|

Radio On opens with a statement of purpose: a long take which transports us around a Bristol flat, up the stairs and passing the bathroom, where the body of a man is lying in the bath. This shot was achieved by means of a Steadicam, one of its earliest uses in a British film. And the soundtrack: we’re listening to the synthesiser-and-guitar chug of David Bowie’s “‘Heroes’”, which an audience in the film’s year of release, 1979, would have recognised as a number-twenty-four hit single from two years previously and the title song of Bowie’s album of the same name. Halfway through, the track morphs from the original to Bowie’s German-language version (“Helden”) before reverting to the English. Radio On is a very English type of road movie, but it has (West) German DNA too, and that’s a combination set up from the start.

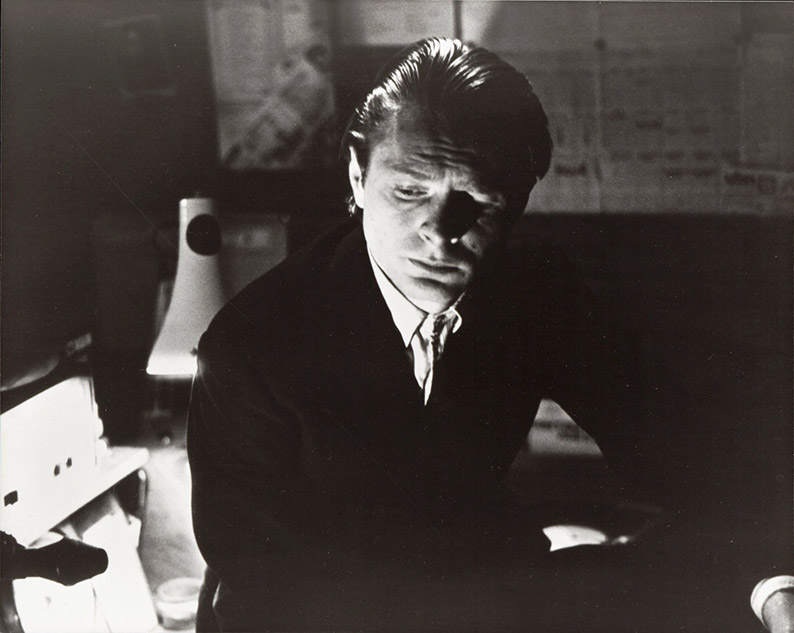

The dead man in the bath is the brother of Robert (David Beames), based in London and working as a DJ. When he hears of the death, Robert gets in his car and drives to Bristol, to see what has happened.

After the boom of the 1960s, British film production was in a slump for much of the next decade, in part due to American majors’ investment in the UK going away. At the top end, budget-wise, of what was left were the Bond films, but there were a lot of television spin-offs, softcore sex comedies and horror, both Hammer’s half-decade decline and fall, and the lower-budgeted, grittier, sleazier and more violent kind directed by Norman J. Warren, Pete Walker and others. Some directors, who had broken into cinema features in the 1960s or the start of the 1970s, could not get another big-screen film made and spent the rest of the decade working for television: Ken Loach, Stephen Frears and Mike Leigh among them. The BFI Production Board helped some small-scale, often experimental films get made, such as the early trilogies of Bill Douglas and Terence Davies. And Radio On, which was a coproduction between the BFI and Wim Wenders’s company Road Movies Filmproduktion GmbH, written and directed by Christopher Petit. If Radio On is unlike other British films of its time, it’s because its influences are from elsewhere, not the literary originals and bias of much British cinema, but something more...well, European. Wenders’s influence weighs heavily, and Petit was also harking back to another road movie earlier in the decade, Monte Hellman’s Two-Lane Blacktop.

Petit had been the films editor for Time Out, but had been dissatisfied, feeling that film criticism was not really his vocation. He wrote the first version of the script in 1976. While interviewing Wenders in the course of his day job, he mentioned the script and, possibly politely, Wenders agreed to read it. Wenders expressed an interest. How would it be made? 35mm black and white, was Petit’s reply. And who would direct it? Petit hadn’t thought of that. Maybe Wenders...but he was too busy with his own career, which would soon take him to America. So maybe Petit could direct it himself. Wenders’s company came on board as a production partner, the result of which was that the film needed to have some German input. So Martin Schäfer, assistant to Wenders’s regular cinematographer Robby Müller, became the film’s DP (and Steadicam operator in the sequence referred to above). Wenders’s sound recordist Martin Müller came on board too, and the key role of Ingrid, the woman David meets in Bristol, was given to Lisa Kreuzer, who was Wenders’s wife at the time.

I’ve said above that Radio On is unlike other British films of its time, and I’ll stand by that. It’s not an obvious commercial prospect to say the least, and anyone with a fine-tuned pretentiousness trigger will find this a barn-door-sized target. There’s very little plot in the usual sense, with what would be major story beats in a different film elided. (We never really find out the cause of Robert’s death, but it would seem that he was involved in the porn ring busted by the police, which we hear about on David’s car radio more than once. In his brother’s flat, Robert watches a hardcore slide show, a surprisingly explicit scene for the BBFC to pass, but they did, and this Blu-ray transfer begins with their X certificate.) Some dialogue is in German without English subtitles. (No, the hard-of-hearing subtitles won’t help you – see below.) And at the end, nothing is really resolved, with Robert’s car left on the edge of a quarry and his hopping on to a train, destination somewhere unknown, reached after the end of the film.

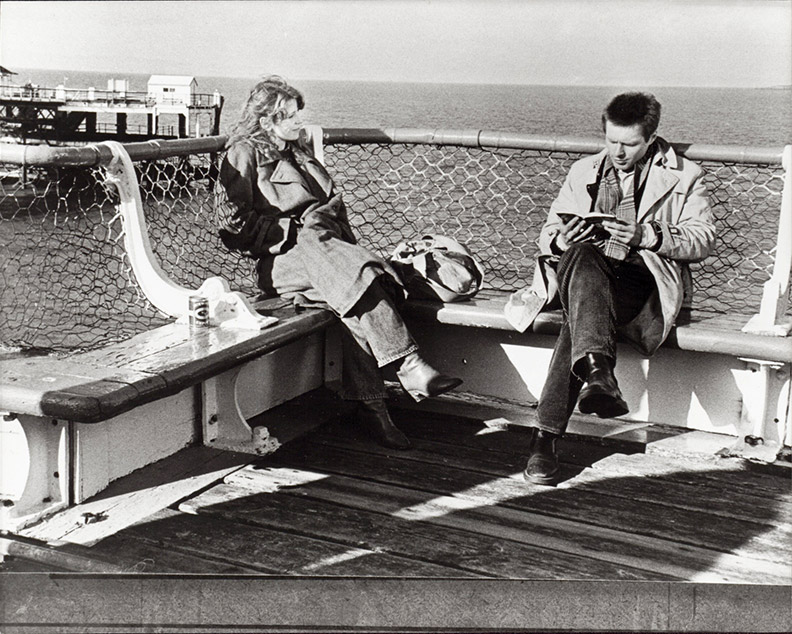

That’s all true, but rather beside the point: as with Wenders’s road movies (Alice in the Cities, Kings of the Road) and for that matter Hellman’s, it’s not the destination that’s key, but the journey itself and the people met on the way, One of those is a soldier (Andrew Byatt) who is AWOL from his tour of Northern Ireland. Another is a petrol-station attendant (Sting), who is a fan of Eddie Cochran, killed in a road accident nearby, and who plays “Three Steps to Heaven” on his guitar.

Radio On conjures up a late-Seventies landscape of motorways and apartment blocks which establishes our protagonist’s alienation, and that of others, made less ugly and oddly timeless in Schäfer’s monochrome cinematography. Forty-two years on, Radio On is a showcase for 35mm black and white cinematography, then a vanishing art, now even more so, though recent films such as The Lighthouse still keep the medium alive. Black and white had ended as a continual tradition, in major-studio English-language releases at least, a decade earlier, and since then black and white has been the exception to the colour norm. However, even by the end of the Seventies, some of those exceptions were being shot on colour stock and printed in monochrome. More recently, many have been digitally captured and post-produced in black and white. One reason why Radio On did look as good as it did was the fact that Rank Film Laboratories brought their most experienced grader of the medium out of retirement to process the film. That wasn’t entirely without a vested interest, though. Rank were aware that The Elephant Man was on its way, and they wanted Radio On to be a showcase for them so that they could get the work of processing the Lynch film, which they did.

However, Radio On quickly gained a cult following, not least for its use of music. You sense the makers realised this, as apart from the production companies, the names of the three lead actors, all that we see at the start are the music credits. (The film doesn’t in fact have a title card. In an odd connection with a very different black and white film from the same year – Woody Allen’s Manhattan – the title only appears diegetically, as a sign.) As well as Bowie (producer Keith Griffiths had a connection with him), we hear several tracks from Kraftwerk, which certainly add to the German road-movie ambience. Also, there are several cuts from Stiff Records artistes, such as Wreckless Eric, Ian Dury, Devo and Lene Lovich, plus Robert Fripp, in his own right as well as the lead guitarist on “‘Heroes’”.

Petit’s career as a feature-film director was short-lived: just three more films in the 1980s, a dark and stylised adaptation of P.D. James’s An Unsuitable Job for a Woman (1981) and two more Euro-inflected films, Flight to Berlin (1983) and Chinese Boxes (1984). By the end of the decade he was directing a Miss Marple mystery, A Caribbean Mystery, his last fiction feature to date. His films since then have been documentaries, several of them excursions into psychogeography in collaboration with Iain Sinclair, and he has also published seven novels. However, Radio On, if you surrender to it, casts its own spell, and it gains with repeated viewings.

The BFI’s Blu-ray release of Radio On is a single Blu-ray encoded for Region B. The BFI previously released the film on DVD in 2009, and some of the extras for that release have been carried forward to this. Given an X certificate in cinemas, Radio On is now an 18. Among the extras, Coping with Cupid is a 12.

Radio On was shot in 35mm black and white on Ilford film stock, as the end credits helpfully tell us. The Blu-ray transfer is in the original ratio of 1.85:1 and is derived from a 4K scan of the original negative and a fine-grain duplicating positive. Schäfer favoured Ilford over the more usual Kodak Double-X (still in use today), and the results feature some strong blacks and a wide greyscale – those are English skies, after all.

The soundtrack is the original mono, rendered in LPCM 1.0. As mentioned above, some dialogue exchanges in German do not have English subtitles to translate them, which has always been the case with this film. English subtitles for the hard-of-hearing are available for the feature only, not for the extras. That German dialogue is transcribed in German so you do at least have the chance to practise the language if you aren’t German-enabled, or if, like mine, your command of the language is very rusty. I’d imagine many other companies would simply have subtitled these exchanges as “[SPEAKING GERMAN]” or similar, so that’s a commendable further step on the part of the BFI, and it was the case with the DVD release too.

A Little Bit Kitsch, but Ice Cold: Retro-Futurism in Focus (51:32)

A high-flown title for what is in effect a commentary track, or at least half of one: Christopher Petit is interviewed by the BFI’s Vic Pratt, in an audio-only item new to this release. Petit goes through the inspiration for the film and its making, discussing some key scenes. One issue inevitably is that quite a bit of this interview overlaps with what Petit says in his 2009 interview (see below), albeit with some updates in the twelve years since. This item plays as a second audio track over the feature, finishing about halfway through, after which the film’s audio takes over for the rest of the running time.

Cinematic Windscreen: Jason Wood on Radio On (55:37)

This is also new to this release, as if you couldn’t guess while watching it. It has all the Covid-era signifiers present and correct: Wood talks directly to camera, with an enviable collection of film books on the shelves behind him. Vic Pratt is again the interviewer, but his words have been edited out, so this becomes a Wood monologue subdivided by captions.

This isn’t the only appearance by Wood on this release, and it’s fair to call him a Radio On superfan, having spent part of his life watching the film repeatedly. His first viewing was when his brother brought home a VHS copy, when Wood was strictly speaking too young to see the film. It remains one of his favourite films, another being Antonioni’s The Passenger, to which he compares it.

Interview with Chris Petit and Keith Griffiths (42:15)

This item was included on the 2009 DVD release. Petit and Griffiths are interviewed separately at the BFI Southbank, their responses edited together and the whole subdivided by captions. Jason Wood was the offscreen interviewer, but as per usual, he’s edited out, leaving just those captions and the interviewees’ responses to camera. There’s more Petit than Griffiths here, but it’s a thorough piece on the film from inception to production to release, with discussion on the music track (including the names of a couple of tracks they weren’t able to use) and the film’s critical reception and afterlife.

Radio On (Remix) (24:15)

Produced for the film’s twentieth anniversary in 1999, Radio On (Remix) was made for HTV (Harlech Television, which was the ITV franchise holder for Wales and the West Country, including the Bristol area, between 1968 and 2013). It takes footage from the original film, with Hi-8 video footage of the locations as they were in 1999 (sometimes quite different), with a soundtrack “disrupted” by Bruce Gilbert of Wire. Very much a conceptual piece, this video essay may well enchant or if not will likely try your patience.

Coping with Cupid (18:58)

A feature of many BFI releases are extras, often sourced from the BFI’s archive, which are not directly relevant to the main feature but off on a tangent to it, often taking up one of its themes. In this case, it’s the New Wave soundtrack, and a member of that movement, Viv Albertine, guitarist of The Slits. Coping With Cupid was a short film, shot on 16mm, that she directed in 1991 for the BFI Production Board. Among its showings was as part of a triple bill at the Scala Cinema in King’s Cross, London, with the cult porn/SF movie Cafe Flesh and Russ Meyer’s Up! That’s no doubt a very strange programme, as Coping with Cupid is very much influenced by film theory and with Brechtian alienation effects thrown in. Three aliens arrive on Earth in the form of three blonde women (Yolande Brener, Fiona Dennison, Melissa Milo) sent here to investigate what humans mean by love. The fact that the form they take is one of femininity to the max (big hair, tight dresses, high heels, lots of makeup) is no accident. Along the way the three aliens meet psychoanalyst Liz Green, feminist writer Ros Coward, film historian John Noble, and, on a television screen, sexuality researcher Shere Hite. The short film is funny, which is in its favour. Presented in a ratio of 1.33:1.

On the Road

A section of the extras menu, containing two short films made for the Central Office of Information.

L for Logic (13:51)

The prequel to Radio On, or indeed any other road movie: the driving test. It was made in 1972 and intended to show learner drivers what they could expect from a test.

The Motorway File (33:12)

More than twice as long, The Motorway File dates from 1974. It begins with the scene of a motorway accident, a fatal one. We then cut to narrator Edgar Lustgarten, who talks to camera as we follow AA man Eddie Johnson and four other drivers, three men and a women. There’s a somewhat ominous tone to this, as when a salesman leaves the B & B he’s stayed in, or another man leaves home, director Ferdinand Fairfax cuts to people nearby turning to stand and stare: a cleaner at the B & B, a woman putting her milk bottles out, the man’s wife watching from the window. All four drivers, however experienced they are, exhibit behaviour which could be dangerous: driving while tired (and hung over from the night before), driving too fast, staying in the outside lane too long, or even lack of confidence on the motorways. But we know that there will be at least one fatal accident before the film is over – but who will it be? As well as director Fairfax (who worked mostly on television in his career) there are some distinguished names in the credits, including editor Thom Noble and co-cinematographer Alex Thomson (spelled Thompson here). Both COI films were shot in 16mm and are presented in 1.33:1.

Theatrical Trailer (3:14)

You have to wonder how you could sell a film like Radio On back in 1979. The makers of this trailer clearly felt that the music was the draw.

Image gallery

Twenty-eight images, which unlike most BFI Blu-rays aren’t self-navigating, or at least weren’t on the review checkdisc I received. So you’ll have to advance one by one using your remote.

Booklet

Available with the first pressing only, the BFI’s booklet runs to thirty-six pages plus the cover. There’s a spoiler warning at the start, so watch the film first before reading the essays within. We begin with Jason Wood and “Radio On: Celluloid Jukebox”. As with his video appreciation, Wood makes no secret of his love for the film, but he does give a fair amount of coverage of Petit’s inspiration for the film and its use of music in particular. This is followed by a piece by Geoffrey Nowell-Smith, revised from an essay that originally appeared at the time of the film’s release in Screen (Winter 1979/1980), a review but one which clearly understood what the film is about and how it achieves its aims. Ian Penman looks at the film’s soundtrack and finds it key to how the film has only superficially dated, comparing it with D.A. Pennebaker’s Don’t Look Back, with its many scenes of Bob Dylan on tour, in hotel rooms and cars, with talk aimed at making connections and often failing to. Another essay follows, this one “Border Zones” by Sukhdev Sandhu, reprinted from another DVD release (Plexifilm’s, not the BFI). Petit next looks back on his own film, embracing the fact that a good few people were bored by it, and it was savaged by some other critics who may have had scores to settle given that Time Out had criticised them. He also talks about the influence of the French writer Louis-Ferdinand Céline, and his novel Journey to the End of the Night, which only one critic picked up on. Rudy Wurlitzer, writer of Two-Lane Blacktop, contributes a two-paragraph piece calling the film “a melancholy requiem from another time, another place”. The booklet also contains film credits, biographies of Petit and Griffiths and notes and credits for the extra. Coping with Cupid has a note from Viv Albertine about her film, and Jane Giles contributes an essay on the short. Also in the booklet are stills and transfer notes.

Radio On never set the box offices alight, but it quickly developed a cult following and it remains the one feature of Christopher Petit’s short feature-film career which has lasted. While the film certainly won’t be for everyone, the BFI’s Blu-ray release is exemplary.

|