This is a belated follow-up to my review of the Eureka Blu-ray release of Cujo, in which I stated that I had some small issues with the film's final scenes and the way that it ends, and intimated that I might go into more detail in a subsequent blog, which was delayed by…well… you know the score by now. I'll state up front that it includes spoilers for the end of the film and its source novel, and if you've not seen or read either and don't wish to know how either conclude, then don't read this. Seriously. There are also spoilers for the endings of The Last Holiday, A History of Violence, The Blair Witch Project and – to a degree – The Parallax View, but these are signposted in advance (well, the last one isn't, but I avoid getting too specific with that one). You have been warned.

Not so long ago, a friend asked me to break down how I approach the process of writing a film or disc review, and one of the things that came out of the discussion is that even once you know how you're going to get started and hit your flow, it can be tough to know how to tidily conclude it. Filmmakers face a similar challenge, but in their case the problem is amplified by the fact that the ending of their movie is going to be fresh in the mind of any audience member when they walk out of the cinema. If a film starts badly then picks up and ends well, few will leave with negative memories of it, but if it starts with a bang but ends badly then you can bet that a sizeable portion of the audience will hit the streets wearing the facial expressions of people who've just eaten particularly sour lemons.

The 1970s is quite possibly my favourite era for American film, in no small part because I saw so many of the works we now regard as classics of the period on the big screen in establishments I frequented several times a week during my film school years. But while the decade gave us some of the most memorable of film endings – think The Parallax View, The Godfather, One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest, etc. – there were also a few too many that didn't so much conclude as just come to a stop, often cutting to a wide or an aerial shot of the location to signal to the audience that the credits were about to roll. Horror, of course, had a different issue. After Carrie launched audiences out of their seats with its belter of final twist shock ending, a few too many genre movies followed suit and insisted on topping their conclusion with a final twist, revealing that the monster wasn't dead after all, or had a mate, or had given birth to a baby monster, or if the monster was human that it had passed on its murderous traits to a protégé. It all became a bit predictable and really bottomed-out with the found footage subgenre, which followed the template set by The Blair Witch Project so slavishly that almost all of them had exactly the same bloody ending (spoiler warning), one where everyone dies, including whoever it is holding the camcorder on which the whole thing was supposedly shot, a device that would then be dropped to the floor to catch the film's ‘haunting' final image. So ubiquitous did this final non-twist become that the makers of even the best and most inventive found footage horrors seemed to feel obliged to end their films in this manner. Nowadays, mega-budgeted, star-driven Hollywood films are every bit as predictable in their own sweet way, with a certainty that the (sometimes reluctant) hero will defeat the villain and be happier and wiser for the experience by the end than he was at the beginning – check out just how many action-driven American films are really about the building or reunification of the family unit. We know now that the hero will triumph even before we buy our ticket for the film, not just because big stars don't die in tentpole movies, but because so many of these them are made with an eye on a possible sequel or franchise.

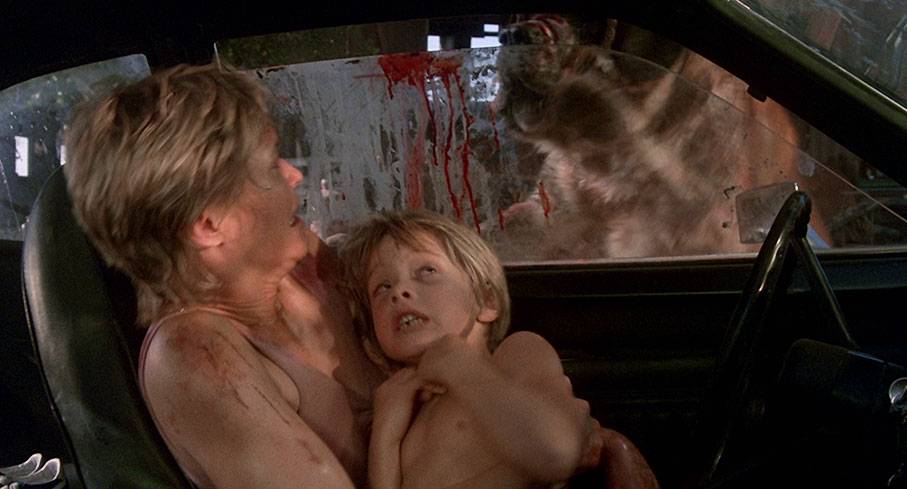

A couple of months back, I reviewed Eureka's superb Blu-ray release of Cujo, a tense, smart and tightly constructed adaptation of what remains one of Stephen King's darkest novels, a book he later claims he barely remembers writing because he spent the period in a cocaine-induced haze. Would that I could write a fraction as well as he did while bombed out of my head. Or sober, for that matter. I'm going to assume that most of you know the premise of the film and book or you wouldn't be reading this, but here are the basics. When the engine of their car dies at an isolated farmhouse, unhappy housewife Donna and her young son Tad are attacked by a rabid St. Bernard dog. With no-one aware of their location they are kept trapped in their car for three days in sweltering heat, during which time Donna is bitten by the dog and Tad starts to suffer from dehydration and heat stroke.

The book, as we had by then come to expect from King, was an utterly gripping and sometimes terrifying read, but it delivered its biggest gut-punch towards the end when the desperate and furious Donna confronts the dog and beats it to death, only to discover that that Tad has died anyway, a shock revelation that is followed by an emotionally affecting coda involving Donna, her husband Vic, and the dog's former owners. The film, which in many ways is impressively faithful to the novel, makes a couple of significant changes to this last part of the story. Here Donna kills the dog and carries the unconscious Tad into the farmhouse and is able to revive him, a change to the novel that was made by the filmmakers after careful consideration and consulting with Stephen King himself, who admitted that if he was writing the novel today then he wouldn't have let Tad die. The reasoning here was that what worked in the book – the emotional wallop it delivers is considerable – would not work so well for the film, whose audience, it was reasoned, would be more likely to feel cheated by a twist that robbed them of an ending that the movie had led them to expect and emotionally work for. Quite why novels are able to take readers to places that a film is more reluctant to visit is probably a subject for a different essay. The end-of-book coda is dispensed with completely in the film.

The thing is, I do understand this decision. I'll admit that I'm a bit of a fan of downbeat endings, but there are times when my emotional investment in a character and their survival is so great that any move to trip them up at the last hurdle does indeed feel like a cheat. If you want an example, try the 1950 Last Holiday (major spoiler ahead), in which Alec Guinness plays lonely and luckless George Bird, a man who is informed by his doctor that he has only a few weeks to live and advised to spend his final days on a holiday at a plush resort. Here, for the first time in his life everything goes right for him, and were he not doomed to die, opportunities aplenty would be opened up for his future. Then, in a wonderfully uplifting twist, he meets a specialist at the resort who assures him that he does not have the disease with which he has been diagnosed and, in a scene that had me bouncing in my seat with glee, he returns to confront the doctor who mixed up his x-rays with those of a genuinely terminally ill patient. Then, just as he heads back to the hotel to enjoy the life he spent the last few weeks convinced was going to be cruelly denied him, he's fatally injured in a car crash and dies. Man, was I pissed off by what felt to me like cruel and unnecessary final twist, one that had none of the sociopolitical subtext of the shock ending of a political thriller like The Parallax View and felt as if it was written (by J.B. Priestley, no less) for no other reason than to catch the audience out and kick it in the nuts.

How I would have responded to Cujo had it retained the novel's ending is impossible for me to even speculate on as I was already a fan of the book when I first saw it so was expecting events to take a dark turn and thus did a bit of a double-take when Tad unexpectedly sputtered back to life. But as I said, I do understand the decision to keep him alive and am not going to claim it works against the film. No, it's what follows – some of which relates directly to that alteration – that I still have a couple of issues with. The first thing that bugged me comes immediately after Tad's resurrection, when the previously thought dead Cujo unexpectedly jumps in through the kitchen window and is shot dead by Donna, a twist that was not in the novel and that is clearly only there because of the aforementioned post-Carrie tradition of bringing the monster back from the dead for one last shock. Indeed, in his interview on Eureka's Blu-ray, director Lewis Teague all but admitted that the decision to include this sequence was made primarily because the audience of the day expected it to be there. It's a horror movie, the monster is dead, where's its surprise last appearance? In a film this tightly and purposefully constructed, this is the only moment that to me felt utterly superfluous, and a film whose direction, performances and extraordinary practical effects had utterly convinced me of the reality of Donna and Tad's plight, this is the one point where realism was thrown to the four winds. The dog was dead, its heart was pierced (or at the very least its internal organs were punctured and bleeding profusely) by the jagged wooden shaft of a broken baseball bat. It died lying on top of Donna and its corpse was so heavy that she struggled to push it off and get to her feet. And yet a few minutes later its mortal injuries have somehow been downgraded those of a nasty bruise and the animal is able to summon the strength to leap through a pane of glass to have one last go at its prey, and be handily silent in its run-up to the window. Yes, I know it's rabid, but come on…

And then there's the final shot. On the Blu-ray, Teague does provide some justification for the decision to end the film on a freeze-frame of Vic arriving too late to be of any goddamned use to anyone, walking up the farmhouse steps and reaching out for Donna and the unconscious Tad. It's a moment of possible reconciliation between them, one that leaves their future open to audience speculation, and for my money that's no bad thing. After what they have been through (their marriage was on the rocks after Donna had an affair with the local stud), a pat, happy-ever-after ending would have been an insult, and this certainly isn't that. But it also lacks the emotional payoff that Tad's unexpected resurrection deserved, Donna's initial elation at his revival having been prematurely undercut but the sudden appearance of the zombie Cujo. By all means give us an ambiguous ending, but make it a proper one, don't just bring the film to a halt as if someone has accidentally hit the pause button, at least before we get to the scene in which we really get to wonder what effect of this experience will have of this family's future. When watching the film again, I couldn't help thinking of that extraordinary final scene in David Cronenberg's A History of Violence (spoilers for this film immediately incoming), when Tom Stall returns home after a killing spree at his old boss Richie Cusack's compound to face a wife and son who have discovered that the man they thought they knew is a completely different person with a terrifying past. And what do they do? They sit down and eat dinner. Yet in that simple sequence, so much is implied just by the looks they exchange and their body language that I emerged from the cinema reeling at its implications. I was full of questions, but absolutely felt that I'd been given the material I needed to provide my own speculative answers to them.

So does my dissatisfaction (and I must reiterate, possibly for the hundredth time on this site, that it is my dissatisfaction, not the scientifically provable critique that too many like to claim their own opinion is) with the ending spoil Cujo for me? Not in the least. Yes, it's the last thing we see before the credits roll so remains the freshest element after every viewing, but so much of what has preceded it is just too damned good for the final scene to do any real damage. It's also worth noting that none of the points of contention are deal-breakers in their own right: the decision to have Tad live makes sense for the movie; Cujo's resurrection may interrupt the trajectory of the drama but it doesn't completely derail it; and the final freeze-frame may prompt a “What? Is that it?” response, but the mere fact that it does leave this broken family's future open to audience speculation goes some way to mitigating the decision to stop the film there.

So what do I take away from all this pondering? I guess, when it comes to a good movie, a bad beginning may be easily forgiven and forgotten, and while an unsatisfying ending can do it more harm, there's also a good chance that it won't, at least in the long term. After all, that jolt of disappointment we experience when an ending doesn't work for us may stay with us for some time after the first viewing, but if the rest of the film is strong enough then we'll likely watch it again, and this time be ready for an ending that probably won't sting as much the second time around. That said, I still wish Priestley had let George Bird live. |