|

– Part 1: The Rebel –

| |

'A great artist must have sensitivity . . . must have some knowledge of suffering . . . Tony had it. It showed. He never did anything that wasn’t real and true . . . There wasn’t a speck of phoniness in his whole body.' |

| |

Frankie Howerd |

| |

'And did you get what/you wanted from this life, even so?/I did/And what did you want?/To call myself beloved, to feel myself/beloved on this earth.' |

| |

Raymond Carver, Late Fragment |

Let’s start at ground level and work upwards. Being human like the rest of us, our heroes will inevitably have feet of clay. This commonplace characteristic adheres to entertainers more than most, perhaps to comedians most of all. That, along with the difficulty or futility of explaining humour, helps explain why most books and films about comedians fall as flat as Tony Hancock’s feet. Clay they were, and he hated them: ‘They flap about . . . they’ve been put on wrong. They don’t join at the ankle. I can feel them flapping like a penguin’s.’ He didn’t much like his handsome mug either. His BBC producer Dennis Main Wilson called him ‘frog face.’ Hancock’s feet tell us something about his insecurities and self-deprecating humour. They also hint at his worldview and attitude to fame: ‘Underneath the hand-made crocodile shoes there are still the toes.’ The devil, as they say, is in the detail.

David Dimbleby once interviewed Ted Heath about different kinds of wheat: ‘I had tried to absorb the details of these arcane subjects but was still nervous about the interview. I adopted a technique that I had read about somewhere. If you are nervous of a person in authority, do not be cowed. Think of them naked and you will realise they are just another human being like you. The interview itself passed of well enough, the aftermath less so. The night after the programme, I had a disturbing dream in which Heath appeared before me naked, as I had tried to imagine him. I’ll spare you the details of that encounter. but it warned me against ever again using that particular technique for calming my nerves.’

Laughter may be universal and absolute, but it is also subjective. Humour really is hard to describe, and those who call Hancock a ‘comic genius’ have some explaining to do. Regrettably, more time and energy has been spent trying to explain Hancock’s death. By focusing on the distressing details of Tony Hancock’s suicide in 1968, the various biographies, dramas, documentaries and monographs about him all butt up against both the inscrutability of an abnormally complex man and the ungraspable nature of all human animals. That quandary bedevils the entire industry that has built up around the Hancock legend and often spills over into intemperate speculation. An accompanying stony emphasis on Hancock’s various very human failings can slide into the kind of character assassination that eclipses constructive appreciation.

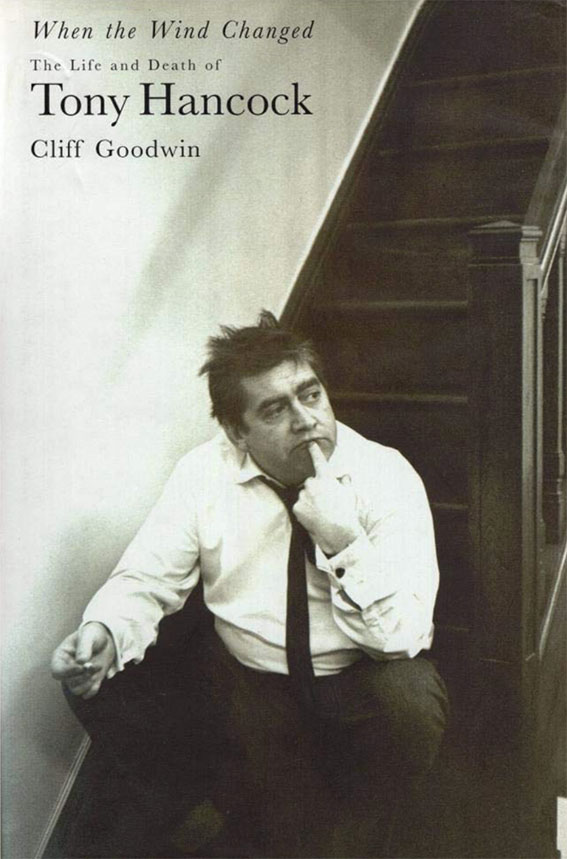

Neither Cliff Goodwin’s groundbreaking, if orthodox and slightly screwy When the Wind Changed: The Life and Death of Tony Hancock (Random House, 1999) nor John Fisher’s exemplary, more sagacious and sanguine Tony Hancock: The Definitive Biography (Harper Collins, 2008) entirely escape such snares. Big publishing houses demand their pound of flesh, don’t always baulk at sensationalism and titillation, may seek to profit from the prurience of potential readers, and, who knows, may lead authors with more edifying and ethical designs than their own astray. B.S. Johnson felt the term ‘business ethics’ was oxymoronic (Samuel Beckett said, simply, ‘I have a strong weakness for an oxymoron’).

Be that as it may, both books are indispensable to anyone trying to grasp Hancock’s abstruse, evanescent personality. They advanced the cause though, contain acute insights and invaluable information, and are shimmering goldmines of quotations. The Goodwin Life, for example, helpfully reproduces, for the first time, the BBC transcript of Hancock’s 1960 Face to Face interview with John Freeman – which many feel fatally exacerbated Hancock’s tendency toward punishing self-criticism.

[Although neither book features in-text citation, endnotes or footnotes, I gratefully draw and quote from them below. These are not works of scholarship, thankfully. Where useful, I also quote from the interview with Hancock’s scriptwriters Ray Galton & Alan Simpson conducted by Colin West and contained in Hancock’s Half Hour (Woburn Press, 1974), and their own introduction to The Best of Hancock (Robson Books, 1986)]

Australian TV producer-director Eddie Joffe – whose wife, Myrtle, discovered Hancock’s body after his death at the Joffe family home in Sydney, and to whom Hancock addressed his suicide notes – can be forgiven the forlorn attempt at catharsis contained in his book Hancock’s Last Stand. And, after all, someone left behind must keep a record.

The BBC’s 2008 film Hancock and Joan was based both on Joffe’s book and Lady Don’t Fall Backwards, the memoir of John Le Mesurier’s second wife, Joan – with whom Hancock had a final, brief, and violent affair. Although redeemed by the perceptive performances of Ken Stott as Hancock and Maxine Peake as Joan, Hancock and Joan follows a familiar pattern and focuses on Hancock’s last days, depression and alcoholism, at the expense of the work. So, too does the BBC’s conventional 1999 drama Hancock starring the excellent Alfred Molina as Hancock.

Writer Stephen Walsh and cartoonist Keith Page’s graphic novel Hancock: The Lad Himself (B7 Comics, 2023), thankfully, provide a more nuanced and innovative approach. So, too, does Ashtar Al Khirsan’s wonderfully evocative and deeply moving film The Unknown Hancock (BBC, 2005). Al Khirsan deftly walks a tightrope pulled taut between respect for Hancock’s artistry and recognition of the paradoxes in his behaviour, advisedly shimmying away from hagiography while treating the problems of addiction with the understanding they demand.

Al Khirsan was also lucky enough to be in the right place at the right time and was able to interview many Hancock insiders now no more. Luck played no part in her accomplished and sensitive use of archive footage. Sadly, she tells me that the film, of which she is justifiably proud, remains mired in copyright quicksand. A gorgeous montage featuring contested still images of Hancock and Sid James in rehearsal means it cannot currently be shown. That strikes me as one of those insults to the commons that diminishes us all and is especially galling in Hancock’s case.

In the BBC’s 1985 Omnibus film From East Cheam to Earl’s Court, the actor Bill Kerr, one of Hancock’s many foils on Hancock’s Half Hour, says, ‘What I would like to say about Tony is that he was part of us all . . . of every man and every woman that was watching. . . you only had to listen to [him] for five minutes and you realised he was talking about you.’

| An Echo of Remembered Laughter |

|

Hancock was also talking about his times. Given the low-grade dross that now flows remorselessly from our TVs, it is salutary and saddening to regard a period before dumbing down, infotainment, multimedia franchising, reality TV, smoke-and-mirrors commercial propaganda, snake oil product placement, cheap-trash programmes on cookery, consumer lifestyles, fast fashion, property, and, generally, money-money-money. The era in which Tony Hancock worked his magic now appears as a TV golden age. Yes, cigarette smoke floated on fuzzy screens; homophobia, misogyny and casual racism seep through the crackle and grain, but Hancock’s Half Hour seems to arrive from another – more civil, decent and gentle – country.

If ‘nostalgia ain’t what it used to be’ and our most popular pastime is to haul celebrities off the pedestals on which we’ve foolishly placed them, things aren’t improved by certain problems related to the free flow of information. Where Hancock is concerned, myths multiply and challenges to them decrease to the point that a new 21st century version of Flaubert’s Dictionary of Received Ideas is necessary. Given the competition between facts and disinformation, and the fact that so many details are available to so many so easily, it can sometimes feel as though everyone knows everything and nothing simultaneously. Better, perhaps, to say too much to the knowing than too little to the unenlightened.

With apologies to the Tony Hancock Appreciation Society (THAS) then, to details. Born in Birmingham but raised in Bournemouth, Hancock cut his distinctly irregular, very British comic teeth in disappearing worlds that echoed earlier worlds long gone – in wartime mess halls and on troop ships, in touring troupes that recalled the days of Music Hall, in musty seaside theatres that clung still to a vanishing vaudeville tradition, in Calling All Forces and Workers’ Playtime broadcasts at a time when ‘the wireless’ was still the dominant medium. Hancock paid homage to the old variety pros and film stars of yesteryear in his every performance, but nowhere more so than in Variety Ahoy and The Punch and Judy Man.

He absorbed the deeply democratic humour of those lost worlds while fighting for laughs in RAF Gang Show concert companies, on the road and in tatty digs across the land, and in front of raucous ruthless audiences at venues like the Glasgow Empire – a.k.a. the ‘comics’ graveyard’. It may be there that he developed the white-knuckle stage fright that afflicted him to the end and, his preferred remedy being self-medication, helped hasten it. In such settings Hancock soaked up a salty humour rooted in the urban working class, accompanying communal sing-alongs, shrouded in smog and smoke, and arising primarily from London’s back-street boozers and the back-to-backs of the northern industrial heartlands.

Hancock’s big break came, in 1951, with a starring role in the radio series Educating Archie, in which he played a disgruntled tutor to a wooden dummy operated by ventriloquist Peter Brough. There was more than a touch of vaudeville to it all and Hancock found it a tad infra dig. When he finally emerged into the modern world in his own right – initially on radio and television in the 50s and finally in film in the 60s – he carried traces of that earlier time-honoured popular humour with him and within him.

As if that weren’t enough to endear Hancock to his public, he embodied the spirit of mutual respect and collective strength that had solidified under conditions of wartime adversity and remained resilient under post-war austerity. He also personified a shared experience of the accelerating social changes that would flower in the sixties. Not bad for a public schoolboy outta Bournemouth, albeit one with a ubiquitous chip on his shoulder. Ten years after the war had ended, with deference in retreat and rationing easing, the character Hancock and his brilliant scriptwriters Ray Galton & Alan Simpson created – Anthony Aloysius St John Hancock – who immediately struck a resonant chord with an adoring public.

| H-h-h-Hancock’s Half Hour |

|

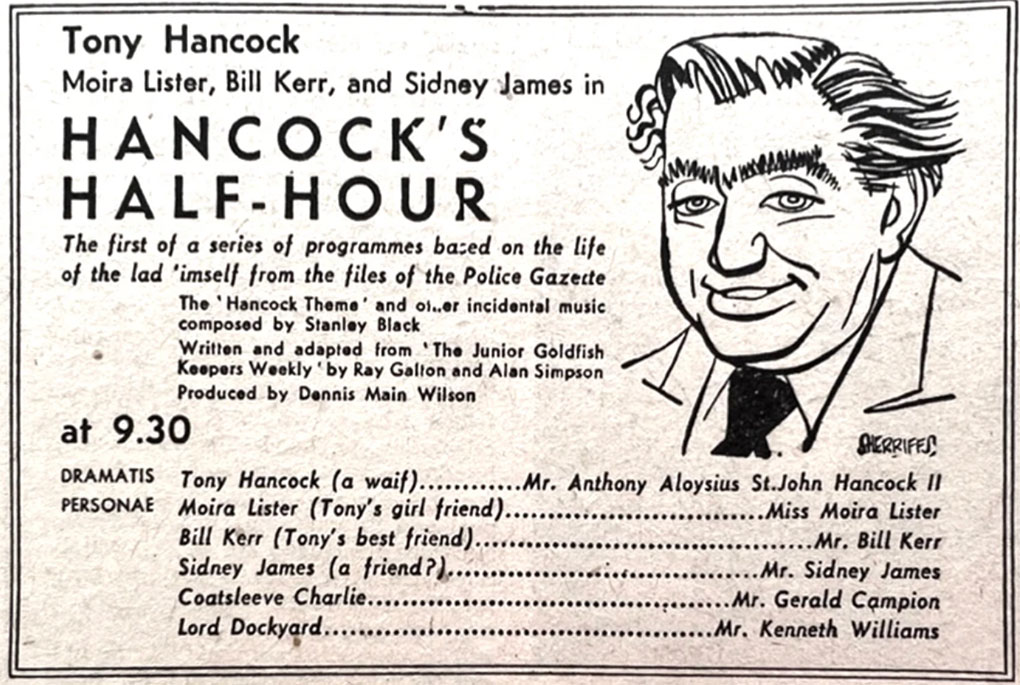

Between 1954 and 1961, Hancock, affectionately known as ‘the lad ‘imself’, the English Everyman and Nowhere Man of 23, Railway Cuttings, East Cheam was a cherished household name. The love flowed both ways, so it is no surprise that Hancock soon found a soft spot in the nation’s heart or that the BBC’s Hancock’s Half Hour programmes came to be seen as essential listening and viewing. Bob Monkhouse, whose early radio scripts helped launch Hancock’s career, said of the days when millions dashed home on a Friday night to catch the weekly TV broadcasts said, ‘His show emptied more pubs than the rise in the price of a pint.’

That the 13 unsuccessful episodes of ATV’s 1963 series Hancock were of an inferior quality can partly be blamed on new scriptwriters and is testament to the extraordinary talents of Ray Galton and Alan Simpson. Hancock and ‘the boys’ were bright-eyed and bushy-tailed when they found fame and fortune. Their young dynamism generated a spellbinding effusion of comedy magic before advancing age determined dissipation of their energies and brought an end to the whole fantastic enterprise.

Largely eschewing the pantomime catchphrases and funny voices of the likes of Kenneth Williams (‘Stop messin’ about’) and The Goon Show gang (‘Ying tong idle i po’), Hancock and Galton & Simpson deftly upended the conventions of pre-war comedy. Despite the importance of his gifted writers, Hancock almost single-handedly invented character-based situation comedy by layering into his lugubrious character a new ingredient uniquely his own: irreverent, tart, subdued but sardonic anger – at asinine authority, fate, officialdom, the rules, even at his own puffed-up pomposity and unsophisticated cultural pretensions.

Hancock was a rebel long before The Rebel (1961). He recalls Marlon Brando’s famous retort to the question ‘What are your rebelling against, Johnny?’ in The Wild One (1953): ‘Whaddaya got?’ When he said, ‘I cudda been somebody. I just didn’t feel like it, that’s all’ he referenced the Brando of On the Waterfront (1954) too, and when Harold MacMillan said, ‘You’ve never had it so good’, it’s as if Hancock raised his bushy eyebrows and, replying for the residents of dingy Railway Cuttings and millions beyond, said, ‘Stone me, have you gone raving mad, Mush?’

He represented a growing defiance of docility and compliance. As if by magic or osmosis but, if truth be told, due to having put in the hard yards on a hundred stages in front of a hundred hostile audiences, Hancock caught the popular mood and had the common touch. The East Cheam setting Galton & Simpson invented for Hancock’s Half Hour deliberately distanced him from the reality of well-heeled suburban Cheam. He was one of those rare comedians who only needed to raise an eyebrow or furrow his brow to have people in stitches. He scarcely needed to speak because everyone knew exactly what he was thinking – because they were thinking the exact same thing. The enraptured popular response to Hancock’s humour pivoted on that thrill of recognition. People loved him because they saw in him and his character traces of their colleagues, lovers, neighbours, partners, relatives, and themselves.

The poet Adrian Mitchell argued that ‘Most people ignore most poetry because most poetry ignores most people.’ The poetry of Hancock’s comedy upended that equation. He respectfully attended to real people – admirable, idiotic, hopeful, despairing – and they warmed to him in return. It was said that Gracie Fields didn’t so much produce excitement on demand as have it bestowed on her by her audiences. If ‘the Lancashire lass’ borrowed her enthusiasm, energy and confidence from her audiences so, too, did the likes of, say, Billy Connolly, Les Dawson, Chic Murray, Stanley Holloway, Hancock himself, and his idols Chaplin, Jack Benny, Max Miller and Sid Field. Theirs was a comedy of and for the people.

| The Astonishing Mr Hancock |

|

Hancock’s quixotic personality, perfectly calibrated delivery and impeccable comic timing, flat feet and pliable face, hangdog expressions and expressive sad-glad eyes, absurdist aspirational delusions and unflinching honesty – all combined to lift comedy to the level of high art. As Galton & Simpson say, ‘When we were writing Hancock's Half Hour, Tony told us, “You're the writers, you write. I'm the comedian, I'll comede.” And, boy, could they write! Hancock was blessed with two daring, socially conscious writers who shared his view that rueful appraisal of reality was essential to great comedy. Like Hancock (initially at least, until alcohol blurred his vision), they saw the funny side of self-delusion and failure. As Alan Simpson said, ‘Failure is more interesting than success.’

Hancock was also ably abetted by a first-rate cast, notably, his ‘second banana’ Sid James – as a cheeky cockney wide boy à la Alfie Bass (a character straight out of the pages of Kathleen Hewitt’s wartime novel Plenty Under the Counter); Hattie Jacques – as Hancock’s indomitable secretary Miss Giselda Pugh; and Bill Kerr – his good-natured, if dim-witted Australian lodger. Hugh Lloyd, one of the seasoned supporting actors who also enhanced the whole, said that recordings of the Half Hours were a joy for all concerned and that Hancock was the only performer he ever worked with who regularly drew spontaneous applause and laughter from his fellow actors – at rehearsals.

In late 1959, Hancock astonished everyone again by breaking up the happy band. Driven by a restless urge to stretch himself and relentless drive for perfection, terrified that his character was solidifying into cliché, and fearing that he and Sid James were becoming a pat double-act, he jettisoned his sidekick. As Ray Galton says, ‘Hancock was not one for standing still. He wanted change, change, change. He wearied of what he thought was a Laurel & Hardy relationship between himself and Sid.’ It is to James’s eternal credit that they remained friends after the split and had only a single stand-up row – a heated spat over a game of pontoon.

The split with James was also precipitated by Hancock’s desire to reach international audiences. He felt that his trademark hats and astrakhan collared coat were too parochial and that the comic possibilities of Railway Cuttings had been mined to exhaustion. Exhausted and overworked himself, already drinking disastrously, he agreed to make one more series for the BBC – with the proviso that James was dropped.

If Hancock’s decision to break with James was as risky and ruthless as was widely claimed, it was also inspired. It paid dividends in some of the funniest comedy ever broadcast in Britain or, indeed anywhere. If the 104 radio and 65 TV Half Hours Galton & Simpson estimated they wrote were exceptional, Hancock’s final BBC series – made without James, shortened to 25 minutes, and renamed simply Hancock – was the stuff of greatness.

Hancock, relocated from a house in East Cheam to a bedsit in Earl’s Court to face the world alone, soared to new heights. That final flourish gave us masterpieces such as The Blood Donor, The Bowmans, The Lift and . . . Hancock Alone. And then, in 1961, he did it again, astonishing those in the know by dispensing with the services of Galton & Simpson. The two writers would press on to create Steptoe and Son, essentially a reworking of the Hancock character in a different setting – but not before they’d all three tried to conquer cinema as they’d already conquered radio and TV.

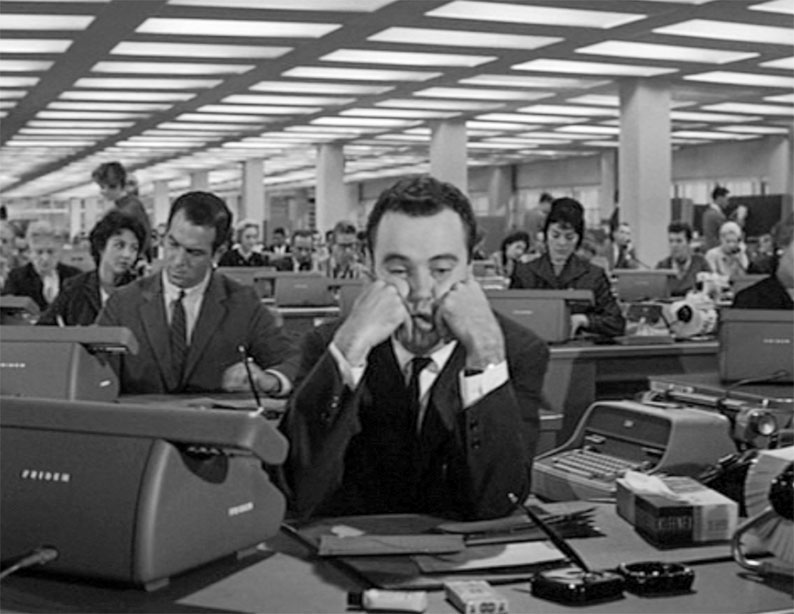

Having successfully navigated the testing transitions from stage to radio and then to television, Hancock, ever ready for change and challenge, was determined to make his mark in the film industry.The Rebel begins with a pair of reverential cine-references, to the railway terminal scene at the start of Jacques Tati’s Monsieur Hulot’s Holiday (1953) and to the opening office scenes from Billy Wilder’s The Apartment (1960). It would be instructive to know who conceived those deft touches. My guess is that Hancock was the knowing winker. Whether that’s true of false, we can better understand Hancock’s aspirations and fall from grace if we first consider his early relationship to the film and the film industry.

Hancock’s deep-seated love of cinema had begun far back in his boyhood. When he was just three, the Hancock family moved to Bournemouth. Hancock’s parents Jack and Lily first ran a laundry and then The Railway Hotel – a kind of racy Fawlty Towers at the heart of the seaside town’s lively entertainment industry and enthusiastic drinking culture. Hancock and his brother Roger, inevitably cold-shouldered by their busy parents and adults bent on adult pleasures, sought refuge in the local fleapits. Throughout his childhood, Hancock would regularly raid the hotel petty cash and steal off to cinema. ‘Provided it moved, I was there,’ he said, ‘And if I particularly liked a film, then I would go to see it time and time again. You might say I was discriminating. Or a very early example of what [came to be] described as a committed audience.’

Among his favourites were Chaplin’s City Lights (1931), which he called ‘the finest full-length comedy I have seen’, and the films of Will Hay – most strikingly, Good Morning, Boys (1937), in which a teacher takes his pupils to Paris. This is neither the time nor the place to revisit theories of authorship, but it’s worth noting that Hay was among those rare actors who can be said to have ‘authored’ the films they appeared in. Hay’s films were built around his personality, drew on a character and range of routines he’d previously honed on stage, and frequently credited him as writer or co-ordinator. The parallels with Hancock are obvious.

It may be stretching a point to suggest that Hancock internalised Hay’s example and later emulated it in professional life, but we can say that the films he watched in his formative years shaped his sense of humour. Hancock later recalled, ‘A double feature, half a bar of Palm toffee, and three and a half hours in the dark – that was my idea of fun.’ His affection for toffee would be superseded by a fatal taste for beer, brandy and vodka, but his fondness for cinema persisted and before long he’d grace the silver screen himself. In 1954, as Hancock entered his thirties and consolidated his success on radio, he secured a bit part in Orders are Orders – a B-movie Forces farce in which he appeared, as Lieutenant Wilfred Cartroad, alongside Sid James, Peter Sellers, Donald Pleasence, and Margaret Pryor (née Margaret Arabella St John Pook – can ya dig it?).

Hancock and his first wife, Cicely Romanis, visited the Astoria, Charing Cross Road to watch an early screening of Orders are Orders. Hancock says, ‘I asked the girl at the box office, “Do you think we’ll be able to get in?” She gave me a pitying look and said, “Get in? You can have the whole circle if you want it.”’ Picturehouse magazine felt Hancock ‘annexed the comic honours’ in the film, but Hancock was embarrassed by his part in it. For his part, Sid James said simply, ‘It was a bit of a stinker!’

In 1958, Hancock received his first offer of a film role, from the Rank Organisation - who were keen to cash in on Hancock’s growing popularity. The film, another stinker, ironically titled The Big Money (1958), was graced by Jack Cardiff’s cinematography and directed by John Paddy Carstairs, who had requested Hancock for the part of a portly prelate. Lord Rank once said, ‘I’m in films because of the Holy Spirit’, but Hancock had higher standards. He turned the part down flat, saying, ‘I’ve really made the grade. At 31 you’re the tops, they want you to play a 50-year-old bishop.’

Rank and John Paddy Carstairs would not take no for an answer though and returned to Hancock with a second offer. Again, he astonished them, by turning them down: ‘I took one look at the script. It said something about a [greyhound] racetrack attendant following the dogs around with a dustpan.' Sorry that kind of humour just isn’t me.’ Frankie Howerd wasn’t so choosy and took the part intended for Hancock. The film, again directed by Carstairs, was eventually released as Jumping for Joy (1956).

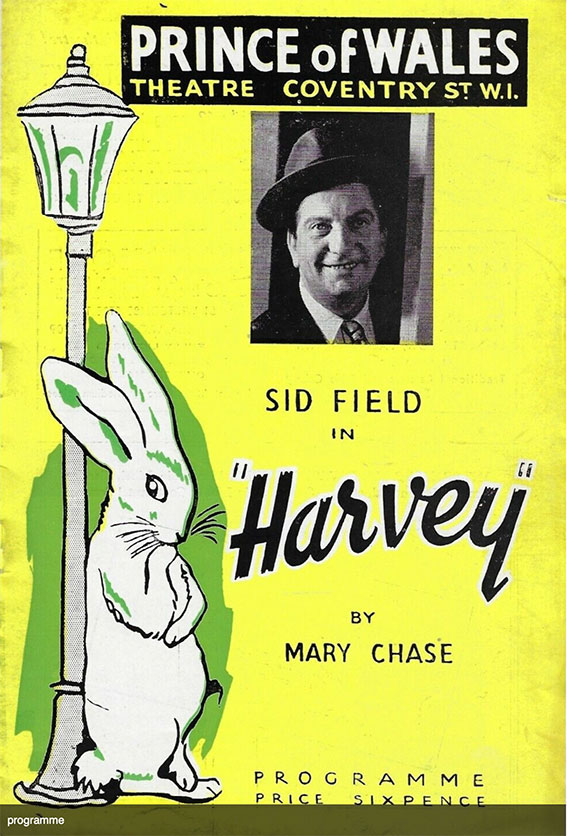

In 1958, Rank offered Hancock what would have been his first starring role – in a film about his idol Sid Field. Both Field and Hancock worshipped Charlie Chaplin, left indelible marks on comedy, failed to set cinema alight, and shuffled off their mortal coils in their mid-forties. Again, astonishingly, Hancock turned the part down, arguing that the studio ‘wanted to cut the money and put in a love interest’. One suspects that the idea of playing Field – the great character comic who was an alcoholic from the age of 13 – was too close to the bone for Hancock.

In 1949, just before he died, Field played Elwood P. Dowd in the London stage version of Mary Chase’s Pulitzer Prize winning play Harvey. The part of Dowd, an alcoholic whose best friend is an imaginary or invisible white rabbit, was immortalised by James Stewart in Henry Coster’s Harvey (1950) – and would be offered to Hancock in 1964. Again, Hancock, who had seen the film many times, turned the part down. He had followed and would follow in Field’s footsteps in various ways but, again, the idea of playing an alcoholic may have been too close to home for him.

Directed by Robert Day (fresh from Tarzan the Magnificent (1960) and The Grip of the Strangler (1958)) and produced by W.A. Whittaker [previously known for Ice Cold in Alex (1958) and The Dam Busters (1955)], The Rebel was the swansong of the Hancock/Galton/Simpson troika. It drew the safety curtain on one of the most productive partnerships in British radio and audiovisual history. Filming began at Elstree Studios in the summer of 1960 – with location shoots in Croydon, Dover, Waterloo, West Hampstead, Monaco, and Paris: the Champs-Élysées, Notre-Dame, Montmartre, Place de la Concorde, and Quais de la Seine. Hancock was a confirmed Francophile who periodically retreated to France at times of crisis, nominally to rest and recuperate, but, in fact, to continue a self-perpetuating, spiralling cycle of drinking and remorse.

He saw France as a refuge from his demanding work schedules and a source of cultural and intellectual stimulation. Additionally, as John Fisher says, ‘The idea of the French capital as a clichéd shorthand reference for a world of rebellion as represented by the artistic avant-garde was well known to him.’ Significantly, Hancock was also acutely aware of the magnetic pull Paris exerted on the American imagination. French cinema, literature and fashion were in vogue at the time. Albert Camus had popularised theories of the absurd and a bowdlerised, watered-down notion of Sartrean existentialism had filtered through even to the British public. We have no record of whether Hancock and/or Galton & Simpson named the film in honour of Camus, who had died in a car crash earlier in the year, but the wink to Camus’ The Rebel is surely a knowing one.

Hancock, Galton and Simpson were striving to make up for educations they’d missed. Autodidacts all, they may have lampooned their own thirst for knowledge and intellectual pretensions, in Half Hours like The Bedsitter, but they took ideas seriously. As Ray Galton says, ‘Because we met quite often socially, and discussed politics and philosophy and religion . . . we all felt basically the same about those things. I suppose we were all left-wing, non-believers as far as religion goes, and reasonably pessimistic about the human condition.’ Their discussions over drinks added bite to their humour and fed into the fun they had at their own, and Hancock’s expense in The Rebel.

It might be argued that the film’s fanciful plot is its principal failing. High jinks slapstick is all well and good, if you like that kind of thing, but the plot broke an essential link between Hancock and the lived experience of his audiences, unmooring his comedy from its essential anchor in the storm-tossed seas of reality. Like Hancock, Galton & Simpson were wrestling with a new medium, so it would be perverse to expect the perfection that comes with practise. The Winnipeg Free Press came close to the mark when it said, ‘If you sit down and analyse this film, you’ll probably decide it’s horrible rubbish. As pure golden foolishness, however, it ranks as a sort of miracle. A Hancock tour de force.’

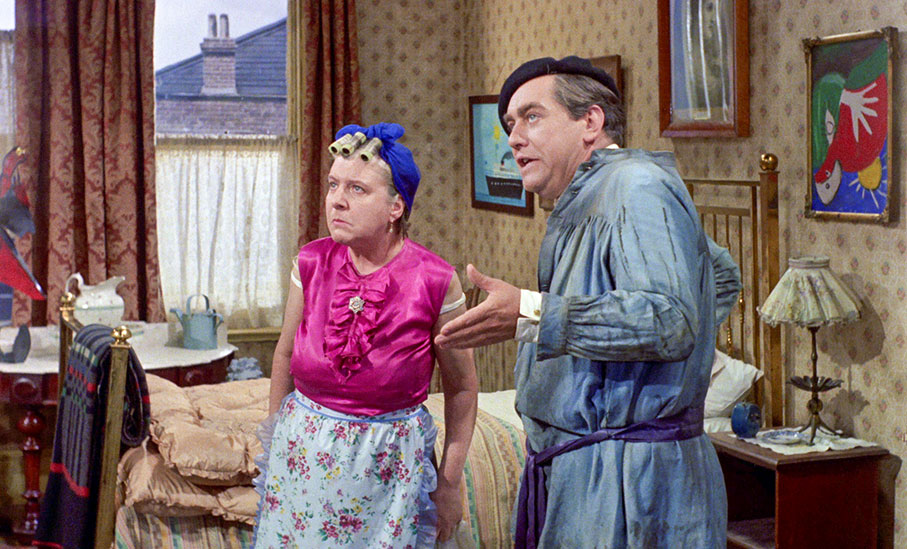

The Rebel revolves around Anthony Hancock, obviously, a bored and disillusioned petty clerk in a soulless bullshit job who dreads being trapped in mundanity and mediocrity until he’s eventually kissed off with a silver cigarette box. Hancock yearns for more and, although unblessed by talent, he daily rushes down ‘the drain’ before taking a train home to his West Hampstead flat to paint and sculpt. His landlady, Mrs Crevatte (Irene Handl) gives him notice after confronting the monstrous stone figure (‘Aphrodite at the Watering Hole’) he’s carving in his rooms and the jejune paintings on his walls while his patrician boss (John Le Mesurier) suggests a break after catching Hancock sketching his colleagues at work.

Clearly cracking up at the coalface of commerce, he decides to stake his all on his art and heads for Paris to make his name. Once there, he careers into a group of louche artists (including Oliver Reed) and befriends one (Paul Massie), a gifted compatriot who invites him to share his Montmartre studio. Hancock’s gauche blather and prattling about art win him admirers in avant-garde circles and diffident Paul, now convinced his own work is worthless, decides to pack it all in and return to England. He leaves his paintings behind for Hancock to do with as he pleases.

After word spreads about Hancock’s ‘genius’ spreads beyond the Left Bank, an art dealer, Sir George Brewer (George Sanders), visits Hancock at the studio. He instantly becomes besotted with Paul’s discarded work. Hancock tries in vain to explain that the favoured paintings are not his work and to persuade Sir Charles that his own infantile daubs are the real McCoy. Paul’s paintings sell well, and a London exhibition of new work is arranged. Caught in a trap, Hancock is next invited to Monaco to meet a shipping magnate (Grégoire Asian) aboard his yacht. The businessman’s German wife (Margit Saad) falls for Hancock, who is commissioned to produce a sculpture of her. Aphrodite makes her second appearance.

Increasingly desperate, Hancock contacts Paul, who is now lodging with Mrs Crevatte and working in an office, but who paints in his spare time. They rush Paul’s new paintings to the gallery in time for the private viewing, but Paul’s paintings turn out to be abstract imitations of Hancock’s old rubbish. When Hancock confesses that these are Paul’s paintings not his, Sir Charles, amused but undeterred, now caught in a trap of own, takes it all in his stride for money’s sake. Hancock leaves in disgust, shouting one of his Half Hour catchphrases at the startled company as he goes: ‘You’re all raving mad! None of you know what you’re looking at. You wait till I’m dead. You’ll see I was right.’

Galton & Simpson were at pains to deny they’d taken cheap shots at the soft target of modern art and its practitioners, but the film regrettably reflects many of the shallower elements of the contemporary discourse surrounding the avant-garde and the art world. Nevertheless, Lucien Freud, no less, considered it the greatest film about art he'd ever seen.

The Rebel had more going for it than Galton & Simpson’s kooky script and Hancock’s masterful comic acting. The film’s picture postcard Paris locations and the huge pulling power of its supporting cast added to its appeal. W.A. Whittaker deserves credit for raising the money that helped persuade some of the best seasoned actors of the day to work on the film. George Sanders was paid twice as much as Hancock for his supporting role in the film, but he could pack the stalls all on his own.

Perhaps best known to the British public for his role in The Saint film series, Sanders had already appeared opposite Olivier in Hitchcock’s Rebecca (1940), Bette Davis in Joseph L. Mankiewicz’s All About Eve (1950), and opposite Ingrid Bergman in Rossellini’s Journey to Italy (1954). The sartorially fastidious Sanders was more genuinely Bohemian than he appeared, certainly more so than the conformist cardboard-cut-out mock-Bohemians we meet in The Rebel.

Cliff Goodwin records that when Robert Day arranged a meeting between the ill-kempt Hancock and suave Sanders at Claridge's, the comedian was terrified: ‘The two men shook hands. “Hello, Tony,” says Sanders. “Hello, how are you?” replied Hancock. “Not too good, old boy,” confided Sanders, “I’ve got to the age where a good shit is better than a good fuck.”’ Goodwin also says that Sanders carried carpenter’s tools with him wherever he went and used them to ‘mend’ hotel doors and furniture if he felt they were askew or lop-sided. ‘I always do that when I’ve had a drink,’ he told Hancock, ‘It relaxes me.’ Perhaps that relaxed Hancock, perhaps it terrified him to meet someone more neurotic than himself.

Galton & Simpson tried their best to secure a cameo role for Sid James, but Hancock was having none of it. As far as he was concerned, he was heading to Hollywood glory and, as we have seen, was keen to ditch his East Cheam baggage. Happily, the delightfully idiosyncratic, irrepressible Irene Handl was offered the part of Hancock’s London landlady. Like Hancock, she came from a ‘comfortable’ middle class background but tended to play hard-pressed working class characters. Prior to her appearance in The Rebel, she was an early driving force behind the Lewisham branch of the Elvis Presley Fan Club. Soon after finishing the film, she published the first of her highly regarded novels, The Sioux (Longmans, 1965). Handl was a much-missed, remarkable woman.

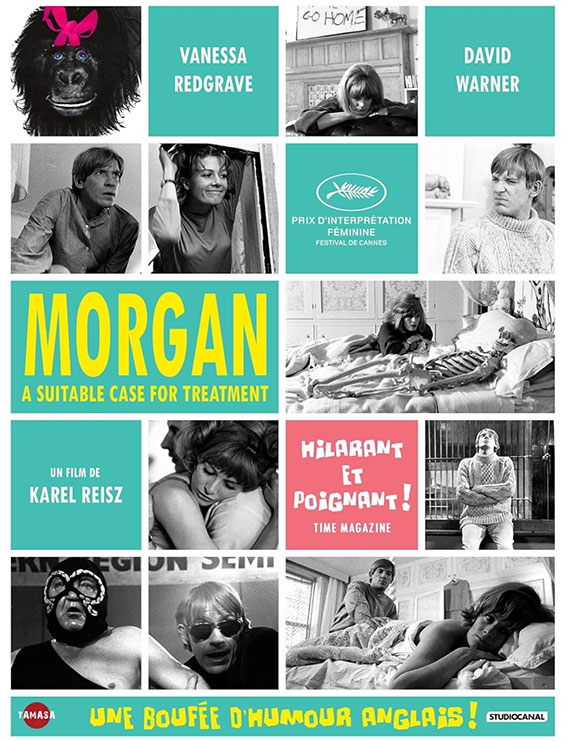

Always in work, always the bridesmaid, Handl appeared in a score of supporting roles in some terrible tripe (including her turns in the above-mentioned Carry on Constable, Doctor in Love and The Pure Hell of St Trinian’s). She also graced some of the most captivating British films of her day: Anthony Pelisier’s The History of Mr Polly (1949) Carol Reed’s A Kid for Two Farthings (1955), and Karl Reisz’s Morgan, An Unsuitable Case for Treatment (1966) – in which she utters a line that might’ve given Hancock pause for thought: ‘You know he wanted to shoot the Royal family, abolish marriage, and put everybody who'd been to public school in a chain gang. Yes, he was an idealist your dad was.’

Handl matches Hancock stride for stride in The Rebel. The imperishable scene in which landlady and lodger lock horns is not only one of the highlights of the film, but also provides wry comment on the chasm of misapprehension and suspicion that divide the public and abstract or conceptual art. When Mrs Crevatte criticises Hancock’s oil painting of ducks in flight, he replies, ‘Well, they fly at a fair lick, those ducks. They’re up, out of the water and away. You just have to whack on whatever you’ve got on your brush at the time.’ When Hancock explains that one of his paintings is a self-portrait, Mrs Crevatte replies, ‘Who of?’ When she returns later in the film, we are delighted to see her. When Aphrodite returns, less so.

Dennis Price is in there too, fresh from Pat Jackson’s What a Carve Up! (1961), but best known for his appearances in Powell & Pressburger’s A Canterbury Tale (1944 and Robert Hamer’s Kind Hearts and Coronets (1949). In The Rebel, Price plays Jim Smith, a moneyed artist who sleeps on top of his wardrobe, keeps a cow in his flat, and invites Hancock to an ‘existentialist’ party in his apartment. The Bohemians there all wear black. The women all look like Juliette Gréco. The men all sport Van Dyke goatee beards. Hancock tries to explain to them why he had to escape the rat race and London: ‘You’ve no idea how frustrating it is to work with people with imagination. They all looked alike. They all dressed alike’. Ah yes, the herd of independent minds. The point is well made, but the humour is, as it is at times throughout the film, hit and miss.

Mercifully, the Bohemians don’t wear berets, play bongo drums, and smoke dope, but, hey, they do appreciate and write bad poetry. So John Wood plays the gawky poet at the party who recites inept free verse – until Hancock gifts him his closing line: ‘washing me feet in a glass of beer’. The scene is an obvious echo of the 1959 Poetry Society episode of Hancock’s Half Hour in which Sid James babbles, ‘Mauve world, green me, Black him, purple her, Yellow us, pink you...’

Nanette Newman has a walk on part too, as Josey, who wears green lipstick, and says, ‘Why kill time when you can kill yourself?’ It’s one of those moments when the Half Hours or films chill to the bone by seeming to predict or foreshadow Hancock’s death. Another is the conversation he has, in The Rebel, with the reproduction of a Van Gogh self-portrait that hangs on the walls of his lodgings: ‘You went through it, didn’t you mate . . . Why do they persecute we great men?’ It’s funny but, given Van Gogh’s suicide by shotgun, it smarts.

If Galton & Simpson roll out the stereotypes, they also gift Hancock some great lines. He tells a Yogi leaning upside down against a wall the story of the man who, determined to prove the power of mind over matter, had himself chained up in a lead box and buried twelve feet below ground: ‘He had no food, no water, and no air – and he stayed like that for six weeks. When they finally dug him out, to everyone’s amazement he was stone dead. Of course, there were some sceptics who claimed it was all a trick and he was already dead when they put him down.’

Despite its great cast and some great writing, the film was bedevilled with difficulties from the outset. Hancock had come to feel, as so many did and do, that Hollywood was cinema’s Mecca and that the Dream Factory was a golden ticket to international recognition. If we read The Rebel as Hancock’s homage to Jacques Tati and The Punch and Judy Man as his encomium to Charlie Chaplin, we must add that both films were stubbornly and decidedly British. This may not have been an insurmountable obstacle to Stateside success; after all, if the Yanks could warm to Jimmy Porter and Arthur Seaton why not to Hancock?

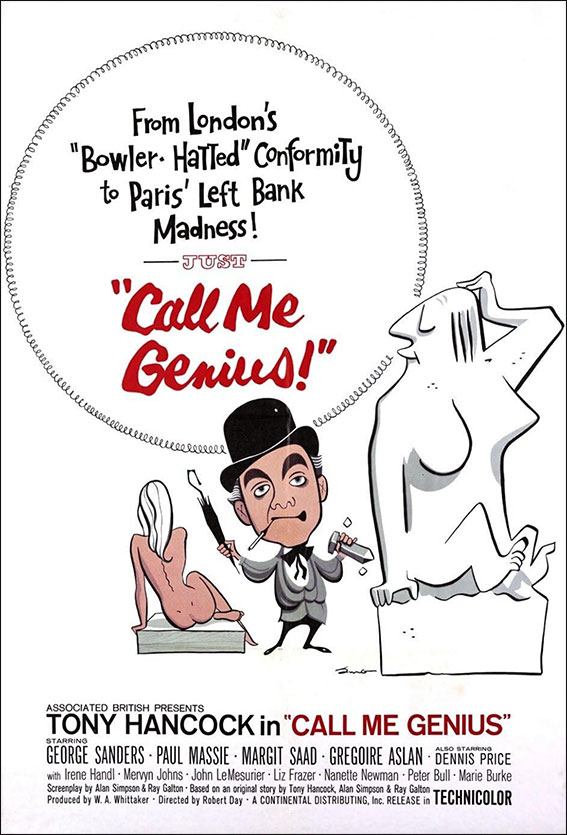

Any such possibility was soon scotched by a cruel quirk of fate: a U.S. TV series called The Rebel (1959-1961), about a former Confederate soldier in the Wild West, necessitated a change of title for Hancock’s film. The Rebel was released in the U.S.A. with the title Call Me Genius. It was a spectacular blunder. As Hancock says, ‘They weren’t used to me like the folks back home. Here, we’ve grown up together. The British public knew when I was taking the mickey and when I’m being serious. So, when I was boosted as the Big British Comic, they came to the cinema, folded their arms, and said, “Ok. Show us!”’ You can see their point. Even before the film’s première, then, North American hackles were well and truly up. Hancock was on a hiding to nothing in the States from Day One.

Cliff Goodwin helpfully describes the disaster of the film’s U.S. première: ‘Hancock arrived in New York to face the full fury of American hypocrisy; not only did the majority of East Coast critics dislike the film, branding it “too predictable, too slapstick . . . and too English”, they also took offence to the “pomposity of the title.” The fact that Hancock’s fame was founded on the pretensions of a bombastic fool went unnoticed.’ With his passport to Ho llywood effectively shredded, a part of Hancock gave up the ghost.

If the apparent arrogance of the idiotic titling of the U.S. release all but sunk the film in the States, two equally asinine decisions militated against its success on home soil. Firstly, to satisfy Hancock’s ambition to go global, it was decided to render The Rebel in international, for which read Americanised and homogenised language. Hancock had met Stan Laurel in the States and when Hancock asked the veteran comic for advice, he said, ‘Cut out the slang.’ Hancock returned to England and demanded that the self-same colloquial English that lent so much brio and zip to Hancock’s Half Hour should be excised from The Rebel.

‘I am aiming at a universal comedy,’ he said, ‘that will transcend class and state barriers.’ Hancock, who had powers of veto on the film, personally butchered the script, cutting out line after line of sparkling Galton & Simpson dialogue and whole coherent scenes, reasoning, reasonably in the event, that ‘they won’t understand that in America.’ There’s a paradox at play here that would repeat itself down decades: by attempting to reproduce an imaginary recipe for success in the States, British filmmakers and producers frequently sacrificed the very qualities that helped their films succeed. The universal is earthed in the local.

Hancock’s battered self-confidence was buttressed by the film’s huge success in Britain, where his popularity and the native love of laughter ensured it was a runaway commercial success. The critics had reservations, but the British flocked to see their beloved ‘Ancock in their droves. As John Fisher says, ‘The Rebel was one of the biggest British box office hits of the period: ‘It established a circuit record for Associated British Pictures Corporation (ABPC) and throughout the country, in many venues delivering a good week’s business in a single day.’ It also outperformed high earners such as the year’s two Carry on capers (Carry on Constable and Carry on Regardless), the latest instalments in two well-liked film series – Doctor in Love and The Hell of St Trinian’s, and Norman Wisdom’s commercial flop The Girl on a Boat.

The Rebel was as successful in Canada as it was in Britain, so Hancock somehow found the strength to carry on. His resilience was, anyway, stronger than his pained disappointment (at least at that stage of his life) and his desire to shine on film was dented but undimmed. Another choice that might have cost the film and its star dear was Robert Day’s decision to shoot in Technicolor. Hancock would later brush the dangers off by saying, ‘The Rebel had to be made in colour because of the paintings,’ but British and Canadian audiences used to seeing their hero in black and white on telly were suddenly severed from the familiar and from the Hancock they had come to know and love. In the event, again, no damage was done. Cinematographer Gilbert Taylor worked his magic, but Hancock’s next film, The Punch & Judy Man, would be as British as they come and be deliberately, defiantly shot in black and white.

I’ve not been able to find any specific information about the restoration undertaken of The Rebel for this StudioCanal Blu-ray release, but the results are spectacular enough to convince me that the original camera negative was used as the source. As Paul Merton states in the commentary track, this is the only colour record we have of Tony Hancock in his prime, and oh, what colour. The film was shot on Technicolor stock, and the colour on this 1080p transfer is consistently rich without oversaturation, and the brighter tones genuinely pop from the screen. Couple this with sublimely graded contrast and crisp image sharpness and detail, it looks almost as if the film was shot this year, though in some ways it’s better than that because it was shot on film rather than digital, and that really shows here. Framed in its original aspect ratio of 1.66:1, the transfer is also spotless, there is no whisper of movement within the gate, and a very fine film grain is visible.

The Linear PCM 2.0 mono soundtrack has some inevitable tonal restrictions, but is otherwise clear, and is clean of any evidence of wear or damage.

Optional English subtitles for the hearing impaired are available.

Commentary with comedian Paul Merton and screenwriters Ray Galton and Alan Simpson

Recorded, I’m guessing, for a previous DVD release (in the press notes for this disc, StudioCanal did not mark this inclusion as being new to this release), this commentary by comedian and Tony Hancock fan, Paul Merton, and the screenwriters of The Rebel and Hancock’s earlier TV and radio work, Ray Galton and Alan Simpson, is an enjoyable and informative one. Merton effectively acts as host by asking questions of Galton and Simpson, often about specific sequences as they play out but also about working with Hancock in general. There are some engaging and revealing stories here, including the news that the seemingly upper crust John Le Mesurier was an enthusiastic jazz fan and would hang out at Ronnie Scott’s jazz club until two in the morning; that Oliver Reed was nearly fired for repeatedly fluffing his brief speech but was kept on because of how magnetic his delivery was; that the film remains popular with artists and was described by Lucien Freud as the best film about the art world that he had seen; and that Hancock himself was far from the morose character he played on screen and was always great fun to work with. There’s a fascinating story about how producer W.A. Whittaker precured a stick of dynamite to create the bubbling water effect when Hancock’s statue falls into the dock, and I learned here that the paintings created by Alistair Grant for the Paul Ashby character were done in his own style, and that after his infantile art ones done for Hancock’s character were destroyed, they were recreated by the Pataphysical Society for an exhibition of artwork from the film. There’s plenty more of interest, though the information flow occasionally gets put on hold so that Merton can laugh at and praise his favourite gags and scenes.

An Irrepressible Streak: Paul Merton on The Rebel (16:58)

In one of two new special features on this disc, Paul Merton provides a brief biography of the journey that led Tony Hancock into comedy, and the partnering with writers Ray Galton and Alan Simpson that took him into radio, television, and the first of two films under review here. Merton is a huge fan of The Rebel, which he describes as a brilliant film and Galton and Simpson’s best screenplay by far, and has personal reasons for why he believes its subject matter is so relatable. There is some duplication of comments made in the commentary when it comes to George Sanders, but Merton also covers Hancock’s decline following a drunken car crash, and opines that his decision to part ways with Galton and Simpson after the final year of their TV show did him no favours. “I don’t think there’s a comedian who has been better served by writers,” he notes, “and he got rid of the two best writers he ever had.” He also cites Bosley Crowther’s scathing New York Times review of the film as indicative of why it failed to land with American audiences. “I think you probably just needed to understand a little bit about British culture to get what Tony was doing,” he suggests, then adds with a laugh, “And also, not be an idiot.”

A Definitive Comedian: Diane Morgan on Tony Hancock (12:15)

Actress and comedienne Diane Morgan recalls being first exposed to Hancock’s TV shows when her father brought tapes of them home and insisted that she watch them, with the result that she quickly became obsessed with this unique comedian’s work. This led to her hunting out the Hancock appreciation society and having to wait in line to see any new video snippet of the comedian that it uncovered. She recalls seeing The Rebel quite soon after first discovering Hancock’s work, and although she felt that he somehow didn’t look right in colour, she loved the film regardless and opines that that the best scenes are ones in which Hancock has someone to react against. She suggests that there was something so British about Hancock that he was probably never going to work in America, and she’s clearly not the biggest fan of the shift in his persona for The Punch and Judy Man, stating of this first break with his long-term writers, “I don’t think he realised how much Galton and Simpson enhanced his work.”

Behind the Scenes Stills Gallery (1:37)

A rolling gallery of 19 behind-the-scenes stills and publicity portraits, including portfolio shots of Nanette Newman and Oliver Reed. There are a couple of gems here, and in case you were wondering, the lines drawn on some of them are there to indicate the required framing for press releases.

Theatrical trailer (2:46)

Very much a trailer of its time but solidly assembled nonetheless. It’s a bit on the dark side, though.

Part 2: The Punch and Judy Man >

|