|

– Part 2: The Punch and Judy Man –

| |

'When we set a bewildered, divided man up in a blaze of publicity, turn him into a national figure, and give him thousands of pounds a week to play with, we subject his character to a terrible test. Hancock went to pieces. Yet that other destructive self, I feel, had better qualities and more real depth of feeling than TV ratings and showbiz will ever understand. And his half-hours on the little screen . . . are unique because they are droll shadow-shows of the tragicomedy behind them in his reality – and ours.' |

| |

J.B. Priestley, ‘Life Class’, The Sunday Times, 1969 |

| |

'I balanced all, brought all to mind/The years to come seemed waste of breath/A waste of breath the years behind/In balance with this life, this death.' |

| |

W.B. Yeats, An Irish Airman Forsees His Death |

Tony Hancock was a divided soul riddled with contradictions. An imperfect perfectionist, he possessed a childlike innocence and all too adult capacity for drunken violence. By turns absurd and noble, he was a melancholic Clown and serious-minded Fool, a philistine among intellectuals and a pseudo-intellectual among philistines, a control freak who squirmed when constrained, a disciplined performer who couldn’t learn his lines, a revolutionary comedian and cultural conservative, a Chaplin for the Welfare State and a Tati from East Cheam, an incurable romantic and a rampant misogynist, a beloved national treasure and chronic alcoholic, a family favourite and serial monogamist. In short, he was a complex, riven man who took his own life at the age of 44 but lives on what Dennis Norden called ‘an echo of remembered laughter’.

Hancock loved his audiences, but at times he loathed them. ‘I’ve been criticised quite a lot because I try to move on’, he said, ‘And the British public, though very loyal in many ways, are very resistant to change. But comedy is such a fascinating art that you cannot stay static and just collect the cheque.’ Hancock sought to expose his own idiocy, and that of the whole wide world, but the kickback was fierce.

In late 1961 and in the aftermath of Hancock’s last BBC success, the critic David Hill wrote in Contrast magazine that ‘Occasionally a TV series wins a kind of exemption from criticism. Once a programme is accepted as being one of the best, comment is confined to a verbal salute . . . The standard itself goes unquestioned. Tony Hancock is the only comedian to have earned himself this kind of critical dispensation.’ Fast forward a year: as filming began on The Punch and Judy Man the gloves were off, the dam had burst, and Hancock was considered fair game.

By the time of his second and final film, Hancock was in deep, deep trouble: he had sacked the writers who best understood the fine-hair connection between his baffling personality and the beloved character he played, his forlorn attempt to ‘crack the American market’ had failed miserably, the critics had begun to round on him, his drinking was out of control, and he was floundering in face of the irreparable damage done to his fragile self-confidence. He was one helluva mess.

| Hancock, Priestley and London End |

|

J.B. Priestley, one of Hancock’s most ardent, eloquent and perceptive admirers, had risen to prominence with his best-selling comic novel The Good Companions (Heinemann, 1931), which follows the fortunes of a travelling variety company. The droll Yorkshireman understood comedy, and Hancock better than most. In English Humour (Heinemann,1976), his wonderful survey of the comic traditions that Hancock was descended from, Priestley suggests that genuine humour – as opposed to the catchphrases, machine gun gags and funny voices that Hancock so despised – was timeless. He argued that three elements were essential to the great humourist: affection, a sense of irony, and some contact with reality. All three were present in The Punch and Judy Man.

In London End (Heinemann, 1968) the second part of his diptych The Image Men, Priestley draws a character, Lon Bracton, who is ‘indecisive, moody, probably quite neurotic’, and is unmistakably Tony Hancock. Bracton’s North American agent, Wilf Orange (!) says, ‘Look, half the time, no, say a third, he’s a wonderful hardworking comedian . . . the other two-thirds of the time, Lon’s beany, foofoo, nutty as a fruitcake. It’s not the sauce, the hard stuff, though he can lap it up. It isn’t even the women though there’s always one around, sometimes married to him, sometime not. It’s Lon himself. He’s several people. He goes to the can a good sweet guy, and comes back a lousy bastard . . . Yet when he’s really working and it’s all coming through, I tell you, this is a great comic – the best we’ve got’.

Orange consults Dr. Owen Tuby (!) to help straighten Bracton out. Tuby eventually delivers his diagnosis: ‘You’re a neurotic man who plays an even more neurotic man. Instead of trying to fight it, you go along with it . . . [but] if you watch your timing – and you know all about that, Lon – you can go on and do almost anything you like . . . You could eat your supper and read the evening paper on the stage and they’d still love it.’

Ray Galton and Alan Simpson

Priestley believed that the high peak of genuine comedy on TV ‘was reached by the sketches from Galton and Simpson for Tony Hancock, who seemed to me to combine an unconscious despair and hatred of show business with more than a touch of genius for it, finally giving him deep at heart a death wish.’ Easy to say with the benefit of hindsight, Jack, but it may be more accurate to say that Hancock’s mounting despair was so evident to the lad himself that he chased himself to the grave and that his attitude to showbusiness was commensurate with his standing within it.

Hancock regrouped after the critical mauling The Rebel had suffered across the pond, stubbornly sailed on, tacked back to shore, and sought a safe port in from his growing storm back in Blighty. In The Rebel, he had hoped to mediate between Europe and the U.S.A. and to achieve international stardom but been stretched beyond his limits. In The Punch and Judy Man, he is back on home soil and turns his attention to familiar settings and subjects: pubs, seaside towns creative failure, and marital turmoil. In 1961, Hancock had outlined his concept for the latter to Philip Oakes, the writer he chose to replace Galton & Simpson: ‘There’s this Punch and Judy man, a genuine artist in his way, with a marriage that’s going wrong, and a lot of bastards on the council out to nail him.’

Hancock’s devoted friend Sid James nails it, as he so often did, when he says, ‘Tony so wanted the film to be the best thing he’d ever done in his life, but he was falling apart then. He was drinking too much, he was coming late on set, he was trying to tell the director what to do.’ The director, Jeremy Summers, was a rooky nepo baby slogger while Hancock was a seasoned shining star of British entertainment, and the fallout from that power imbalance did untold damage to the film. It’s hard, if harsh, to see Summers as anything more than a naive ‘Yes’ man hired so that Hancock could exercise complete control over the film’s execution. Summer was technically competent, but he couldn’t handle Hancock. Few could.

Only two stills were published from the many Henri Cartier-Bresson took with his Leica after accepting an invitation to record the shoot – one of which graces the cover of Cliff Goodwin’s Hancock biography When the Wind Changed (featured above). Cartier-Bresson was to beat a hasty retreat from the project, saying, ‘Each day was an agony, for me as a photographer and for Hancock as a comedy actor. He adds, cryptically, ‘What I saw was not the Hancock that the world loved.’ Whether he was alluding to aspects of Hancock’s behaviour he’d not been warned about (the incipient alcoholism, the ingrained misogyny, the megalomaniacal bullying) or simply knew more about Hancock’s Half Hour than seems likely, he echoed sentiments devotees of Hancock’s earlier work would share.

In the Sunday Times article quoted from above, J. B. Priestley says, ‘By some mischance, I missed his film The Punch and Judy Man, his very own creation, as if he might be another Chaplin. So, I cannot help wondering if there might not be more in this film than the immediate disappointment suggested – if now, years afterward, something original and rewarding might not be rescued out of it.’ Happily, posterity has been kinder to the film than most contemporary audiences and critics were. It is one of those minor classics from the past that improve with age.

The film is as full of flaws as The Rebel had been and as Hancock was, and the humour is once more hit and miss, but The Punch and Judy Man stands tall now as a bittersweet and piquant portrait of a largely vanished world – that of salubrious mass holidays in breezy seaside towns already grubby with neglect even before foreign travel came within the reach of all; in the days of cosy-tawdry B&Bs and caffs offering a ‘Full English Breakfast’; the days of candyfloss, deckchairs, donkey rides, ice-cream parlours, ‘the illuminations’, white knotted-handkerchiefs, candy pebbles in glass jars, postcards home, piers pounded by grey seas, castles in the sand, sand in bags of chips, and Punch and Judy shows.

The largely vanished world, too, of segregated public houses, public-spirited stale pale males debating funding for civic improvements in gilded council chambers, daytrip charabanc beanos, wakes weeks, and hard-working folk happy simply to stroll with others like themselves and gulp in fresh air on wind-buffeted beaches, esplanades and promenades. As he did in Technicolor in The Rebel and does here in splendent black-and-white, Director of Photography Gilbert Taylor brings finesse and freshness even to the grim, rain-lashed setting of Bognor Regis early in the season.

In his autobiography, A Jobbing Actor (Elm Tree Books, 1984) Hancock’s close friend John Le Mesurier recalled, ‘The trippers had stayed away in swarms that year and the few brave regulars who could not bear to break a habit of a lifetime, sat about in sad, usually damp little groups reflecting on the irony of paying for a holiday that was best calculated to bring on a fit of depression.’ Various other factors besides the film’s sombre setting cast a pall over proceedings. Le Mesurier – whose first wife, Hattie Jacques, makes a brief appearance in the film and whose second wife, Joan, would soon be involved in a destructive affair with Hancock – was a steadying influence on Hancock throughout, but only up to a point.

Le Mesurier couldn’t much calm his friend when it became clear to all involved in the film that the veteran puppeteer and Punch professor Joe Hastings, a diminutive chain-smoking crew member, was dying of lung cancer. Hastings had tutored Hancock in puppetry (as Hancock had tutored the puppet Archie). He taught Hancock how to use a ‘swozzle’, and worked the puppets when he was otherwise engaged. He died soon after the film was finished, as did Walter Hudd, an extra on the film. It all felt like a bad omen to Hancock, and he may have been right.

Hancock was a firm believer in diets (his favoured one involved dispensing with food altogether and surviving on spirits alone), but he didn’t believe in deities. If he had done, he could have been forgiven for thinking the gods were against him. If he took a rational view of religion, he was, nonetheless, a mess of irrational neuroses, phobias and superstitions. We’ll come to his irrational perfectionism soon, but first a word about the irrational hostility to puppets he had acquired as a boy in Bournemouth. He hated the one he had tutored in Entertaining Archie, he especially hated the crocodile puppet in The Punch and Judy Man, and he became genuinely convinced that Mr Punch had it in for him and the whole project: ‘The film’s jinxed. He won’t let it go right!’ Which only goes to prove that his ferocious drinking was damaging his mind.

While the hooch was frying Hancock’s brain, it was also fraying his first marriage, to Cecily, a relationship writ large in the marriage at the heart of the film. Hancock was acutely aware of the correspondence, but it must be stressed that their marriage never descended into the spectacular violence of a Punch and Judy show. The same cannot be said of Hancock’s second marriage, to his press agent Freddie Ross, or of his later relationship with John Le Mesurier’s wife, Joan.

The three women tried everything they could to keep their beloved Hancock sober, but all their efforts were in vain. Often, the brutal violence he meted out arose when they tried to remove his bottles of vodka or brandy. As J.B. Priestley says in ‘Life Class’, ‘He could be Tony Jekyll in the afternoon and Hyde Hancock at night’. Before we rush to coin futile platitudes and indignantly drop Hancock into the dustbin of history, all that can usefully be said of his despicable and indefensible violence is that the treatment of alcoholism was comparatively primitive in Hancock’s day, that addiction and mental health crises were not comprehensively comprehended or sympathetically treated then, that domestic violence was shamefully swept under the carpet too, and that the dark impulses that lurk in the human psyche cannot be productively resolved here.

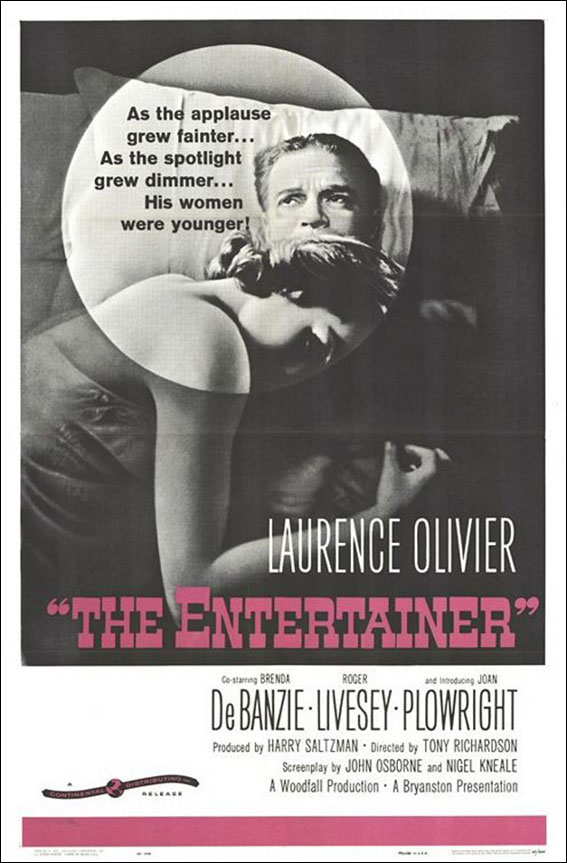

It is striking that, while Hancock perceived the parallels between the marriage in the film and his own analogous marriage, he didn’t appear to see the parallels between himself and Wally, the puppeteer in the film – another floundering entertainer in a foundering marriage and an uncertain future. Nor did he did he see those between himself and Laurence Olivier’s Archie Rice in Tony Richardson’s The Entertainer (1960) – a washed-out performer struggling to survive in the dying days of music hall. Perhaps he saw such things only too well, and blanked them out with booze. At any rate, the part of a man with his hand up a Punch puppet was a really strange choice of role for a man with such an aversion, one who staked his all on the role to prove that he was fine really and that his film career wasn’t, most definitely wasn’t stalling.

Audiences who’d earlier seen The Entertainer must have found The Punch and Judy Man imitative or, at the least, eerily familiar. In both films we meet fading seaside entertainers (Rice/Pinner) in fading locations (Morecambe/Bognor Regis) and fading cultures (music hall, beach entertainment). In a perceptive Sight & Sound review of Richardson’s film that sits opposite a review of The Apartment, Penelope Houston talks of Archie as a man who’d chosen ‘failure on his own terms rather than security on someone else’s,’ who ‘has lived for a long time with defeat,’ so that ‘underlying everything he says is the sense of decay and despair.’ Houston might be talking about Wally Pinner and Hancock.

Houston concludes her review of The Entertainer by saying that Archie is ‘a man performing in life, condemned to live with the sham identity he has created. The other players . . . share the same qualities of likeableness and seriousness, energy and a kind of unshowy honesty. This kind of acting is something encouragingly new on the British screen; and cinema cannot be allowed to imagine it can continue to do without it.’ Hancock can only have been disappointed that his own equally honest performance in The Punch and Judy Man wasn’t similarly honoured or that he wasn’t blessed to be reviewed by one as astute as Houston.

The film revolves around the strained marriage of Punch and Judy man Wally Pinner (Hancock) and his socially obeisant wife Delia (Sylvia Syms). Wally, like the Hancock of the Half Hours, is a free spirit down on his luck and at odds with authority – in this instance, represented by the local Mayor (Arthur Palmer) and Borough Council. While plying his trade on the windswept beaches of the dismal seaside resort of Piltdown, he struggles to make ends meet among the demi-monde, while Delia keeps the show on the road by running the knick-knacks shop they live above.

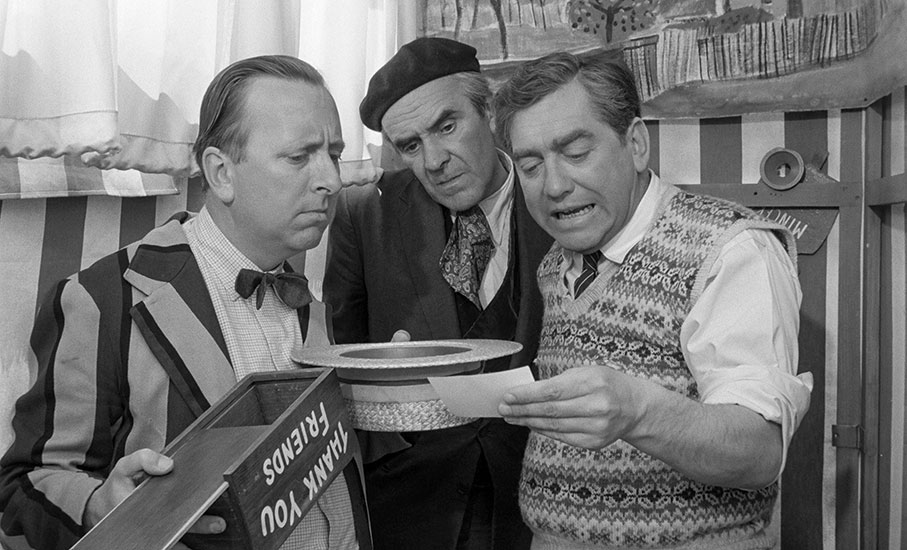

In his scrimmages with the council, Wally makes common cause with his fellow drifters: his ‘Judy’ sidekick Ed Cox (Hugh Lloyd), Sandman Charles Ford (John Le Mesurier) and opportunistic snappy snapper Neville Shanks (Mario Fabrizio). Along the way Wally befriends a stranded waif (Neville Webb) and treats him to a knickerbocker glory. Delia yearns to be accepted in the very High Society circles Wally despises and will do anything to advance. The Lady Mayoress, Mrs Palmer (Pauline Jameson), persuades her to sign Wally up for a performance at the Gala Dinner being arranged to celebrate Piltdown’s diamond jubilee. Wally is initially appalled by the idea, but bends to pressure from Delia and Charles Ford, hoping to keep the peace, perhaps even save his marriage and ‘career’.

A celebrity toff, Lady Jane Caterham (Barbara Murray), and her braying escorts (Brian Bedford and Peter Myers) have been invited to the dinner as guests of honour by the obsequious Mayor. As her ladyship delivers her pre-prepared speech and switches on the illuminations, Wally is preparing for his show and his electric shaver fuses the lights. The banquet is also a fiasco: a bun fight is started by Caterham’s escorts and Charles, Delia’s chaperone for the evening, decks a boorish drunken guest. Wally’s booth topples over in the general fracas, blocking the route of escape of the disgusted Lady Jane. When she reaches for a soda syphon and takes aim at Wally, Delia intervenes to protect him. After receiving an ineffectual slap from the furious aristo, Delia replies with a neat right hook to the Caterham jaw. Neville’s photo of the punch makes the morning papers and, with Delia’s social aspirations wrecked, the seemingly reconciled Pinners agree to cut their losses and move on to another town.

In his review of David Bellos’s Jacques Tati: His Life and Art (Harvill Press, 1999) in the London Review of Books, Jonathan Coe says: ‘Audiences in the old Northern variety halls were notoriously unforgiving. “I suppose he’s all right,” a departing punter is supposed to have said of one hapless comedian, “if you like laughing.”’ Coe’s novel What a Carve Up! (Penguin, 1994) is a comic masterpiece Hancock himself might have written – if he could write. Coe understands humour well enough to perceive that the Northern punter’s subtle joke, while seeming to mock the rain-drenched miserabilist culture that produced it, rests on the assumption that laughter is universal; ergo ‘no one seems to be more important to a nation than its most famous and beloved clowns.’ And, we might add, no one seems to pay a higher price for the obligations that imposed.

David Bellos argues that in Playtime the Frenchman revealed himself to be, ‘not a reactionary critic of modern life, but a sentimental celebrant of its potential for beauty and joy.’ He adds that, ‘Tati was not out to change the world, but to help us look at it with less horror.’ The same or similar could certainly be said of Tony Hancock. In The Punch and Judy Man, Hancock once again doffs his cap to Tati, but the golden glow of Charlie Chaplin shines a greater light on the film. The Kid, Chaplin’s silent classic of 1921, about the relationship between a tramp and the abandoned boy he adopts and befriends, had left a lasting impression on Hancock, most obviously due to the mesmerising performances of Chaplin and Jackie Coogan, who plays ‘the kid 'imself’.

Hancock was in good company in his admiration for Chaplin’s film. The Chicago Herald and Examiner was especially effusive: ‘The Kid settles once and for all the question as to who the greatest theatrical artist in the world is. Chaplin does some of the finest, most delicately shaded acting you ever saw anywhere … The picture is perfection. Six reels that seem like one; six reels that are funnier than the work of any other human being; six reels that are sadder and simpler than anything in pictures; six reels that will atone for anything the movies have ever done.’

Aesthetics aside, there were more profound reasons The Kid resonated with Hancock. The autobiographical elements of The Punch and Judy Man are as plain as day. While Chaplin’s childhood in Elephant & Castle was famously grim, Hancock’s in Bournemouth was a largely happy one. As we’ve seen though, he was effectively abandoned by his parents: his mother was forever busy with the incessant demands of running a series of hotels (The Railway Hotel, The Durlston Court Hotel, The Harbour Heights Hotel, etc) while his father, a bon viveur and aspiring amateur comedian, tended to be otherwise engaged too.

Working with his new scriptwriter, Philip Oakes, who by a happy coincidence lived near Hancock’s Lingfield home, Hancock delved into his subconscious, hoping to repair the damage of that childhood neglect. And here, for once, fate dealt Hancock a good hand. Shooting for The Punch and Judy Man would begin in the Spring of 1962, but Hancock had first to hurdle flailing auditions for the part of Peter (the kid he befriends in the film). When the auditions faltered, Sylvia Syms suggested her nephew Nicholas, took him along to Elstree Studios, and introduced him to Hancock. The unphased, slightly cocky lad said, ‘Well, I don’t know Aunty Sylv, he didn’t make me laugh.’ Hancock overheard and made his mind up on the spot. He’s found his boy. Nicholas instantly became Peter, and, unknowingly, Hancock’s alter ego. By a happy coincidence, the seven-year-old lad was the spitting image of Hancock himself at that age, and, as is evident from their scenes together, the two clicked immediately.

The genuine Hancock-Webb friendship, which mirrors both the Wally-Peter one in The Punch and Judy Man and the Chaplin-Coogan one in The Kid, provides one of the film’s most convincing moments. When Wally is caught in a downpour, he spots the sodden boy cowering in a promenade shelter and tries to help him. Peter is wary at first, but Wally’s sincerity and humour wins his trust and, as the pair prepare to leave the shelter, Peter shyly takes Wally’s hand. It is tender and touching.

| The Search for Perfection |

|

Another scene involving Wally and the boy isn’t quite so successful, though through no fault on Nicholas Webb's part. Wally and Peter visit an ice cream parlour after Wally offers to buy the boy a treat. They order rich, creamy, mountainous ‘Piltdown Glories’ from the parlour’s proud owner (Eddie Byrne). An unusual duel or face-off ensues as the two adults size each other up, each knowing that Wally neither likes ice cream nor even knows this particular spécialité de la maison. Wally matches his more expert companion stride for stride, spoon for spoon, until, finally, he proves himself Peter’s equal by triumphantly tossing a cherry in the air and catching it in his mouth. Peter emits a heartfelt, respectful ‘That’s the way to do it'. Wally is cock-a-hoop at his success. The parlour’s owner is crestfallen and inwardly livid.

The ice cream parlour scene, Hancock’s own favourite from the film, tells another, darker tale: Hancock, initially a social drinker, was by now drinking around the clock; he hated ice cream and washed each detested mouthful down – with vodka. In that scene we see beads of sweat on Hancock’s brow that appear to be related to his reaction to the ice cream. With the benefit of hindsight, we may think otherwise.

The scene is deliciously funny, but it stumbles, because it is way, way too long. It had been written to last just over a minute, but Hancock insisted on working and reworking it until it ran to over eight minutes. Obsessed by now with achieving the kind of perfection painstakingly achieved by Chaplin, Hancock failed to see that he was at his best in spontaneous first takes. He was a myope where his urge to emulate his idols was concerned. We’re left wondering what might have happened had a proposed adaptation of Ionesco’s Rhinoceros in which Hancock was to star had come to fruition and he’d work with the prospective director, Alexander ‘Sandy’ Mackendrick – another perfectionist.

In his pean to Sylvia Plath and survey of suicide The Savage God (Wiedenfeld & Nicholson, 1971), Al Alvarez says that there’s a kind of suicide that ‘is simply a form of self-harm: ‘. . . a man may destroy himself not because he wants to die but because there is a single aspect of himself which he cannot tolerate. A suicide of this order is a perfectionist’. Certainly, but the increase in uneasy freedom attendant upon the growth of secular humanism and Hancock’s unrelenting search for meaning in life pose the question contained in an eerie note left behind in an empty house in Hampstead, ‘Why suicide? Why not?’

The Freudian psychoanalyst Karl Menninger says that there are three components to suicide: the wish to kill, the wish to be killed, and the wish to die. We mentioned Albert Camus above in relation to his novel The Rebel and Hancock’s The Rebel. Camus has things to say that bear on The Punch and Judy Man too. In The Savage God, Al Alvarez quotes Mersault, the hero of Camus’ L’Étranger/The Outsider (Gallimard, 1942): ‘I am bound to express my unbelief . . . No higher idea than that there is no god exists for me . . . All man did was invent god so as to live without killing himself. That’s the essence of universal history till now.’ Too little attention has been paid to Hancock’s atheism or agnosticism. It shaped his distinctly melancholic humour, helps explain his despair, and was among the many reasons he ended his life. As the power of religion weakened, in Hancock’s day, the pull of suicide increased; Hancock the non-believer had no metaphysical crutch to lean on, no heavenly way out.

We’ve now tumbled into the trap of emphasis on Hancock’s death rather than life, so, moving swiftly on, a final word on the film. The compelling scene in which Wally and Charles Ford take refuge in the latter’s beach hut is another one that leaps out from the uneven whole. The two men bat wry comments about life and the Gala Dinner back and forth over a cup of tea. Wally envies Charles for what he sees as his freedom from the chains of matrimony, but Charles disabuses him. Hancock and Le Mesurier were fast friends which goes some way to explaining the relaxed, completely natural flow of the scene. They were both perceived as great eyebrow actors and they waggle their way through this gently affecting vignette with expert ease. Like Hancock and Sid James, the two made a great double act, a comic marriage made in heaven, and it is a crying shame they were never offered a film, radio or TV series together.

The part of Wally’s wife was initially earmarked for the mighty Billy Whitelaw, later Samuel Beckett’s muse, but she was otherwise engaged. Whitelaw had already earned herself a Best Actress BAFTA award in 1961, and we have only to see her in The Comedy Man (1964) – another film about a down-at-heel struggling performer – to feel certain she would have added depth to The Punch and Judy Man.

No disrespect to Sylvia Syms is implied in that comment. Syms had already proved herself in Ice Cold in Alex (1958) – again under the watchful gaze of cinematographer Gilbert Scott. By an odd, wee quirk of history, Syms lived in an adjoining street, in Eltham, to the home of Hancock’s friend and BBC producer Dennis Main Wilson –just a few hundred yards away from Frankie Howerd’s childhood home, which was itself near to the birthplaces of Bob Hope and Steve Peregrine Took. Howerd and Took attended the same school. Make of that what you will.

If we owe Syms our thanks for bringing Nicholas Webb to the film, we owe her a still greater debt of gratitude for her brilliant and absolutely vital performance as Delia Pinner. In certain scenes, Syms carries Hancock, whose relentless on-and-off-set drinking left his previously malleable face, one of the essential tools of his trade, frozen stiff. While Hancock wasn’t as wilfully self-destructive as is commonly suggested by myth, he had certainly destroyed what John Fisher neatly calls, ‘the unique vocabulary of looks at his disposal.’ It’s as if the great Chilean folk hero and guitarist Victor Jara had broken his own agile and rebellious fingers in the National Stadium, Santiago in 1973 rather than had them broken for him by the incipient Pinochet junta.

Syms is especially superb in the scenes tense with loud silences in which the Pinners assault each other with cruel polished politeness. ‘Happiness is a china shop’, said the humourist H.L. Menken, ‘and love is the bull.’ Menken is a useful guide to Hancock’s divided self too, because he also said, ‘an idealist is one who, on noticing that a rose smells better than a cabbage, concludes that it makes a better soup,’ while a cynic is ‘one who, when he smells flowers, looks around for a coffin.’ Hancock was both an upbeat idealist and a riven cynic. His own mortal contradictions, exacerbated by industrial quantities of intoxicants, tore him apart.

Those contradictions, that drive for perfection, the unwitting parental neglect of his boyhood, the early loss of his father and of his brother during the war, the fear of flying embedded early on in front of unforgiving audiences on the variety circuit, his hatred of his body shape (those feet, that girth), the expectations of an adoring but conservative public, the vexing and destructive pressures of celebrity, the suicides of his step-father and Mario Fabrizi, the splits with Sid James and Galton & Simpson, his two divorces and violent final fling with his best friend’s wife, the loneliness and introspection, his rumoured and conflicted bi-sexual appetites, the guilt and remorse, the unsatisfied thirst for cultural and intellectual improvement, his melancholia and depression, his phobias and superstations, the Stateside mauling of The Rebel, the mixed reviews for The Punch and Judy Man, the nagging and self-fulfilling feeling his best days were behind him, the failure of his Australian ‘come-back’ tour’, his lack of belief in an afterlife and forgiving god – we cannot know what drew Hancock on toward that moment in the suburbs of Sydney in 1968.

Does it advance our understanding to know that Hancock’s final shambolic appearance on stage in England, at Festival Hall, was received with rapturous applause, recorded by the BBC, and snidely promoted in the Radio Times as follows: ‘Disaster has always been a strong feature of the comedy style of Tony Hancock. Social disgrace, penury, damage to person and property, violent abuse – all are familiar props. Of late, Hancock’s life has shown a distressing tendency to imitate his art.’

Does it help to know that he was subjected to catcalls at the Dendy Cinema in Melbourne when he fell over legless several times during a show, toppled into the auditorium at one point, and had to clamber back on stage on all fours? Or that he later repeated the show, free of charge, for all who’d attended the disastrous earlier one? Or that he may or may not have made sexual advances to Matt Monroe on a sleeper train during a tour? Or that he’d wander London’s West End for days, toward the end, dishevelled, stinking of urine, even excrement? The hideous details of his fall from grace and implosion tell us simply that he was losing his grip on sanity while his yellowing eyes and jaundiced pallor told their own tale.

Hancock with his second wife Freddie Ross and his mother at a football

match watching Bournemouth F.C. (credit: Bournemouth Daily Echo)

Hancock’s failed first marriage to Lanvin model Cecily Romanis led to her death. His failed second marriage, to his agent Freddie Ross, led inexorably to his failed violent affair with Joan Le Mesurier. In the opening scene of the last episode of Hancock’s Half Hour Galton & Simpson wrote, The Succession – Son and Heir, Hancock says: ‘What have you achieved? What have you achieved? . . . You lost your chance, me old son. You’ve contributed nothing to this life. A waste of time your being here at all. No plaque for you in Westminster Abbey. The best you can expect is a few daffodils in a jam-jar, a rough-hewn stone bearing the legend, “He came and he went,” and in between? Nothing! . . . Nobody will know I existed. Nothing to leave behind me. Nothing to pass on. Nobody to mourn me.’

It may have sounded funny at the time, but it’s another of those early mystical prophetic moments that chill us to the marrow. So, what did Tony Hancock achieve in his short life? Only the complete transformation of contemporary British comedy, the near single-handed invention of situation comedy, the creation of radio and television masterpieces that earned him fame and fortune, and two minor film classics that float a message in a bottle from his time to ours.

What did he leave behind and who mourned his passing? Only some of the funniest and most subtly moving comedy ever created by anyone anywhere, an echo of remembered laughter that reverberates still, the memory of his translucent eyes and bushy eyebrows, and, perhaps most importantly of all, the undying love of those who knew him and millions more besides. He was mourned by everyone from butcher to the candlestick maker, The Beatles to The Kinks, my dad to my best mate’s dad. When asked in 1966, what he’d do if he were offered recognition in the monarch’s honours list, he said, ‘Refuse it. I don’t want to be rewarded. I’m a practising comedian. I’m in it and I love it. I want to make people laugh, and as long as that happens, that’s enough reward.’ Tony Hancock – Our own beloved clown – Gone but not forgotten.

Given that The Rebel was shot in glorious Technicolor and The Punch and Judy Man was made two years later, it might seem surprising that the latter film was shot in black-and-white. Whether this was a budgetary decision (it was certainly more expensive to shoot on colour stock at this time), the result of Hancock being more comfortable with the monochrome look from his TV shows, or a deliberate attempt to align the film with the realist dramas of the Free Cinema movement is uncertain. Either way, the restoration and transfer on this StudioCanal Blu-ray is every bit as impressive as the one on the simultaneously released The Rebel. The 1.66:1 image is again sharp and the fine detail clearly defined, and the contrast has been impeccably graded, nailing the black levels and white highlights and displaying a wide tonal range between. The image sits solidly in frame, dust spots have been eliminated, there are no traces of damage or wear, and a fine grain is evident. Superb.

Once again, the Linear PCM 2.0 mono soundtrack is in fine shape, with the expected restrictions in tonal range not impacting on the clarity and robustness of the dialogue or music.

Optional English subtitles for the hearing impaired are again available.

Hard Knocks: Paul Merton on The Punch and Judy Man (10:26)

Paul Merton returns to talk about The Punch and Judy Man, and states up front that he believes it’s a good film but that it shouldn’t be seen as a comedy, being instead a bitter and caustic portrait of a marriage, and a critique of working class people who pander to the wealthy elite. He recalls seeing the film in the cinema as a kid and his mother’s negative reaction to a moment of perceived vulgarity that jarred with the Hancock persona that she and so many others were such a fan of. He does suggest, however, that the film is a valuable social record of life in a British seaside town in the 1960s, and that it acts as a showcase for Hancock’s skills as a dramatic actor.

Excerpt from ABC Series Hancock's (24:41)

The excerpt indicated by the title of this extra is actually the whole of episode 2 of the series Hancock’s that Tony Hancock made for ABC television in 1967, which was originally broadcast on 23 June of that year. Now, when I say the whole episode, that’s only partially correct, as while all of its audio is here, the only surviving video from the series consists of the final two minutes of this particular show. It thus plays out primarily as an audio track illustrated with photos of Hancock, presumably from this period, only switching to a low band video recording at the very end. The story of the episode revolves around an American filmmaker (played by Kenneth J. Warren) who is in town to make a documentary about swinging London, for which the eager Tony stages a fashion show whose comical costumes have the studio audience laughing but remain unseen to us. For me, this is some way from Hancock in his prime, with the programme having a variety show vibe that involves pausing the story twice for Carmen McRae to sing musical numbers, although Hancock’s occasional, seemingly improvised interactions with the studio audience indicate that he hadn’t lost his edge. What surprises in retrospect is not that the cultural references have dated (the long-haired man mistaken for a girl was a weary establishment favourite of the day), but the fact that Hancock openly refers to reefers and purple heart amphetamines. There’s also an in-joke when the American director tries to sideline him in favour of fashion model Esmerelda (June Whitfield), and he responds by pleading, “I can do an excerpt from The Blood Donor if you like.”

BEHP Audio interview extract with Jeremy Summers (6:14)

A short audio extract from the British Entertainment History Project interview with director Jeremy Summers in which he recalls being asked to meet Tony Hancock for breakfast (at which he drank coffee and Tony had a large vodka) and being hired to direct The Punch and Judy Man as a result. He remembers thinking that the screenplay by Hancock and Phillip Oakes was rather dry, and notes the concern that he and producer Gordon Scott had a week into filming about how the film was shaping up prompted them to approach Tony and ask him if he was sure this was what he wanted to do. He admits to seeing what Hancock was trying to do, but suggests that the public just didn’t want to see the comedian playing Hamlet.

Blackpool Show: Season 1 Episode 7 (1966) (53:25)

Episode 7 of a weekly TV variety show held at the ABC Theatre in Blackpool, the final one to be hosted by Tony Hancock before handing over to Bruce Forsyth. I’ll hold my hand up here and admit to disliking variety shows, but as a time capsule of talent of the day this is still of real interest for the more tolerant viewer. Hancock himself is certainly on decent form, particularly when teamed briefly with favourite comedy foil John Junkin, but I winced my way through two acts that were the bane of my younger days – annoying stand-up comedian Freddie ‘Parrot Face’ Davis, and The Rockin’ Berries, a mediocre pop group with a member whose sole function was to perform a series of half-arsed impersonations of familiar targets, including Tommy Cooper, Eric Morecambe and Norman Wisdom. We get three musical numbers from singer Jeannie Carson, and a long and irritating riff on Goldfinger from a young Bob Monkhouse, who nonetheless also delivers a banger of a gag about the so-called typical Englishman, one that still feels highly relevant today.

Behind the Scenes Stills Gallery (1:42)

A rolling gallery consisting of monochrome behind-the-scenes shots and a single posed publicity photo, all of impeccable quality, some with those scribbled marks to indicate the desired framing for press releases. Again, there are some really nice shots in here, my favourite being one of Hancock laughing uproariously in the company of director Jeremy Summers and the his good friend and colleague, John Le Mesurier.

Theatrical Trailer (2:50)

A lively trailer that deceptively promotes the film as a fast-paced wacky comedy.

< Part 1: The Rebel

|