| |

"I needed to create the kind of woman I admire, who keeps the world turning without making a song and dance about it. I needed Sue." |

| |

Director, Michael Powell from his 2nd volume

of auto-biography, Million Dollar Movie |

I can't think of three more ill-suited characteristics stuffed into one blighted individual; abject alcoholism, self loathing and the skill of being able to defuse bombs. It's like putting a chronically depressed Freddy Kruger in charge of a petting zoo. Scientist and bomb disposal expert, Sammy Rice, has a grudge against the world. In his past, during one of his highly dangerous jobs, one assumes, he lost a foot. The resulting pain of its absence and chafing against the tin simulacra he subtly limps on throughout the movie, cannot be dulled by prescription pills. There's only one thing that can help – not to dull the pain but to blur the sensation so it ceases to bother him; whisky. But if he drinks whisky, he can't stop. To quote the curse of the alcoholic from Lost Weekend, "One is too many and a hundred is not enough." It's the middle of WWII and the boys in the 'small back rooms' work to crack Nazi codes, to collate performance figures of new ordinance and when push comes to 'Kaboom!', make small, intimate gestures prising open unyielding metal tubes. Make the smallest mistake during the latter and your remains are gorily scattered before cremation. The one thing you really don't need on that job is alcohol related delirium tremens... Shake and it's all over.

Alcohol is a wonderfully awful thing. It's also awfully wonderful. It faces chronic pain in the other direction, it nullifies boredom by creating a party out of your own limbs and nervous system and like a puppy with claws the length of its own spine, it jumps up and rips you to pieces with the nagging communicated thought, a persistent Father Ted's Mrs. Doylesque, "You want me, don't you? Go on, go on, go on, go on..." And that puppy's an unrelenting bastard, like Ben Kingsley in Sexy Beast. But don't worry if it gets its twelve-inch claws into you. After the third drink, you won't care. The curse of the alcoholic mindset is simple. One drink clamours for the second, a second that screams for the third and so on until you're either unconscious, asleep (same thing?), sick and unconscious or dead. But stay within the sober and the unconscious and there's a whole barrel (ho hum) of fun to be had. Pity the long term effects are frankly disastrous but then a life without booze (and therefore the acceptance of mankind's absurd double standards – alcohol, OK, grass, evil) would be, on sober reflection, a sober reflection of a life off the leash on the lash. I must give a nod to wit and BBC Radio 4 regular Clement Freud who died a few days ago as it was he who came up with the idea of life without its sins lasting longer but being not worth living.

My own love-hate relationship with booze (I love drinking and I hate not drinking) gives me enormous sympathy for our bomb-defusing hero. Add that to the marvellous craft of director Michael Powell, the subtlety of the script, the truth of the performances, a sublime hallucination and the nail biting denouement, and The Small Back Room takes its well-deserved place as a frequently overlooked gem. Powell's direction seems relatively straightforward but there are camera movements and tracking shots that draw you in, almost invisibly. He uses the terrain of his lead actors' faces in big close ups to intensify the emotion of the scenes and the script features stand out dialogue, bravura moments which testify to the talent of the writer of the novel on which the film is based (Nigel Balchin) and collaborators Powell and Pressburger.

The knock out line at the start of the film, a defiant "I'm sober..." from star David Farrar, is the tip of the ice cube. As a statement it informs the audience that our hero has a drink problem by saying exactly the opposite (the birth pangs of deeply satisfying subtext). The performances of his lover, Sue (the terrific and sensuous Kathleen Byron) and new best friend, co-defuser Capt. Dick Stuart (played solidly by a young Michael Gough) when approaching Farrar are quietly knowing and superbly crafted. There is no judgement on show here. Their eyes ask the question, the answer of which tells us all we need to know about our tortured hero.

It seems as if Jerry (the derogative but rather sweet name that the Brits called the Germans during WWII) is dropping unexploded bombs that go off when tampered with. Children are being killed by these seemingly harmless tubes and Gough wants help in finding out how these bombs (not literally) tick. Farrar agrees to help, to be on call 24/7. Gough is unaware of Farrar's drinking issues but soon understands without taking the moral high ground. We discover that Farrar is an important but lower cog in his organisation. His self confidence is in pieces and he can only stand being at home if his lover is there too. He's rarely alone with the whisky bottle he keeps next to a photo of his support mechanism (Sue).

This is an addict's insurance policy, like an ex-smoker with a packet of Silk Cut in the folds of their bags... "just in case..." Alcoholism is not simply illustrated by a staggering drunk slurring his/her words. It's much more insidious than that. It is a dark state of mind named in the movie as that "Noble Remedy". It is a remedy of sorts, solving a host of short term problems by chemical imbalance and then, once the deed is done, its effects leave the body to pick up the pieces. In short, it's a painful transaction. You pay for the credit with an almighty debit – or so I'm told. As galling as it is to my friends and despite my heady nights of revelry and half-lidded crooked smiles, I've never suffered a hangover so have no emergency brake. I guess that makes booze all the more attractively dangerous.

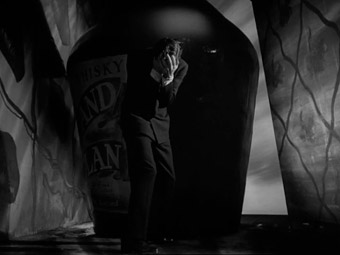

But if booze ever had a positive impact on cinema (not counting the preferred working prop for directors like Sam Peckinpah and Oliver Stone), then it's in this movie. Hard to believe but the stand out sequence in The Small Back Room was originally slated to be removed. It was Powell who'd gone 'artist' and it was felt audiences wouldn't get what Powell was doing, so different in style was it to the rest of the film. What he was doing, and succeeding effortlessly shooting in the German expressionist technique, was cinematically showing what it felt like not to want a drink, not even to need a drink. Powell was showing us a life, only alive with the promise and fulfilment of alcoholic excess – the answer to short term and unbearable temptation. Such is the power of our own minds and what happens when we give up that power to a force we believe is outside our own selves. The whisky bottle becomes some monstrous creature that we can't control and time, a construct that enslaves us. Once you're convinced that whisky is the answer to your problems, then your life becomes the problems. There is nothing but the relentless ticking and the looming bottle. Life has nothing else to offer. It is a bravura sequence and Farrar is superb as the tortured, hallucinating alcoholic.

As Sue returns to find him on the brink of a drink, he runs out (blaming her for not being there of course, the curse of all semi-functioning alcoholics - someone else's fault) and there follows a prime example of dialogue that reveals so much with so little. Sue loves Sam so much, she offers her body as a sort of scapegoat to Sam's frustrations, resentments towards his own weakness he may have paid a prostitute to receive. Take a look at this...

Sue: Where were you going Sammy?

Sam: I don't know.

Sue: A woman?

Sam: Maybe.

Sue: How about me?

That's terrific screenwriting, 1949 or 2009.

There are other peripheral pleasures to be gleaned from the movie. Sid James as a caring bartender; future director, Bryan Forbes as a dying bomb victim; Patrick McNee (yes, Steed of The Avengers) as a civil servant and I swore I saw Jonathan Lynn (sometime actor/director but notably to me as co-writer and creator of Yes, Minister) taking a private phone call in Farrar's office but as he was six years old at the time I could have been mistaken. But of course, the big set piece (as Powell says in his autobiography, a sequence beloved by directors and film students alike) is the final bomb defusing. It's seventeen minutes of quite agonising suspense and Sam is nursing a hangover. Nothing like the promise of imminent explosive death to sharpen the dullest of whisky sodden minds. I won't give anything away but I will finish with an honest statement from Farrar at a nightclub acknowledging his own shortcomings.

Sam says to Sue as she shows herself more than equal to the task of molly coddling (up to a point) this man with a boy's chip on his shoulder; "You've got it all worked out in the way women always have. They don't worry about anything except being alive or dead." It lightened my heart to see some Afghani women march last week in Kabul against the absurd Sharia law that was reported to permit rape inside marriage. I sincerely hope they are the leading foam of a giant wave of dissent and secular rationalism and humanism. Strong women make the world a better place. Michael Powell knew that. His superb The Small Back Room is one of his salutes to them.

Framed in 4:3, this 1949 movie has the original BBFC title card at the start which just sent my memory scuttling back to the Children's Film Foundation efforts we used to be shown as Saturday morning treats. Taken from a well-used print, the worst damage (dust spots and tramlines) is at the heads and tails of the original 20 minute reels. This makes practical sense, the ends and starts of the reels being more vulnerable to damage from start up and run out. Grain is noticeable in low light conditions especially at the jazz nightclub. The contrast range is fair to middling, close ups being better at bringing out richer blacks but on the whole the state of the print doesn't detract too much from the experience of the movie itself. But then again, it doesn't help to suddenly get a light grey tramline down the gorgeous face of Kathleen Byron.

The Dolby Digital mono soundtrack is acceptable. There's never a problem understanding the English and despite its age, it's scrubbed up rather well. There are no other language tracks, subtitles or close captions.

Alas, not a ration-book sausage. Yes, it's difficult to resurrect Powell and Pressburger for a film-makers' commentary but we all know that this movie has powerful friends in the Hollywood community (take a bow Martin Scorsese) not least P&P expert Ian Christie. Still, potential extras for another release (a cleaner one perhaps).

The Small Back Room is a worthy addition to the Powell and Pressburger canon and a terrific movie in its own right full of wonderfully real performances. When released in 1949 it wasn't successful more due to the fact that the public had had a belly full of war pictures. Sixty years later we can see it as it is, a superlative character driven piece with some startlingly good dialogue, a singular hallucination scene, a nail biting finale and subtle direction throughout. Well recommended.

|