|

In the first of a few unusual narrative strategies for the time, we begin with a pre-credits sequence. Wellington bomber B for Bertie is over the Netherlands, after one of its engines has been damaged during a bombing raid on Stuttgart. No one is on board as the plane flies on. Finally, B for Bertie crashes.

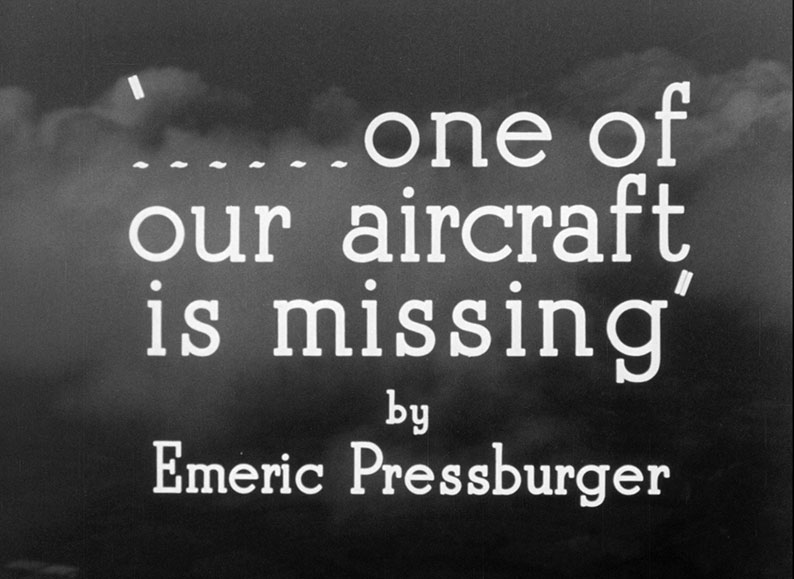

Then, the opening credits and title. To get a pedantic filmographic note out of the way, this film’s title is usually rendered as One of Our Aircraft is Missing, and for the sake of convenience that’s how I’ll refer to it. However, on screen it is actually called:

The opening credits go on to introduce each of the bomber crew of six visually: John Glyn Haggard, pilot (Hugh Burden), Tom Earnshaw, co-pilot (Eric Portman), Frank Shelley, navigator (Hugh Williams), Bob Ashley, wireless operator (Emrys Jones), Geoff Hickman, front gunner (Bernard Miles) and George Corbett, rear gunner (Godfrey Tearle). We then flash back fifteen hours to the start of the mission, and see why in the missing bomber the crew were missing: they bailed out close to the Zuider Zee. Five of the six find each other straight away. The narrative of the film are the efforts to get the airmen out of the country and back to England, with the help of Dutch locals, especially English-speaking school teacher Els Meertens (Pamela Brown), burgomaster’s daughter Jet van Dieren (Joyce Redman) and resistance leader Jo de Vries (Googie Withers).

Michael Powell had first worked with Emeric Pressburger three years earlier with The Spy in Black, on which the latter did some rewrites. They worked together on Contraband (1940) and 49th Parallel (1941). With these films, the credits indicated a division of labour: Powell was the director, Pressburger the writer (though Powell gets a scenario credit on Contraband). In that capacity, Pressburger won an Oscar for 49th Parallel. However, One of Our Aircraft is Missing immediately signalled a change. You can see above that Pressburger received a proprietary credit but the opening titles end with: “Written Produced and Directed for The Archers by Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger”. We don’t get the future logo of an arrow thumping into its target, but the great partnership is now in place, and the name of their production company.

As I mention above, Powell and Pressburger make a few unusual choices for a film of its time. Not only is there a pre-opening-credits sequence, there’s also one after the end credits. There is no music score, other than part of the Dutch national anthem played over the Netherlands coat of arms at the very end. Powell and Pressburger strove for naturalism for this film, and to that end the Dutch and German characters speak Dutch and German on screen, not forgetting a small amount of Latin in a church service. Multilingual films were not common in Britain or the US at the time, with foreign characters generally speaking English, with The Longest Day (1962) being a groundbreaker in having French and German characters speaking their own languages with English subtitles. (A famous example of a multilingual film in Europe was La grande illusion (1937) with its mix of French, German and English.) Of course our English airmen would not understand, or be unlikely to understand, Dutch or German, and Powell and Pressburger intended for this dialogue to be untranslated. (For more on this, see “sound and vision” below.)

Of course, in wartime, naturalism couldn’t extend to actually shooting in the Netherlands, so the scenes in the Dutch countryside were actually shot in Boston, Lincolnshire, and the Dutch and German characters are played mainly by British actors, plus one Australian in Robert Helpmann, making his cinematic debut. The Wellington bomber was a “shell” supplied by the RAF to the production, and set up at Riverside Studios, Hammersmith. The script was changed during production to allow for advances in wartime technology as they came to light, to make the film as up-to-the-minute as possible. These included the floating platforms, or “lobster pots”, to aid airmen who had come down in the North Sea, which play a part towards the end of the film.

Further down the cast are familiar names such as Alec Clunes and Hay Petrie as a Dutch church organist and burgomaster respectively. Making his feature film debut at age twenty was Peter Ustinov, without a beard, as a priest. Powell appears briefly as a despatching officer. Among the crew were two future directors in other roles: Ronald Neame as the cinematographer and David Lean as editor, with a reputation of being one of the best in the business at his time. It was Lean who suggested to Powell that they delete a short scene, which became the seed from which a much longer film grew, the following year: The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp. While that film began the run of the Archers’s masterpieces, through the rest of the War and to the end of the decade, One of Our Aircraft is Missing is a step on the way to them, more naturalistic (and insistently so) than many of those later films, and without the touches of fantasy, or heightened realism, that mark them. It is very well served by this BFI Blu-ray release.

One of Our Aircraft is Missing went on release on 24 April 1942 in London. It was nominated for two Oscars: Powell and Pressburger for Best Original Screenplay, Neame and sound recordist C.C. Stevens for Best Special Effects. One of the film’s admirers was Noel Coward, then looking to make his own film to contribute to the war effort. He hired most of the film’s crew, promoting David Lean to co-director, and the result, released in September 1942, was In Which We Serve.

The BFI’s Blu-ray release of One of Our Aircraft is Missing is a single disc encoded for Region B only. The film itself has always had a U certificate, but the package is raised to a PG by the presence of The Volunteer, originally a U but now upped a certificate due to “discriminatory behaviour, rude gesture” as per the BBFC. The other extras are all documentaries, or dramatised documentaries, which all received a U at the times of their releases and wouldn’t get higher now, so have been exempted from certification.

One of Our Aircraft is Missing was shot in black and white 35mm and the Blu-ray transfer, from a 2K remaster of a fine-grain duplicating positive held by the BFI National Archive, is in the correct ratio of 1.37:1. It’s a fine transfer, with blacks, whites and greys as they should be and grain natural and filmlike – a lot of it in places, particularly in process shots involving rear-projection.

The soundtrack is the original mono, rendered as LPCM 1.0, and is clear and well-balanced: no music score, as mentioned above, but certainly dialogue and sound effects. There are two sets of subtitles optionally available, on the main feature only: one set translating the Dutch and German dialogue (not forgetting the Latin) and the other hard-of-hearing subtitles. The first set is a little contentious, as this dialogue went untranslated on the film’s original release, as Ian Christie mentions in his booklet essay. (My only previous viewing was on television, a long time ago, and I don’t remember if this dialogue was translated then.) This wouldn’t be only time foreign-language dialogue was left untranslated in a Powell and Pressburger film: for example, some Gaelic in I Know Where I’m Going! and German in Blimp.* The last disc I reviewed of a film with intentionally untranslated foreign-language dialogue was the BFI’s release of Radio On, where the hard-of-hearing subtitles rendered the German dialogue in German. That could have been a potential solution here, but in any case you can play the film with no subtitles at all if you wish.

Audio commentary

Ian Christie is an acknowledged authority on Powell and Pressburger, and this newly-recorded commentary is as informative as you would expect, with few pauses. It covers the film’s inception, production and release, and its place in Powell and Pressburger’s filmographies, very ably.

An Airman’s Letter to His Mother (5:46)

This short film from 1941 was inspired by an anonymous letter that had been printed in The Times of 18 June the year before. With fears of German invasion at a height, the letter clearly struck a chord with the British public. The newspaper reprinted the letter as an illustrated booklet which had sold half a million copies by the end of the year. Powell’s voice introduces the film, which shows us around the airman’s bedroom (one constructed for the film, not his actual one). John Gielgud reads a shortened version of the letter. In its themes of serving one’s country and of sacrifice to that end, it’s very moving. The bedroom may have been reconstructed, but the portrait at the end is of the actual airman, revealed later as Flying Officer Vivian Rosewarne, killed at the Battle of Dunkirk.

The Volunteer (44:11)

This item, like the next one, is on the borderline between a long short and a short feature. Ralph Richardson had begun his screen acting career in the 1930s but with the outbreak of war he signed up for the Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve as a pilot in the Fleet Air Arm. By 1943, he had become, as the film’s credits put it, Lt-Cmdr (A) Ralph Richardson, R.N.V.R. His war commitments had preventing him playing Godfrey Tearle’s role in One of Our Aircraft is Missing, but he had been released in 1942 to play the lead role of a Dutch shipyard chief engineer in The Silver Fleet, which Powell and Pressburger had produced but not written or directed. The Volunteer, a semi-documentary about the Fleet Air Arm, was Pressburger’s idea and he was the one who cast Richardson in the lead role. Pat McGrath was the only other credited actor, but in the film you can see Anthony Asquith, Laurence Olivier, Anna Neagle and Herbert Wilcox as themselves, and indeed Powell as a photographer outside Buckingham Palace. Richardson is first seen preparing for the stage role of Othello, with the help of his dresser Fred Davey (McGrath). The film follows Davey as he signs up for war service, aboard HMS Indomitable as it suffers an attack from dive bombers in the Mediterranean. The Volunteer, made between Colonel Blimp and A Canterbury Tale, is an odd, rather quirky film that’s a minor piece in Powell and Pressburger’s filmography, but as the intended contribution to the war effort, it certainly does its job.

Target for To-Night (50:02)

Another bit of filmographic pedantry, or exactitude if you prefer: this film is always known as Target for Tonight, even in the BBFC certificate at the start of the transfer on the Blu-ray, but it is actually spelled on screen with a hyphen, as above. Scottish-born Harry Watt had begun working in documentary before the War, at first with John Grierson and Robert Flaherty. As a director himself, he had had at least one classic under his belt with 1936’s Night Mail, which he co-directed with Basil Wright. In 1941, Watt proposed a film to the Ministry of Information, showing the progress of a bombing raid. So, if One of Our Aircraft is Missing is the fictional story of B for Bertie, Target for To-Night is the true story of F for Freddie. Well, up to a point. Names and places were disguised for security reasons, so RAF Mildenhall, where much of the film was shot, became Millerton Aerodrome for the duration of the film. Some of the film was shot on studio sets at Elstree and Denham and models were used to recreate the bombings themselves. The cast are mostly servicemen and women playing versions of themselves, though some actors appear, for example Gordon Jackson as a rear-gunner. Sadly, many of the airmen in the film didn’t live to see the end of the War. The film, edited by Stuart McAllister, was a commercial success, despite its short length, and won an honorary Oscar. Footage from it features in the 1973 television documentary series, The World at War.

The Biter Bit (14:19)

Ralph Richardson again, this time narrating a 1943 Ministry of Information short produced by Alexander Korda. Featuring new footage as well as material from previous films (including Target for To-Night and Humphrey Jennings’s Fires Were Started), The Biter Bit details the devastation caused by the Blitz in order to justify Britain’s response, targeted (at least in theory) on the Nazis’ war industrial sites. The narration was written by Michael Foot, then a journalist, later a politician and leader of the Labour Party from 1980 to 1983.

Image gallery (3:54)

A self-navigating show including production and front-of-house stills, and one poster design (Australian).

Booklet

This is one of two items available for the first pressing only. The other is a perfect-bound reproduction of Pressburger’s storybook based on the film, which was not received for review. The booklet runs to thirty-six pages plus covers.

The booklet begins with Ian Christie, whose piece “Inaugurating the Archers”, which begins by saying that the film doesn’t share the acclaim of the films Powell and Pressburger made on either side of it. The article talks about the inception of the film, and Powell’s wish to acknowledge the heroism of the people of the Low Countries risking everything to help crashed airmen to escape back to Britain. Inevitably this overlaps with Christie’s commentary, but it’s a good overview of the film. Next up is Professor Sarah Street, with “Women and the Spirit of the Resistance in One of Our Aircraft is Missing”. As mentioned above, Powell was keen that the film not be an all-male affair, and so the three leading figures of the Resistance helping the airmen to safety were all women, played by Pamela Brown (in her screen debut), Joyce Redman (who only made five cinema films, and it would be twenty-one years before her next, Tom Jones, for which she earned an Oscar nomination) and Googie Withers. Street locates One of Our Aircraft is Missing in the context of Powell and Pressburger’s other strong female roles (Deborah Kerr times three in Blimp, Kerr, Kathleen Byron and others in Black Narcissus, and so on), and discusses the ways they are presented: Withers’s Jo often in trousers with an overtly military demeanour, but donning a dress for the night before the airmen’s escape. Next we have the words of Powell himself, in an extract from his autobiography where he talks about the casting of the film. The booklet also contains contemporary reviews from the Monthly Film Bulletin and the Motion Picture Herald, notes on and credits for the extra features, and stills.

Often overlooked compared to their other major films of the 1940s, Powell and Pressburger’s One of Our Aircraft is Missing holds up very well, eighty years after its original release at the height of wartime. The extras on the BFI’s disc make it a worthwhile purchase on its own.

|