teammate.

Which brings me to the bit that you really shouldn't read unless you've either never seen the film or have absolutely no plans to do so (and if so, why on earth not?). The following paragraph is all about how the film ends, so seriously, if you're new to this film yet then skip to the final paragraph and come back here later with your own opinion about what it all means. Of course, if you know the film then you'll probably already have your own views on this – I'm covering it in purely the in the interest of throwing a few possible interpretations into the pot for consideration. Feel free to suggest your own.

To put it simply, the film ends just as it begins, with Masaki in the darkness of the baseball field toilet, from which he then emerges to return to the game. As an ending it's inconclusively suggestive and open to a number of possible interpretations, particularly in light of the scenes that immediately precede it. The most straightforward is that, following his adventures, Masaki has returned to normal life and will deal with the consequences of his actions when they arise. Frankly, this seems unlikely, requiring us to swallow the notion that our boy did not die in the fireball he unleashes on the Otomo company and that he somehow jumped free before the lorry he was driving ploughed into the building. Sorry, no sale. The second possibility is that the whole thing is a flash-forward to future events, one that at its conclusion returns us to the story's beginning, where the central protagonist emerges from the toilet with little idea of the dramatic direction his life is soon to take. Hmm, even the first one seems more likely than that. The third and most potentially contentious is that the whole thing has been a daydream, concocted in the dark of the toilet by an unassuming nobody who fantasises about adventures beyond his experience and capabilities. This is given some credence by Masaki's expressionless observation of events that happen largely around him rather than to him, the fact that Uehara's worst behaviour is directed at everyone else, and a climax that sees him sacrifice his life in the name of righteous vengeance by driving an explosive fuel truck into enemy headquarters with a girl he’d probably never have the gumption to ask out at his side. This take on events is given some credence in the opening scene when Iguchi asks Masaki why he spends so long in the toilet – daydreams this detailed, after all, take time to formulate. If this works for you then it seems likely that this fantasy was constructed from actual memories, perhaps sparked by a genuine dressing down received from a cocky garage customer that Masaki desperately wanted to hit but would never have the nerve to, the rest drawn from stories told by others and casual friendships that could have developed into something more. It’s certainly the one I went with on my first few viewings, but watching it again, perhaps with with a keener eye, I noticed a small detail that caused me to question this take. When Masaki leaves the toilet at the start of the film he ambles slowly towards the baseball field, but as the credits roll at the end his jogs towards it, his movements and expression somehow more positive, as if he has undergone a transformation. Maybe that first explanation isn’t so far-fetched after all.

Back when I first saw Boiling Point I was surprised by the fact that some fans of the director's work seemed to be less keen on it than they were on the films that preceded and followed it (it still has the lowest user score on IMDb of his first quartet of films), with comments to the effect that it is structurally ragged, unfocussed and even a little confusing. It's a view I've never shared nor really understood. For me, Boiling Point is all about Takeshi exploring and shaping his directorial identity, experimenting with storytelling, scene construction, filmmaking and character definition and interaction, in the process fine-tuning elements that would come to define the his cinematic style. It's littered with offbeat characters and encounters that don't always tidily connect but are fascinating in themselves, from the train passenger who asks Masaki and his girlfriend Sayaka (Ishida Yuriko) directly about their sex life then persuades them to go fishing with him, to a varied cast that includes an American army gun-runner and a black female hostess, a rare character to find in Japanese cinema of any period. In this respect it could be argued that Boiling Point plays more like a gorgeously detailed sketch book than a completed painting, but it's one littered with exciting and imaginative artwork and in which all of the elements for future masterpieces are most vividly drawn.

Sonatine was my introduction to Kitano Takeshi the filmmaker and a film that genuinely changed my life. I probably need to clarify that statement. In the years leading up to my first viewing of the film I had developed a fascination for Japanese culture and a growing love for classic Japanese cinema. I had even started attending Japanese language classes, though dreams of one day visiting the country were held back by the need to board an aeroplane to do so, something that terrified me and that had I so far successfully avoided doing. I was aware of Kitano the actor through his pivotal role in Oshima Nagisa’s extraordinary prison camp drama, Merry Christmas Mr. Lawerence, but knew nothing then of his background as a comedian and TV personality. I can't remember the exact year, but I seem to remember that the BBC were marking the centenary of cinema by screening 100 films to represent the diversity and creativity of the medium, albeit 100 films that they had secured the rights to show. Almost every title on the list I knew and had seen or had at the very least heard of. All except one. The film was was Japanese and unlike most of the titles on the list was a relatively recent release. I thus tuned in eagerly. I was utterly blown away.

The impact on my life was considerable. It proved to be a significant step in transforming my fascination with Japan into an all-out passion. I immediately began seeking out any examples of (then) modern Japanese cinema I could lay my hands on and it proved to be the kicking-off point for a love affair with Kitano’s cinema. Most significant of all, it was instrumental in convincing me that my dream of visiting Japan should be turned into a reality, ultimately pushing me to confront my fear of flying and actually go there. First flight horror stories aside, I absolutely adored the country and everything about it. Now I try to visit whenever I can afford to do so (quite when I’ll be able to go again is anybody’s guess at the moment), and its impact on my dietary preferences, the decoration of my home and even my love life has been significant. As you might imagine, Sonatine is a film that is very dear to my heart.

Tokyo hard man Murakawa (Kitano) is becoming weary of his life as a yakuza enforcer and appears to have a long-standing beef with Takahashi (Yajima Ken’ichi), lieutenant to clan boss Katajima (Zushi Tonbo). When he is ordered by Katajima (via Takahashi, whom he subsequently beats up in a restaurant bathroom) to head to Okinawa to support the Nakamatsu clan in a war that has broken out with the Anan family, Mirakawa and his loyal lieutenants Ken (Terajima Susumu) and Katagiri (Ōsugi Ren) are uneasy about the prospect, having lost three men when they were sent to Hokkaido on a similar job and suspicious of Katajima’s true motives for this latest intervention. They and a group of new young recruits nonetheless travel to Okinawa, where they are met by perennially upbeat Nakamatsu lieutenant Uechi (Watanabe Tetsu), but soon after they enter their temporary office a bullet is fired through the window by an unseen member of the Anan clan. When subsequent tit-for-tat action climaxes in a barroom massacre, Murakawa, Uechi and their surviving soldiers go into hiding at a deserted and remotely located house on the Okinawa shoreline.

When I reviewed Lewis Teague’s film adaptation of Stephen King’s Cujo, I referenced a review that I’ve still not tracked down whose wily writer reasoned that any author could use a rabid dog to trap a woman and her child in her car, but only Stephen King would keep them imprisoned here for half of the book. With that in mind, I’d suggest that any filmmaker could send a group of warring gangsters to hide out at a quiet costal retreat, but precious few would have the balls to keep them there for much of the final two-thirds of the film. I’d venture that fewer still would have the skill and vision to make watching a group of violent men attempt to stave off boredom on an Okinawa beach for a solid half-hour of screen time such a spellbinding experience.

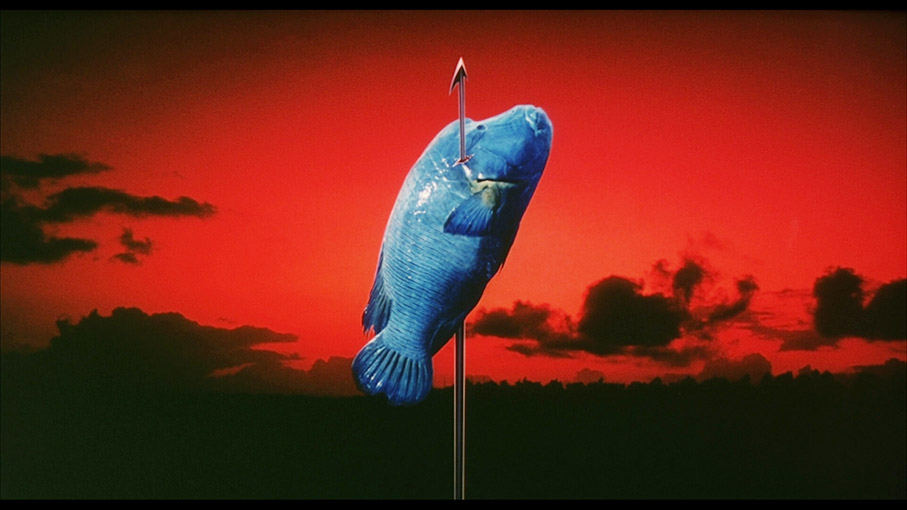

Sonatine breaks with convention even before its begins with a title that for most will have no meaning. It sounds Japanese but is in fact a reference to musical term 'sonatina' and, according to Kitano, how its form and structure relate to the personality and story arc of the main character and even his approach to how the film was made. I’m fairly certain I would never have worked that out myself. Then there’s the title sequence, which begins with the camera rotating and pulling back to reveal a bright blue Napoleon fish speared against a blood red sky, a striking but contextually mystifying image that shatters like a broken window to reveal the title, which is written in western romaji text rather than Japanese kanji. As it disappears, two letters at a time, we’re almost invited to find meaning in the order in which the vanish, or perhaps in the ones that remain. I’ve yet to come up with one.

The central character is introduced in similarly offbeat manner, with the film opening on a mid-shot of a lowly young mah-jong parlour worker as Murakawa and Ken pass by by him on screen left in shadow (watching the film again, I was surprised just often Kitano films himself in shade). The scene that follows is a more familiar one, with the owner of the parlour flatly refusing to pay the protection money being demanded by Murakawa, a defiance that we just know will backfire on him later. When it does, just before Murakawa’s trip to Okinawa, the results are predictably unpleasant, albeit in an unexpected way. Instead of being beaten or having his parlour trashed, the man is grabbed, transported to a quiet dockside spot and tied to a crane jib, then lowered into the water for the two minutes Murakawa reasons he can hold his breath. When he is pulled up he is gasping for breath and pleading for his life, but Murakawa responds by calmly wondering if he can last three minutes and has him lowered into the water again. He then gets into a conversation about the Okinawa trip with Katajima and seems to almost forget about the man. By the time he is pulled out the water again, he has drowned. “Looks like he’s dead,” observes Murakawa without a flicker of emotion, then shrugs it off with a casual “oh well” and leaves his minions to dispose of the body, which they instead leave dangling. For me, this is a key scene, for while the bathroom beating Uehara dishes out to Takashi demonstrates his brutality and lack of respect for the chain of command, it’s at the dock side that his casual callousness and scant regard for human life and suffering are confirmed. How, it seems to ask its audience here, can you possibly empathise with a man who could do such a thing? Of all the unpleasant scenes in Kitano’s cinema, this is the one that most upsets my partner, who though a hardened horror fan who didn’t flinch once during Miike Takashi’s gruelling Audition, always buries her face in a pillow during this sequence. Later, this emotional deadness will have echoes in Murakawa’s behaviour in Okinawa when he sees a man drag a girl named Miyuki (Kokumai Aya) onto the hideout beach and attempt to rape her, and instead of intervening he watches unemotionally for a while and then starts heading back towards the house. When the man confronts him and accuses him of being a pervert, Murakawa headbutts him to the ground, and when the man pulls a knife he is calmly dispatched by Murakawa’s gun, his body, once again, left for the lower rank gang members to dispose of.

Yet even before he heads to Okinawa we’re given tiny glimpses of the charismatic man that lurks beneath this coldly callous exterior, in the easy-going nature of the car conversation in which he chats with Ken about his desire to retire, and in the winningly naturalistic laugh he lets out after baiting the post-beating Takahashi with the question, “You’d be happy if I dropped dead, right?” and gets the reply, “Sure. I’d feel safe pissing again.” We’re also given an early taste of the blackly comic elements that will be woven into the drama when an argument between new young recruit Maeda (Morishita Yoshiyuki) and older hand Hirose (Kitajima Koichi) sees the young man stab his rival in the stomach, prompting every other recruit pile in and start beating seven bells of crap out of each other, while Murakawa, Katajima and the other yakuza sit emotionless and immobile and simply let it unfold. A short while later Maeda and Hirose are shown seated together on a minibus in Okinawa and Maeda asks Hirose if he wants something to drink, which prompts the older man to scowl at his attacker and note that his stomach is too painful, to which the unfazed Maeda responds with an understanding nod. This is one of a number of low-key double-act moments and relationships within the film – and Takeshi’s cinema in general – that subtly reference Kitano’s own background as one half of the manzai comedy act, The Two Beats.

Once the gang settles in to the Okinawa beach house, the film experiences an instantly seductive tonal shift, with impending boredom proving to be a transformative experience for these ruthless individuals, setting their collective inner child free and allowing these grown men to behave like the young boys they once were, but with the sort of toys that children would never have access to. This kicks off almost as soon as they arrive when Ken and Nakamatsu soldier Ryoji (Katsumura Masanobu) – another double act whose bond has organically evolved out of Ryoji’s constant questioning of the initially disinterested Ken – play William Tell games with beer cans by shooting them off of each other’s head with a real gun, then react like excited teenagers to the foolhardy risk of their own actions. Murakawa then ups the ante by using the same weapon to play Russian roulette with the two men, faking potentially lethal danger in a game that climaxes in a moment that will revisit him in a dream that proves to be a portent for later developments. This willingness to take risks that his slightly more level-headed subordinates shy away from resurfaces later during a visually striking night time firework battle, during which the laughing Murakawa gets so caught up in the game that he starts shooting at the opposing team with his pistol. Yet so effective is the location at stripping the men of their adult cares and responsibilities that even Murakawa ends up playing cheerfully childish games, digging carefully disguised holes in the sand and beckoning his comrades to join him and giggling uncrontrollably when they walk forward and fall in.

The epicentre of the transformation is what remains my favourite sequence in a film that really is brimming with extraordinary scenes, one in which reality drifts effortlessly and poetically into the realms of surrealistic fantasy. It begins with Murakawa, Ken and Ryoji building a toy sumo ring to stage bouts with tiny wrestlers cut from card, which are moved by vibrations generated by regularly tapping small handles on the side. It’s a short, but oddly captivating sequence that peaks when Murakawa’s diminutive model of famous wrestler Mainoumi falls over after just a couple of taps, prompting laughter that is simply too genuine to have been rehearsed. Leant a transitional continuity by Hisaishi Jō’s captivating, shamisen-driven score, the action then moves onto the beach and the marking of a full-sized sumo ring with seaweed, in which Ken and Ryoji act out the roles of rival wrestlers sternly preparing to do battle, their by-now cemented friendship symbolised by the complex and perfectly synchronised body-slap dance (which is sped up slightly for comic effect) they perform in preparation for an impending bout. When both men fall flat on the faces whilst attempting to rush Uechi, they are pulled to their feet and stand rigidly with their arms extended like human-sized dolls, and as the others rhythmically hit the sand they jitter around the ring in imitation of the cut-out wrestlers they were playing with earlier, as the camera cranes up in one of those movements that feels organically bonded to the action within frame. It’s an extraordinary sequence, one that dares to break with the film’s realist foundations and take us into the minds of its characters and see their gameplaying as their childhood selves might picture it. It’s in this sequence that we really see the lingering traces of the hierarchal barrier between Murakawa and his subordinates finally dissolve and this disparate band of gangsters evolve into a family, one that can laugh and play games together and can instinctively follow each other’s lead in whatever direction they may wish the gameplaying to go. This familial bond is cemented by what has become for me the most oddly affecting moment, when Murawaka and Katagiri are cheerfully watching the sumo silliness and are joined by an equally upbeat Miyuki, returning unexpectedly and seemingly none the worse for her night-time assault and its consequences. The way she just slots into this short short line of onlookers as if arriving late to a reserved spot, coupled with the smiling nod that she exchanges with Murawaka and the lingering look he gives her before returning his attention to the beach games, provides a tantalising glimpse of the potentially decent man that may well be lurking deep beneath this yakuza’s borderline sociopathic surface.

Given the nature of the events that lead the group to the beach in the first place, it seems inevitable that this near-idyll is not destined to last. Disruption eventually arrives in the form of a man who has been carefully cast to not look remotely like what filmic convention would lead you to expect – sorry if that seems confusing but I’m trying to avoid dropping major spoilers. His appearance shatters the recaptured bubble of innocence in which Murakawa and his comrades have come to enjoy living, triggering a final act in which the action expands beyond the confines of the beach and revisits the violence of the opening scenes. This peaks in and extraordinary confrontation in a hotel elevator, and a shootout whose convention-breaking handling was directly drawn on by director Rob Bowman for the opening scene of the William Gibson and Tom Maddox-penned X-Files episode, Kill Switch.

Sonatine is a sublime contradiction, a gangster movie that is also an anti-gangster movie, one less concerned with how yakuza hard men react to confrontation than how they might behave if they were temporarily stripped of purpose, amenities and contact with the outside world. It brings together all the experimentation of Kitano’s first three films and shapes it into an utterly beguiling and cinematically striking whole, with his skill for purely visual storytelling, coupled with his willingness to take chances, to strip a scene of music and dialogue for maximum effect and to usurp conventions making the film still feel fresh and inventive 27 years after it was first released. And there’s so much in the film that I’ve not even touched on that I’d love to prattle on about in unnecessary detail, but I’ve missed my self-imposed deadline and it might be nice to leave just a few things for newcomers to discover for themselves. In its effortless blending of humour with drama, in its character arcs, its visual storytelling, its use of sound effects, music and silence and its short, sharp and unexpected explosions of violence, this is absolutely the film that set the template for the Kitano films that followed. There’s a probably convincing argument to be made for why Hana-Bi is a richer and more complete Kitano Takeshi movie, or why Kids Return is a more personal and emotionally affecting one, but for all sorts of reasons, including the ones stated at the top of this review, Sonatine remains my personal favourite.

Just the news that Violent Cop, Boiling Point and especially Sonatine were coming to UK Blu-ray had me bouncing up and down on my chair in excitement. I’ve had a passion for these films for many years, but the previous DVD versions I’ve owned have left a lot to be desired. The Second Sight releases of Violent Cop and Boiling Point were both NTSC to PAL conversions and suffered from motion and sharpness issues as a result, and neither boasted particularly punchy visuals, though the second of those titles was a marginal improvement on the first. The Chinese ‘Collector’s Edition’ DVD of Sonatine that I imported, meanwhile, had the sweared-up American English subtitles (I’ll be getting to them), a non-anamorphic NTSC transfer and a picture so artificially sharpened that it made a visually striking film look genuinely ugly.

To say that the three 1080p transfers here are an improvement would be massively understating the difference between how the films look here and how they looked on previous DVD releases. All three transfers are of excellent quality, having a vastly improved level of picture detail over the DVDs (the clarity of the signs in long shots of streets leaves the fuzzier DVD equivalent in the dust) and better balanced contrast, with solid black levels that only occasionally feel a little strong in more dimly lit interiors, particularly when characters are dressed in black clothing. Daytime exteriors, particularly the sunlit beach scenes in Sonatine, look genuinely vibrant. There’s an earthy warmness to the colours for much of Violent Cop and some of the interiors in the other two films, but the palette becomes more consistently naturalistic with each film and peaks in the gorgeous-looking Sonatine exteriors, though individual sequences in both preceding films also shine, including a handful of nicely lit and photographed night scenes. All three transfers are framed 1.85:1 and all have been cleaned of any dust spots and wear and display the finest of film grains.

All three discs have Linear PCM 2.0 Japanese soundtracks, mono for Violent Cop and Boiling Point, stereo for Sonatine. All are clear, with clean rendition of dialogue, sound effects and music (though there is no music in Boiling Point) and no background wear or hiss to distract from Kitano’s signature use of silence.

New optional English subtitles appear to have been created for all three films. These have been Anglicised (at one point the word “wanker” is used as an insult) and do contain swearing that, while often in the spirit of the dialogue, is not an exact translation of the original Japanese. If I was not having to socially distance from my partner at the moment I could get into this in considerably more detail (my basic conversational Japanese is just not up to the task), but while there are a couple of times when the language feels unnecessarily spiced up to sound more aggressive than it is, in the case of Sonatine this is still a considerable improvement over the previous imported DVDs, where “fuck” was thrown around with tiresome abandon because, well, that’s how hardened criminals talk, isn’t it?

Audio Commentary on Violent Cop by Chris D

This is the first of two 2008 commentaries in this set by punk poet, singer, film historian and author of Outlaw Masters of Japanese Film, Chris D, whose woken-from-sleep delivery does not take away from the fact that he certainly knows his way round Kitano’s early cinema and he makes plenty of pertinent observations about Violent Cop, which he rates very highly. Topics covered include the main musical theme (which he admits his girlfriend helped him to identify), the elements that are common to cop movies worldwide, the blowhard characters who always come a cropper in early Kitano films, executive producer Kazuyoshi Okuyama, how violence is filmed and integrated into the story, the found locations and production design, the then rare inclusion of a gay villain in a Japanese film, and plenty more. He compares elements of Kitano’s films to those of Kurosawa Kiyoshi, notes some of the similarities between Kazuyoshi Violent Cop and the Dirty Harry movies (as well as how they differ), and even recalls seeing a real-life shoot-out and being struck by its similarity to the ones in early Kitano movies. I remember listening to this commentary when it first appeared on the UK DVD and not being a fan, but I definitely got more out of it this time around.

That Man is Dangerous: The Birth of Takeshi Kitano (20:20)

Associate producer Mori Masayuki and actor Ashikawa Makoto (who plays rookie cop Kikukchi) are interviewed about their experience of making the film, and given that none of the writing on the film that I’ve read has been from the perspective of those involved in its production, this is a really welcome inclusion. Ashikawa recalls how he first met Kitano at an amateur baseball game, how the script was effectively set aside and improvisation encouraged, how this first-time director initially made light of the filmmaking process and ultimately won over the hearts of the more serious-minded crew, and more. Mori remembers being convinced from the start that Kitano could make a film like this and that he kept the characters and settings of the script but rewrote 90% of it, which prompted original writer Nosawa Hisashi to ask for his name to be taken off the credits. He also provides the most detailed explanation I’ve yet come across of why original director Fukasaku Kinji left the project and why the directorially inexperienced Kitano was offered the job in his place. Mori also quotes Kitano as saying of his role as an artist, “Nobody can catch me, I won’t let anyone take hold of me.” Interestingly, the subtitles on some of the clips here differ in small but telling ways from those on the main feature.

Violent Cop Trailer (2:10)

A solid enough trailer that pushes the film’s crime movie credentials but has enough spoilers to be avoided until after watching the film itself.

Commentary on Boiling Point by David Jenkins

This second commentary is by film critic and Little White Lies editor David Jenkins, whose soft-spoken enthusiasm I found instantly engaging. Like Chris D, he’s an unabashed enthusiast for Kitano’s cinema and believes that Boiling Point (whose title he usefully explains, though he appears to have missed the in-film score reference) is “one of the director’s most robust and playful offerings” whilst freely admitting that he wasn’t so enamoured with it when he first saw it. He highlights a number of elements that mark this as a Kitano film, talks about the creation of comic moments through editing, highlights what he believes is the director’s funniest ever scene, and points out that in this film you never really know where the narrative is heading next. There’s an interesting story about his first experience of Kitano’s cinema via Hana-Bi, a shout out to the efforts of Asian cinema expert Tony Ryans for his championing Kitano’s early films and helping to get them shown in the west, and he ends up encouraging you to watch the film again, regardless of how many times you have seen it, to pick up on the number of recurring or mirrored motifs within. There’s plenty more, all of it enthralling. I really enjoyed this – informative though Chris D’s commentaries are, I found myself itching to hear what Jenkins might have to say about the other two films in this set.

Okinawa Days: Kitano’s Second Debut (20:10)

Shot in the same style and by the same people as the That Man is Dangerous, this featurette is constructed from interviews with Mori Masayuki – who received a full producer credit on Boiling Point – and actor Yanagi Yurei, who played the young Masaki. Yanagi’s story of how he was promoted from a “good for nothing” apprentice member of Takeshi’s Army to lead role in a film is an intriguing one, and he acknowledges that it launched his subsequent acting career. He also interestingly dissects Kitano’s signature before/after approach to visual gags, explaining that in Kitano’s view a joke should consist of a setup and a punchline and that there should be as little as possible between the two. Mori reveals that when he first saw the dailies from the shoot he instantly understood Kitano’s vision and believed that he was seeing the birth of a new director and new type of visual storytelling, and he does a lovely job of describing the film as a diamond in the rough and how it contains many pointers to later Kitano films.

Boiling Point Teaser Trailer (1:03)

One of the most peculiar teasers I’ve seen for some time, which begins with a montage of details from Hieronymus Bosch paintings set to an note-altered adaptation of Tubular Bells, which then cuts to a single shot from the film of Uehara, Masaki and Kazuo sitting on the back seat of a moving car, while a narrator simply repeats the Japanese title five times in a row, during which it appears graphically over a screen of TV static. I doubt anyone watching this had a clue what they were in for, but it does intrigue.

Boiling Point Trailer (2:03)

The same trailer, but with more shots from the film, some peculiar title cards (“Virus infiltration,” “Your encephalons are in danger,” “Demolishing your frontal lobe”), some eye-catching wipes a handful of spoilers. The title gets repeated five times again, just in case you missed it.

Audio Commentary on Sonatine by Chris D

The second Chris D commentary in this set is every bit as knowledgeable of its subject as the one on Violent Cop. There are some nice observations about the first third of the film, one of which I’d somehow not picked up even after several viewings and that I instantly felt inattentive for missing. He neatly captures a key aspect of Kitano’s crime dramas by suggesting that the director is an expert at subverting stereotypical plot elements whilst keeping them real, and that he creates humour out of the conflict between what we expect to happen and what actually transpires. He talks briefly about some of the actors, cinematographer Yanagijima Katsumi and composer Hisaishi Jō, though I found myself taking issue with his belief that some of Hisaishi’s music here is somehow “too self-conscious.” Sorry? Then again, by this point we’d already fallen out a bit due to his opinion that my favourite sequence in the film is the only one that doesn’t really work, then setting me on edge just a tad by describing it as “pretentious,” which for too long has been the go-to term for professional and non-professional commentators alike when they want to criticise a film or an element of it and cast it as a fault of the filmmaker rather than the personal opinion it always is. I should say I absolutely get where D is coming from here, I just completely disagree with him on it. Whatever your view, this is still a worthwhile listen, and I’m completely on board with D’s claim that Kitano is an intuitive filmmaker who always knows exactly where to place his camera.

Sonatine Trailer (0:51)

A fast-cut trip through some of the more violent moments, which pauses briefly to focus on the iconic shot of Kitano holding a gun to his head from the beach game Russian roulette sequence (see the above screen grab).

Booklet

Right up there with the standard-setting booklets from the likes of Indicator and Arrow, this one opens with an excellent and detailed essay on Kitano’s career by critic, filmmaker and Midnight Eye co-founder Jasper Sharp (the very person I’ve quoted at the top of this review, though from a different source), one that would make for a perfect introduction for those not familiar with the man and his work. Next is a similarly thorough and knowledgeable piece on Violent Cop and its production by Tom Mes, the author and co-author of numerous books on Japanese cinema and a regular provider of audio commentaries on discs of the same. Up to bat next is Mark Schilling, the senior film reviewer for The Japan Times, who takes a perceptive, almost scene-by-scene look at Boiling Point and even offers up a slightly different interpretation of the Japanese title to the one most commonly seen – he suggests that October here was a reference to the film’s originally planned month of release, and that it was rendered meaningless when it was came out in September instead. Then again, wouldn’t it be rendered meaningless anyway in the years to come, when few would even be aware of exactly when it was first shown? Just throwing that in. Jasper Sharp is back for a look at Sonatine and some the contemporary critical responses to it, including one by the Mark Schilling, another critic who thought the film was ‘pretentious’, something Sharp regards as surprising in hindsight. This is followed by an excellent 1993 Time Out review of Sonatine by Geoff Andrew, one in which he smartly dismisses the notion that the film could be seen as heavy-handed or pretentious. Good on you, sir. Finally we have a useful appreciation of ‘Beat’ Takeshi by Japan-based film writer James-Masaki Ryan. Full credits for each of the films – and that means more thorough than the ones you’ll find on IMDb – and even the special features have also been included.

It’s no exaggeration to say this is a dream release for me, one that finally gives three of my favourite films by one of my favourite modern filmmakers the sort of upgrade they have been aching for since I first clapped eyes on them through the BBC and Film 4 TV screenings many years ago. With the rest of Kitano’s early features already available on Third Window Blu-ray, this BFI release effectively completes the set. The transfers are first-rate, the extras solid and the booklet is excellent. This is everything I hoped it would be. Highly recommended.

|