|

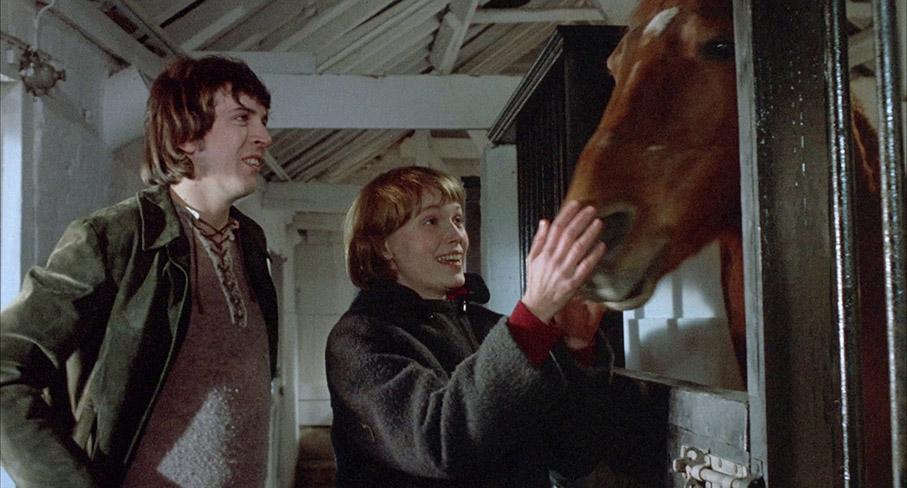

Having lost her sight in a horse riding accident, young Sarah (Mia Farrow) goes to stay with her aunt and uncle (Dorothy Alison and Robin Bailey) at their sizeable estate in the restful quiet of the English countryside. She's visited there by her boyfriend Steve (Norman Eshley), who risks re-awakening past trauma by getting her back onto a horse and taking her riding, which she enjoys. While they are out, the house is visited by an unidentified man who has been stalking the family. When Sarah returns, she is unaware that her aunt, her uncle and her cousin Sandy have all been murdered.

It's perhaps no surprise that Richard Fleischer's 1971 See No Evil – which was released in the UK as Blind Terror (more on that below) – sometimes finds itself negatively compared to Terence Young's 1967 Wait Until Dark, in which a blind woman named Susy (played by Audrey Hepburn) finds herself terrorised in her home by sadistic sociopath Harry Roat (Alan Arkin). There are certainly obvious similarities in the setup, and Wait Until Dark was also a sizeable critical and box-office hit. It was also first past the post with the concept of a blind girl caught up in a fight for her life against a single unhinged and murderous male, and there is a critical tendency to credit ownership of an inventive idea to the first film to use it and by association suggest that any recycling of the concept must somehow be inferior by default. And while there's no question that Wait Until Dark was a belting thriller, I see no reason why a film as strong in execution as See No Evil should be cast in its shadow. The basics of the central concept aside, these are very different films and deserved to be seen not as rivals but as companion pieces.

While Wait Until Dark is driven forward by a plot to recover a doll containing smuggled heroin, See No Evil initially takes a more low-key and character-based approach, as we are introduced to Sarah, her family and her love interest and then given some time to get to know them. And while in Young's film, Susy is terrorised for a specific reason, the killer in See No Evil selects his target at random after his well-protected feet are splashed with mud by their car as it passes on its way to pick up Sarah from the station.

Fleischer elects not to show the murders, but instead exposes their aftermath in a series of genuinely chilling reveals, as Sarah moves around what she believes is an empty house and passes within a few inches of her slaughtered relatives. One particular near-discovery involving a bathtub actually prompted me to let out a yelp, whilst another tells you everything you need to know through slow zooms onto an abandoned mower and an empty pair of Wellington boots. Most nerve-wracking of all is the broken glass that has been left scattered over the kitchen floor that the shoeless Sarah repeatedly just misses but that you just know will catch her out at the very worst moment. Fleischer absolutely milks all this for tension, then seemingly offers Sarah an avenue of escape (albeit from a situation that she doesn't realise she's in) and then deposit her right back into it again and crank up the tension further to the level of a direct threat on her life.

Playing blind is always a tricky thing to get right for a sighted actor, but Mia Farrow does an admirable job here, and having delivered a masterclass in vulnerability and fear in Rosemary's Baby, she does likewise here with such conviction that there were times that I almost wanted to climb into the screen and give her a reassuring hug. She's backed by a solid British supporting cast, which includes early film roles for Michael Elphick and Paul Nicholas, plus a number of familiar faces that will have you screwing up your face in an effort to recall their names and just what it was that you last saw them in. It's handsomely photographed by The Offence, Wise Blood and The Exorcist III cinematographer Gerry Fisher (a few of the countryside exteriors really sparkle), while the smartly structured script was the work of The Avengersalumnus Brian Clemens, who the same year would write the smarter-than-it-sounds Dr. Jekyll and Sister Hyde for Hammer, before going on to write and direct his own cult horror feature in the shape of Captain Kronos – Vampire Hunter (1974).

Not everything has aged so impeccably. The fact the killer's identity is continually shielded (he's identified only by a pair of cowboy boots bearing a white star insignia), which as anyone with a few giallo thrillers under their belt will tell you means it's probably someone we know but don't suspect, paving the way for an “Aha!” reveal in the final act. Whether this is or isn't the case here is not for me to say, but it does allow for some rather neat misdirection that plays on a very real prejudice of the day (and is doubtless still held and expressed by some in these unenlightened times). I was also given a bit of a start by the initially loud blasts of Elmer Bernstein's score, which provides the title and a couple of the early scenes with the sort of musical accompaniment that I'd usually expect to find on a western or an action-adventure tale, though this does give way to some unsettling off-key piano tinkling that nicely underscores the tenser scenes.

Coming back to See No Evil for the first time since I first saw it as a teenager made me wonder just what those reviewers who were so dismissive on its release really had against it. It's stylishly but economically directed by Richard Fleischer, who adapts effortlessly to his locale every bit as effortlessly as he did with his masterful 10 Rillington Place, delivering a film that feels authentically British but is handled with an American independent verve and eye for detail. Some will have an issue with Sarah's traditional woman-as-victim role (though it's worth remembering when the film was made) and the exploitation of a disability to intensify her terror. But for those who are game, this is an impressively acted, tightly constructed and seriously tense thriller that grips from an early stage and never let's go, right up to the deceptively straightforward but heavily subtext-layered final shot.

It's an Indicator release. Do I need to go on? As we've now come to expect, the .1.85:1 HD transfer on the Blu-ray here is in terrific shape, boasting admirable sharpness and a crisp level of fine detail that shows no sign of artificial enhancement, very well balanced contrast and solid black levels, and largely naturalistic colour but with that slightly warm tone that you often got with film but that you still rarely if ever see even on the best digitally shot features. The image is clean, with only the odd dusts spot remaining here and there, and a fine film grain is visible throughout.

The Linear PCM 1.0 mono track is very clear and clean, with no trace of background hiss or damage and no distortion even on the louder dialogue, effects or music, despite that very slight treble bias that is normal for pre-Dolby films of this era.

Optional English subtitles for the deaf and hearing impaired are available.

Blind Terror (87:30)

In the UK, See No Evil was released as Blind Terror, which is essentially the same film but with a few editorial changes to some scenes in the first 40 minutes, and even has some footage that is not in the See No Evil cut (the same is true of See No Evil in relation to this cut). Some of this material had to be sourced from a standard definition original, which does result in the occasional shift in quality, but it didn't bother me in the slightest. I'm not quite sure what the reason was for these changes, as they do not significantly alter the film, nor do they soften material that might have been considered too strong for us sensitive Brits. I could list the changes in detail, but there's a special feature on the disc that does that far more effectively than I could in mere words. As Blind Terror has been included on this disc in its entirety and is of identical quality, you can choose to watch whichever version you prefer.

The Two Versions (7:22)

Written and directed by Michael Brooke, this excellent featurette outlines the precise differences between See No Evil and the alternative Blind Terror cut by running the altered scenes side-by-side in their entirety, with further detail and contextualisation provided by captions. Couldn't be clearer.

Norman Eshley on 'See No Evil' (11:19)

Actor Norman Eshley – who plays boyfriend Steve and had aged with the same air of seasoned cool as David Warner – recalls unexpectedly being offered the role after director Richard Fleischer saw him on stage and telling a couple of porkies about his horse riding skills. He has nothing but praise for Fleischer and writer Brian Clemens, and has a sprinkling of entertaining anecdotes about the shoot. An enjoyable extra.

Alternative Italian Title Sequence (2:25)

Apart from bearing the Italian title, Terrore Cieco, the sequence also sports a localised opening shot of the cinema billboard, where the suspect double-bill of The Convent Murders and Rapist Cult has dispensed with its unpleasant sounding supporting feature and Italianised the main feature into Assassinio al Convento.

Theatrical Trailer (1:18)

A compacted version of a later sequence that I've made no mention of above, and with good reason, as it would act as a spoiler. Save for after the film.

Original Promotional Material

93 slides of production and promotional stills, plus a few international posters. One Italian poster, designed in the manner of a comic strip, is visually striking, but just a little bonkers.

On-Set Photography

34 images taken on set and location. These have been scanned from transparencies, some of which have sustained damage. We don't mind.

Booklet

A typically useful booklet accompanies the release, which begins with full credits for the film and a thoughtful (if spoiler-peppered – I'd read this only after watching the film) essay on the film and the filmmakers by Chris Fujiwara. This is followed by extracts from an article by Joyce Haber that includes an interview with Richard Fleischer, who reveals that he intended See No Evil to be a mix of Wait Until Dark and Les Diaboliques and offers his take on why the original score by André Previn (who was then married to lead actress Mia Farrow) was dropped. Hear No Evil looks at the issue of this lost score in more detail through extracts from articles and an interview with Previn from around the time of the film's release. Given that Previn's account of why his score was dumped differs somewhat from Fleischer's, this makes for very interesting reading. Finally, we have some extracts from contemporary reviews, both positive and negative.

A conceptually simple but well-made and intermittently nail-biting thriller bolstered by a first-rate central performance and a strong supporting cast. Once again Indicator has delivered the goods, with a strong HD transfer and a solid set of extra features. Definitely recommended.

|