| |

"And the dog seemed to know. His terrible, thoughtless eyes never left Donna Trenton’s wide blue ones. He paced forward slowly, almost languidly. Now he was standing on the barnboards at the mouth of the garage. Now he was on the crushed gravel twenty-five feet away. He never stopped growling. It was a low, purring sound, soothing in its menace. Foam dropped from Cujo's snout. And she couldn’t move, not at all." |

| |

Stephen King – Cujo |

I'm not a dog person. Then again, I'm not a cat person either. In fact, I'm not an any-animal-you-care-to-think-of person. But for some reason I do have a particularly chequered history with dogs. Back when I was a child, every time I cycled in the direction of the nearest town I would be chased by one of those aggressive yappy canines that only just qualify to be called dogs at all and that was mysteriously allowed to run free on the main road by its invisible owner. If I headed in the other direction, the dirt road I was forced to navigate would often be blocked by a snarling Alsatian. The only dog my family ever owned as a pet had a fit and inexplicably died, and during the course of a single summer when I worked part-time at a local dog kennels, the one time I was bitten was by the establishment's own Alsatian just seconds after being assured that its bark was worse than its bite. I thus find it easy to accept the notion of demonic dogs in literature and film, especially as the canines in question tend to be the sort of breeds that could rip you to shreds even if not possessed. This makes perfect sense, of course, as if you want to terrify an audience you call on the Hound of the Baskervilles, not Foo-Foo the poodle.

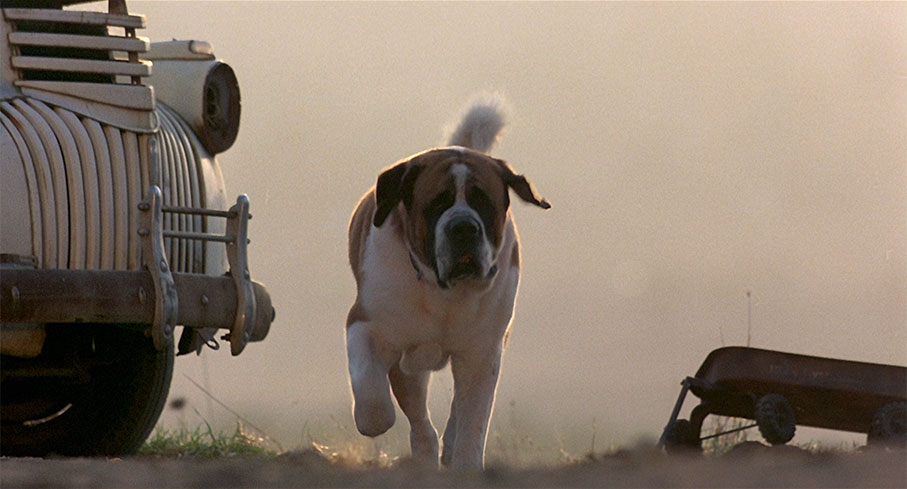

Stephen King, of course, rarely takes the obvious route. In his 1981 novel Cujo, the monstrous dog was not a Doberman or Rottweiler but a St. Bernard, an immensely likeable animal whose public image is one of helpful benevolence and that is known primarily for plodding through Alpine snow in search of lost hikers with a keg of revitalising brandy tied to its collar. So positive is the image of the St. Bernard, indeed, that having such an animal turn on humankind feels almost like a betrayal. And St. Bernard dogs are big. If a rabid St. Bernard came running at you then good luck trying to flick it aside with your foot.

In King's book and the 1983 film adaptation under review here, Cujo is initially the friendly dog of legend, the family pet of farm-dwelling Joe and Charity Camber and their young son Brett. As the film opens, Cujo is playfully chasing a rabbit that escapes by running into a small underground cave, one whose entrance is so narrow that only the dog's head is able to squeeze through. Here, his loud barking prompts several bats to fly over and bite him on the nose. Following this, we're introduced to the Trenton family. Husband Vic is a successful advertising executive whose most successful creation is the Sharp Cereal professor ("Nope, nothing wrong here!"), his wife Donna is having an affair with buff local handyman and family friend Steve Kemp, and their young son Tad is convinced that there are monsters in his closet despite his parents' assurance that monsters do not really exist. You don't have to be a fan of Stephen King's work to see where this is going. The two families connect when Vic is looking to get a fault on his car checked and is tipped off that Joe Chamber is the man to talk to. Later, when Vic is out of town on business, Donna's older and more fault-ridden car really starts to play up, so she trundles out to the Cambers' isolated farmhouse with Tad in tow, unaware that the property is now empty and that the bat bite has transformed the previously friendly Cujo into a rabid killer.

One thing that struck me immediately on revisiting the film so many years after I last saw it was how tightly economical its storytelling is. As Lee Gambin concludes in his commentary on this very disc, it's a fat-free film that boasts a cinematic and even performance economy that is rare for horror in any decade, let alone the traditionally loud and flamboyant 1980s. This is clearly evident from the opening scenes. That the infected Cujo is becoming intolerant to loud noises is communicated solely through a closeup of his face as Joe works a metal grinder or empty beer cans clatter around him (full marks to the sound design team here). Similarly, that Donna is having a sexual relationship with Steve that she is starting to have second thoughts about is initially indicated through her body language, but made clear when she gets up from a bed in which Steve is lying and walks out of his field of view to put on her underwear (it's worth noting that on the UK VHS release, the two were engaged in a nudity-free sexual encounter that is not present in this theatrical version). The film then cuts to a shot of the Trenton family at dinner that is framed through a window that places physical barriers between Donna, Vic and Tad, a visual illustration of the divisions that are opening up in this imperfect American family that works so well because it's not hammered home (the camera dollies in to uncertainly unite the trio just seconds later). It's the same story after Vic spots Donna arguing with Steve in the street and comes home to find Steve at the house and Donna on the floor clearing up a mess caused by further conflict between the two. "Yes or no?" he asks her, to which she replies, after a guilty pause, "Yes." That really is all that's needed.

By the time Cujo hit UK cinemas I was already a bit of a fan of director Lewis Teague thanks to his excellent second feature for Roger Corman, The Lady in Red, and his terrific 1980 monster movie, Alligator, both of which were scripted by John Sayles, who at this point in his career was the most consistently inventive genre scriptwriter working in American cinema. In collaboration with editor Neil Travis and cinematographer Jan de Bont – who 11 years later would made an impactful move into the director's chair with Speed – Teague repeatedly demonstrates how to tell a story cinematically rather than through expositional dialogue. This is strikingly demonstrated when we first encounter Tad, whose fear that there are monsters in his closet is communicated solely through the cinematography, the editing, a superb use of a subtly oversized set and the performance of talented 6-year-old first-timer Danny Pintauro. Indeed, we're almost six minutes into the film before the first word is said, by when we're well aware of Tad's terror of the artificial monsters that lurk in his dark, and that there is a very real one in the making over at the Camber farm.

Given the sheer amount of character detail in King's original novel, screenwriters Lauren Currier and Don Carlos Dunaway have done a fine job of paring it down to the essentials without losing the essence of the main characters as written. There's a good deal going on beneath the surface here, particularly in the opposing notions of imagined terrors and real-world threats, and there is a subtle commentary at work on the dysfunctional nature of the modern American family. Unhappy mothers are a particular focus here, with an emotionally unfulfilled Donna copping off with the local stud and Charity Camber seizing a chance opportunity to flee from her abusive husband – tellingly, both women end up looking after their young sons far away from their respectively self-absorbed fathers.

All of the story threads neatly pull together to get Donna and Tad to the Camber farm and trapped in a vehicle that we know is going nowhere, where they will come under siege from a large and menacing animal with no hope of immediate rescue (ah, for the days when you didn't have to somehow disable your mobile phone to isolate your characters). Here is where the film really earns its thriller credentials. I wish I could remember which reviewer wrote of the film on its release (and I've searched my archives to no avail) that any writer could have a mother and her child trapped in an immobile car by a rabid dog, but only Stephen King would think of keeping them there for half of the book, a decision the film wisely takes its cue from. Given the essential simplicity of the setup and the very real danger of trying the patience of the audience, it's a risky strategy. But it works, and how.

By virtue of its size and strength alone, this dog poses a most convincing threat, and being rabid there's no reasoning with it, no chance that Donna might be able to calm it down or somehow make tentative friends with it over time. Like the occupants of Quint's fishing boat in the latter stage of Jaws, Donna and Tad are essentially prisoners in a fragile vehicle that is under assault from a creature that cannot be easily confronted and whose attacks start to take on the air of a personal grudge. This is more pronounced in King's novel, which has a supernatural aspect that has largely been abandoned here, though this is still creepily suggested when the worn-down Donna wakes in the night and turns to see Cujo silently watching her through the side window of the car, as if carefully contemplating his next move against her. If this weren't enough, the blazing summer heat transforms the car into an oven, forcing Donna to keep windows precariously open and starting Tad on the road to potentially dangerous dehydration, which itself pushes Donna towards a decision that could have lethal consequences for her son either way.

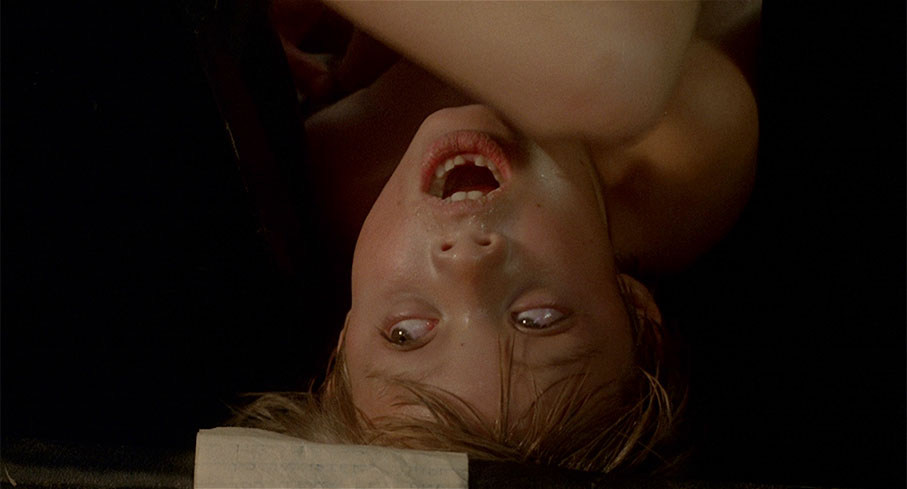

Teague milks this situation for all it is worth, his camera prowling up to an open car door to startlingly misdirect us, and later revealing Cujo's close proximity to the vehicle as Donna becomes convinced that he is in hiding. At one point the camera pulls back from the car to emphasise Donna and Tad's isolation, only to then crane down to the reveal watching Cujo and move slowly round and into a close-up the dog's eyes – a little fourth wall-breaking this observation may be, but the sheer fact that the animal completely ignores a camera that is almost in its face and remains steadily focussed on Donna and Tad gave me one of my biggest shudders in the film. A decision to combine the use of trained dogs, a mechanical dog's head and a stunt man in a dog costume sounds on paper like recipe for an unconvincing monster, but so skilfully are the three elements matched in the editing that I defy anyone to spot which shots contain the actual animals and which do not. The tension is maintained by only occasionally cutting away from Donna and Tad's plight – usually to confirm that no-one will be coming to their aid any time soon – and a sequence where Donna steps out of the car unaware that Cujo is just a few feet away had me jumping up and down in my seat in fear, and I'd seen the movie a couple of times before. This builds to a terrifying in-car assault on Donna and an extraordinary 360 degree circular pan inside the car that expressionistically captures the fear, despair and hysteria of its occupants. This rotation increases to a dizzying speed, then transforms into the tail end of a nightmare that wakes Vic in his far away hotel room, stirring in him an instinctive fear that he may by this point be too late to act upon.

Performances really matter here, and Dee Wallace hits an absolute career best as Donna, quietly expressing her discomfort and guilt at her affair in the smallest of gestures in the first half, then utterly convincing in her terror, desperation and maternal fury in the second. She's given a real run for her money the young Danny Pintauro as Tad, whose wide-eyed panic and tears of despair are so convincing that I was relieved to hear the actor talk in the special features about what a great time he had making the film, as I'd otherwise be convinced he had been traumatised by the experience. They're backed by a consistently strong supporting cast, with solid performances from Daniel Hugh Kelly as Vic, Christopher Stone as Steve, the ever-reliable Ed Lauter as Joe Camber and Kaiulani Lee as his put-upon wife Charity. A special mention should also go to the dogs playing Cujo, who may be responding to training and faking their fury through play, but utterly convince as a large rabid canine killing machine.

The one element I can't really discuss but would like to is the ending, which differs dramatically from the book in one crucial way, something I may discuss in more detail in a later blog, though be warned that doing so will involve dishing out major spoilers. Either way, Cujo remains to this day one of the strongest film adaptations of a Stephen King horror novel, compressing the book's narrative into a tight, tense and impressively layered 93 minutes whose subtextual detail needs at least two viewings to fully appreciate. It's a terrific example of physical, pre-CG creature horror, and an object lesson in how to tell a story cinematically and with real narrative economy.

I couldn't find any details in the booklet or the press release about who carried out the restoration that was the source of the 1080p 1.85:1 transfer on this Blu-ray, but whoever it was they did a bang-up job. The colours are rich without feeling over-saturated and the contrast is very nicely balanced, with solid blacks, very good shadow detail and no burn-outs on highlights. Detail is crisp, and while some shots have a slightly softer feel, it seems clear that this was the result of filtering during the shoot, as the softness in question has the distinctive look of a light fog filter (yes, I've used them). As expected, the image is consistently clean, and a fine film grain is visible throughout.

There are two soundtrack options available, the original mono as Linear PCM 2.0 and a DTS-HD Master Audio 5.1 surround track. Sonically, there's not a huge difference between them, as both have clear reproduction of dialogue, music and effects and both boast a decent dynamic range, but there's a little more finesse to the 5.1 and some distinct separation both of sound effects and especially music, which also makes use of the rear speakers.

Optional English subtitles for the deaf and hearing impaired have been included for the main feature.

I know I've been a little whiny in the past when it comes to Lee Gambin's habit of repeatedly saying "I love this…" on a couple of his previous commentary tracks (it's a personal gripe that I've also had with a number of filmmakers when commenting on their own perhaps too recently completed movies), but there's no doubting that he knows his stuff, and when it comes to this release he really is the hero of hour, being the driving force behind almost every one of the many special features here. Cujo is one of his favourite films, one he has extensively researched for his detailed book, Nope, Nothing Wrong Here: The Making of Cujo. As well as providing a commentary track, Gambin is also the credited director of every one of the included interviews and is the host of the feature-length Q&A with Dee Wallace on the second disc. Sir, we salute you.

Lee Gambin commentary

Yes, there are a few "I love this" moments here, but I'm discarding any complaints I may have previously made on this score due to the almost dizzying amount of information Gambin provides on the film and its making. Some of it is repeated elsewhere in the special features, but there's plenty that is specific to this commentary, particularly Gambin's fascinating examination of the layers of subtext that run throughout the film, none of which feels fanciful and that collectively add to your appreciation of just what the filmmakers achieved here. Several times he references King's novel, of which he is also an enthusiastic fan, makes a solid case for why the ending works as it is, and he also highlights the work of all the key contributors on both sides of the camera. There's so much more here, all of it worth hearing. An essential extra.

Dog Days: The Making of Cujo (42:48)

Written, produced and directed by Laurent Bouzereau in 2007 for Lions Gate Films, this three-part documentary on the making of Cujo is built around interviews with a number of the key players, including director Lewis Teague, producers Daniel H. Blatt and Robert Singer, actors Dee Wallace and Daniel Pintauro, cinematographer Jan de Bont, editor Neil Travis and composer Charles Bernstein. The making of the film is told in chronological order, with each step covered in enthralling detail, albeit with one rather interesting omission – that another director was hired and eventually fired before Teague was brought on board does get a mention, but Peter Medak (for it was he) is never identified by name. A lot of the content is covered in greater detail in the interviews elsewhere on this disc, but this still makes for a most comprehensive introduction to the film's making and there is content here that does not appear elsewhere, including how that extraordinary 360 degree in-car rotating shot was achieved.

Dee Wallace Interview (41:34)

A lively and substantial interview with lead actor Dee Wallace, who recalls working with director Lewis Teague, reveals a specific issue she had with original director Peter Medak's approach, sings the praises of young first-timer Daniel Pintaro, and talks about the pressure to be on top form all of the time due to the unpredictability of the canine performer, getting completely immersed in the role, and much more. She discusses working with her then husband Christopher Stone and amusingly suggests that doing a sex scene with your real-life partner is akin to having your mother standing at the end of the bed. She also reveals that the toughest aspect of the shoot was making it looking like they were sweltering in summer heat when the film was shot in freezing mid-winter. She also states categorically that she is immensely proud of her work on the film, which I can't see anyone having a problem with.

Charles Bernstein Interview (35:37)

Composer Charles Bernstein gets into some interesting specifics about the writing of the score for Cujo and talks about his influence on the title animation, the concept of giving characters their own themes, his long-term working relationship with Lewis Teague, scoring for monsters and villains in horror movies, and more.

Gary Morgan Interview (26:10)

Effervescently cheerful stuntman Gary Morgan recalls landing the job on Cujo, working with Lewis Teague and Dee Wallace, wearing (and sometimes having fun with) the dog suit, the main stunts for the film, learning animal movements from watching the real dogs, and more.

Jean Coulter Interview (21:09)

Stuntwoman Jean Coulter – who doubled for Dee Wallace during the more intense dog attack shots – reveals how she first got into stunt work and recalls forming a relationship with the dogs, working with Lewis Teague, Dee Wallace and dog trainer Karl Lewis Miller, and plenty more. It's here we get the full harrowing story of the stunt that saw the St. Bernard she was play-wrestling with become agitated and bite off her nose (I am not exaggerating here), which was only able to be re-attached because it was still hanging on by a thread of skin and so still had a blood supply. What's extraordinary is how philosophical she remains about the risks of her trade, and like others interviewed here she thought the finished film was terrific.

Marcia Ross Interview (20:03)

Casting director Marcia Ross remembers working with Peter Medak on the casting – which was completed by the time Medak was replaced by Lewis Teague – and has strong memories of selecting and auditioning specific actors.

Kathie Lawrence Interview (13:55)

Special effects artist Kathie Clarke Lawrence shares her recollections of working with the dogs and animal trainer Karl Lewis Miller, creating a dog costume for stunt man Gary Morgan and another for a Labrador that was brought in to do stunts that the St. Bernard dogs might refuse to do, a backup plan that from what I can gather was never used. She also talks about the process of designing and creating the fake dogs and her first steps into this specialised area of the film industry.

Robert Clark Interview (12:5)

Visual effects artist Robert Clark covers similar ground to his wife and working partner Kathie Clark Lawrence, including working with dog trainer Karl Lewis Miller and the construction and operation of the dogs. Intriguingly, he has a different take to stuntman Gary Morgan on how the sequence where Cujo rams his head into the car was done. I'm staying out of this one.

Teresa Miller Interview (28:14)

The daughter of Karl Lewis Miller, who followed in her father's footsteps as an animal trainer for movies and sometimes worked alongside him, recalls her father's work on the film and sharing their house with the St. Bernard dogs that played Cujo, each of which was adept at specific actions. One thing that comes across in the special features is that nobody can agree on just how many dogs were actually employed, but Miller claims four and since she lived with them during the course of the shoot, my money's on her count as the accurate one, a point on which Lee Gambin appears to agree. To this day she regards Cujo as her father's finest achievement, and fondly recalls Stephen King personally thanking him for his work on the film when she was working with him on the King adaptation, Cat's Eye.

Original Trailer (1:49)

A very 80s sell with a deep-voiced narration that avoids showing too much of the dog but has lots of shots of people looking at it in terror. Sourced from an SD 4:3 original.

TV Spot #1 (0:30)

No sign of the dog at all in this similarly toned TV spot.

TV Spot #2 (1:29)

An expanded version of the above, with lots of alarmed faces but not a single shot of the title creature.

Dee Wallace Q&A (100:53)

Recorded at the Cinemaniacs & Monster Fest in Australia in 2015, this Q&A with actor Dee Wallace is conducted by Lee Gambin, which finally allowed me to put a face to a voice that I've become very familiar with over the past couple of years. As you can see from the running time, this is a long interview, one that is only occasionally interrupted by screened clips from films under discussion that due to copyright restrictions have not been included here. Some of what's covered, notably stories about the making of Cujo, are repeated elsewhere, but much of it hasn't and Wallace herself is so entertaining a raconteur that the 101 minutes really do just fly by. Fed effectively by Gambin, Wallace takes us through the key early films of her career and has several stories about the making of each, which are always informative and often very entertaining. We learn how she landed a role in The Stepford Wives through a chance meeting with director Bryan Forbes, how tough the shoot was on Wes Craven's seminal The Hills Have Eyes, and how she reacted to her then fiancé Christopher Stone having to do a sex scene with Elizabeth Brooks on Joe Dante's The Howling. She recalls her agent's astonishment that she wanted to read the script before accepting the key role as the mother in E.T. ("It's a fucking Steven Spielberg movie!") and emotionally recounts the illness she suffered when shooting The Frighteners and how kind director Peter Jackson was to her. Most amusingly, she knowingly says of the title creatures from Critters, "They were these big, hairy balls…" There's so much more here, and though we are restricted to a single imperfect camera angle, so-so image quality and sound recorded on an on-camera microphone (which at one point the operator appears to noisily juggle with), the content alone makes this worth tolerating. Gambin is also really on form here, notably when he talks about The Hills Have Eyes and says to the audience, "It's a masterpiece. If you haven't seen it… umm… there's something wrong with you."

Kim Newman on Cujo (27:03)

Just when you think there can't be anything else to add to what's already been said, you can rely on Kim Newman to bring something new to the table. Instead of focussing specifically on Cujo, Newman instead provides a comprehensive look at Stephen King's rise to prominence as the premiere genre writer of the 1970s and 80s and a number of key film and TV adaptations of his work. When he does talk about Cujo, he does so from a different perspective to those who were involved in its making and has his own very personal take on the film's ending in relation the a key change it made to the book. As ever with Mr. Newman, a very worthwhile inclusion.

Booklet

This impressive 60-page booklet kicks off with a most perceptive essay by Craig Ian Mann titled, Don't Blame the Dog: Cujo vs the Nuclear Family, which looks at the film's portrait of the American family unit in freefall and the socio-political situation in which King's early novels were written and the film adaptations of them were made. Next up, we have a piece titled The Beast Within: Stephen King's Cujo and the Nature of Evil in which scriptwriter, novelist and film essayist Scott Harrison looks at the writing of one of Stephen King's darkest novels and the production and release of this film version. There's a sizeable extract from Lee Gambin's book about the making of the film, Nope, Nothing Wrong Here: The Making of Cujo, which should help to sell a few copies to those who've yet to read it and includes several quotes from those involved in the film's making. Also included are a selection of production stills, reproductions of posters and the main credits for the film.

It's rare and lovely thing when I revisit a film from my younger days and discover that it's even better than I remember, and this was definitely the case with Cujo, a film whose cinematic economy and narrative layering should see it used as a teaching tool at film schools, while the very real physical threat created by the use of real animals fills me with a nostalgia for pre-CG horror cinema. A splendid film gets an excellent transfer and a collection of special features so plentiful and content-rich that they'll keep you busy for a week (they did me). A superb release from Eureka that gets our highest recommendation.

|