| |

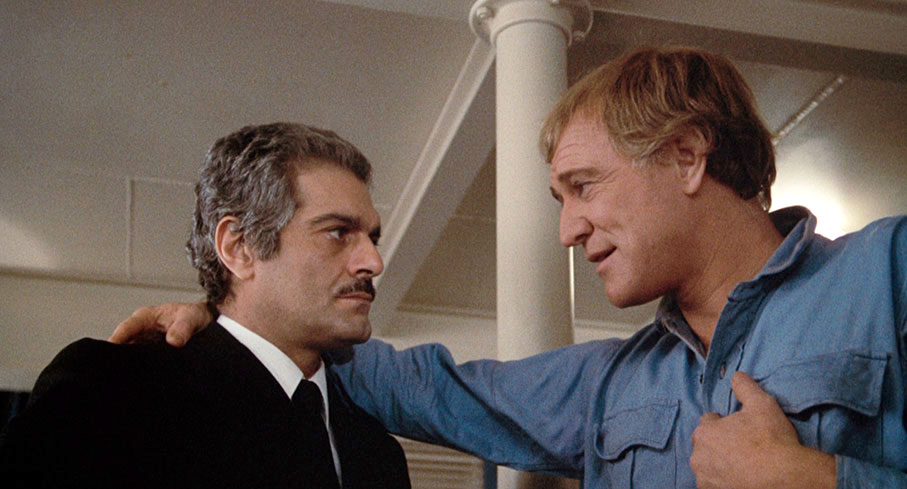

“The pace of the thriller aspect is unflagging, and the characters are unerringly drawn, from the perfect casting of Sharif as the seedy, demoralised captain, to Harris as the bomb expert (the film's research in this direction is painstaking). Without a doubt, one of the best movies of 1974.” |

| |

Time Out review of Juggernaut |

If you’ve never before encountered the 1974 Juggernaut, you could be forgiven for expecting a companion piece to Steven Spielberg’s masterly 1971 roadway pursuit TV thriller Duel. It has, after all, one of those single word titles that tend to spell out unambiguously what the principal subject matter is – think Earthquake (1974), Piranha (1978), Alien (1979), Poltergeist (1982), Ghost (1990), or even bloody Titanic (1997) for heaven’s sake. With that in mind, the fact that Juggernaut is set primarily on an ocean liner doesn’t seem to make a lot of sense. Oh, but it will, and it’s worth finding out why, and if the above-quoted review didn’t tip you off about how highly I regard this film, then buckle up, as I’m soon going to get into precisely why.

It begins at an unspecified British dockside (anecdotal evidence suggests Southampton) as a crowd of people wave to their relatives and friends on the deck of Sovereign Line cruise ship Britannic as preparations are made for its departure to New York, a celebratory event serenaded by a brass band and awash with colourful streamers. As the ship gets under way under the command of Captain Alex Brunel (Omar Sharif), effervescent Social Director Mr. Curtain (Roy Kinnear) sets about trying to engage the passengers in a variety of activities, something only a few respond to, particularly when the vessel hits rough seas. The ship, it turns out, is in the midst of a refit, and one of the casualties of this still incomplete work are a set of stabilisers that simply aren’t up to the job, and if you’ve ever been in a large boat in choppy waters you’ll be well aware of the impact this has on the delicate stomachs of the passengers. This, it turns out, will soon prove to be the least of their problems, but will nonetheless further complicate what lies ahead.

Back on dry land, Nicholas Porter (Ian Holm), the managing director of the Sovereign Line, is trying to sort breakfast for his lively kids when he receives a phone call from an unidentified, Irish-accented man, who identifies himself only as “Juggernaut” and who calmly informs him that he has placed seven explosive devises on board the Britannic, and that shortly after dawn the next day they will explode. Juggernaut tells Porter that he will provide the information that will enable his people to disarm the bombs if the “very modest” sum of £500,000 is paid (that’s equivalent to about £5 million in today’s money). Aware that Porter will instruct Captain Brunel to make a search for the devices, Juggernaut informs him up front that they are located in seven green-painted steel drums, but that the devices are fitted with a variety of booby traps and any attempt to move or tamper with them will cause them to immediately explode. By way of a demonstration of his skill and sincerity, he has also planted two smaller devices on the upper deck, which explode at the very moment he reveals this information. The incident leaves a single crew member injured and one particularly savvy passenger, American politician Corrigan (Clifton James), with questions that 3rd Officer Jim Hardy (Andrew Bradford) is forced to unconvincingly deflect by claiming the crew was just blowing one of the boilers.

Back on dry land, Porter meets with Commander Geoff Marder (Julian Glover) of the Royal Navy, government representative Hughes (John Stride), and police operation coordinator Superintendent John McCleod (Anthony Hopkins), a stoic professional who nonetheless has a personal stake in tracking Juggernaut down as soon as humanly possible as his wife and two children are on the Britannic. When Porter admits to Hughes that he intends to pay the ransom, Hughes cooly responds by telling him that it is government policy not to negotiate with terrorists, and uses the substantial government subsidies that the Sovereign Line receives as leverage to pressure the outraged Porter into reluctantly complying. With the seas too rough to evacuate the ship’s 1,200 passengers and crew, a team of bomb disposal experts led by the talented and assertively self-assured naval officer Lieutenant Commander Anthony Fallon (Richard Harris) and his good friend and second-in-command Charlie Braddock (David Hemmings) is dispatched with orders to diffuse the bombs, unaware that they are up against a man whose skill with explosive devices is easily equal to their own.

Too often Juggernaut finds itself labelled as part of the disaster movie wave of the 1970s, the template for which was unknowingly drawn up by Airport in 1970, although the genre was really kicked into high gear in 1972 with The Poseidon Adventure and hit something of a peak with The Towering Inferno and Earthquake in 1974, the same year in which Juggernaut was released. This misclassification of Juggernaut was not helped by a poster (one I like a great deal, I should note) that practically screams “Disaster Movie!” at you, and the film’s more literal alternative title, Terror on the Britannic. And then there’s the cast. If you’ve been keeping tabs on the bracketed names of the actors who play the so-far named characters, you’ll be aware that Juggernaut is something of a star-studded affair, at least looking back at it from a modern perspective. Quite aside from the already mentioned players, we have Shirley Knight, Freddie Jones, Michael Horden, Jack Watson, Ken Colley, Kenneth Cope, Simon MacCorkindale, David Purcell, Gareth Thomas and Cyril Cusack, to name but a few, and I can guarantee that fans of British film and television of the 1970s will spot a few other faces they recognise but can’t quite put a name to. On paper this certainly seem to be conforming to the disaster movie sales pitch norm of packing the cast with famous faces, but it’s worth noting that many of the performers here were not yet the recognisable names that they later became and were clearly cast because the director simply wanted the best actors he could get for the roles.

Ah yes, the director. If you’re new to Juggernaut and have read the above synopsis, you may well be surprised to learn that it was directed by Richard Lester, the man who revolutionised cinema with the Beatles films A Hard Day’s Night (1964) and Help! (1965), and cemented his reputation with the film adaptation of A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum (1966) and the downbeat romantic drama Petulia (1968). After his career took a hit following the critical and the box office failure of The Bed Sitting Room (1969) – a film I hold in high regard, I should note – Lester found himself back in considerable favour following the acclaim for and financial success of The Three Musketeers (1973), a project that was famously split into two movies to be released in consecutive years. Indeed, Lester was putting the finishing touches to what would become The Four Musketeers (1974) when he was contacted about possibly helming Juggernaut by associate producer Denis O'Dell, who was due to start shooting in four weeks but had a script he was not completely happy with and no director after two had already bailed on the project. Intrigued by the film’s premise, Lester contacted his good friend, TV scriptwriter Alan Plater, and while they retained the story structure of the original script by the film's producer Richard Alan Simmons (writing under the pseudonym Richard De Koker), they apparently rewrote every line of dialogue. Omar Sharif, Richard Harris and David Hemmings had already been cast, but Lester was otherwise free to draw on the pool of British (and in two roles, American) acting talent of the day, including talent he had worked with on previous projects.

Although known for the comic edge he brought to many of his earlier films, Petulia had shown that Lester could also make a serious and compelling drama, but he had never before attempted a thriller, let alone one on the scale of a film like Juggernaut, but boy, did he rise to the occasion. The economy of his cinematic storytelling is established in the opening scene, which – one almost floating crane shot aside – is an almost documentary record of the Britannic’s departure, where much is established without the need for introductory captions, narration, or even scene-setting dialogue. A good example of this revolves around the character of John McCleod, who is observed standing on the dockside waving goodbye to his wife and two children, and as the ship departs, he walks over to a police patrol car, where the door is held open for him by a uniformed officer, establishing in a single shot that he is a high-ranking officer of the law. Later, when the ship hits rough seas, the scale of the seasickness it triggers in the passengers is neatly captured with a single shot of meals being returned untouched and scraped into the waste disposal.

The casting is pitch-perfect, and with a single but highly appropriate exception (more on him in a minute), the performances are impressively retrained throughout, right down to the smallest of speaking roles. I’m in full agreement with Neil Sinyard in his excellent piece on the film on this very disc when he states that in his view, Richard Harris is at his This Sporting Life best as bomb disposal wizard Anthony Fallon, and I genuinely can’t overstate just how good he is here. In his introductory scene, as he and Charlie diffuse a bomb inside what looks like London’s National Gallery, he delivers his lines and works with the props in a way that feels simultaneously real and performed, the actions and attitude of a man supremely confident of his abilities and disdainful of this “pitiful little bomb” and the “enthusiastic amateur” who put it together. The on-screen chemistry between Harris and David Hemmings sells Fallon’s friendship with Charlie as authentic and long-standing in a matter of seconds, as they quip about the bomb and the upcoming job aboard the Britannic (“Ooo… I need a holiday”), and especially when they leave the scene to the almost world-weary football chant of “Fallon’s the champion!” clapping in unison in the manner that is clearly for them a familiar mantra. As they descend the steps outside, Charlie makes a waggly hand movement to suggest they grab a drink, prompting a gloriously real “Oh, yeah!” reaction from Harris, an actor who was renowned for his fondness for booze. The whole sequence last less than two minutes, but by its end I felt I already knew these two characters well enough to care about them and their crucial role in the task that lay ahead.

It's a similar story elsewhere. Just the way Anthony Hopkins momentarily falters as he waves to his wife and kids at the dockside speaks volumes about his anxiousness at their departure. His later fear for their safety is reflected in the urgent efficiency of his investigation into the identity of the bomber, while his suppressed emotional state is captured nicely by his almost offhand admission to Porter, “My wife and kids are on that ship.” From the moment he says his first words, John Stride paints Hughes as a smugly confident and instantly unlikeable minister of the crown, while Ian Holm’s authoritative delivery and suppressed fury at Hughes’ insistence that they not pay the ransom is expressive of a man being pressured to play politics with twelve hundred lives. There’s a nicely played scene when first officer Hollingsworth (Mark Burns) delivers a message about the upcoming rough seas to Captain Brunel, only for Barbara Bannister to emerge from his quarters, a recently concluded sexual liaison suggested by the Captain’s open collar and Barbara retrieving and replacing her earrings. It can initially seem as if Indian actor Roshan Seth is skirting with a racial stereotype as ship steward Azad, but in a lovely and perfectly timed reveal this turns out to be an act that he puts on for the passengers, one presumably designed to play to their narrow preconceptions of how someone of his Indian heritage would speak. As savvy American politician Corrigan, Clifton James is the perfect person to question Hardy about why the ship is sailing in circles and the cause of the demonstration explosion, then to slyly call him out on his attempts to deflect. “In my line of work,” he tells him dryly, “you have to learn how to lie with remarkable precision. You also have to know how to recognise a lie when it bites you in the ass. And I have just been bitten.”

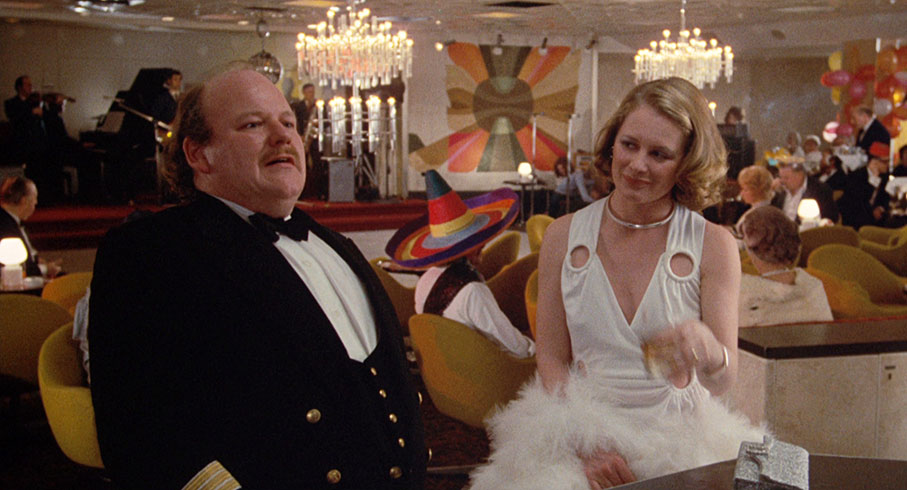

The most commonly praised performance – and the one that initially seems to kick against the restraint on display elsewhere – comes from Lester regular Roy Kinnear as Mr. Curtain, the ship’s ever-ebullient social director. It’s he who provides the clearest through-line to Lester’s earlier work, remaining superficially and infuriatingly cheerful even in the face of grim adversity, irrespective of whether his efforts are appreciated or even acknowledged. This reaches an almost wince-inducing peak once the passengers are informed of the ship’s potential fate and are reluctantly coerced into dressing up for a fancy dress ball (quite how they were convinced is another matter entirely), as Curtain tries unsuccessfully to press the depressed and distracted attendees to join him in an overenthusiastic rendition of The Gang’s All Here and emulate his demonstration of The Lambeth Walk. This is all then turned unexpectedly on its head when he finally gives up and hits the bar, where kind words are offered for his efforts by Barbara, to whom Curtain spits bitterly without turning to face her, “Don’t patronise me, darling.” Yet it’s these two who inadvertently lead the charge that lifts the rest of the passengers out of their gloom, an upbeat few minutes that is then undercut with a twist of fate that genuinely shocked me on my first viewing.

Yet without question my favourite supporting performance comes from the ever-superb Cyril Cusack as incarcerated IRA bomber Major O'Neill, whom his old adversary McCleod visits in the hope that he will reveal who is currently active in his field. I won’t reveal the content of the conversation that follows, but Cusack’s delivery is sublime, and the interaction between the two men suggests so much about their past relationship, once again without explicitly detailing anything. It’s a quietly brilliant little scene that lasts a mere 97 seconds, but is the one that made the biggest impression on me following my first viewing of the film at a late night cinema screening back in my film school days.

Lester handles the build-up with urgent efficiency, cutting between the as-yet blissfully unaware passengers, the crew as they locate and secure the barrels containing the bombs, Fallon and his team in the belly of the military aircraft transporting them to the Britannic, and the investigation being led by McCleod to identify the man who planted the devices. There’s a tensely handled action set-piece when Fallon and his crew parachute into rough seas and have to climb up rope ladders to board the ship, and once the team reach the bombs, the screws are really tightened. Of all of the jobs I would never have the nerve to do, bomb disposal would be close to the top of the list. I used to work with two ex-army bomb disposal experts, and the stories they told me of their work in the field made what hair I still had at the time stand on end, and any such scene in a film is guaranteed to have me chewing my fingernails. Powell and Pressburger’s The Small Back Room (1949) is a standard bearer here (the source novel by Nigel Balchin is also a compelling read, by the way), while in 1979 TV graced us with Danger UXB, a superb but frequently grim WWII-set series that is littered with bowel-twitchingly stressful scenes of bomb disposal.

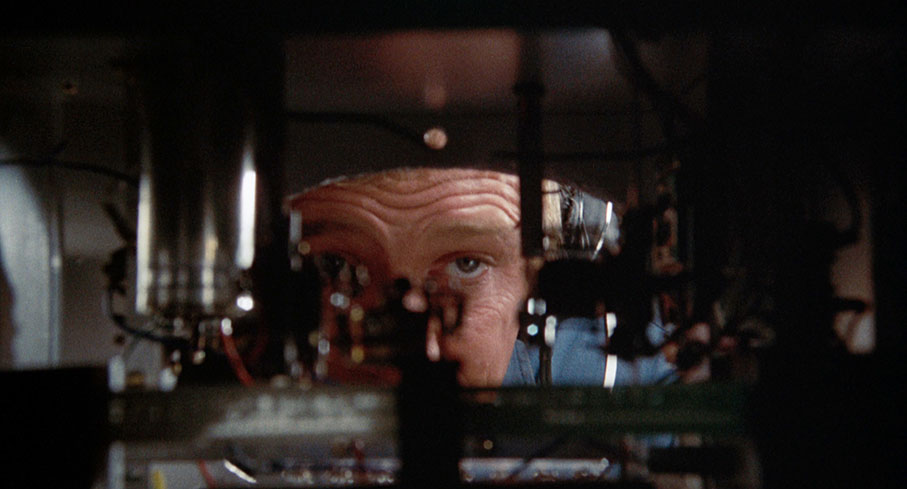

In Juggernaut, the operation to diagnose the nature of bombs and attempt to disarm them – and I’m not going to say here whether it’s successful or not – begins even before the film’s halfway mark and increasingly dominates its final third. And boy, are these scenes tense. Knowing that the devices are heavily booby-strapped means that even getting inside the barrels presents Fallon with a considerable challenge, and once a way is found, the sheer complexity of what lies within ensures that every step he and his team take could be their last. Cinematically, these scenes are immaculately handled, with cinematographer Gerry Fisher’s camera gradually closing in on Fallon’s face, eyes and hands and the intricate parts of the various mechanisms within and even outside of the barrels. Big close-ups are superbly used to this effect, ensuring that the simple act of attempting to loosen a tightly fixed screw on a barrel’s exterior will have you shifting in your seat in fear. I’m not in a position to say how realistic these various booby traps or Fallon’s actions are, but what’s crucial is that they feel completely authentic and carefully researched, ensuring that at no point does the process feel implausible of fanciful. Only the logic of a single decision made late in the day could be called into question, and I’d still put this down to a desperate and frightened man acting quickly on his instincts before thinking it through.

The air of realism that Lester brings to the drama is enhanced by the decision to film on a real boat in sometimes stormy seas (unsurprisingly, the continuity of the weather conditions does wander a little) and Gerry Fisher’s naturalistic lighting, purposeful framing, and mix of locked-down shots and handheld camera. This is then shaped into a string of tightly constructed scenes by editor Anthony Gibbs, a master of his craft who worked previously with Lester on The Knack… And How to get It (1965) and Petulia and whose credits also include Performance (1970), Walkabout (1971), Rollerball (1975), A Bridge Too Far (1977) and Dune (1984), to name but a few. His work on the sequences in which the booby traps in the bombs are slowly diagnosed and immobilised is exemplary, and the montage that plays over Juggernaut’s initial phone call to Porter, which cuts between the preparatory action being taken by the police and the unaware Britannic crew and passengers, is an object lesson in economical cinematic storytelling. There are even two occasions where Gibbs makes brilliantly expressive use of something as simple as a cross-dissolve. The first immediately follows the demonstration explosions on the Britannic and begins on a close-up of Captain Brunel’s startled face, which then seems to be turning red, only for colouration to increase in intensity until the screen is filled with this colour. This is then revealed to be an interior wall in the National Gallery when Fallon pops up into the very bottom of frame, expressionistically connecting Brunel with the man who is about to be tasked with attempting to save his ship. The second example also forms a visual connection between two related characters and occurs at the end of an on-deck conversation between Barbara and McCleod’s seasick wife Susan (Caroline Mortimer). As Susan ponders on Barbara’s words, her face seems to almost morph into the identically positioned one of her husband as he waits in the dark of a prison meeting room, lost in thought just moments before his encounter with the man he hopes will lead them to the individual who is threatening his family’s life. Straightforward transitions they may be on the surface, these two dissolves are not just artistically impressive, they bring extra layers to the characters and story. This, for me, is the filmmaking of Juggernaut in a concise nutshell.

Several viewings after my first late night encounter with Juggernaut, so many sometimes offhand moments in the film resonate with me now: McLeod’s young children David and Nancy (played by real-life brother and sister Adam and Rebecca Bridge) on deck with a book about ships given to David by his mother, and David casually noting that a flag indicates that the Britannic is carrying explosives; David’s response to the Fallon’s crew parachuting into the sea dressed in wetsuits and their struggle to get on board, “He looks like my Action Man. It is Action Man!” to which his sister cooly responds, “It isn’t”; the mockingly cynical “Great” delivered by a wetsuit-dressed Fallon when welcomed on board the Britannic by Hardy; Charlie muttering, “Don’t even know the man and he’s trying to kill me,” after his screwdriver slips, which prompts the response from Fallon, “Haven’t I told you about death? It's nature’s way of telling you you’re in the wrong job”; Curtain desperately faking an upbeat demeanour and cheering on a room full of potentially doomed passengers with “Are we downhearted?” only for Barbara to respond with a weary smile, “Well, just a little”; Fallon irritably telling Marder to “Shut up, Jeff,” when he needs silence to concentrate, then, after a pause, revealingly adding, “Don’t go too far, Jeff;” Fallon indicating a stain on the wall caused by him angrily hurling a whisky bottle and saying to Brunel, "You can generally tell see I've been"; and so many more.

Lester’s direction is impeccable throughout, in the tightness and economy of his scene construction, his direction of the consistently excellent cast, his seemingly offhand but always purposeful character detail, and – and oh, how important this proves to be – in his decision to restrict Ken Thorne’s score to just a couple of scenes and allow all of the bomb defusal sequences to unfold without a note of musical accompaniment. There’s no question in my mind, Juggernaut is a masterful and too-often overlooked gem of 1970s cinema, one whose plot and characters cannily reflect the turmoil of this period of British socio-political history, and for this humble viewer it remains to this day one of the finest, richest, and tensest thrillers of that illustrious decade.

The 1080p presentation of the film in its original 1.85:1 aspect ratio appears to be from an HD master supplied by MGM and the results are unwaveringly strong. The image is sharp, with crisply defined detail and an attractive filmic texture, and the contrast is nicely graded, with black levels rock solid and generally good shadow detail. The colour palette is intentionally naturalistic and that’s nicely reproduced here, and when brighter colours do make an appearance – the striking reds of the gallery wall or the infrared lighting during the disarmement process – they are vividly rendered. The image is also clean of damage and there are only a very few tiny remaining dust spots, A fine film grain visible.

The original mono soundtrack is presented here as Linear PCM 2.0, and while it lacks the tonal breadth of later Dolby stereo tracks, the dialogue, effects and ambient sound are always clear, and there is no trace of background hiss or wear to disrupt the tension during the nail-chewing quiet of the bomb dismantling scenes. One thing I will note is that the louder sounds, specifically the two or three intended to make us jump – which include a moment when the Captain’s address to the passengers is sharply disrupted by David and Nancy dropping the contents of a pick-up sticks game onto a tabletop – do not seem as loud here as I remember them being in the cinema. But then again, that was a long time ago…

Optional English subtitles for the hearing impaired are included, and I spotted no obvious errors. I did notice that the character of naval officer Marder’s first name is spelt Jeff here as opposed to the Geoff of the film’s IMDb page. Which is correct is anybody’s guess, as while his first name is said several times in the film, it’s never seen written down and he’s simply credited as Commander Marder in the closing credit roll.

Audio Commentary by Melanie Williams & James Leggott

Film and Television Studies lecturer at the University of East Anglia, Melanie Williams, and Associate Professor of Film and Television Studies at Northumbria University. James Leggott, deliver an informative and sometimes perceptive commentary on Juggernaut and its making. They examine the content of the film in relation to the turbulent socio-political situation in Britain of the day, praise the work of editor Anthony Gibbs and cinematographer Gerry Fisher, discuss the contribution of individual actors and screenwriter Alan Plater, note the parallels to the Titanic story, and speculate that one of the passengers may be a Juggernaut accomplice (not sure I buy this one, but the suggestion is intriguing nonetheless). They provide info on the filming and the experience of some of the actors, comment on the importance of the sound design (oh, absolutely), discuss the gender politics of the film, praise the handling individual sequences (Williams admits that she’s a sucker for bomb defusal scenes, something we absolutely have in common), and put a knowing smile on my face when they remark how effective key scenes must have been on the big screen. Oh, you have no idea.

Down With the Ship – Sheldon Hall on Juggernaut (20:17)

Academic and film historian Sheldon Hall – whose recent book Armchair Cinema: A History of Feature Films on British Television 1929-1981 was reviewed on this site by Gary Couzens – looks at Juggernaut in relation to the 70s disaster movie wave that it was released slap-bang in the midst of. He outlines how the film differentiates itself from the likes of The Towering Inferno and Earthquake, notes that it exchanges disaster movie spectacle for suspense, comments on the very British response of the characters to impending disaster, and cannily observes that the scale of the film is progressively narrowed, right down to the macro close-ups of booby traps and coloured wires. Another very fine companion to the film.

All Hands on Deck – Neil Sinyard on Juggernaut (27:33)

Film writer Neil Sinyard, whose many books include The Films of Richard Lester, is so in sync with my view of the film that I began to wonder if we were separated at birth, particularly when he describes the cast as flawless, praises Richard Harris’s performance as one of the finest of his career, highlights the excellence of Cyril Cusack’s cameo, and calls Juggernaut one the best films about early 1970s Britain. He details how the Lester came on board just four weeks before shooting was due to start, delves into how the film also works as a socio-political allegory and a story about hierarchies and power, and notes how Fallon never loses respect for Juggernaut, seeing the complexity of his bombs almost as a work of art. There’s plenty more of real interest here. An excellent inclusion.

Stills Gallery (19:58)

A lengthy rolling gallery, set to Ken Thorne’s score for the film, of promotional stills, cast portraits, posters and poster artwork.

Original Theatrical Trailer (2:54)

“The greatest sea adventure of all time,” is the rather reckless claim (“all time” includes the future, so how would they know?) made by the typically serious-voiced 1970s narrator of this otherwise well-assembled trailer, one that technically includes a few spoilers that are edited in a way that ensures they register instead only as brief tasters for the tension to come.

Booklet

Following the main credits, there is an engaging and perceptive essay on the film by film critic and historian Richard Combs, who pertinently asks, “Is it a social allegory? A disaster movie? A political thriller?” The general opinion appears to be all three. Media lecturer at the University of Hull, Laura Mayne, then looks at the film in the context of its director’s career, highlighting the editing, the use of sound, the mix of static shots and handheld camerawork, and the film’s reception.

What, another overlong review for a favourite film so soon after my coverage of Seven Samurai? Well, here’s the thing. If a pile of review discs lands on my doormat, and one of them is a film you’ve been aching to see released on UK Blu-ray for many years, that’s going to inevitably jump to the front of the queue. Juggernaut is a film that for me hasn’t significantly dated since I first saw it late one Saturday night on a huge cinema screen a few decades ago. The script is smartly structured and witty, the acting is superb, the cinematography and editing are top-notch, and Lester’s direction is first-rate throughout, economical in its storytelling and character building, and building tension to an almost unbearable degree during the scenes in which Fallon and his team attempt to diffuse Juggernaut’s bombs. The film’s presentation on Eureka’s Blu-ray is first-class, and the special features really compliment the film. Highly recommended.

|