| "Whatever you do, see Seven Samurai." |

| Life changing advice from a father to his son |

The year was 1979 and I was halfway through my three-year course at film school, and the passion for cinema that had pushed me down this route was about to be launched in a whole new direction. In the college holidays, I’d landed a job at Waterloo in South London, a mere ten minutes’ walk from the National Film Theatre (which has since been rebranded as the BFI Southbank). It seemed too good an opportunity for a film devotee such as myself to ignore, so I joined the NFT and began attending as many screenings as I could afford. I began on what was back then safe ground for someone raised on American and British movies, the result of being restricted to whatever was playing at local cinemas or on the comically small black-and-white TV that I had in my college digs. I thus initially gravitated to watching personal favourites like The Private Life of Sherlock Holmes and acknowledged classics like Citizen Kane on the big screen, while the first curated season I attended to was devoted to the films of American director Anthony Mann. Then, during one of these holiday breaks when I was staying with my parents, the latest NFT programme arrived, brimming with details of the following month’s films. As ever, it was chock full of titles both familiar and exotic-sounding, movies I’d never even heard of, let alone seen. My father, from whom I inherited my love of film, was interested in what they were showing. He glanced through the brochure and, on handing it back to me, said just six words that were to forever change my viewing habits and my perception of just what constituted great cinema:

"Whatever you do, see Seven Samurai."

I was familiar with the title from the film books I had started to collect and read, and also aware that the film itself was held in extremely high regard, but my father's words carried considerably more weight. Such recommendations were rare, but always proved to be worthwhile – previous titles had included Double Indemnity, West Side Story, The Godfather and A Clockwork Orange, all of which quickly became favourite movies. But he was, by nature, not a devotee of foreign language films – it's not that he had a problem with them, it's just that, like most of us in those pre-home video days, his access and exposure to them was limited, as indeed was my own. Yet here he now was, recommending that I see a Japanese film, and one that that the booklet assured me was over three hours long. At that age, I wasn't even aware that there were films that ran for that length, and certainly couldn't imagine sitting through one.

This was, as it turns out, a great time to experience Seven Samurai [Shichinin no samurai] for the first time. Having been heavily cut to 158 minutes for its international release and further trimmed to 141 minutes in some European territories, it had then only recently been restored to approximately three-and-a-quarter hours, 15 minutes shy of its complete original version (I wish I could be more exact about the running time, but it wasn’t included on the handout given at the screening, which I still have it). Unbeknown to me, for reasons I cannot explain or excuse now, this restored print was first screened in the UK by the BBC as part of a World Cinema season. Having somehow missed that (my father clearly hadn’t), I was thus excited to discover that this same print was the one that the NFT would be screening. I thus bought my ticket for what I seem to remember was a Saturday or Sunday afternoon screening, then trotted up to London and took my seat in the auditorium of NFT1. I emerged into the foyer after convinced that the fabric of time had somehow been distorted. My watch assured me that I'd been sitting in the cinema for three-and-a-quarter hours, but I knew in my heart of hearts that it had really only been about forty minutes. I've seen the film many times since and the same thing always happens – time just disappears. I don't know another film that achieves this so invisibly. But then, there isn't another film on Earth quite like Seven Samurai.

I'm not going to pussyfoot around here – as far as I'm concerned, Seven Samurai is nothing short of perfect cinema, and I'm making that judgement on the basis of 20-something viewings over a period of 45 years, and the most recent viewing really was as thrilling as the first, especially given the quality of this new 4K restoration (I’ll get into the specifics of that below). I'm assuming that the vast majority of you reading this have at the very least heard of the film and that a sizeable proportion of you have seen it at least once. If you haven't, then put it at the top of your upcoming new year resolutions, and I mean the very top. Stuff the diet, forget about decorating the house or flat, and remember my father's wise words. For the very few of you who do not know the film I have no words of admonishment, just a genuine envy for the magical first viewing that lies ahead.

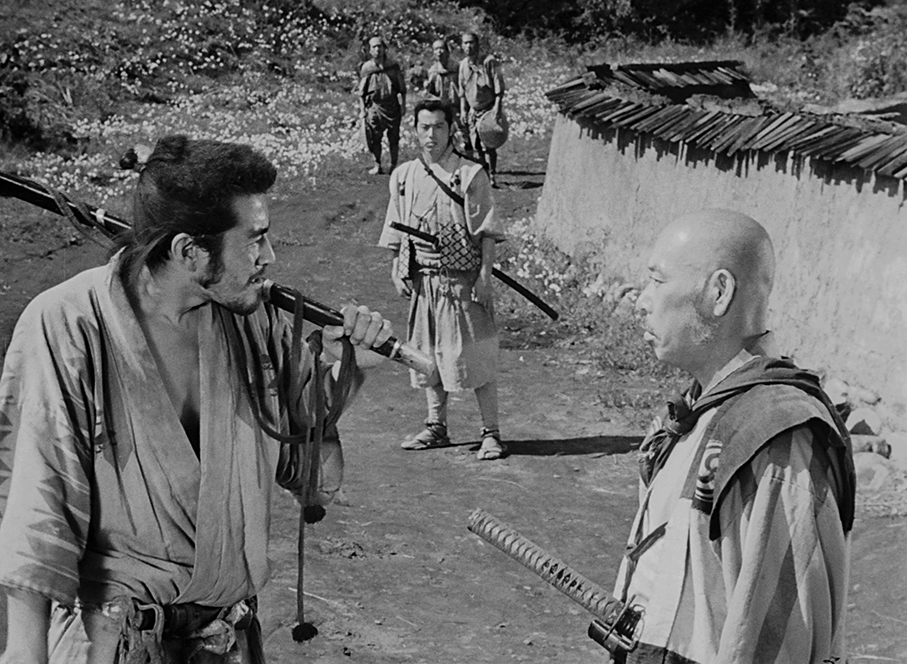

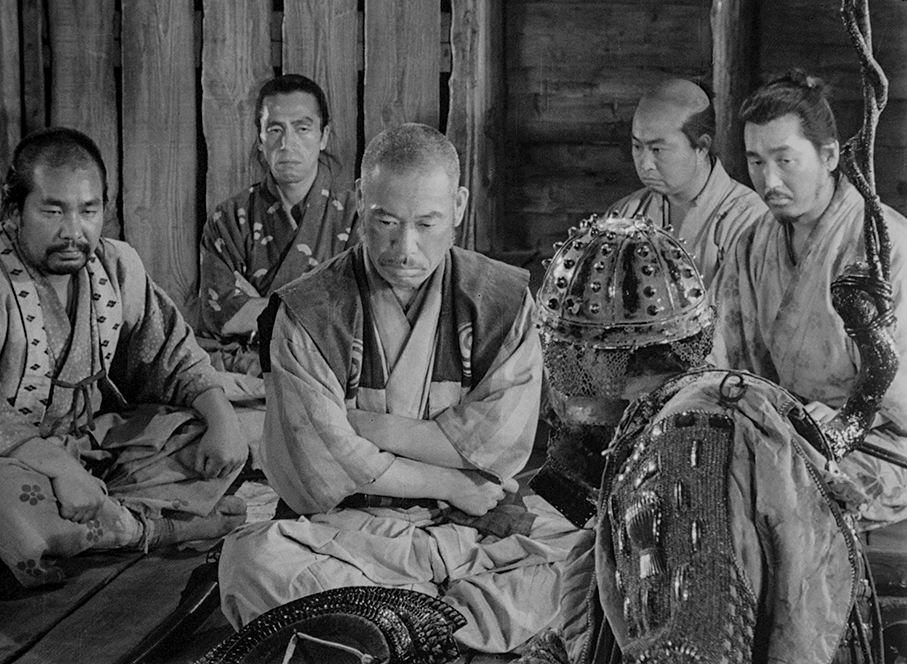

The plot has been reworked and recycled many times since and is deceptively straightforward in concept. In 16th century feudal Japan, the residents of a farming village being threatened by bandits decide to hire a group of samurai to protect them and their annual harvest. The problem is that they have no money with which to pay the samurai and can only offer food and lodging, hardly an attractive prospect for members of a proud warrior class. It takes just a couple of minutes of film time to set this up, something internationally celebrated director Kurosawa Akira does with blinding economy, and in seemingly no time four of the farmers, led by the anxious Rikichi (Tsuchiya Yoshio), set off to a nearby town in search of potential protectors. The recruitment of the samurai occupies a substantial proportion of the film's first third and is a constant delight, with each of the samurai introduced in a manner that is both memorable and reflective of their distinct personalities. Rarely have I seen such a range of characters so beautifully defined with such economy and speed, and every one of these scenes is packed with a wealth of inventive and entertaining detail.

The casting is sublime and crucial to the creation of such a range of vivid and memorable characters. Kurosawa favourites Shimura Takashi and Mifune Toshirō are perfect fits as the calmly knowledgeable and authoritative Kambei and the brash, excitable, wannabe samurai Kikuchiyo. But they are matched all the way by a supporting cast of talented actors who inhabit their roles so completely that it's genuinely hard to imagine them dressed in modern clothing. The youthful novice Katsushirō (Kimura Isao), the good natured Gorōbei (Inaba Yoshio), the ever-optimistic Shichirōji (Katō Daisuke), the cheerful Heihachi (Chiaki Minoru), and the introspective master swordsman Kyūzō (Miyaguchi Seiji) are all played to perfection, and I haven't even touched on the farmers and distinctively drawn bit-part players. It's also fair to say that this was the film that convinced me once and for all that if you're going to watch a film shot in a language in which you are not fluent then you should always seek out a subtitled rather than a dubbed version. So much of what makes the characters in Seven Samurai live so vividly on screen is down to how the dialogue is delivered, whether it be Katsushirō's overenthusiasm, Kyūzō's matter-of-fact minimalism ("Killed two," he states simply after returning from a one-man raid on the enemy camp before immediately settling down for a nap), or Kikuchiyo's boastful arrogance and, in two of the most justifiably famous scenes, tearful fury.

We are an hour into the film before the samurai reach the village that they have agreed to defend, and it still feels as if we're in the opening stages. Here, the blend of action, drama and humour is precisely balanced, and the cast of characters expands considerably to include a love interest for Katsushirō in the shape of pretty village girl Shino (Tsushima Keiko), a band of giggling children to form an audience for Kikuchiyo's clowning, and an ageing grandmother who only leaves her home after a bandit is captured, but you'll remember her long after the film concludes. The character interaction, of which there is great deal, also increases our understanding of, and attachment to, the individual samurai, but also to the farmers and their families, a frightened community forced to recruit men that they would normally fear, and, as we later discover, mercilessly prey on.

To reveal further plot details would take up time that would be better spent watching the film itself. Its length allows a depth of development that gives rise to narrative arcs within narrative arcs, and a level of character depth and interaction that no other action film has ever achieved. Indeed, so well developed are the dramatic and character elements that I have trouble, despite its breathless action sequences, actually categorising Seven Samurai as an action film at all, primarily because the is so much more to it than that. No argument here, Die Hard is a top-notch action movie, but its characters, as has become the norm for the genre, are little more than creatively and engagingly drawn cartoons. In Seven Samurai they are all recognisably human, drawn from history and legend but with the strengths, failings and everyday concerns of the common individual. And while the action scenes, when they come, are blisteringly handled, they comprise only a small portion of the film’s 207-minute run time. The rest of the film is devoted to telling the story, drawing the characters and charting their evolution, and exploring both the kinship and the conflicts that definite the complex and sometimes fractious relationship between the frightened farmers and the samurai who are willing to put their lives on the line to defend them.

The script, by Kurosawa and his Ikiru collaborators Hashimoto Shinobu and Oguni Hideo, is a marvel of construction, with every scene – and I do mean every scene – beautifully handled by its director, whose artistic and technical skills as a master of cinema are consistently evident in the expressive framing, the emotive closeups, the immaculately composed and blocked wides, and the often mobile camera of Nakai Asaichi’s superb monochrome cinematography. Kurosawa’s willingness to challenge and even break the then accepted norms of cinematic scene construction is also on show in his editing (Kurosawa was his own editor here), notably his purposeful disregard for the 180-degree rule, his decision to stage some key moments off-screen, and his use of jump-cuts (in a brief but brilliantly edited pan) to suggest the seven samurai are collectively a single warrior. The Academy frame is put to consistently arresting use, with characters repeatedly foregrounded in moments of high emotion, deep focus shots in which the reactions of those the individual in question is temporarily distanced from also register.

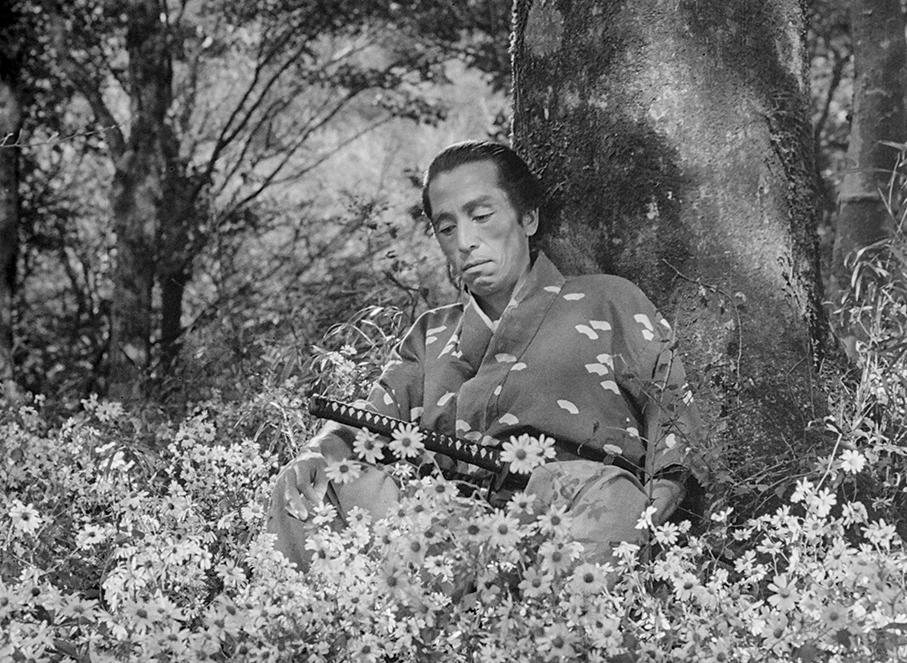

The narrative surprises and rewards are timed to perfection, often layered to produce multiple hits from a single scene or story strand. A personal favourite occurs during the recruitment expedition (I'm avoiding specifics here so newcomers can experience the impact for themselves) when the farmer's rice supply is stolen and they are left with nothing with which to feed the samurai that they are trying to recruit. This leads to a moment of desperate, pathetic sadness, which is then shattered by a gloriously unexpected gesture of solidarity, all of which links directly back to an earlier scene of deep humiliation for the farmers that is transformed by the words, "I accept your sacrifice." Oh man, I get goosebumps just thinking about it. And there are so many such moments, running the full gamut from the intimate to the epic: Kikuchiyo's overenthusiastic participation in the village harvest; Katsushirō lying down in a bed of glowing white flowers; the battle flag that has Kikuchiyo represented by a triangle instead of a circle because, "You're so special"; Heihachi pausing his enthusiastic wood cutting to cautiously move his sword out of reach of the watching Gorobei; Kyūzō's Zen-like fascination with a single flower before suddenly leaping into action; farmer Yohei's despairing response to just about everything; the kidnapped (and we presume raped) farmer's wife who would rather die than face her husband again; the way Kambei's eyes rest on Kyūzō when all others are on his duel opponent; Kikuchiyo furiously lambasting his fellow samurai for their destructive behaviour and in the process revealing a crucial truth about his background, then later holding the baby of a slaughtered family and weeping, "This baby...it's me!" ...and there are at least a hundred more. To top it all, there's the final battle, an astonishing sequence that is steadily and excitingly built up to and fought in Kurosawa's beloved rainfall. It’s an action scene that has rightly earned its place as one of the finest in film history, a conflict staged on a grand scale that is as tragic as it is breathtaking, as sad as it is thrilling.

To be honest, I could write about Seven Samurai until there are enough words to fill a book so large that it would shatter all of the bones in your foot if you dropped it, but there are other reviews to write and I’m coming late to a party that began over half-a-century ago. This is a film that has been so widely analysed and written about that anything I might add (and, I'd venture, everything I've already written) has very likely already been said many by others before me, and probably in more detail and with greater eloquence (you’ll find plenty in the rich supplementary material that accompanies this release). The danger for newcomers approaching such a weight of critical analysis is that they can be frightened off by the expectations that it builds, which may seem to suggest a film they will admire for its craftsmanship rather than one they will enjoy, but such apprehension really is unfounded here. Seven Samurai is indeed magnificent cinema, but it is also stupendous entertainment – it tells a riveting story, is crammed with wonderful character interplay, plays successfully with just about every emotion you care to experience, and is consistent cinematic dynamite. The script is superb, the performances divine, the cinematography and editing both dynamic and purposeful, and the music score one of the most memorable in cinema history. Dramatically compelling throughout, the film is also rich in metaphor and subtext, commenting on Japanese society both past and (then) present and carrying worthwhile lessons for humanity as a whole. The action, when it comes, is still breathtaking today, with the swordplay breaking from the kabuki-inspired theatricality of earlier chanbara works in favour of a gritty realism that changed its portrayal in film forever.

The film has also been credited as one of the first to be based around the now common trope of a diverse collection of individuals being recruited to work together for a common goal, and the film’s central story has been reworked many times in the years that followed with varying degrees of success. Most will know that the film was remade in Hollywood as The Magnificent Seven, which despite its status as a western classic is a film I’ve never really warmed to. It's a very well-made and enigmatically cast work, to be sure, but I've yet to sit through it without being constantly reminded how much richer and more entertaining each of the scenes and characters in Kurosawa's original are. Then there's Roger Corman's 1980 Battle Beyond the Stars, a tacky, low budget science fiction remake that nonetheless wears its cheese on its sleeve in a way that is actually quite endearing. And let us not forget Miike Takashi’s 2010 13 Assassins [Jûsannin no Shikaku], which although a remake of 1963 film of the same name directed by Kudo Eiichi, borrows liberally from Seven Samurai in its structure, characters and the content of specific scenes, and Tsui Hark's Seven Swords [Chat Gim], which even had the same number of warriros recruited. Perhaps the most intriguing of the remakes is the 2004 anime series Samurai 7, which sticks to the story and retains the names and the traits of the characters of Kurosawa’s original, while the longer running time allows screenwriter Tomioka Atsuhiro and director Takizawa Toshifumi to expand inventively on both aspects.

I've always had trouble narrowing my favourite films down to anything below about three hundred titles, but know for a fact that if I was forced to choose just ten to spend the rest of my viewing days with, then Seven Samurai would definitely be one of them. As I noted above, for me it’s one of those rare films that achieves cinematic perfection, and is more deserving of the term masterpiece than almost any other such classified film that comes readily to mind.

Ah, how our standards and expectations have changed with the evolution of the tech that we use to watch movies at home on. Home cinema enthusiasts tend to scoff at it now, but it’s hard to over-emphasise how big a deal the arrival of DVD was for those of us for whom laserdiscs and their associated players were an unaffordable dream. After years of collecting and recording films on VHS tape, to have a format in which films were presented in their original aspect ratio, and the image was clear and would not start to wear out and accrue damage after just a couple of plays, was a glorious thing.

Of course, not all DVD releases were of exactly pristine quality, but over in America, the fine people at Criterion took what they had been putting into practice for some time on their laserdisc releases and replicated it for this far more affordable new format. That said, even they were often at the mercy of the film materials that they were sometimes forced to work with, and back then digital restoration was still in its infancy. Right now, I have four separate disc versions of Seven Samurai, and one of the very first DVDs that I purchased was the Criterion release of the film, and to put this in historical context, Seven Samurai was only the distributor’s second DVD release after Jean Renoir’s La grande illusion. Luckily for this early adopter of the format, this was before Criterion began regionally encoding its titles and before I was forced to pay over the odds for a multi-region DVD player. The transfer was on that disc was certainly decent enough for the day and a real improvement over my VHS copy, but the source print was covered in scratches, dust spots and other sundry signs of wear, much of which remained even after the restoration. If I remember right – and feel free to correct me if not – Toho was not happy with the inclusion of a restoration demo on the Criterion disc because it highlighted the state into which the film had been allowed to deteriorate, which in turn reflected badly on the studio that funded the film and which still owned the rights.

This disc was eventually retired thanks to the arrival in 2006 of a handsome new three-disc special edition DVD, also from Criterion, which absolutely wiped the floor with the previous release. A substantial collection of special features had been added – two of the best of have also been included with this latest release – but the jewel here was the far more substantially restored transfer, which at the time I remember describing as stunning, which for a DVD release of a substantially worn film from half a century earlier I’d still argue that it was. The signs of wear were still there, but the improvements in digital restoration software had allowed the team at Criterion to remove much of the previous blight and push the rest of it back so that it was no longer anything like as intrusive. The difference between this new disc and its predecessor was almost night and day.

In 2010, Criterion upgraded this release to HD on the then relatively new Blu-ray format, but Blu-ray regional coding was more technically difficult to bypass than it its DVD equivalent, and I did not then have the necessary dosh for a multi-region Blu-ray player. Fortunately for me, four years later the film made its way to UK Blu-ray as part of the BFI’s Akira Kurosawa: The Samurai Collection, a box set that also included Throne of Blood (1957), The Hidden Fortress (1958), Yojimbo (1961) and Sanjuro (1962). By this point, the high bar for HD restorations of older films had been set insanely high by the gorgeous transfers on Eureka’s Blu-ray releases of F.W. Murnau’s City Girl (1930) and Fritz Lang’s M (1931), and for this increasingly demanding viewer, Seven Samurai on BFI Blu-ray look good rather than great, with detail definitely a crisper than it had been on DVD but an image that never popped in the manner that I had hoped it would.

Which brings me, finally, to this new UHD release of the film, also from the BFI, and if you’ve been waiting for as many years as I have to see the film looking as glorious as it has always deserved to do, well, that wait is definitely over. Quite simply, Seven Samurai looks better here than I’ve ever seen it or frankly ever expected to see it, and it seems oh so appropriate that I was introduced to the film by the very organisation responsible for this absolute belter of a UHD release. I say UHD as the film is presented in 4K on a single UHD disc, but as the special features were all delivered in 1080p, they – with two exceptions – have been collected together on a separate Blu-ray disc, freeing up space on the UHD to allow this long film to maximise the available bitrate. The transfer itself was sourced from a new 4K restoration by Toho, and the jump in definition over previous Blu-ray and especially DVD releases is substantial and immediately apparent. This really hits home on the facial close-ups, where individual hairs on heads and beards can be counted and even the pores on the skin of the actors are often clearly visible but is also clear on a variety of textures, including costumes. For the first time I was able to clearly see the tears in Kambei’s eyes following Kikuchio’s furiously impassioned speech about farmers and samurai. As is sometimes the way with restorations of older films, a few of the wide shots seem just slightly softer than the rest of the material, but even these are a serious step up from the earlier transfers. Once again, faint signs of the former wear are still visible, but only just, having been further cleaned up and pushed back to the point where you really have to look to spot them, and for much of the time the image is spotless. Honestly, the best material here is nothing short of astonishing. The contrast is, for the most part, beautifully graded with rock solid black levels, and while there are scenes when those deep blacks give the contrast a punchy feel, the Dolby Vision HDR ensures that the principal shadow detail is retained. As you would expect, a fine film grain is visible, and the image sits rock solidly in frame.

The original Japanese soundtrack is presented here in DTS-HD Master Audio 1.0 mono, and while the tonal range is unsurprisingly restricted, clarity is never an issue and there are no signs of damage, background hiss or fluff to contend with.

Optional English subtitles are activated by default, but can be switched off if your Japanese is far better than mine.

It should also be noted that the run time includes the original midway intermission.

UHD

Audio Commentary with Adrian Martin

Aside from his slight mispronunciation of Kurosawa’s name, Australian writer and critic Adrian Martin does a frankly amazing job here, proclaiming up front that he is not interested in providing biographical details about the actors or the film’s production, both of which he points out can be easily found elsewhere. Instead he examines the film as “a masterclass in cinema and the craft and art of filmmaking,” and the fact that he is able to authoritatively and perceptively speak on this subject for an unbroken three-and-a-half hours is a testament to just how well he appreciates and understands this extraordinary film. Areas covered include Kurosawa’s skill with editing and mise-en-scène, the historical basis for the masterless samurai depicted in the film, the purpose and execution of individual shots, the art direction, the role that the sexual consummation of lovers plays in the story, the changing critical fortunes of the film, the many wide shots featuring crowds of onlookers, and so much more. He quotes from various writings including co-screenwriter Hashimoto Sinobu’s book Compound Cinematics, notes that the seven title characters are all component parts of the ideal samurai, points out that the film is structured like a musical symphony, suggests that George Miller has learned more from Kurosawa than any of his American contemporaries, and gets a nod of approval from me when he opines that The Magnificent Seven was not a patch on what Kurosawa achieved. I’m just scratching the surface of this excellent commentary.

Gallery (6:10)

A rolling gallery of posters (not the lovely framed one that I have hanging on my living room wall, I should note – thanks again, Camus!), costume sketches and production stills.

BLU-RAY

Akira Kurosawa: It is Wonderful to Create [Kurosawa Akira: Tsukuru to iu koto wa subarashii] (49:08)

A 2002 documentary on the making of Seven Samurai, made as part of the Toho Masterworks series and narrated by actor Yui Masayuki, who worked with Kurosawa on Kagemusha (1980), Ran (1985) and Dreams (1990), and who describes Seven Samurai as “the greatest masterpiece in the history of Japanese cinema.” The film is built around interviews with several Kurosawa collaborators, many of whom worked on Seven Samurai including co-screenwriter Hashimoto Shinobu, assistant director Horikawa Hiromichi, assistant lighting technician Kaneko Mitsuo, actor Tsuchiya Yoshio (who plays farmer Rikichi), set decorator Hamamura Kōichi, script supervisor Nogami Teruyo, assistant art director Yoshirō Muraki, and sound effects editor Minawa Ichirō. Also contributing is music director Ikebe Shinichirō, who worked with Kurosawa on Kagemusha and Dreams. It’s a fascinating journey covered in impressive detail that includes some archive behind-the-scenes film footage and photos of the Seven Samurai shoot, and a look at some of the original documents relating to the production, including Kurosawa’s notebook and Nogami’s note-peppered copy of the script. The first-hand accounts of the interviewees are always of interest and often revealing: Hashimoto outlines the two films he wrote for Kurosawa that didn’t get made but eventually led them to Seven Samurai; Kaneko tells of the director’s insistence that the lighting should make actress Tsushima Keiko’s eyes sparkle; Muraki recalls the problems that arose when filming the burning barn scene; Minaro reveals how they created the sound effects for falls into the mud and excitedly neighing horses; and Tsuchiya tells an alarming story about how things nearly went badly wrong during the shooting of the raid on the bandit camp. An excellent inclusion carried over from the Criterion release.

Philip Kemp selected scenes commentary (20:15)

Film critic and writer Philip Kemp provides a commentary on a few selected scenes. Some of this is scene-specific, the rest is more generally related to the production, as when he provides some historical context for the Japan in which the film is set, including the caste system of the day, and what happened to samurai who lost their jobs. He usefully explains why the crowd gathered around Kambei in his introductory scene are so shocked when he cuts off his topknot, reads a quote from Kurosawa outlining how much he learned working as an assistant director to Yamamoto Kajirō, and talks about the master/pupil relationship in Kurosawa’s films and Hayasaka Fumio’s memorable score. He also highlights the purposeful brilliance of the editing of the panning shots of all seven samurai running that are cut together to make them all seem as if they are one being. Another very fine and welcome inclusion, though Kemp does mistakenly state at one point that Mifune Toshirō played the lead character in Kobayashi Masaki’s 1962 Seppuku (aka Harakiri), a role that was actually played by Nakadai Tatsuya – Mifune is not in the film at all.

The Art of Akira Kurosawa (48:35)

Carried over from the BFI’s Akira Kurosawa: The Samurai Collection box set is this compelling and informative interview with Asian cinema expert Tony Rayns, which pleasingly covers different ground to Adrian Martin’s commentary. Rayns discusses how Kurosawa transformed the chanbara film by challenging the genre’s established norms, how a ban on left-leaning films in postwar Japan saw leftist filmmakers smuggling their political messages into swordplay movies instead, and how Kurosawa’s sudden success following the Golden Lion award win for Rashomon at the 1951 Venice Film Festival really irked the older generation of directors, particularly Mizoguchi Kenji. Rayns details the ups and downs of Kurosawa’s career, recalls first seeing Seven Samurai on UK TV in its cut-down form, places the film in the context of post-war Japan, and recalls a conversation he had with Kurosawa in which the director became defensive and irritated when asked about western cinema influences on his films. There’s much more here. Another excellent companion to the film.

My Life in Cinema (115:58)

A video interview with Kurosawa Akira conducted by Ai no korīda [In the Realm of the Senses] and Merry Christmas Mr. Lawrence director Ōshima Nagisa, shot for the Director's Guild of Japan in 1993 and also featured on the Criterion DVD, Blu-ray and UHD releases. Kurosawa here talks in great detail about his early life and film career, and I do mean in great detail – this is a near two-hour interview covered by just two cameras with the occasional slow zoom or cut to close-up providing the only visual variety. Playing as a more relaxed take on the BBC's Face-to-Face interview format, this is nonetheless an invaluable and compelling record, being probably the most comprehensive interview with Kurosawa committed to either tape or film, and crammed with interesting information about his life, his work and his opinions. His notebook entry, which was made when he was still an assistant director, that Japanese films needed to be "more dynamic," is a particularly telling comment in light of the work he later became famous for.

Original Theatrical Trailer (4:10)

Original theatrical trailer? Well, yes and no, this being the Japanese trailer for the Toho rerelease of the film in its uncut form. I have to presume that it was aimed squarely at an audience that had already seen the film in one cut or another because it kicks off with the narrator revealing how many of the samurai are left alive at the end and is assembled almost exclusively from footage of the climactic battle. If you’ve not seen the film, steer clear of this until afterwards.

2024 Restoration Trailer (1:36)

Now you’re talking. An expertly assembled trailer for the new 4K restoration rerelease of the Seven Samurai that seductively captures the essence of the film’s blend of drama, action and humour. I’d want to rush out and see it immediately after watching this.

Book

First up in this packed 76-page beauty is a new piece by film historian and critic Philip Kemp, the opening paragraph of which alone would have me wanting to see the film. He provides some historical context for the characters and story, outlines the qualities of several key characters, and briefly discusses Kurosawa’s location shooting, as well as the film’s release and international success.

Next up is a substantial piece by Tony Rayns, whom I salute for also respecting the Japanese naming convention of surname first and who traces Kurosawa’s journey to Seven Samurai via the two scripts he wrote with Hashimoto Shinobu and especially his screenplay for the 1952 Araki Mataemon: Ketto Kagiya no Tsuji. Directed by Mori Issei, the resulting film was not a success, but interestingly featured four of the actors who would play title characters in Seven Samurai. Rayns’ commentary on the film itself is well worth reading, and I did like Kurosawa’s response when asked to describe his film, when he called it, “as rich as a buttered steak topped with grilled eel.” I’m salivating.

Writer, film critic and filmmaker Cristina Álvarez López opts to examine the intertextuality of Seven Samurai, drawing links to the American westerns made by directors such as John Ford, Howard Hawks, Budd Boetticher and Anthony Mann. She also looks at Kurosawa’s influence on filmmakers as diverse as Sergio Leone, Kitano Takeshi, Jim Jarmusch, Jean-Pierre Melville and Quentin Tarantino, and even finds a link between Kurosawa and the work of Josef von Sternberg and Ingmar Bergman. It all makes for intriguing reading.

The focus of an essay by Charlie Brigden, a writer and critic who specialises in film music, is composer Hayasaka Fumio and his long working relationship with Kurosawa, and Brigden deconstructs his score for Seven Samurai in fascinating detail.

UK-based film critic, author and filmmaker specialising in Japanese cinema, and co-founder of the excellent Midnight Eye website, Jasper Sharp, traces the critical fortunes of the film from its release to its present-day status as a widely acclaimed classic. This is followed by a glowing 1955 review by Gavin Lambert for Monthly Film Bulletin, who describes Kurosawa as “a technician whose brilliance is unsurpassed by any director in the contemporary cinema.”

Japan based film critic James-Masaki Ryan has personal recollections of first encountering the film on VHS tape whilst visiting his uncle in New York and how it impacted him, before turning his attention to the film itself, Kurosawa’s filmmaking, and the importance of the work of his collaborators. Perhaps unsurprisingly, he also respects the Japanese naming convention.

Also from 1955 is the Sight and Sound review by none other than Direct Cinema pioneer Tony Richardson, who – surprisingly – has reservations about Mifune Toshirō’s animated performance, but otherwise has nothing but enthusiastic praise for the film.

Credits for the film and the special features have been included.

Oh, how I dreamed of this day, even before I was even vaguely aware that the medium of delivery here would even exist. My relationship with Seven Samurai is a long standing-one that began with that revelatory NFT screening 45 years ago and has continued ever since through off-air VHS recordings, DVD, Blu-ray, and now UHD disc releases, and this is the film that first kicked off my now passionate love affair with Japan and all aspects of Japanese culture. As for this new BFI UHD edition, I have no problem whatsoever suggesting that – at least for now – it should be considered the definitive home media release of the film, at least if you’re based in the UK. If you’re in the US, the Criterion UHD doubtless has a similarly strong transfer and includes two of the best special features from this release, Akira Kurosawa: It Is Wonderful to Create and My Life in Cinema, as well as two commentaries and a documentary on how samurai traditions helped to shape the film that are specific to that release. Personally, I’m as happy as I could be with the BFI’s release, which boasts a beautiful transfer from a remarkable restoration and a superb collection of special features. If you love this film, indeed if you love cinema, then this release is going to fill you with joy. As such, it gets our very highest recommendation.

As a footnote, it’s worth recalling the content of that BFI Blu-ray box set of Kurosawa samurai films mentioned above. Might the other titles within also be getting the UHD restoration treatment from the BFI in the future? Could be. Earlier this month, the BFI announced its first quarter 2025 disc releases, which include a UHD double-bill of Yojimbo and Sanjuro, news that had me bouncing around the room with joy. That just leaves Throne of Blood and The Hidden Fortress, of which there is no news yet, but we can surely hope.

All of the Japanese in this review respect the Japanese convention of family name first.

|