|

Director Laslo Benedek and producer Stanley Kramer's 1953 The Wild One is a key work of 50s American cinema. It was the first outlaw biker movie, the film that made an enduring movie icon of Marlon Brando, and controversial enough to be refused a certificate the UK for a whopping 13 years. It also has one of my all-time favourite opening shots, a static, low-angle view down one of those long straight American highways that seem to define the freedom of the open road, overlaid with a caption that warns of the shocking nature of the true story to come and then challenges us to make sure it could never happen again. It takes a while before you notice that something is coming down the road towards the camera, and even longer to realise that it's a gang of leather-jacketed motorcyclists, who ride up to and speed past the camera, narrowly missing it and in one case skidding and almost slamming the rear wheel into the lens. It's a shot that both hints at the threat that the bikers may represent and makes you wish that you could jump on a bike and ride along with them. Or is that just me? The film then cuts to one of the most iconic images in American film history, a three-shot of members of the Black Rebels Motorcycle Club that then hones in on club leader, Johnny Strabler. In case you somehow didn't know, Johnny's played by an impossibly cool-looking Marlon Brando, replete with black leather jacket and gloves, Aviator sunglasses and canvas peaked cap, sitting astride his very own Triumph Thunderbird and boasting the confident impassivity of someone well aware of how commandingly good he looks. The only thing that undermines this image just a tad is that it's all too obviously been filmed in the studio against a rear-projected background, though I should point out that this process would not have been seen as artificial or unusual in its day. It's one of a number of elements that require a modern viewer to see the film in the context of the year in which it was made to appreciate the impact it must have had in its day.

Johnny and his boys have been drawn to the Californian town of Carbonville by a motorcycle rally, one of whose races they ride slap bang into the middle of. After stealing one of the trophies, which Johnny quickly starts to treasure and which later takes on an important symbolic role, the gang moves on to the small town of Wrightsville, whose sole lawman is the easy-going Harry Bleeker (Robert Keith). The bikers are soon whooping it up, and while the townsfolk are at first uneasily tolerant of these boisterous visitors, when their rambunctious behaviour begins to get out of hand, local patience soon starts to wear thin. Only the Chief's brother Frank (Ray Teal), who owns the café in which the bikers congregate and freely spend money, seems happy for them to stay. Working there is Harry's attractive daughter Kathie, whom Johnny immediately takes a quiet shine to, something Kathie cautiously responds to in kind.

There's little question that for many of those coming to The Wild One for the first time from a 2017 perspective, the Black Rebels Motorcycle Club will not initially represent the most intimidating of threats. Subsequent outlaw biker movies and the likes of TV's Sons of Anarchy have upped the bar somewhat on what it means to have a motorcycle gang unleash holy hell on an unprepared township, and frankly you can see more disruption and violence on the average summer weekend in my town. The bad boy biker image is still a popular one, however, thanks largely to the activities of the Hells Angels Motorcycle Club and a small handful of other self-styled "one-percenters," a badge (or rather patch) of disreputable honour worn by outlaw bikers that sprang from a claim made by the American Motorcyclist Association that 99% of motorcyclists were law-abiding citizens. Yet it's the reputation of this small number of outlaw groups with which the wider majority of club bikers are too often tarnished, which is a bit much when you consider that American motorcycle clubs raise a substantial amount of money each year for a variety of local, national, and international charities.

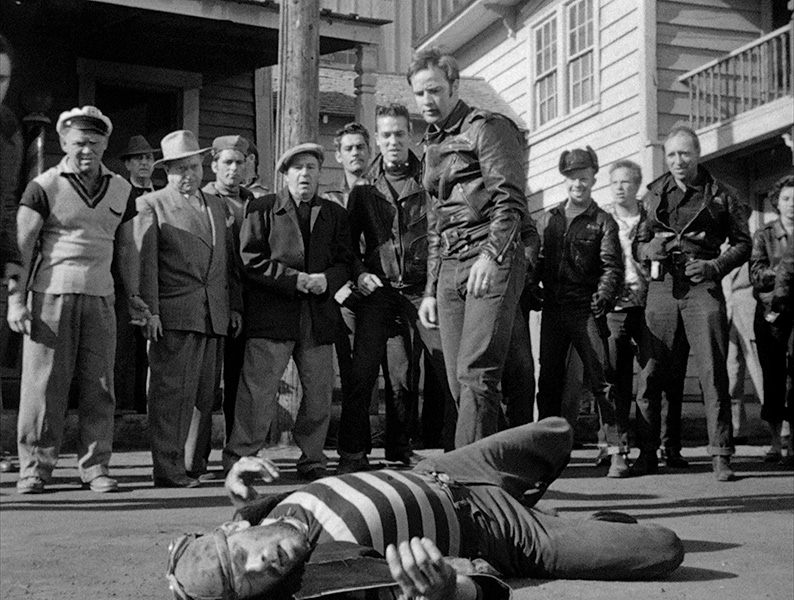

The Black Rebels Motorcycle Club clearly count themselves among the one-percenters, but seem to be driven more by exuberance than any real desire to harm or destroy. It's with the arrival of rival gang The Beetles – whose leader, Chino (played by an appropriately wild Lee Marvin), and Johnny have a long-standing grudge – that things really start to kick off. Johnny and Chino get into a fight, and the defeated Chino pulls an irate motorist from his car and ends up in the town jail for his trouble. After an evening of drinking and quietly brooding, both gangs then let rip and start intimidating the locals and wrecking property. When the bikers pick on Kathie, Johnny intervenes, but by now the locals have had enough and form an impromptu vigilante group to take on the invaders.

The film paints the bikers as outlaws from the moment the roll into town, black-dressed descendants of the outlaws of western legend who have traded horses for horysepower and have no respect for authority or anything approaching societal norms. Their outsider status is enhanced by their occasional use of 50s jive slang, the sort of "hey, daddy-o" hip talk that I always struggle to take seriously and that has dated as badly as the groovy hippie dialogue of late 60s American cinema. Yet in the context of the year in which the film was made and released it makes perfect sense, equipping the bikers with an almost alien mode of speech that bemuses the café's elderly barman Jimmy (William Vedder) and separates them from the locals in more than just the way that they look and behave. This is echoed further in their fondness for jazz tunes, which like the rock 'n' roll music to come was embraced by the youth of the day and regarded by the elders as everything from a corrupting influence to a potentially dangerous call to rebellion. The bikers' kick-against-society attitude is neatly encapsulated by the film's most justifiably famous exchange, when local girl Mildred (Peggy Maley) asks Johnny what he's rebelling against and he replies, "Whaddya got?"* It's a bit of a shame that the film then undercuts the sublime simplicity of this response by having Mildred repeat the entire exchange to Kathie. Yeah, thanks, but we got it the first time. Some have also been critical of the fact that these supposedly young tearaways are played by twenty-something and even thirty-something actors, though considering the average age of motorcycle club members today is probably somewhere in the mid-40s, I've never seen this as an issue.

The performances are all solid, but this really is Brando's show from his first eye-catching appearance. There's a memorable moment in Richard Benjamin's delightful first directorial feature, My Favourite Year (there are quite a few, as it happens), when Peter O'Toole's past-it Hollywood actor Alan Swann freaks out at the prospect of having to perform live on television and is reminded that he is an actor. His response is priceless: "I am not an actor, I'm a movie star!" In The Wild One, Brando excels as both, an über-cool icon for a whole generation of young film-goers, but one who brings a wonderful subtlety and control to what must have been a potentially showy role. Whenever he's on screen your eye is irresistibly drawn to him, despite the fact that he sometimes seems to be doing deceptively little, conveying more with a look, a posture or even a wipe of the eye than a good many others are able to with the full toolbox of acting techniques at their disposal.

The premise of a small town invaded and overrun by a biker gang – one based on a true incident, no less (more on this below) – may sound the stuff of exploitation cinema and did indeed go on to become just that. What differentiates The Wild One from its more disreputable descendants – quite apart from its classy direction, Hal Mohr's handsome monochrome cinematography, a string of solid performances and Brando's magnetic presence – is that it refuses to paint its characters or the situation in purely black and white terms, even having the nerve to suggest that supposedly respectable townsfolk can be as self-interested and prone to lawless violence as the bikers they regard as dangerous outlaws. Intriguingly, our sympathies can shift on scene-by-scene basis, as the fun-loving rebels of the early scenes take on a more threatening air when they (led by an uncredited Timothy Carey) intimidate a switchboard operator or encircle the frightened Kathie. Yet just as we begin really feeling for the besieged townsfolk, a group of them grab Johnny and administer what is far and away the most brutal beating in the film, then trigger a tragedy for which the fleeing and innocent Johnny is instantly blamed. It's he that proves to be the point of audience identification, cool and rebellious when we need him to be but ready to call a halt to the revelries when they get out of hand. With both the bikers and the townsfolk shown to be at fault and largely unrepentant for their actions, it's only Johnny who appears to learn and even grow from the experience, a journey of self-discovery that is first signalled by Brando's opening voice over.

It would be tough to make a case for The Wild One as genuinely great cinema, key elements having been dated by the arrival of social realism and the sheer volume of sometimes more convincingly brutal film portraits troublesome youth that have followed in its wake. But as Jeanine Basinger is quick to point out in her accompanying commentary, it's still a landmark work, one that paved the way for every outlaw biker film to come, gave us one of the silver screen's most endearing youth icons, and challenged the still widely perpetrated myth that society is inherently good and those who challenge or kick against it are bad by default. It also happens to still be rollicking good entertainment, and one of a crucial pair of films (the other, of course, is A Streetcar Named Desire) for which the young Marlon Brando continues to be justly remembered and celebrated.

Sourced from a Sony HD remaster, the 1080p 1.37:1 transfer on the Blu-ray in this Indicator dual format release looks terrific throughout, with beautifully pitched contrast, solid black levels and no evidence of black crush (how great it is to see night exteriors shot at night but still be able to see every detail on the riders' black leather jackets), crisply rendered detail and a fine film grain. The image is consistently clean and shows no evidence of wear or damage.

The Linear PCM 1.0 mono soundtrack is in similarly good shape, a little restricted on range but always clear and with no trace of background fluff or damage.

Optional English subtitles for the deaf and hearing impaired are also included.

Audio Commentary with Jeanine Basinger

Film historian Jeanine Basinger delivers an information and opinion-packed commentary on a film that she clearly admires a great deal and identifies up front as a landmark work. There's a lot of ground covered here, with considerable detail provided on leading man Marlon Brando, producer Stanley Kramer, co-star Lee Marvin, screenwriter John Paxton, and cinematographer Hal Mohr, with less extensive but still useful coverage of director Laszlo Benedek and several of the supporting cast. She contextualises the film well, aware of how hard it is now to appreciate the excitement that Brando generated in his early films and usefully reminding us that as an ultra-cool youth icon, he pre-dated James Dean, Paul Newman and even Elvis Presley. There are breakdowns of the purpose and effectiveness of specific scenes, background information on the story's journey from sensationalised newspaper article to finished movie, and a good deal more. A very fine companion to the film.

The Wild One and the BBFC (25:11)

Former British Board of Film Censors examiner Richard Falcon provides some welcome background information on the Board's decision to refuse the film a UK certificate and does so in impressive detail, outlining the social conditions and previous controversies that helped to make it such a problematic title. Nice to be reminded that Leslie Halliwell, creator of the exhaustive Halliwell's Film Guide and a writer and film programmer whose belief that film as a medium went into terminal decline in the late 60s was something I always had serious issues with, was an early champion of the film in his role as manager of the Rex Cinema in Cambridge. Another excellent and highly relevant companion to the film.

Karen Kramer Introduction (1:23)

The late Stanley Kramer's wife Karen provides an introduction to the film and appears to buy into the authenticity of the sensationalised true-life story on which the film is based, including the claim that the town was invaded by 4,000 motorcyclists (research suggests that only about 750 of them were bikers).

Hollister California: Bikers, Booze and the Big Picture (27:49)

Another highly welcome piece (which like several of the extras here appears to have produced in 2007 by Sony Pictures and licensed for this release), this featurette/documentary (how, exactly, do you differentiate the two?) explores the event that took place in Hollister, California in 1947 that was the original inspiration for The Wild One. Drawing largely on interviews with those who were there, including members of the Boozefighters and Top Hatters Motorcycle Clubs, it soundly debunks the exaggerations of The Cyclists' Raid, the Harper's Magazine story by Frank Rooney on which the film was based. The famous Life Magazine photo of a supposedly drunken biker at the height of this supposed riot is also confirmed to be a fake by Gus Deserpa, and as the man standing in the background of the picture, I guess he would know. What comes across in spades is that the whole affair was distorted out of all proportion by the press in order to sell newspapers (nothing's changed there) and that the relationship between the townspeople and the bikers was actually rather good and has remained strong ever since, with the town now something of a Mecca for American club motorcyclists. As hotel owner Catherine Dabo says, after claiming that one incident caused less trouble than that created by locals on the average Saturday night, "We were nice to them, and they were nice to us." Great stuff.

Brando: An Icon is Born (18:38)

Another Sony-produced featurette, this one looks at the film and specifically its iconic star, and includes interviews with filmmakers Taylor Hackford and Garry Marshall, actors Dennis Hopper and Elizabeth Ashley, and Stanley Kramer's wife Karen. There are also a couple of useful extracts from an archive interview with Stanley Kramer on working with Brando, whom he describes as, "a wondrous, wondrous thing to behold, with a scale from one to a thousand, from utter pathos to maximum violence – he could break your heart or break your leg." There's plenty of material that is unique to this extra, and further confirmation is provided that the residents of Hollister were actually rather fond of the bikers, in part because they spent so much money whilst in town.

Super 8 Version (20:00)

Another one of those truncated, Super-8 versions of the main feature that are becoming something of a regular feature on Indicator discs. This one is of particular interest, as not only does it seriously compress and thus massively over-simplify the film and strip it and its characters of every ounce of depth, it also adds an over-earnest narration that intermittently pops up to summarise missing plot points or state the bleeding obvious – "Chino takes the prize trophy from Johnny's bike. He sets up for a battle between the two leaders," the narrator says just after the dialogue has made the exact same thing clear. Stripping out every trace of Johnny and Kathie's attraction for each other also completely neuters the ending, but the narrator has a simplistic take on that too.

Theatrical Trailer (1:37)

"You'll thrill to the shock-studded adventures of this hot-blood and his jazzed-up hoodlums!" claims a trailer that describes Brando as "that 'Streetcar' man."

Image Gallery

A manually advanced gallery of 29 high definition publicity stills and 3 posters.

Booklet

Even by the high standards of Indicator booklets, this one is bristling with worthwhile material. First up we have Road to Nowhere, Road to Everywhere: America's Original Rebel Without a Cause by Kat Ellinger, an excellent essay on the film, its conception and some key differences between it and the story on which it is based. This is followed by a reproduction of a piece on the film written by Leslie Halliwell for the summer 1955 issue of Sight & Sound and an extract from his 1985 autobiography, Seats in All Parts: Half a Lifetime at the Movies, in which he talks in some detail about his decision to screen the film at the Rex Cinema in Cambridge. Next up we have a 1955 article by the film's director Laslo Benedek in which he passionately defends the film following the BBFC's decision not to certificate it, which is followed by a pair of contemporary reviews by Penelope Houston and Gavin Lambert from Monthly Film Bulletin and Sight & Sound. Credits for the film and publicity stills have also been included.

As someone who used to hang out with bikers and who still thrills at the sound made by a beefy motorbike (but curiously, has never owned one), I've a special fondness for biker movies, and for all its dated elements, when it comes to this particular subgenre The Wild One is still the daddy. It really is the quintessential Brando-as-icon movie, and it's unlikely you've seen it look anything like as good as it does on the Blu-ray in Indicator's dual format set, which also sports and an excellent collection of extras. This is part of movie history and comes highly and enthusiastically recommended.

|