|

I’m always impressed when a modern film opens in an unexpected manner. I’m genuinely knocked sideways when one from the mid-1930s does likewise, given that the templates drawn up back then have been recycled so often since. Take the 1934 Mexican film, El fantasma del convento, aka The Phantom of the Monastery (there’ll be more on this English language title below). Eduardo (Carlos Villatoro), his wife Cristina (Marta Ruel), and Eduardo’s good friend Alfonso are hiking in a mountain region a few miles from their home when they lose their way. As night falls, Eduardo misses his step and falls into a ravine, and is left hanging onto a protruding tree root, a plight from which he is rescued by Alfonso. Nothing unusual about this you might think, but I should mention before going on that much of this is pure speculation on my part, as the film actually begins with Eduardo hanging from the tree root and calling out to Alfonso for help, while the camera moves twitchily around as if in the hands of a documentary crew that is trying to locate the source of his desperate shouts. The accident is not shown, and no clear explanations are offered as to why this these people are in the mountains at night. I, for one, was instantly intrigued. It gets better.

With the temperature falling and nowhere to adequately shelter, Alfonso suggests they seek out the area’s old and abandoned monastery and spend the night there. Eduardo immediately dismisses the idea. “They say strange things happen there,” he claims, something the cheery Alfonso dismisses as “local folktales.” Given that both men are in a horror movie, which of them do you think is going to be proved correct before the night is out? With the cold starting to bite, Cristina sides with Alfonso (more on that in a second), to which Eduardo responds by reminding them that they are lost and thus do not know how to get to the monastery anyway. It’s then that a voice from the darkness announces sombrely, “I know the way.” The speaker is revealed to be a tall, black-clad, and expressionless individual who stares straight ahead when he speaks and is accompanied by a silent Great Dane named Shadow. “I can guide you to the monastery,” he tells them with funereal gloom and sets off on his journey, advising them to follow him or face the unspecified perils of the night. Eduardo is firmly against the idea, but Cristina and Alfonso are all for it if it means having finding shelter, so off they all trot.

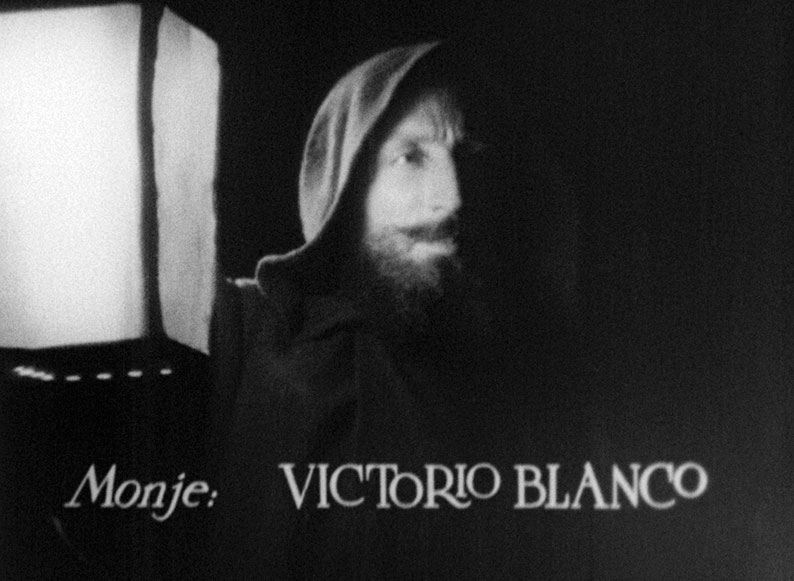

As they approach the monastery, Eduardo continues to look worried while the more upbeat Alfonso suggests that they might be in for a fun night. This prompts agreement from Cristina and a look that suggests that she and Alfonso might just be more than just good friends. Hello… Although it is supposed to be abandoned, lights are shining in the windows of the monastery, which the stranger reveals is occupied by an order of cloistered monks that has taken a vow of silence. When they reach its doors, the stranger tells them to knock, and when they tentatively do so, he and Shadow promptly vanish. The door is eventually opened by a monk (Victorio Blanco), one who seems to have yet to take his vow of silence. He invites them in and leads them to three assigned rooms, rooms he later refers to as cells and whose beds are laid out on slabs of stone. And if that above-mentioned look had you wondering if Cristina and Alfonso are having an affair, it’s here you’ll get the confirmation you’ve been waiting for. After consulting with the still troubled Eduardo, Alfonso heads off to bed down for the night when he is quietly summoned by Cristina, who then makes it clear that she wants Alfonso to come into her room, and it doesn’t take imaginative leap to realise why. Even Alfonso is caught out by her boldness, particularly with her husband nervously resting just next door. Indeed, were it not for the approach of a silent monk that Alfonso wants to tap for something to eat, I’m convinced that Cristina would have physically hauled him into her bed and hungrily ravaged him. And remember, this is 1934.

Unlike the tragic drama leanings of its Mexican genre predecessor, La Llorona, The Phantom of the Monastery is without question a horror movie, and a first-rate one at that. The richly atmospheric opening sequence in the mountains benefits hugely from actually being shot at night, or at least a convincing studio approximation of it, surrounding the characters in a cloak of darkness and completely sells the notion that they are hopelessly lost. The stranger who guides them to the monastery has more than a whiff of Valentine Dyall crossed with John Carradine about him, and the monastery interior, with its cavernous corridors, silently walking monks, and stonily uncomfortable guest rooms, never feels like the welcoming shelter of Alphonso’s optimism. Other unsettling oddities abound: the shadow and orgasmic moans of a man who is self-flagellating when the party first arrives; a cupboard that leans forward an unstable angle, which it invisibly returns to of its own accord after being straightened; the dark shape of a bat that appears on the wall of Eduardo’s room that appears to have no physical presence; the room whose doorway is secured by a giant crucifix, from which groans of despairing pain can be heard emanating.

There’s also little to comfort the three friends when they are invited to join the monks for dinner in the middle of the night, an invitation that is ominously framed at one point as “a sacrifice.” Here, attempts by the chatty Alfonso to make conversation are cut short (vow of silence and all that), and all three are confused by the appearance of Shadow, the dog that accompanied the stranger than led them there and that the Prior (Paco Martínez) insists was born in the monastery and has never left it. It all seems very sinister, but when the dinner is disrupted by the arrival of a literal ill wind, we’re given cause to suspect that the monks might actually be combatants in a battle against a supernatural incarnation of evil. Some degree of explanation is provided in the film’s least cinematic and most thematically unambiguous scene, when the Prior – who proves to be an even more talkative breaker of the vow of silence – tells the story of Brother Rodrigo, a spiritually tortured and Satan-marked monk whose infidelity with his best friend’s wife precisely mirrors Alfonso’s relationship with Cristina, a sin that the Prior mysteriously claims is the most heinous of all. I couldn’t help but suspect that he was embellishing this story to express his disapproval at what he’d have to be half-blind not to have noticed, with the increasingly bold Cristina holding Alfonso’s hand at dinner as her distracted husband eats. In an early example of a film acknowledging its subtext within the text, Cristina makes this very supposition later when Alfonso finds her waiting for him in his room wearing the most lustful of expressions and openly encouraging him to love her. At this point, there’s not a whiff of ambiguity about what she means when she says this, but it’s also becoming clear that such licentiousness is out of character, and something even she seems aware that the monastery has triggered. It’s how Alfonso responds to her request that triggers the film’s most creepily unsettlingly scene, which kicks off when Alfonso once again approaches the room with a giant crucifix in front of the door, a door that then slowly creaks open. It’s a moment that prompted my now wound-up partner to yell at the screen, “Don’t go in there!” in a tone of voice that suggested her next words would be, “you bloody idiot!”

As well as being a more fully-fledged horror work than La Llorona, The Phantom of the Monastery is also, under the confident hand of its director and co-writer (in collaboration with Juan Bustillo Oro and Jorge Peze), Fernando de Fuentes, an even more cinematically accomplished one. This is particularly evident in Ross Fisher’s often striking monochrome cinematography, from his atmospheric lighting to his handsomely composed and purposeful framing and sometimes mobile camera (that the camera movements are a little wobbly on occasion is par for the course this early in the evolution of sound cinema). Equally impressive is de Fuentes’ own editing, which maintains fluid continuity of movement (a golden rule now that wasn’t always put into practice in early cinema), and really shines in the tension-building cross-cutting between Alfonso, Cristina and Eduardo in their respective rooms as Alfonso wrestles with a key decision about his future.

The performances of the three leads also impress, with nobody overplaying the emotions of his or her assigned role. Marta Ruel in particular proves to be a quiet scene-stealer as Cristina, whether it be the eye-popping lustful looks she throws Alfonso (who is played by her husband, Enrique del Campo), or her amused scratching of an accusatory word into the monks’ dining table while her male companions are listening intently to the Prior’s story. Fernando A. Rivero's production design is also a key factor here, a combination of constructed studio sets and location work at a Tepotzotlán monastery, which together add considerably to the film’s unsettling other-worldly atmosphere. Even the opening titles have style, notably the placement of certain vowels – particularly the letter ‘o’ – in actors’ names,* while the final scene (which I’m not about to reveal here) is one that would recycled many times in various guises by genre movies in the years to come.

Those looking to do their own research on The Phantom on the Monastery may well find that the original Mexican title of El fantasma del convento is more frequently translated to The Phantom of the Convent, and indeed was referred to under that title by Stephen Jones in the commentary on Indicator’s La Llorona Blu-ray. I can see why ‘convent’ has since been changed to ‘monastery’, as the commonly accepted meaning of the word ‘convent’ is summed up by the Cambridge Dictionary, which defines it as “a building in which nuns (= members of a female religious order) live,”** which in gender terms is the exact opposite of the establishment in which the film takes place. It’s worth noting, however, that the term ‘convent’ was once not quite so gender-specific, and is defined by the Miriam-Webster dictionary as, “local community or house of a religious order or congregation, especially: an establishment of nuns.”***

Whatever the true English title, I thought El fantasma del convent was terrific. It’s really well structured, doesn’t hammer home its underlying moral message, is beautifully shot and convincingly acted, and has scenes that can still raise goose bumps almost 90 years after it was made. The only dig I could make if pushed is a score that just occasionally seems to mismatch the mood or that goes full orchestra when a scene would have been better served by silence, but this is a frankly minor quibble. I really enjoyed this film, and had I seen it as a kid when I was still acquainting myself with the wonder of old-school horror, I have no doubt that the more adult elements would have flown over my head, but also know for a fact that it would have scared the bejesus out of me.

Deep breath. The transfer on Indicator’s Blu-ray is sourced from a 2017 restoration from a 35mm nitrate print and track negative, and a 16mm acetate composite dupe negative, by Head of the UCLA Film & Television archive, Scott MacQueen. Additional funding for the restoration was provided by The Film Foundation’s World Cinema Project and the George Lucas Family Foundation. Previous to this, the only versions seen were badly degraded and often scratched 16mm prints. Don’t be misled by the soft detail and visible imperfections of the opening credits, as this sequence contains the film’s only optical process work and is the only weak spot in an otherwise hugely impressive restoration. As soon as the action proper begins, the jump in visual quality is substantial, with an excellent level of clearly defined detail, and well-balanced contrast that nails the black levels without sucking in darker aspects of the image. Dust and dirt has been scrupulously removed and almost all of the former wear and damage has been repaired and cleaned up – there are still some small traces of more extensive injury to the source material, but they are brief and are never distracting. The image has also been impressively stabilised and is free of jitter. An excellent job.

The Linear PCM mono soundtrack does have some range restrictions, something particularly noticeable on the music score, but the dialogue is otherwise clear and easily legible for those with an understanding of Spanish. There is some intermittent background hiss and crackle, but again, I never found it annoying.

Optional English subtitles kick on by default, but you can also select English subtitles for the deaf and hearing impaired if you prefer.

A small aside those who read my review of La Llorona and recall my partner’s fondness for worn and battered prints of old horror movies. When I told her about The Phantom of the Monastery, she expressed a keen interest in seeing it, but as I put the Blu-ray disc in the drive, she asked if the print used for the transfer was damaged and peppered with scratches. “No,” I told her smilingly, quite forgetting myself, “it’s been wonderfully restored.” “Oh,” she said as her face fell into a pout of disappointment. She loved the film, but still wanted a damaged version, which she regards as creepier. This time around, we’ll have to agree to disagree.

Audio Commentary with Stephen Jones and Kim Newman

Genre writers Stephen Jones and Kim Newman follow on from their commentary on the La Llorona Blu-ray with a similarly enthusiastic appreciation of a film that – unusually – neither had seen until the arrival of this new restoration, but that both now hold in the highest regard. Indeed, when signing off, Jones remarks that as an example of early Mexican horror, “this is as good as you’re going to get,” and even labels it “a mini-masterpiece.” I’m not about to argue. Areas of discussion include the top-notch cinematography, the spooky opening scene, the central love triangle, the performances of the leads, why monks are so scary, the development of the Mexican film industry and its relationship to Hollywood horror, the disturbing make-up in a key scene, and so much more. Newman notes that it’s closer to being an art film than a horror film and none the worse for that, and of the quality acting remarks, a tad unkindly but not without good reason, “Compare these guys to David Manners [in Dracula] – he’s a plank.” If you enjoyed the film as much as I did, you should have a ball with this.

Abraham Castillo Flores: The Devil in the Detail(18:01)

Also mirroring the special features on La Llorona is a presentation by head programmer of Mexico’s Mórbido Film Festival, Abraham Castillo Flores, who here takes an enthralling look at both The Phantom of the Monastery and the career of its director, Fernando de Fuentes, a pioneering figure in Mexican cinema. A couple of key questions asked by Stephen Jones and Kim Newman (who state in their commentary that they’re also looking forward to watching this) are answered here, particularly about the inspiration for an aspect of the finale, which I can’t discuss here for obvious reasons, and whether it was shot in the studio or on location inside a genuine monastery (as it turns out, both). Flores also praises the make-up effects and Marta Roel’s performance as Cristina. An excellent extra.

Booklet

The lead essay here is a substantial piece by writer, professor and researcher, Maricruz Castro-Ricalde, who confirms some of the details about the making of the film outlined by Abraham Castillo Flores (or vice versa, depending on whether you read the booklet before watching the on-disc extras), and fills in some of the remaining gaps about the production. It’s a compelling and informative read that also examines the Mexican film industry of the day, as well as discussing the lead actors and the work of cinematographer Ross Fisher. Following this is a 1979 interview with co-screenwriter Juan Bustillo Oro from the newspaper Unomásuno, in which he talks about his work on The Phantom of the Monastery, outlining the process of turning a sketch of an idea from young Peruvian producer Jorge Pezet into a feature-length screenplay, and how he went out of his way to avoid going places that “Yankee cinema” commonly went. Next we have a 1934 production report from the Mexican trade publication Mundo cinematográfico, which unsurprisingly talks up the film with a few superlatives, after which is a piece from El cine grafico on the “magnificent and innovative advertising campaign” that had been used to publicise the film’s (then) upcoming release. There are extracts from three contemporary reviews, including one from the New York Times that concludes rather bluntly, “The acting and photography are good,” and the booklet is rounded off with a pleasingly detailed piece on the restoration by author and former director of the UCLA Film & Television Archive, Jan-Christopher Horak. Full credits for the film have also been included, and the booklet is well illustrated with promotional imagery.

I liked La Llorona a lot, but adored The Phantom of the Monastery. Captivatingly directed, smartly constructed, gorgeously shot, and impressively acted, it genuinely rivals the best of the Hollywood horrors of the day, and is the most effectively creepy film I’ve watched so far this year. When I showed it to my horror-loving partner, she was so enamoured by it that she all but demanded I give the review disc to her, then nabbed my review copy of La Llorona for good measure. Early Mexican horror is well and truly back. A superb restoration and three terrific special features make this a highly recommended release.

* Here's an example of the title text:

** https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/convent

*** https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/convent

|