|

It's been a while since I've reviewed anything for Cine Outsider, and there are sound reasons for that. No, I'm not going to elaborate further. But the stars finally aligned, and the right title at the right time – coupled with the need to take the pressure off of otherwise insanely busy people – brought me back into the fold. And spoiler warning, I'm so glad it was this set that did so.

For those of us who were under the mistaken impression that Mexican movie horror really began with Guillermo del Toro, Indicator's release of the 1933 La Llorona and the 1934 The Phantom of the Monastery [El fantasma del convent] was a genuine revelation. It made me realise just how little I knew about the country's genre cinema, and I was keen to see more. Now, having given us such a delicious taster, Indicator is back with a varied quartet of horror-themed works from a four-year period between 1959 and 1963, when the Mexican horror wave was at its peak.

I went into this set having no idea what to expect, and was thrilled to smithereens by what I encountered, though am still convinced it was The Brainiac that resulted my name being put forward to cover it. I'll get into why below. For many, these films will be virgin territory. They certainly were for me. But oh, these movies, and these discs. There's so much here to get to grips with here, so let's start with the films themselves.

THE BLACK PIT OF DR. M

[MISTERIOS DE ULTRATUMBA / MYSTERIES OF THE AFTERLIFE] |

|

The ominously titled The Black Pit of Dr. M opens with a series of atmospheric shots (and one oddly timed edit) of a decrepit and boarded-up building, accompanied by narration that assures us that what we are about to see is a true story (I don't think so). It then takes us back to a time to before this location fell into ruin. We're in the bedroom of Dr. Jacinto Aldama (Antonio Raxel), who is lying on what is effectively his death bed. Pressed up close to him is the face of his colleague, Dr. Mazali (Rafael Bertrand), who urgently reminds him of a grim pledge that the two of them made, that whoever dies first must find a way for the other to enter and to safely return from the world that lies beyond the grave. This struck a chord with me. Many years ago, I made a similar pact with close friend of mine. We both promised that if there really was an afterlife, then whoever died first should find a way to inform the other of its existence. Sad to say, I lost my friend many years ago but haven't heard a peep since. To be honest, I never expected that I would. But this is a movie, one made in a country where Catholicism is even today still a force to be reckoned with, and so of course there has to be an afterlife of some kind.

After attending his friend's funeral, the impatient Mazali tries to get the answer he seeks by arranging a séance, though whose medium Aldama delivers a cryptic message. In three months, at a precise date and time, he tells Mazali, a door will close in front of him, opening the doors of beyond. He also tells him that starting tonight, a chain of events will occur inexorably in his life with the sole purpose of leading him to this destined moment, and warns him that there will be a horrible price to pay for following this course of action. It's a rivetingly staged sequence, particularly in its use of close-ups of faces and the sweat-drenched mouth of the medium as she delivers Aldama's words. When Mazali steps outside into his glorious horror-movie patio garden, the spirit of Almada ominously walks behind him, only to then vanish when Mazali senses his presence.

Elsewhere in the locale, handsome young doctor Eduardo Jiménez (Gastón Santos) is out with friends at a dance performance that looks as if it's been plucked from the Salvador Dali designed dream sequence in Hitchcock's Spellbound. Seriously, where is this place? Things take a strange turn when one of the dancers, Patricia (Mapita Cortés), accidentally locks eyes with Eduardo. Eduardo is entranced, but the look on Patricia's face is one of mounting horror. We soon learn that the two have been dreaming about each other, and while Eduardo is intrigued to meet the woman of his dreams, the startled Patricia anxiously packs her bag and quits. By the time Eduardo has gone backstage to meet her, she's out of there. Little do either of them know that both are destined to unknowingly help to steer Mazali towards the knowledge he seeks. You see, it turns out that Eduardo has been engaged to join Mazali's staff at the psychiatric hospital at which he is the head doctor. Patricia, meanwhile, is visited by a man who reveals to her that Aldama was her absent father, and gives her a key to present to Mazali that will unlock her inheritance, then quietly disappears. He tactfully chooses not to reveal that he is Aldama's ghost. The following evening she's in Mazali's parlour awaiting his return from work, and who should knock at the door but Eduardo, all enthusiastic to take up his new appointment. Given that the two are both young and handsome and have been dreaming about each other for some time, what do you reckon the odds are of them ending up in each other's arms?

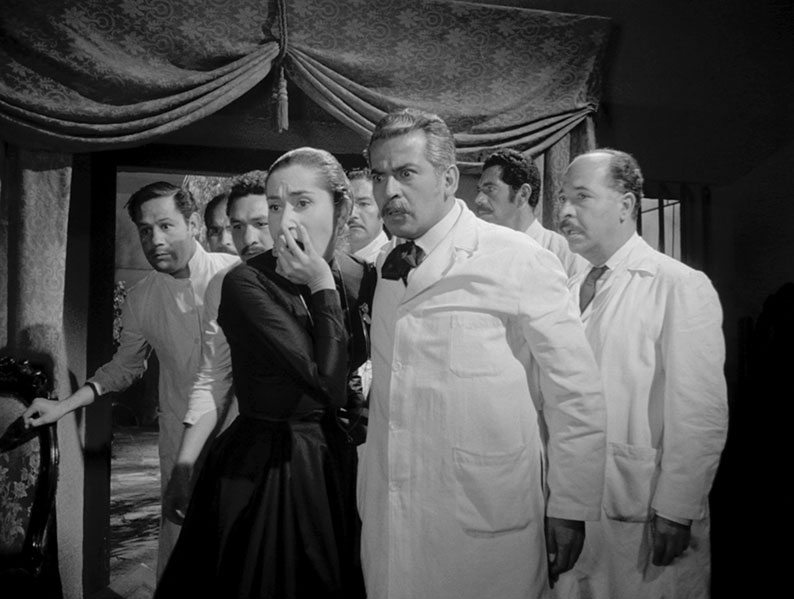

While all this is unfolding, Mazili himself is otherwise engaged at the hospital helping his colleagues to calm a violently disturbed gypsy woman (Carolina Barret) using the soothing melody from a music box. All seems to be going well until the lid of the box is accidentally closed, cutting off the music and sending the woman into psychotic rage. In the process of wrecking the surgery into which she has been so carefully led, she breaks a bottle of acid over the face of hospital orderly Elmer (Carlos Ancira). She's eventually restrained and dragged back to her cell, leaving Dr. Mazali to perform emergency surgery on Elmer in an effort to save what he can of his face. He then leaves him in the care of his colleague Dr. González (Luis Aragón) and heads home, in need of a rest from his endeavours. Little does he know, that both Elmer and the gypsy woman are also destined to play crucial roles in his quest for this dangerous knowledge.

Any uncertainties you might be harbouring about the prospect of a low-budget Mexican horror work from the late 1950s should be laid firmly to rest by this absolute belter of a supernatural thriller. From the creativity and intrigue of its eerily designed (by celebrated abstract painter Gunther Gerszo) prologue, through its arrestingly shot opening scene, the chillingly handled séance, and the spookily atmospheric wander into the garden that follows (take a bow, prolific cinematographer Víctor Herrera), this is a class act all round. Particularly impressive is its precisely structured plot, which throws a collection of seemingly random chance events at us that over the course of the film's first two-thirds move effortlessly into place, like slow-motion footage of an exploding building being played in reverse. Just how Mazali will get the proof of the afterlife that he so desperately seeks remains a mystery up until the film is ready to share one of its neatest twists. I am forbidden by spoiler etiquette from revealing what this entails, but the lead-up to the crucial moment is really something, and involves a dramatic backlit composition so audacious that I had to grasp my jaw to prevent it from dropping. It doesn't end there, as this turn of events creates new complications and sends fate in an irony-tinged spiral, landing a transformed Mazali right back in the hot seat for something he has theoretically already paid the price for.

As an introduction to Mexican supernatural horror of the late 1950s, The Black Pit of Dr. M is hard to beat. The direction by Fernando Méndez's is simultaneously creative, purposeful, and resourceful, while Ramón Obón's screenplay is tightly and inventively structured. Herrera's black-and-white photography is handsome throughout and makes gorgeous use of light and mist in the studio-created night time exteriors. The performances are solid across the board, though special mention has to go to Rafael Bertrand as Dr. Mazali and Carlos Ancira and the facially scarred and vengeful Elmer. Even the make-up on Elmer's acid-scarred face is pretty darned good. I gather from the special features that the film is held in very high regard by connoisseurs of Mexican horror. I'm not a bit surprised. I absolutely loved it.

| THE WITCH'S MIRROR [EL ESPEJO DE LA BRUJA] |

|

What is it with mirrors in horror movies? In real life they're essential items, without which we could not shave, fix our hair, or slap on make-up without chancing it all to guesswork. Yet if a mirror makes more than a passing appearance in a horror film then you can bet your bottom dollar it'll be the harbinger of terrible things. This is particularly true if it has an ornate wooden or brass frame, and was either a feature of the house that a new family has moved into or was purchased by one of the characters from a strange antiques shop. When on holiday recently, I stayed at a small hotel with modern furniture and fittings, but in the newly refurbished lobby there was just such a mirror. Every time I looked into it, I found myself expecting the reflection to suddenly change into something that would give me sleepless nights for weeks.

There's no ambiguity on this score with a title like The Witch's Mirror, which wastes no time setting up a plot that has already been brewing for some time when we join it. As the film begins, Elena (Dina de Marco) and her godmother Sara (Isabela Corona) are looking into the titular mirror, which seems to be acting as a gateway to another world. Thanks to that title and an opening narration that talks of witchcraft and its practitioners, we're able to immediately deduce that Sara is a master of the black arts and able to communicate with the sort of spirits you definitely don't want visiting you in the dark of night. We quickly learn that Elena's life is in danger, and when asked to specify the nature of the threat, the mirror serves up an image of Elena's husband, Eduardo (Armando Calvo). The fact that he's clearly a surgeon instantly had me nervously contemplating how he planned to do away with his good wife. This is then overlaid with the image of a woman whom Sara identifies only as Elena's rival. Elena doesn't know her, and Sara insists that this woman is equally ignorant of Elena. "But, unwittingly," he confirms, "she can do you great harm."

So what can Elena do to protect herself and foil her husband's plan? Absolutely nothing. Sara pleads with the powerful spirit Adonai to be allowed to intervene but is told in no uncertain terms that Elena's fate is sealed and there's nothing that anyone can do about it. She must die, Elena is unceremoniously told. When the time comes, Eduardo thankfully leaves the scalpels in his surgery and takes a leaf from the Suspicion manual and poisons Elena's bedtime milk instead. In a moment that really carries an emotional kick, Elena seems to realise exactly what her husband has done and even pleads with him for an explanation. The awful bastard refuses to even look in her direction, and grimly accepting her fate she drinks the milk, with the expected consequences. With Elena now gone, what could her godmother possibly do to avenge her? Well, here's the thing. Only when Eduardo returns from his post-funeral travels with his new wife Deborah (Rosita Arenas) – the previously unknown woman in the mirror – did I realise that Sara is actually Eduardo's housekeeper. I may be wrong, but it seemed to me that Eduardo was completely unaware that she was also his late wife's godmother. Had he known this, would he seriously have wanted her still hanging around? I think not. Keeping up appearances, Sara remains on superficially friendly terms with her master on his return, and reacts warmly to Deborah's stated hope that the two of them will become friends. Oh, will those words come back to haunt us later.

This proves the setup for a tale that could have been comfortably told in the Tales from the Crypt or Vault of Horror EC comics by way of Hitchcock's Rebecca, as the spirit of Elena makes life uncomfortable for Eduardo and the increasingly envious Deborah. Some of the disturbances have clearly been arranged by the very mortal Sara, with Eduardo losing his cool after Deborah plays Elena's favourite tune simply because she found its sheet music sitting on the piano. Other incidents have a more supernatural vibe, a personal favourite being the flowers that wither and die in seconds when placed in a vase in Elena's old room, a neat trick borrowed from the 1944 classic, The Uninvited. And when the piano starts playing Elena's music unassisted and an ill wind blows through the house and opens doors, there's clearly something ghostly afoot.

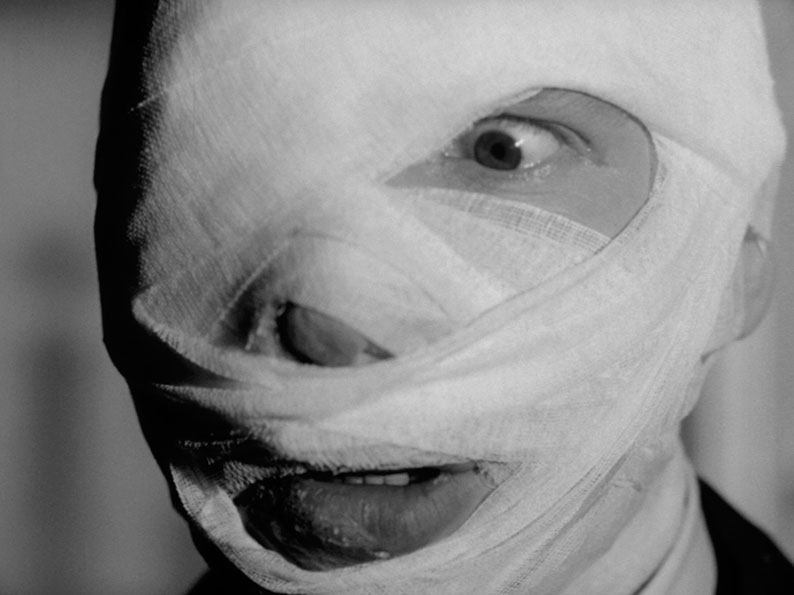

This all builds to a genuinely startling finale, and yet just as a it seems that the story has reached its fiery conclusion, the film begins its second act, and Tales from the Crypt moves into Frankenstein territory, laced with a heavy dose of Georges Franjou's Eyes Without a Face. And bloody hell, is it gruesome. Just as I sometimes still get caught out by the strength of content in pre-Production Code American movies, I too often forget that the cinema of other countries was not bound by the same set of puritan rules. In the spirit of not revealing the nature of the incident that triggers this rather delicious narrative shift, I'll avoid getting into specifics about what subsequently unfolds, but it's peppered with seriously dark deeds and a creepily effective use of the late Elena's ghostly form. As Eduardo attends to his wife's newly acquired needs with the help of loyal young assistant Gustavo (Carlos Nieto), Sara continues to secretly plot against him, in a way that ends up punishing the unfortunate Deborah for a crime that she was not even aware took place. And Sara really is the lynchpin around which the story revolves, politely serving her master and his new beau whilst simultaneously calling on dark magic to put the disembodied spirit of Elena to vengeful use. She's superbly played by Isabela Corona, whose portrayal bristles with self-confidence and is peppered with lovely touches that transform her from a matronly housekeeper into a master of the dark arts with little more than a look or a gesture. Take the moment where she manages to terrify Gustavo in a corridor of this cavernous house. He's already rattled and pressed up against the wall, but when he turns to face the window at the corridor's end, Elena materialises in silhouette, then raises her hands and glides towards him with arms outstretched in what briefly feels like sinisterly welcoming motion. She then drops her arms and walks up to him in everyday manner, but by then the poor lad is a quivering wreck. And just watch the satisfied smile that crosses her face when she hands a lamp to Eduardo as the first half of the story thunders towards its climax, then watch it again after seeing the whole film and realise just what that look is telling us.

Having been knocked for six by the first film in this set, I genuinely wasn't prepared to be similarly blown away by the second of the four titles here, but I absolutely was. In retrospect, the film does play like two differently toned chapters of the same sinister tale, with intriguing and intermittently creepy first half giving way to a second that laces the supernatural elements with grim medical horror. Even the makeup effects are way better than the film's low budget and tight shooting schedule should theoretically had allowed for. There are some small flaws in an optical effect in the finale, but this matters little in a film so otherwise expertly crafted and performed. Man, how is it that I've never seen these remarkable movies before?

| THE BRANIAC [EL BARÓN DEL TERROR / THE BARON OF TERROR] |

|

If long-time readers of the site are wondering just why I've been dragged out of technical retirement to review this box set, right here is your answer. I'll get to the specifics of that statement in a moment.

Back in 1661, the decadent Baron Vitelius d'Estera (Abel Salazar) has been hauled before the Inquisition for a whole slew of acts of proclaimed depravity, including heresy, using witchcraft for "dishonest" purposes, necromancy, attempting to tell the future using corpses (what?), and – wait for it – seducing married women and maidens. The absolute cad. He's already been repeatedly tortured but looks no worse for it and apparently just laughed in the face of his persecutors. Even as the charges are read out for what must be the umpteenth time since his arrest, he can't help but chuckle and smirk at the accusations. Unexpectedly, a witness named Marcos Miranda (Rubén Rojo) has come forward to defend him, but his testimony consists of nothing more than a claim to know the Baron is an honest man of high virtue and an apostle of science. Want to guess how that goes down with the Inquisition? Yep, he's sentenced to 200 lashes for his insolence. Lot of bloody good that did anyone. The self-proclaimed Holy Court of Mexico then sentences Vitelius to be burnt alive in an open field after having all of his property confiscated. As he stands crucified on the flaming pyre, he looks up at a passing comet and pledges that when it reappears in 300 years, he will return to kill the living descendants of the four lead inquisitors and in the process terminate their bloodlines.

If any of this sounds and even looks familiar, it's because the basics of this setup have been creatively adapted from Mario Bava's masterful 1960 Black Sunday [La maschera del demonio] and John Moxey's City of the Dead of the same year. Honestly, there are shots of the crowd watching the execution here that could be comfortably cut into Moxey's film without looking misplaced. Yet once we hop forward to 1961, The Brainiac side-lines its horror to become a 1950s-style alien invasion movie. As predicted, the comet reappears, and when it falls to earth, Vetelius is inside it. For reasons the film clearly has no intention of explaining, the Baron has been transformed over time into a demon with a forked tongue that can drill holes in the back of human heads and suck out their "encephalic mass" (that's brains to you and me). He is also able to metamorphose back into human form at will, though appears to have to kill and suck on brain to do so. After stripping an unfortunate witness to the comet's landfall of his life and his clothing, he sets to work tracking down the descendants of the men who sent him to his death.

It's an interesting enough setup, but I'm willing to bet that a good number of those raised on the slick CGI and makeup effects of modern horror are going to have a few problems with this movie. The title doesn't help, or at least the English language one slapped on it by enterprising American distributor K Gordon Murray. Nowadays, the word 'brainiac' tends to be used as pejorative slang for anyone showing intelligence in the face of group stupidity, and is thus not a title that invokes even a whiff of fear or the uncanny. Then again, the original Mexican title, El barón del terror, translates literally as 'The Baron of Terror', which while admittedly better, is a bit on-the-nose. But there's more, so much more. Oh boy, where do I start? Okay, it's clear that director Chano Urueta – yes, the hugely talented man behind The Witch's Mirror – was handed a budget that wouldn't cover the catering bill for a Hollywood studio movie of the day. This does further align it with the science fiction cheapies being made in America in the 1950s and early 60s, to which it is also bonded by the cheapness of its monster, the brain-sucking demon incarnation of the Baron Vitelius. Saddled with a Halloween-mask demon head that pulses as the actor beneath breathes in and out (I will admit that this effect may well be deliberate and intended to appear creepily otherworldly), his hands have been replaced by a couple of hollow rubbery tubes that look about as much use as the sink plungers on classic Dr. Who-era Daleks. And then there's that forked tongue, a plastic cut-out that dangles from his mouth like the stiffly unanimated prop that it is. As a result, the Demon Baron has to awkwardly manoeuvre the heads of his victims in order to get the tongue and its pointy forks into position at the back of their necks. And I'm sorry, but that tongue couldn't drill a hole in a piece of warm cottage cheese, let alone a human skull. I won't even ask how the Demon Baron extracts the brains of his victims through two holes barely wide enough to push a pencil through and somehow keep them intact.

Adding to the film's micro-budget feel is the decision to shoot all of the exterior shots in the studio using projected backdrops. I'm going to cut Urueta some slack here, as location shoots were more expensive and time-consuming than working in a studio on ready-made sets, and the whole film was shot in a seemingly impossible nine days. This may be emulating a technique that was already popular in Hollywood, but when the actors are lit differently to how the light falls on the more washed-out background image, the fakery is not so much exposed as loudly trumpeted. And oh, that bloody comet. A primitively hand-drawn image whose tail curls around so tightly you'd think it was orbiting an orange, it clearly looked so unconvincing even to Urueta that he chose to throw its every appearance wildly out of focus, presumably in an attempt to disguise its defects. At one point it's even replaced with what is clearly just a firework sparkler. At least it's animated then.

It's all comically cheapjack and makes little real world sense. And I thought it was an absolute blast. Yes, come to it unknowingly after the excellence of the two preceding films and you're likely to suffer from content shock, but for fans of low-budget, 50s sci-fi monster cinema, The Brainiac is the sort of guilty pleasure treat that I and like-minded souls used to hunt out on late-night TV screenings and at low-budget science-fiction all-nighters at London cinemas. The monster make-up looks cheap? That adds to the fun. The Baron's activities are peppered with questions and logic holes? I couldn't care less. The special effects are ropey? I'll take them any day in preference to over-produced Hollywood CG. And if it reads like I'm making excuses for the film – and I absolutely am – then know that the reason I do so is that these are all peripheral elements of what is otherwise a neatly devised and executed slice of sf-horror.

Key to what makes the film so enjoyable is the Baron himself, who is played by Abel Salazar, a good-looking actor with his share of romantic leads who was also a shrewd businessman and producer of considerable note. Not only was he one of the key instigators of the Mexican horror wave of the period, bringing in directors like Fernando Mendéz and Chano Urueta to helm the movies, he also has a producing credit on three of the movies in this set, this one included. Sir, we salute you. In his role as the Baron in the opening scene, he smirks amusingly at the Inquisition's charges, but on his return to Earth he reigns his emotions in to the point where he seems to be doing very little, but the malevolence bubbling just under the surface is always tantalisingly visible. And those good looks are put to wonderfully malevolent use, as he paralyses male victims with a hypnotic stare (created on the cheap by flashing a light on the top half of his face), then snogs the hell out of their wives while the immobilised husbands are forced to watch on. He then disposes of these descendants of his executioners – one of whom is played by Survive!, Night of the Bloody Apes and La isla de los hombres solos director René Cardona – in appropriately fire-related ways. Well, the male victims at least. There's a suggestion that something even more unpleasant inflicted on one of the female descendants. Intriguingly, this 'vengeful monster kills victims in creative ways' storyline anticipates the later slasher movie cycle, and in that respect is a good 15 years ahead of the game.

Although a man on a very specific mission, the Baron doesn't restrict himself to the men and women on his list, and he seems to like kissing almost as much and he likes encephalic mass. He kisses and then kills a flirty woman (played by the mysteriously second-billed Ariadne Welter), and responds to a come-on from a sex worker (and alluring Susana Cora) by passionately kissing her too, before transforming into you-know-what and sucking out her brain. Why does he do this? Well that's revealed in what just has to be the film's most gloriously outrageous sequence (skip to the next paragraph to avoid a spoiler that I just can't stop myself from revealing), when the Baron politely excuses himself during a swanky dinner party he is holding at a mansion he has procured from somewhere or other. As his guests socialise, he walks into a side room and opens a dresser, inside which is a bowl containing the still intact brains of his recent victims. He then spoons some of the brain matter into a goblet and… and he drinks it. I think I actually let out a small yelp at this point. It turns out that this brain sashimi provides him with the sustenance he needs to continue in human form.

Early on, we're introduced to an attractive young hero and heroine in the shape of astronomers Reinaldo (Rubén Rojo) and Victoria (Rosa María Gallardo), and it seems likely from the off that they will be the ones to ultimately foil the Baron's demonic plan. They'll need to, as it turns out that Victoria is descended from one of men who sent the Baron to his death 300 years previously. Complicating matters is that her boyfriend Reinaldo is a direct descendant of Marcos Miranda, the man who came forward to says a few nice words about the Baron at his trial, and the while he does plan to kill Victoria, The Baron is also unexpectedly attracted to her. And after the first brain-eating episode, however (yep, there's another), I began to suspect that anything was possible. Floating around the periphery, meanwhile, are two unnamed detectives, one deadly serious (David Silva) and one who looks a little like a Mexican Phil Silvers (Federico Curiel) and seems to be intended as comedy relief. Don't get your hopes up for big laughs with this guy. They at least seem a little more proactive than the pair that wait until the evidence is dropped in their laps in The Witch's Mirror.

Others will doubtless dismiss The Brainiac as a schlocky anomaly in an otherwise classy box set, and I do get that but just cannot agree. Yep, corners are cut in almost every department (that said, those brains look real enough), there are aspects of the plot that simply make no sense, and there's an aspect of the climax that I can't reveal that had me yelling at the screen is wide-eyed disbelief. But what remains is as entertaining as all hell, and despite being saddled with budget-restricted elements, director Chano Urueta still pulls off a few visual flourishes – check out the high-angle shot of the observatory interior in which Reinaldo and Viktoria's mentor, Professor Saturnino Millán (Luis Aragón) is working, or the Nosferatu inspired shadow on the wall as the Baron in monster form descends on the body of a fainted female victim. And for all its cheapness and illogicality, the Brainiac monster has apparently become an icon of Mexican horror cinema and found its way onto t-shirts, posters and the cover of this Blu-ray box set, and was even released as an action figure (I want one!). I also believe there's a potential essay's worth of creative speculation on the notion that the Baron has been circling the universe encased in a meteor for 300 years, just waiting to return to Earth to wreak his revenge. Perhaps it's no wonder that he looks like he does.

THE CURSE OF THE CRYING WOMAN

[LA MALDICIÓN DE LA LLORONA] |

|

What was I saying about mirrors in horror movies? I'll come back to that in a minute.

As far as 'what the hell?' opening scenes go, the one that fronts the 1963 The Curse of the Crying Woman is a peach. The film begins with jarring suddenness on the mid-shot of a black-eyed woman twitching in what looks like a state of agitated trauma. Underscoring the image is the sort of dramatic music usually saved for a climactic action scene, which peaks as the camera zooms in to a closeup of the woman's face. This cuts to a wonderfully lit shot of a facially disfigured man grimacing and twisting in what looks like off-screen-inflicted pain, then returns to the woman, this time in a wide shot that reveals she is standing in mist-drenched woodland with three large Doberman dogs at her disposal. Travelling by carriage through his God-forsaken region is an unnamed young woman and two top-hatted gentlemen. One of the men is nervous about their location and tells of a strange beast that is supposed to roam the region and kill its victims horribly. His companion cheerfully mocks everything he says and bursts into exaggerated laughter at every witty put-down he delivers. Theoretically, this should make him instantly irritating, but I really liked him, and looked forward to spending more time in his over-cheerful company. Which is a bit of a shame considering what happens next.

The coach is brought to a halt by the aforementioned disfigured man, who promptly throws a knife into the driver's chest. When the nervous male passenger gets out to investigate, the disfigured man strangles him, seemingly under the control of the watching black-eyed woman. In a heart-warming show of solidarity with his friend, the comical man then turns and runs away, but he's not destined to get far with three angry Dobermans hot on his heels. The woman from the carriage then faints, and for a short while I presumed she was going to be carried off by the disfigured man for the black-eyed woman's pleasure. Instead, the man sends the coach on its way by smacking the hind of one of the horses. Unfortunately for the young woman just waking from her faint, she's run over by the heavy coach and crushed to death. And this all occurs before the opening titles. Man, who are these people?

We soon find out when we visit the home of wealthy local widow Selma (Rita Macedo), who is being interviewed by the captain of the local constabulary (Mario Sevilla) about the deaths of the three travellers. Since they were killed nearby, he's wondering if Selma heard anything. She claims not to have. Then again, she would say that, because despite now sporting a regular set of eyes, we can clearly see that she's the black-eyed woman who instigated the killings. The Captain notes that there have been many such killings in the area recently, and that every one of the victims was found drained of all their blood. As he speaks, Selma walks the room with her back to him and a small, self-satisfied smirk on her face, while the Captain's tone of voice and accusatory glare intimates that he suspects she is somehow involved. To that end, he makes a point of telling her that he will show no mercy when he identifies the killer. He even hands the dagger found at the scene to her and doesn't ask for it back when he departs, suggesting that he knows he's returning it to its owner. After he's gone, Selma's crippled manservant Juan (Carlos López Moctezuma), the man who actually committed the murders, wanders in and picks up the knife. "Have you prepared the room for my niece's arrival?" Selma asks. When Juan replies to the affirmative, she adds, "Tell her I won't be back till evening." Hardened horror fans should be starting to put the pieces together by now, but all is not quite as genre convention might make it seem.

The niece in question is Amelia (Rosita Arenas), who is travelling to the house with her new husband Jaime (Abel Salazar – hey, it's the Baron!) at Selma's specific request, after being told to stay away for years. On arriving at the house after a carriage ride through those spooky studio-set countryside lanes, they ask the driver to carry their luggage into the house, but no way is he going in there. "It's bad enough that I came all the way up here," he adds before proclaiming that the house is cursed. Once inside, Amelia and Jaime are shown to their room by Juan, whom Amelia judgementally calls a monster when talking about him to Jaime. Their room has a dresser, part of which is covered by a cloth that Amelia lifts to reveal a mirror with an ornate wooden frame. Here we go, I thought, and I wasn't to be disappointed, as when Amelia looks into the mirror, what she sees sends her screaming from the room and into her husband's arms. In that way movie husbands and boyfriends have of being unsupportive twerps, he suggests it was all a figment of her imagination. Later, he'll be given good reason to swallow those words.

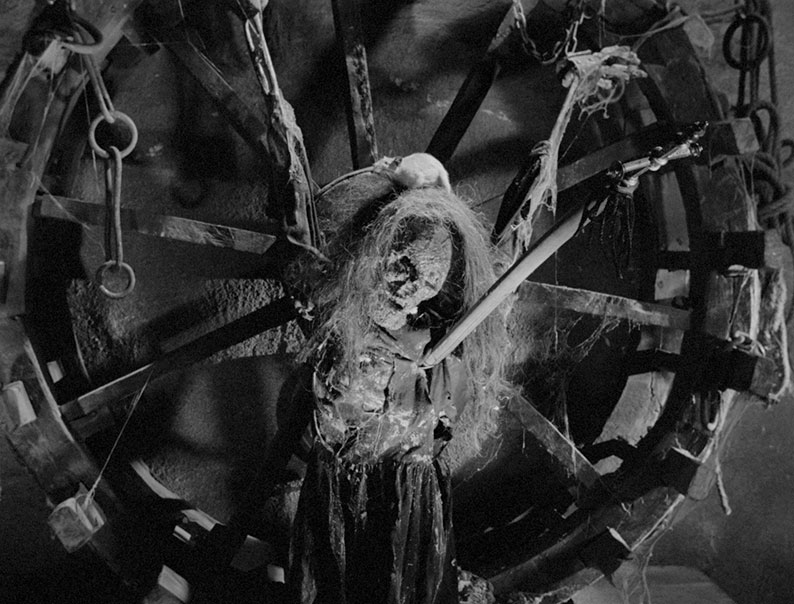

Meanwhile, down in the cellar, Selma flies in through the window and towards the camera in cloaked skeletal form, then transforms into the black-eyed woman in one of the best transitional edits I've ever seen in a horror movie. The centrepiece of a dungeon peppered with cobwebs and rats is a long-decayed corpse that is chained to a giant wheel and has a long spear protruding from its chest. When the dark eyes of Selma gaze upon it, however, an image of the woman that the body once belonged to dissolves partially into view, an apparition that clearly delights our Selma. Who is she? The clue's in the original Spanish language title, at least for anyone with even a passing knowledge of Mexican folklore. Selma refers to her as "Distinguished Lady of Darkness" and promises to return her to life again soon, an act that will apparently also make the gleeful Selma omnipotent.

A short while later she's upstairs banging out an abstract tune on the organ, the sound of which brings Amelia and Jaime downstairs. Despite being warmly greeted by her aunt, Amelia is clearly troubled by something, and we soon find out why. Apparently Selma hasn't aged a day in the many years since Amelia last saw her, but in other ways seems to be a very different person. As the two have so much to talk about, Jaime politely takes his leave, and that's when Selma reveals to Amelia the true reason for requesting her visit. And yes, it involves that creepy corpse in the cellar.

And we're still essentially on the setup here. From that extraordinary opening scene onwards, The Curse of the Crying Woman grabbed you by the throat and just doesn't let go. Although not really vampire tale as such, vampire movie codes and conventions are rife in the early scenes. Like Count Dracula, Selma lives in an old stately home of castle proportions that local people fear and refuse to enter. She dresses in black, she doesn't age, and she has a brutish assistant – a 'familiar' if you will – in the shape of the crippled Juan. When discovered, the bodies of Selma's victims have been drained of all their blood, and Selma only meets with her niece once the sun has gone down. She also casts no reflection, something she reveals to Amelia in a splendid piece of visual trickery that has been much imitated since. A connection to Tod Browning's 1931 genre-defining Dracula – or more likely, George Melford's simultaneously shot Spanish language version – is also established when Selma glides untouched through a cobweb that Amelia has to pull out of her hair. Like the mirror shot, the mechanics of the trick are just visible, but they're so well executed that I was smiling widely with admiration in both cases.

Destiny and bloodlines play a part in what proves to be a strongly female-centric tale in which it's the men who play the supporting roles, as devoted and violent manservant, as flawed would-be hero, or as hapless police chief. This really is all about Selma and what Amelia stands to inherit from her, at least if she gives in to the forces that increasingly threaten to take control of her mind and body. This internal battle hits a ballsy expressionist peak when Amelia nearly strangles an old man and her eyes subsequently turn black, and the night sky is filled with painted and projected eyes. It's one of the most striking images in a film whose cinematography – by the insanely prolific José Ortiz Ramos (he has 253 cinematography credits on IMDb!) – is consistently gorgeous.

Solid performances from Abel Salazar as Jaime, Carlos López Moctezuma as Juan, and Rosita Arenas as Amelia are nonetheless outshone at every step by Rita Macedo as Selma. Every look she gives, every sinister stare, every carefully calculated movement of her head, body and hands is a joy to watch. She creates in Selma a woman so confident of her powers and her destiny that she feels genuinely untouchable, and we all know what happens to people who behave in such a manner. Feel free to pick your own current real-world example. Rafael Baledón's smart direction is littered with inventive touches, including a dream/vision sequence peppered with shots from his earlier films that plays out in negative – even his fondness for crash-zooms works well for this material. The already otherworldly atmosphere this creates is given a further boost by the seductively discordant theremin whines of composer Gustavo César Carrión's expressive score. It all builds to a destructive and action-packed climax that wouldn't be out of place as the final scene in one of Roger Corman's Edgar Allen Poe adaptations, and while the ending may seem to play to expectation and tradition, I was left with the sneaking suspicion that the story is not over yet. Now this is how you conclude a box set of this quality.

Although the only information we have about the four transfers in this set is that they are all HD remasters supplied by Alameda Films, the quality of the results makes it clear that the films have all undergone careful restoration. All are framed 1.37:1, except for The Brainiac, which is framed 1.85:1. For the most part, they look great, with clearly defined detail, nicely graded contrast, robust black levels, and a sometimes very fine film grain. There's no errant movement of the image in frame, save for a couple of transitions in The Brainiac where the picture momentarily jumps, just a little. The Brainiac is also the only transfer with any significant dust or dirt – in the sequence just before the Baron enters a bar, there's quite a bit of it, but the transfer is otherwise one of the most handsome in the set. There's a gloomy pall that hangs over The Witch's Mirror that feels completely deliberate, giving the impression of a house that sunlight never really penetrates. All in all, an excellent set of transfers.

All four films have Linear PCM 1.0 mono Spanish language soundtracks, with the expected restrictions in the tonal range and lack of any real bass. The dialogue is always clear, however, and the music and effects come across well, something especially true of the later films, including the ear-piercing whine of the theremin on The Curse of the Crying Woman. The Black Pit of Dr. M has a whisper less clarity at the treble end of the scale than the later films, but you'd only really notice it if you were doing direct comparisons, as I was. Pleasingly, there's not a trace of background hiss or other associated wear on any of these tracks.

Also included on The Witch's Mirror, The Brainiac and The Curse of the Crying Woman are the English language tracks recorded for the films' US release. These are not in quite as good shape as the Spanish tracks – the dialogue lacks the treble-end clarity of the originals, and the tracks themselves are saddled with audible background fluff and hiss. Performance-wise, the dubs on The Brainiac and The Curse of the Crying Woman are not at all bad, but are less convincing on The Witch's Mirror, where little attempt has been made to sonically integrate the dubbed voices with the rest of the soundtrack. This is at its most comically unconvincing with the scenes involving the policemen, where this sonic misalignment combines with read-it-off-the-page performances to make them sound like they are narrating a dull documentary. Where scenes or shots were cut for the American release, the dialogue reverts back to the Spanish original and the English subtitles kick in.

And yes, optional English subtitles are provided for the Spanish language tracks. You can also activate English subtitles for the deaf and hearing impaired for the English language tracks.

THE BLACK PIT OF DR. M

Audio commentary by Abraham Castillo Flores

Film programmer, curator and Mexican horror cinema expert Abraham Castillo Flores has a voice I find so pleasant to listen to that he could read me the terms and conditions of a spreadsheet program and I would be enthralled. As someone coming to most of Mexican horror cinema anew, this proved to be a hugely educational experience, opening my eyes to films and filmmakers I'm now keen to see make their way to UK Blu-ray. Flores discusses the possible origins of the story, the history of spiritualism in Mexico, the actors, the director, producer Alfredo Ripstein, production designer Gunther Gerszo, editor Charles Kimball, composer Gustavo César Carrión, and screenwriter Ramón Obón. He also notes that while most critics cite a Dali influence on the nightclub scene, for him the paintings of Giorgio de Chirico would be a better fit. As it happens, I agree – it's the Dali designed sequence in Spellbound rather than anything he painted that I was most reminded of. A superb commentary that made me appreciate the film even more.

Daniel Birman Ripstein: Preserving a Legacy (19:19)

Producer Daniel Birman Ripstein, whose credits include The Crime of Padre Amaro (El crimen del padre Amaro, 2002), Perfect Obedience (Obediencia perfecta, 2014) and 7:19 (2016), looks at the history of Mexico's celebrated Alameda Films, and the considerable contribution made to cinema and film preservation by his grandfather, legendary producer and company founder Alfredo Ripstein. This proves compelling and enlightening stuff, and is nicely illustrated with film extracts, on-set photos, home movies, and every incarnation of the front-of-film animated Alameda logo. There's a fun anecdote about sharing a room with his father whilst attending film festivals, and it's hard not to warm to a man that Ripstein assures us loved his chocolate and candy and would liberally share his stash of it with the cast and crew of his films.

Eduardo de la Vega Alfaro: Black Pit of Dr. Méndez (26:02)

Academic and author of Fernando Méndez, 1908–1966, Eduardo de la Vega Alfaro, delivers a useful look at the career of the director of The Black Pit of Dr. M. There's a lot of detail here, from Méndez's childhood in a richly cinephile family to this, the last of four horror titles that Alfaro regards as his masterpieces. Clips from some of the key films have been included, and everything I've now heard and seen from his 1957 El vampire makes me really hope it's being lined up for a future Indicator box set.

Theatrical Trailer (3:07)

"A horror show your nerves might not be able to take," we are assured by a trailer that delivers a couple of whopping spoilers and doesn't really make the best of the material it has at its disposal. The most dusty and sonically fluffy of the trailers in this set, but the picture has been impressively stabilised in frame nonetheless.

Image Gallery

41 screens featuring largely ace quality monochrome production stills, lobby cards, a promotional piece for a screening on the "Transylvania's TV Station T.E.R.R.O.R.," newspaper ads, and posters.

THE WITCH'S MIRROR

Audio Commentary with David Wilt

Film historian and Mexican cinema specialist David Wilt takes a thoughtful look at the content, style, themes and recurring motifs of The Witch's Mirror. The influence of Alfred Hitchcock's Rebecca (1940) and Spellbound (1945) on the first half is noted, as is Georges Franju's Eyes Without a Face (1960), Robert Wiene's The Hands of Orlac (1924), and Robert Florey's The Beast With Five Fingers (1946) on the latter. Details are provided on the actors, producer Abel Salazar (who also has a lead role in two of the films here), screenwriters Alfredo Ruanova and Carlos E. Taboada, and director Chano Urueta, another dual contributor to the films in this set. Wilt also shares a brief history of the use of heart surgery footage in Mexican films, which I definitely did not see coming.

Rosita Arenas at Mexico Maleficarum (13:08)

A recording of an on-stage interview with Rosita Arenas, the lead actress of The Witch's Mirror and The Curse of the Crying Woman, conducted by Abraham Castillo Flores at the Academy Museum of Motion Pictures on 7 October 2022, following a screening of the first of those two films. It's conducted in Spanish with Flores translating on the fly, which does tend to prompt concise answers to his questions. The only even close to lengthy anecdote – about how Arenas and Abel Salazar became a couple – is broken up into bite-sized pieces to ease the process of translation. Regardless, this is still a worthy and interesting inclusion, with Arenas recalling her concerns about doing a scene involving fire, how precise Urueta was about what he wanted from an actor, her retirement from acting to raise a family, and her later return to play a role in the hugely popular TV historical soap opera, Senda de gloria.

Mondo Macabro: 'Mexican Horror Movies' (24:34)

An episode of the 2001 British TV series Mondo Macabro, written, produced and directed by Pete Tombs and Andy Starke, with narration by Penelope McGhie. It's built around interviews with Director General of the Mexican Cultural Institute Ignacio Duran, and writer and Mexican cinema specialist David Wilt, he of the commentary track detailed above. It's a potted history, sure, but still acts as a useful introduction to 1950s and 60s Mexican horror, as well as the Lucha Libre masked wrestling movies and the films featuring El Santo in particular. Tantalising clips from several films are included, actor-producer Abel Salazar and directors Fernando Méndez, Chano Urueta and Juan Lopez Moctezuma are highlighted, and Duran intriguingly describes El vampire as "an involuntary masterpiece." I have to see that film! Duan also perceptively notes, "No-one took these films seriously, obviously. Now, retrospectively, they have many things that are very interesting. But it's only after an analysis of the film through a different perspective that you can see that."

Theatrical Trailer (3:29)

Spoilers galore pester an otherwise lively Mexican trailer that's keen to show you a little bit of everything the film has to offer, and which claims it to be "the most chilling story ever brought to the screen."

Image Gallery

20 screens of promotional stills, lobby cards, posters, and press book pages.

THE BRAINIAC

Audio Commentary with Keith J Rainville

From Parts Unknown publisher and screenwriter of the animated film Los campeones de la Lucha Libre, Keith J Rainville, comes to the defence of The Brainiac with an enthusiasm that will doubtless bemuse anyone who regards it as schlock. Even though I enjoyed the hell out of the film, I occasionally found myself at odds with his comments. Yet as someone who has defended his share of maligned movies in his time, I still salute the unbridled affection he clearly has for this one. As you would hope, there's plenty of information on director Chano Urueta and his cast, which includes some famous names from Mexican filmmaking in supporting roles, as well as the film's insanely short shooting schedule and its limited release. Mexican genre movies of the period get plenty of coverage, and while he does initially champion seemingly every element, Rainville nails part of the film's appeal when he describes the brain-swallowing scene as a "bizarre bridge too far," and a sequence that "moves the film from almost childlike silliness to jaw-dropping casual cannibalism." A fun and informative listen.

Eduardo de la Vega Alfaro: ¡Qué viva Chano! (23:00)

Academic and author Eduardo de la Vega Alfaro returns to look at the life and career of The Brainiac director Chano Urueta, a child of parents with diverse beliefs – one a devout catholic, the other a committed Marxist – whose extended family included several notable Mexican luminaries of the day. He charts Urueta's journey into the film industry, first as an actor playing a young Pancho Villa, then working with the great Sergei Eisenstein on a project that was sadly never completed, and later as one of the country's key horror directors. He amusingly describes The Brainiac as being "at the top of the most bizarre films the Mexican film industry has ever produced," and a film that only Chano would take the risk to put on the big screen, partly because, in Alfaro's words, "He did not give a shit." The news that the director spent his retirement hanging round the studio, drinking tequila, smoking marijuana, and reminiscing with the like of John Huston only made me like him even more.

Theatrical Trailer (3:46)

A fun trailer for a fun film, one that's not shy of showing its monster and includes every kiss that the Baron dishes out to the women he hypnotises and subsequently kills. Unsurprisingly dramatic narration assures us that this is "a fascinating story, full of emotion" and "a most violent work of suspense."

Image Gallery

33 screens of black-and-white production stills and lobby cards, variations of two posters with different production still inserts, a gorgeous monochrome American ad that's plastered with lines like "SEE the Living Headless Body in PERSON!" and "She was beautiful, desirable, and not altogether human…" There are also some newspaper ads announcing screenings of the film – including one for a "4-feature Terrorthon" that tantalisingly teams it with The Curse of the Crying Woman, Castle of Evil and Blood Feast – and a couple of full colour posters featuring the Baron in alien monster form.

Fotonovela

Oh wow, what a find this is! Basically, a comic book version of the film whose frames have been primarily created using photos treated to look more like drawings, plus a few frames that genuinely appear to have been drawn from scratch. The dialogue is presented in speech bubbles, which are translated into English on the right-hand side of the screen. I thought this was brilliant.

THE CURSE OF THE CRYING WOMAN

Audio commentary with Morena de Fuego

Latin-American horror specialist Valeria Villegas Lindvall, aka Morena de Fuego, takes a seriously deep dive into the text and subtext of The Curse of the Crying Woman, as well as providing the expected info on the actors, cinematographer José Ortiz Ramos, score composer Gustavo César Carrión, and director Rafael Baledón. If you're someone who has a weed up your behind about gender politics and discussions on female empowerment you're in for a rough ride here (and frankly you deserve it), as de Fuego really sinks her teeth into the subject as it relates to this movie and explores it at considerable length. This does lead to some slight thematic repetition, but the arguments made are fascinating and absolutely relevant to the characters and narrative. Bava's Black Sunday is again identified as a key influence, similarities are noted to the plotting of Brainiac, and there's even an interesting deconstruction of the sequence that plays out in negative. The release and distribution are also explored, and entrepreneurial American distributor K Gordon Murray gets some coverage, not for the first time in the special features here.

Julissa de Llano Macedo & Cecilia Fuentes Macedo: The Daughters of La Llorona (25:36)

The two daughters of actor Rita Macedo – Julissa and the younger Cecilia – remember growing up with a mother that both describe as imposing, with Cecilia adding that she was "a crazy woman" whom she dearly loved and wouldn't have swapped for anyone. Julissa makes some useful contributions here, but there's no question that Cecilia is the star of the show. I quickly found myself warming immensely to her bone-dry delivery, her sly wit and her sometimes startling frankness. This is particularly true of her mother's suicide and the actions she took when she learned that her ashes had been placed in the family crypt next those of a mother she hated. I'll not spoil the surprises by revealing any more about that here, but it does shine a new light on a comment she makes at the start, when she says of The Curse of the Crying Woman, "Mum was pregnant with me in that film. I think that's why I am so dark." The story of Cecelia's initially abortive attempts to finish and publish Rosita's autobiography is also a story and a half, and told with characteristic wit. I enjoyed this immensely.

Eduardo de la Vega Alfaro: Daydreams and Nightmares (17:43)

Eduardo de la Vega Alfaro returns for his third and final contribution to this set with a look at the career of The Curse of the Crying Woman director Rafael Baledón, from his early days as a film extra to the 90+ films and TV series he directed. He's a little more guarded in his praise of Crying Woman than he was of the likes of The Black Pit of Dr. M, noting that it "has its very good moments" and "good ambience and atmosphere." He seems to prefer the director's 1959 El hombre y el monstruo [The Man and the Monster], whose imagery he claims even appears in his own nightmares.

Theatrical Trailer (4:12)

This niftily edited original Mexican trailer is driven along at a dizzying pace by the urgent voice of a narrator, who tells a few small fibs about the content for dramatic effect. It includes shots from just about every action driven sequence in the film, and a couple of untreated shots from the vision that plays in negative in the feature itself.

Image Gallery

24 screens of beautiful black-and-white production stills, a single lobby card, four variations on a poster (each with a different photo insert), two press book pages, a ticket from a drive-in theatre screening of the movie where it was double billed with The Brainiac (a seriously cool inclusion), and a second, more traditional poster.

Also included is a handsomely presented and illustrated Book (at 100 pages, no way can you call it a booklet), which features credits for all four films and a range of fine essays and other supplementary material. Kicking things off is a six-chapter examination of the key genre films produced by Abel Salazar – plus the one film in this set that wasn't – by researcher, teacher, film critic and book editor José Luis Ortega Torres. This makes for an excellent introduction to these films and the Mexican genre cinema of the period – the footnotes alone occupy two pages. Next up, programmer, curator and genre film enthusiast Abraham Castillo Flores shines an appreciative light on the four films in this set, and notes that it's about time those who made these movies got the attention they deserve. Film historian, writer and lecturer David Wilt provides a welcome look at how these films were handled in the US by the likes of K Gordon Murray and Jerry Warren, with coverage of their sale to American TV and later appearance on various home entertainment media. After this, we have an edited extract from the 2005 essay Importation/Mexploitation, or, How a Crime-Fighting, Vampire-Slaying Mexican Wrestler Almost Found Himself in an Italian Sword-and-Sandals Epic by Andrew Syder and Dolores Tierney. The title may be exhausting but the content is strong, being a thoughtful look at this fruitful period for Mexican genre cinema and how the films were handled by US distributors. Rounding things off is a reprint of an obituary of Abel Salazar, written by David Wilt and published the December 1995 edition of Monthly Film Bulletin.

What can I say? A brilliant, eye-opening set that has me gagging to see more Mexican horror films of the period, especially Fernando Méndez's El Vampiro and its sequels, though Eduardo de la Vega Alfaro's comments about El hombre y el monstruo has made sure that one's on my must-see list too. I had such a great time with this set that I almost forgot I was also meant to be reviewing it, hence my delay in getting this possibly overlong piece completed. For horror fans, I cannot recommend this release highly enough, and it's already in pole position as my favourite Blu-ray box set of the year.

|