"And right away on The Hill, the very fact that I cast him in it meant

something. And he was so thrilled to be taken that seriously for that kind

of a drama. And when he got to produce a picture of his own, The Offence,

a story he picked out, I was thrilled to be asked by him to direct." |

Director, Sidney Lumet

Interview with Sidney Lumet, DGA Quarterly 2007 |

Sean Connery is one of a very small number of genuine screen icons. Launched into the celebrity stratosphere after his debut as James Bond in 1962's Dr. No, Connery peaked as Bond in Goldfinger, the third (and for me the quintessential) film of the franchise, and then grew increasingly frustrated by the straitjacket the role began to represent. Using his star power to produce films he felt were more worthy of his participation, he starred in a real mixed bag of movies never really fully stretching his great ability as a character actor. But there was one underrated gem of a film from 1973 and it doesn't surprise me one bit that the great Scot himself singles out The Offence as his favourite of all those movies he's been involved with. Icons tend to be hired to lend gravitas and worth-by-association to a project and Connery rarely attempted to conceal his accent even when playing foreign roles. In 1982, I was working at a sound studio when Connery was hired to voice the World Cup documentary 'G'olé!' The director was nervous (well, anyone would be) and according to a second hand account, Connery said hullo, announced to the director that he wasn't going to take any shit, read the script undirected, and disappeared smartly after a very swift ninety minutes. Icons can do that. It was his casting in Sidney Lumet's The Hill that encouraged Connery the producer to hire Lumet. Damn fine choice.

I regard The Offence as one of the 70s' finest character studies. Connery plays Sergeant Johnson, a policeman whose experiences of the darker side of human nature have been unrelenting over the years. Consumed by the fear of his own nature, he unconsciously allows a suspected child abductor and rapist to get under his skin. The accused, Kenneth Baxter (a superb Ian Bannen) thrusts a metaphorical mirror at his adversary's animal aggression and Connery does not like what he sees. Bannen's innocence or guilt is never explicitly made clear. He's more an agent of Connery's psychological demolition than a would-be dead man in prison. The movie starts with concerned police officers trying to restrain Connery. It's all shot in slow motion with eerie sound effects. The unfortunate 'Dalek-stalk' milky visual effect is a little on the irritating side (it is essentially revealed as a thirty per cent superimposed fluorescent ceiling lamp – it's the signifier of a situation and man out of control) but director Lumet felt it was necessary until we are returned to non-clouded 'normal' vision as we close in on Connery as he says "Oh God, oh my God..." Bannen is carted off on a stretcher and, without an explanation (how I adore filmmakers who don't 'explain') we return to, presumably, a few days earlier when Connery is in charge of overseeing a frightened town being terrorized by a child rapist. Two things struck me about this second scene of anxious parents collecting their children from school. The first was shock in seeing Connery (still Bond in my younger eyes) in a suburban setting so much like my own home and environs when I was young. It was like kitchen-sink cinema with a giant at its core. Secondly, I still remembered the rather unfortunate spilling of the shopping shot. A woman has to stop to witness something from afar and the impetus was that she drops some of her shopping and while picking it up, she was able to see what she was supposed to see. I'm not sure if Lumet was having a bad day but it is so obvious that the actress throws her arm violently down to spill the shopping from her wheeled cart intentionally. It's not as if this derails the movie but in such a gem, it's unfortunate to find such a piece of silliness like this.

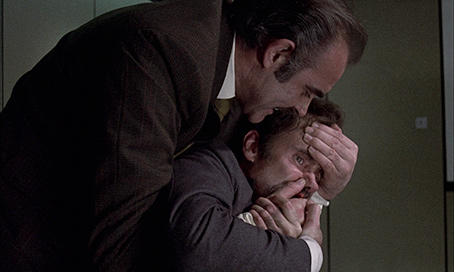

Right under the noses of the attending officers, another girl is abducted and a massive manhunt ensues. Connery breaks off from the other officers and manages to find the bloodied and scared girl in the bushes. It is this scene that I found so remarkable for the skill of its execution. I admit, in a casual viewing, there may be nothing remarkable but seen from the point of view of the craft of film editing, the scene is made more powerful by the timing of the edits. From this – the crying girl placed on Connery's sheepskin coat...

To this – her brave rescuer...

The scene starts with Connery shining his torch on the girl who then struggles as he tries to calm her down. But this is six foot two (and a half inch) Connery, with hands the size of dinner plates touching her face, encasing her shoulders, personifying the power he'd have over the weaker girl if he gave traction to his darker thoughts. In any other circumstances under a different director and perhaps with someone like Tom Hanks, the underlying morality would be crystal clear and free from subtext. The victim, the hero. Nice dividing line. But the editor, John Victor Smith, gives us one close up of Connery too many and holds it and holds it... This tips off the audience to something darker passing through the man's mind. This is immeasurably helped by a wonderfully powerful, anti-Bond, flawed human performance from a brave Connery. The longer we are on Connery staring at the girl, the more uncomfortable we feel. This ambiguity, all born from that one cut too many is oddly confirmed by a fantasy version of the scene, a brightly lit, fleeting thought from Connery much later in the film intercut with his confessions to his superior. The girl is lying down but she's smiling, not crying and he's still towering over her. This is character ambiguity beautifully conveyed. This is also a great example of the precision of a close up and how you can make the man who was James Bond into a man scared that he's the Soham girls' murderer, Ian Huntley just by timing things correctly.

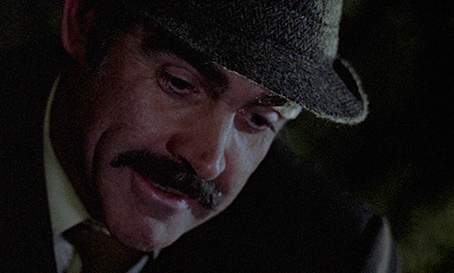

There is a scene about forty-one minutes in, which has stayed with me for many years. Connery is driving home. Whilst he navigates his car in the rain, we see trains thundering past and a young copper discovers the sadomasochistic murder of a woman tied to a bed, a macaw on the bedpost. Yes, the exotic south American bird. A child's arm leaks blood from the bars of a cot and an old corpse hangs from a tree. A body is lowered from a train siding and a car crash scene is intercut with repeated shots throughout. These are the images and cases playing through Connery's mind on a continuous loop. These are the images that are driving him to give unconditional freedom to his id – his animalistic nature that will be his undoing. During the interrogation, Ian Bannen's Baxter says to Connery; "You sad, sorry, little man..." No quote could be more ironically directed towards an actor like Sean Connery but boy, it works wonders. People afflicted with inner turmoil will go to extraordinary lengths to keep that turmoil from surfacing and breaking through the caldera of their psyches. After an hour and fifteen minutes, Connery smashes his head into a table imagining the victim but it's the idealised victim, a willing victim in his own fantasy. Lumet (or was it writer John Hopkins?) has the balls to show the victim brushing her head as if Connery's self-inflicted pounding is affecting characters in his own fantasy. This is sophisticated filmmaking, folks. To their great credit, I think of The Offence's scenes with Connery and Bannen as a slightly different and more violent take on McGoohan's television masterpiece The Prisoner, specifically the penultimate episode Once Upon A Time, a finely judged psychological duel between McGoohan's No. 6 and Leo McKern's No. 2... High praise. Bannen thanks the man responsible for his smashed up face for the handkerchief offered to mop up his own spilled blood. This is the stereotypical and perhaps spurious embodiment of the British character, down to a tee.

Each of the rest of the cast is utterly convincing. Trevor Howard, a stalwart British film icon before Connery, does a brilliant job as the superior officer sent to ascertain Connery's state of mind. These are policemen, not trained psychologists. At one point Connery crushes his superior's hand holding a cigarette burning him in the process. Have you ever felt so frustrated that hurting someone seemed to be the only route to their understanding your own pain? I have only felt, once in my life, that violence, and absolute violence, would be the answer to psychological paid inflicted with manipulative intent. It's a viciously strong compulsion. It's the explosion, the detonation to be rid of the black poison in your head. Vivien Merchant is superb as Connery's uncomprehending (but so wanting not to be) wife. Connery's line to her, "If you could put your hands into my mind and make it stop..." is almost graphically realised with the hand 'inside' Connery's head in the profile two shot. Her gradual breakdown is enthralling and you can almost taste the frustration between the two broken people. But in the end it's Connery's show and rightly so. His vulnerable and crushing breakdown next to Bannen just shows a range he'd never been asked or expected to reveal before and it's compulsive to watch such a big man in so much anguish. The weight of Bond also subtly plays a part here. Connery was never asked to play weakness (I don't count Finding Forrester but then that movie barely covered its costs). It seems his hits are when he plays the strong, confident macho type. This of course does two things. It adds to the fascination of the scene but it also keeps a potential audience away. Who wants to see James Bond having a breakdown? Well, I do. And so should you.

The first thing to note is that this is a dark film, not just in its tone but in its look, with Gerry Fisher's cinematography painting a picture of a glum England that is clouded permanently in shadow. The interiors are dimly lit and the light in the night-time exteriors kept to a convincingly realistic moon and torchlight level, and this is faithfully reproduced on the transfer on this Masters of Cinema Blu-ray. A word of warning. If you're planning to watch the film on a plasma screen then I'd wait until the sun goes down or you'll be struggling to see anything at times (I had to push the levels on the screen grabs or you'd have seen next to nothing). But if those viewing conditions are ideal (and they should be for any film) then the transfer feels absolutely spot on, with the exterior gloom and darkly graded interiors never swallowing up picture detail. Only in the exterior night footage is there a sense that some elements have been absorbed into the darkness, but even then this feels intentional. The image is as crisp as these light levels allow and certainly wipes the floor with any previous standard definition version, and the earthy colour scheme was clearly designed to be part of the film's moody aesthetic – check out the brighter colours of the lighting in the bar in which Sergeant Johnson is drinking with a colleague shortly before he is informed that another girl has gone missing, or the vivid blue of the car in which a schoolgirl is whisked away by her worried mother (see below). A fine job with no trace of damage or dirt, and framed in the original 1.66:1 aspect ratio.

The Linear PCM mono track does its job well for a British film of this vintage, being clear, free of noise and damage but displaying a slightly restricted dynamic range, with precious little in the way of bass response. The dialogue is always distinct and Harrison Birtwhistle's almost avant-garde score is clearly reproduced.

Also included is an isolated music and effects track, and this time around it's the Birtwhistle's score that benefits most from this option. Optional SDH subtitles are also available.

Christopher Morahan (8:29)

An interview with TV, film and theatre director Christopher Morahan, who directed the Royal Court Theatre production of John Hopkins' This Story of Yours, which Hopkins later adapted into the screenplay for The Offence. Morahan recalls first working with Hopkins on Z Cars (if you're too young to recall this groundbreaking police series, look it up), how Harold Pinter was instrumental in allowing them stage This Story of Yours at the Royal Court, and how their desire to bring it to the screen with the original cast was scuppered by the producers' decision to cast a name actor in the lead and Sean Connery's preference for Sidney Lumet as director. Morahan remains very pragmatic about this decision, praising Lumet as a filmmaker and stating without a hint of bad feeling that this is "the kind of thing that happens in the movie business."

Chris Burke (8:21)

Assistant art director on the film Chris Burke talks about constructing a large police station set on the relatively small sound stages at Twickenham Studios, having to reinforce one of the walls so it wouldn't buckle during the fight scene, and praises Lumet's attention to detail and realism. He also remembers Connery joining them in the studio bar after a day's filming and agreeing to stand a round of drinks as long as they listened to his golfing stories, and Lumet being open to ideas from anyone, his reasoning being that if he used it and it worked well then he'd get the credit anyway.

Evangeline Harrison (4:57)

The film's costume designer Evangeline Harrison remembers the film being the first in which Sean Connery didn't wear his toupee, which at one point led to him not being recognised by women he was waving at from the passenger seat of her car. She recalls Trevor Howard being lovely except when he was upset, when he would "roar like a dragon," and describes a costume designer's role as a cross between a psychiatrist and a donkey. And yes, she does explain what she means by that.

Sir Harrison Birtwhistle (10:13)

The film's wonderfully named composer, Sir Harrison Birtwhistle, outlines his unusual approach to scoring the film, which involved creating a collection of mood driven wild tracks with no specific placement in mind, recording and treating them using filters and varying their speed, and then finding locations in the film where some of them felt at home, a process he describes as being a form of cubism. He claims that the music of cinema is a cliché by necessity, and warmed my heart when he admitted that "I find it difficult to do what I do anyway without someone else telling me what to do."

Theatrical Trailer (1:51)

Was this really the original trailer? If so, then the studio were really taking a chance, as it consists soley of the opening sequence in which Sergeant Johnson's assault on Kenneth Baxter is discovered, complete with slow motion, circular light overlay and disorientating music, overlaid with a couple of key credits. Booklet

Headlining this booklet is a solid essay on the film

by Mike Sutton, who regards The Offence as one of Sidney Lumet's finest films (no argument here) and wonderfully describes the performances of fellow Scots Connery and Bannen as "so intense that they threaten to burn a hole in the screen." This is followed by an interview with Sidney Lumet by Susan Merrill from 1973 that starts off by commenting superficially on Lumet's home and furnishings but then covers some really useful ground. Also included are credits for the film, stills, and the usual guidance on viewing for those who still do not know.

A superb psychological drama from the 1970s and one of the brilliant Sidney Lumet's finest yet too often overlooked films, The Offence also showcases the supreme talents of Sean Connery and Ian Bannen at the top of their game, and it's never looked better than it does on this new Masters of Cinema Blu-ray. Highly recommended – just don't expect a comfortable ride.

|