| |

"It's about the most unsuccessful film I ever made. Unsuccessful by any standards. In R.P.M. I sought more than anywhere else to reflect the times in which I lived and I got caught very badly. R.P.M. didn't come off and it didn't ring true, and it didn't because it was attempting to join into the confusion of the times rather than take a step ahead and speculate on the reason for the confusion. That would have been more interesting. I habitually filmed stories that I felt were relevant to the times in which I lived, but this was already out-of-date by the time I finished and edited it. Everything was happening fast in the 60s. Too fast for me, it seemed." |

| |

R.P.M. director Stanley Kramer |

Note: There are spoilers ahead, so if you're new to the film – or at least new to campus protest films – then proceed with caution or skip to the technocal specs.

R.P.M., as anyone who works with cars or motorbikes or is old enough to have a record collection will be aware, stands for revolutions per minute. Just so you know, that's also what it stands for in the film under discussion here, but we're not talking about how quickly your engine spins around or what speed you need to set your record player at so the song doesn't sound as if it's being sung by excitable chipmunks. This time the revolutions in question are political, the sort in which governments and social systems are forcibly overthrown by the people. There is, however, only one revolution taking place here, and that's localised to a single building on a university campus, and before I start talking about the film and how it addresses the tumultuous social politics of the time in which it is set, it might be an idea to outline in more detail what it's about.

On the campus of an unspecified American university, a sizeable group of students has occupied the administration building and drawn up a list of 12 demands, which they refuse to discuss with faculty authorities until current campus president Doctor Tyler resigns his post. Unable or unwilling to resolve this latest issue, Tyler obliges. A meeting is called of the Board of Trustees to select a replacement, but the students have their own suggestions on this score. The first two on their list, murdered Argentinean revolutionary Che Guevara and Black Panther leader Eldridge Cleaver – are dismissed out of hand, but the third – F.W.J. 'Paco' Perez – is a Professor of Social Sciences at this very university.

It's a fact of art that a number films from the late 1960s have not aged that well, primarily due to fashions and slang that remain confined to that specific moment in history, and the fact that many of these films seem to have been made by people who regard the behaviour and manner of speech of the youth of their day as something curiously or even comically alien. So when I sat down to watch R.P.M. for the first time, I couldn't help but wonder how far I'd get into the film before I encountered something that dated it. I'm giving the opening song a free pass because it's expected and appropriate that a film set at the end of the 1960s would feature a number of contemporary tunes – hell, if you were making it today and setting it in that time period you'd likely do the same. No, I'm talking about an aspect that really dates it, something involving behaviour or attitudes that would no longer be deemed acceptable. Five minutes, as it turned out. When the notion of offering Paco the job is debated by the Board members, one of them reveals that this middle-aged professor has a fondness for sleeping with the female undergraduates. Woah! There you go. In the age of #MeToo revelations, there's an essay's worth of discussion in that plot point alone. As it happens, Paco's current partner is 25-year-old graduate student Rhoda. Oh, that's alright then. Are the Board members outraged? Are they hell. Apart from one quick bluster of protest from the Board's token progressive, these morally upstanding gentleman – who include in their number a priest, it should be noted – do not seem to have a problem with Paco's behaviour. Try that today and see how it plays, mister.

As if to underscore the outdated gender politics of this situation (Paco also expects Rhonda to keep house and cook his meals), we're then introduced to Paco himself via a close-up of his hand resting on Rhoda's sheet-covered arse as the two lie naked in bed together. Paco is then woken by a phone call requesting his immediate presence before the Board, where he is told of the situation and offered the post of campus President which, after briefly dancing around the perceived absurdity of the offer, he eventually accepts. His first meeting with the group occupying the administration building goes well. Paco's anti-establishment leanings have made him popular with the students and he is sympathetic to their views and promises to take their list of demands – most of which he admits are reasonable – to the Board for consideration. But when the final three demands meet with opposition and the students threaten to destroy the computer on which all of the University data is stored, Paco finds himself stuck between his sympathy for the revolutionaries and their cause and his new responsibilities to the Board and the student majority who are not part of the protest.

R.P.M. was one of a number of films made in the late 60s and early 70s that featured youth activism, the two most quoted on this disc's extras being Richard Rush's Getting Straight (which I've not seen for a good many years but remember quite enjoying) and Michelangelo Antonioni's Zabriskie Point. This was an era of campus protests, many of which were tied to the civil rights movement or the widespread opposition to the Vietnam War, but things took a distinctly dark turn when the Ohio National Guard opened fire on unarmed protestors at Kent State University, killing four students and wounding nine more. The incident inspired over 4 million students to participate in protest strikes, shutting down universities, colleges and schools across the country. Years later, by when student activism had become almost consigned to a moment in history, these films became compartmentalised as cinematic time capsules of days gone by. Recent tragic events, however, saw students across America take to the streets in protest at the free availability of the weapons used to carry out school shootings, while men and women of all ages have organised to highlight the issue of social inequality by invading and occupying the premises of culpable corporations and organisations. In some ways those campus protest movies thus seem less dated now than they did twenty years ago.

As I suggested above, however, what tends to more obviously handicap these films is the constantly evolving nature of youth culture, fashions and slang, which inevitably date any film in which they are prominently featured and prompt bemusement or ridicule from a younger modern audience with slang and clothing trends of their own. Some years ago, when teaching a class on the evolution of documentary filmmaking, I screened an extract from D.A. Pennebaker's ground-breaking record of Bob Dylan's 1965 British tour, Dont Look Back (and for the pedants out there, the apostrophe is missing from the film's on-screen title) and the first reaction I had from the students was amusement that Dylan referred to other people as "cats," a common enough term in the late 60s that has since fallen into disuse and thus sounds odd to modern ears. I'd thus argue that one of the strengths of R.P.M. is that it tends largely avoids saddling its would-be revolutionaries with the sort of hip language that often makes it hard to take such characters seriously today. Here screenwriter Erich Segal (together with uncredited screenwriter Rod Serling) and director Stanley Kramer do at least seem to recognise that such dialogue would over time become a distraction and risk making the points debated by Paco and the students seem facile and insincere.

Surprisingly, the students are also not presented as the usual cartoons of 60s rebellion, but as fully-fledged characters who believe in their cause and are able to debate points with Paco without sounding unreasonable or absurd. Yes, their most vocal members seem designed in part to each represent a separate aspect of contemporary protest, including the hardened revolutionary, the Black Power activist and the angry and distrusting feminist. But Kramer scores some more points in the casting of Gary Lockwood as protest leader Rossiter and a young Paul Winfield as his easy-going black compadre Steve Dempsey, both of whom – although technically too old to pass as undergraduates – bring a sincerity and humanity to characters that too often come across as unrealistically two-dimensional. They're also given the sort of dialogue to work with that invites us to understand and sympathise with their cause even as we might become frustrated at their seeming inflexibility, an intriguing reflection of the current political situation on both sides of the Atlantic.

So that's good, then. Not everything works as well. I debated whether to put that quote from Stanley Kramer at the head of this review, as it could seem as if I'm pre-empting my own dismissal of the film by offering up evidence from the director himself. See, even he didn't like it. That was not my intention. It's there primarily because, while I agree with some of the points that Kramer makes, I also think he's being overly hard on a film that I believe has as many positive qualities as it does elements that just don't click. I've already highlighted a couple of its strengths, and before I get onto the others I think it's worth addressing some of the ways in which the film stumbles. As ever, this is a personal viewpoint, and as someone who has been involved in political activism over the years, there is inevitably going to be some bias to this. Feel free to skip to the end at any time you please.

Narratively and structurally, the film is a bit of a plod, comprising as it does primarily of sometimes in-depth conversations between Paco and the students, Paco and the Board members, and Paco and Rhonda, each of which function almost as stand-alone set-pieces in which specific aspects of social, gender or racial politics are debated. What's under discussion is always of interest and the dialogue is often thoughtfully written, and the impact that these conversations and their fall-out have on Paco provides the film with its narrative progression. What's missing here, however, is sort of spark and energy of the debate scenes that pepper the films of Ken Loach, which are so politically relevant no matter when the film is set that I find myself wishing I could step through the screen and into the film to take part. Here I watched, I listened, I intermittently nodded my head or thoughtfully scratched my chin, then moved on to the next to see what it had to say.

One problem I had with Paco is that I never bought his transformation from rebellious professor to reluctant authoritarian, going as he does in just a few days from being a man sympathetic to the students and their actions to one prepared to ask the police to eject them from the building by force. Over the course of his career, director Stanley Kramer used the medium of entertainment cinema to confront and debate a range of social issues, including racism in The Defiant Ones and Guess Who's Coming to Dinner, the oppression of progressive thinking by religious fundamentalism in Inherit the Wind, and the threat of nuclear war in On the Beach, to name but a few. As this film unfolded, it seemed clear that Kramer saw something of himself in Paco, a progressive who sympathises with these new young radicals but who is part of a system that they want to tear down.

The simple fact that the students are three-dimensional characters and allowed to present their case without coming across as ridiculous really carries some weight here, but I was still left with the sense that while both Kramer and Paco have a real fondness for them and their distrust of authority, they don't really understand them or their actions, and the film never really explores the root causes of their discontent. Both Paco and Kramer seem caught in the middle ground between the radicalism of the would-be revolutionaries and the restrictive conservatism of an establishment represented by the all-male and suit-wearing Board of Trustees. The film also suggests that while the Board members are at fault for their unwillingness to even engage in meaningful dialogue with the students, those occupying the administration building are in the minority, something Paco tries to exploit by addressing those who have chosen not to participate in the protest and, we are assured, just want an education and are not so troubled by the social issues of the day. It's perhaps a little ironic that filming on R.P.M. was completed just three months before the Kent State shootings, and the protest action shown here to be the province of a minority had, by the time of the film's delayed September release, become a genuine force to be reckoned with nationwide. Hence, perhaps, Kramer's comment above about the film being out-of-date by the time it was released.

From the moment Paco has words with local police chief Henry J. Thatcher about possibly having to call on his services, it seems inevitable that the film will climax with the students being violently ejected from the building by riot police, particularly as this is how most real-world student occupations of campus buildings were concluded. On the commentary track, the learned Paul Talbot describes the riot that follows as one of greatest scenes in all of Stanley Kramer's impressive filmography, a point on which I couldn't disagree more. For me, this is the most bungled sequence in the film, with what should have been the hard-hitting impact of the police action seriously diluted by an attempt to present it as a subjective experience through the use of distorted shots, blurred imagery, slow motion footage and an inappropriately funky percussion score. This strips the scene of its realism and transforms what should have been a shocking and brutal confrontation into staged and choreographed action that stylistically kicks against how the film has played up to this point (with the exception of a misfired and thankfully short sequence in which Paco imagines his fellow academics as Alice in Wonderland-like characters). If you're looking for a text book example of how to film such a sequence for maximum impact, check out the way in which the real-world violence and mayhem of the conflict between National Guardsmen and protestors at the climax Haskell Wexler's brilliant Medium Cool was shot and edited.

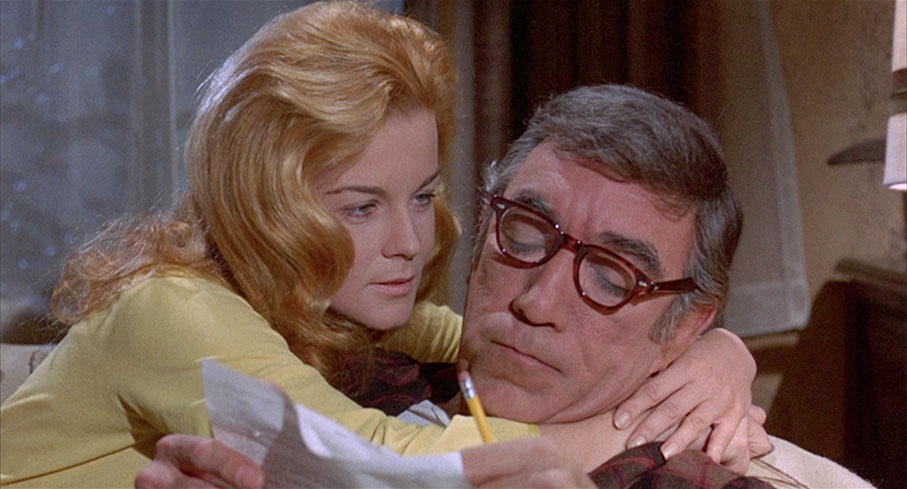

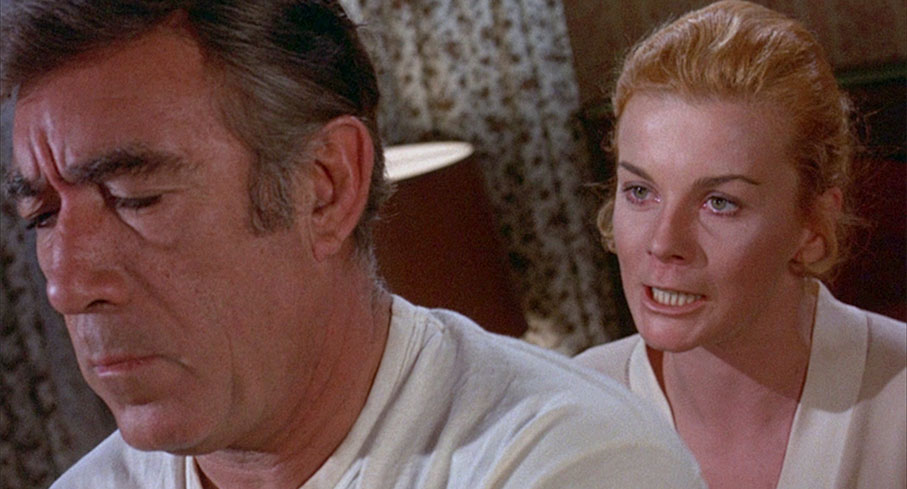

There are some interesting casting choices here. Anthony Quinn makes for a likeable enough Paco, but I'm not sure I ever really bought him as either a seasoned academic or an ageing Lothario (or, as he might be labelled now, sexual predator). Unlike, say, Donald Sutherland's Dave Jennings in National Lampoon's Animal House, there's little about Paco to readily suggest why female undergraduates would be so drawn to him (that's not a comment on Quinn himself, just his character's lack of charisma), though his easy-going banter with the students who are not protesting and his early encounters with Rossiter and Dempsey do give a flavour of his on-campus popularity. Ann-Margret, on the other hand, makes for a consistently lively and always interesting Rhoda, and while the early suspicion is that she has been cast as sparky eye-candy, she later comes into her own in her realisation that her relationship with Paco is taking her nowhere, and in the process delivers what for me was the film's strongest performance.

I've read a couple of spirited defences of R.P.M. that make excellent points, and for all the things that bugged me there are as many that mark it as a (flawed) film of note. As is pointed out in this disc's special features, it's rare if not unique for the issue of campus protests to be presented from the viewpoint of a well-meaning academic in an American film of this period. It's unusual to see the rebellious students portrayed with more depth and personality than the stereotypes that some of the more hostile contemporary reviews accused them of being. I'll freely acknowledge that my frustration with Paco's reluctant willingness to ultimately side with the system stems in part from my own past involvement with political action and the sometimes bemusing opposition we faced from those who once claimed to be supportive of our cause. That said, I'll also admit that the film does capture – a tad crudely but thankfully without mocking histrionics – the sort of internal political divisions and disagreements over priorities that can ultimately divide even the most outwardly solid protest group.

That Paco eventually feels he has to side with the campus administration plays as both a failure of middle-ground liberalism and a reminder of how the generation gap can lead to a breakdown of communication and understanding on both sides, which is still an issue at a time when elderly politicians (and disgraced comedians) feel entitled to dismiss the protests of school shooting survivors because they believe these brave and often eloquent individuals are too young to be able to hold considered opinions. In the end, both Paco and Rossiter have sound enough reasons to hold on to their respective viewpoints, as evidenced in the final conversation between the two men before the police are called to eject the students, a quietly captivating moment of truce in which they thoughtfully explore the gulf that now lies between them. There's not a trace of hostility here, and even a degree of mutual respect and understanding on both sides, but also no point of compromise on which an agreement can be reached to prevent the inevitable.

Yes, R.P.M. may stumble as drama and it may not explore the root cause of the students' discontent or a possible way forward for both sides, but its willingness to at least engage in the debate and allow both the protestors and the mediator to make their respective cases without overly criticising or mocking either does stand the film apart from its campus protest contemporaries. And at a time when political activism is once again on the rise, it offers a sobering reminder that, no matter how willing to debate and negotiate those in positions of power might seem to be, when it comes to the crunch, they'll do whatever they have to in order to crush the opposition and preserve the self-beneficial status quo.

Another strong 1080p HD remaster from Sony, framed in the film's original 1.85:1 aspect ratio and exhibiting no obvious signs of wear or distracting dust or dirt. The contrast is very nicely graded, with solid black levels but a pleasing tonal range that never feels harsh, and decent shadow detail even at night. The colour has pleasingly natural feel, and while the primes are quite vibrant, the palette has a slightly muted feel that reflects the fact that the autumnal exteriors were actually shot in mid-winter. Picture detail is good, and although the sharpness in some shots feels a little softer than on others, the best material is very good indeed. There is a fine film grain visible throughout.

The linear PCM 1.0 mono track has some minor range restrictions consistent with a pre-Dolby film of this era, but the dialogue is always clear and the music has a surprisingly bright feel. No damage or background hiss of crackle was audible.

As you would expect, optional subtitles for the deaf and hearing impaired have been included.

Audio Commentary with Paul Talbot

Human film encyclopaedia Paul Talbot once again delivers a dizzyingly detailed examination of the film and its makers, providing biographies of several the actors (including supporting players) and some of the key names behind the camera and examines the way several scenes are constructed and shot. Usefully, he provides details of Rod Serling's involvement and even quotes from his screenplay to illustrate how things were changed for the film, also identifying real world incidents from which the portrayed events were drawn, including the list of student demands. Ever the demon for detail, he even provides information on the computer on which the prop one made for the film was based. Even he doesn't know why Serling was eventually fired and received no credit, but he does have a telling quote from him made after he saw the finished product: "The film was awful, and I had a wonderful sense of wellbeing."

Two Sides of the Coin: The Songs and Music of R.P.M. (13:27)

An interview with R.P.M. score composer Barry De Vorzon, much of whose film work I'm still not familiar with but who I salute regardless for his terrific work on Walter Hill's The Warriors. He talks about the initially difficult process of making the move from rock musician to film score composer, how Stanley Kramer took a chance on him, then threw out all of his score except the riot scene music (I'm saying nothing), and how he bounced back by co-composing – with Perry Botkin Jr. – a number of songs whose lyrics still feel relevant.

Isolated Music & Effects Track

Come for the curiosity value but stay for those De Vorzon and Botkin Jr. songs and the voice of Melanie, though you'll have to fast forward quite often to get to them.

TV Spot (1:03)

An intriguing TV spot trailer that includes no footage from the film and instead lists words associated with the 60s protest movement that begin with the letters of the title.

Image Gallery

27 slides of promotional stills, five containing scans of the soundtrack album cover and four of posters.

Booklet

Plenty to get your teeth into here. Following full credits for the film we have a well-argued and detailed essay on the film and its making by Jeff Billington and an interesting interview with Anthony Quinn on the film from a 1970 article in the New York Daily News by Kathleen Carroll. A reproduction of the liner notes from the original soundtrack album is followed by extracts from three contemporary reviews, including a particularly hostile one from Vincent Canby of the New York Times, who included it on his list of the year's worst movies (a list that included Zabriskie Point and Tora! Tora! Tora!, which handily grants me a small snort of derision). As ever, the booklet is handsomely illustrated with production photos and artwork.

R.P.M. may be the only campus rebellion movie from this era that I hadn't previously seen when I popped this disc into my player, and my initial reaction was a largely negative one, the reasons for which I've largely covered above. But as I always try to do with any disc-based film that I've been charged with reviewing, I gave it a second look, and while many of my initial gripes still stand, I definitely found more to enjoy and admire this time around. It's a fascinating attempt to explore both sides of a generational and political conflict, one that doesn't quite come off but comes close enough at times to warrant a salute for its valiant effort. When it comes to special features, it's one of Indicator's more lightly packed releases, but what's here is very good and the transfer is up to the usual standard.

|