|

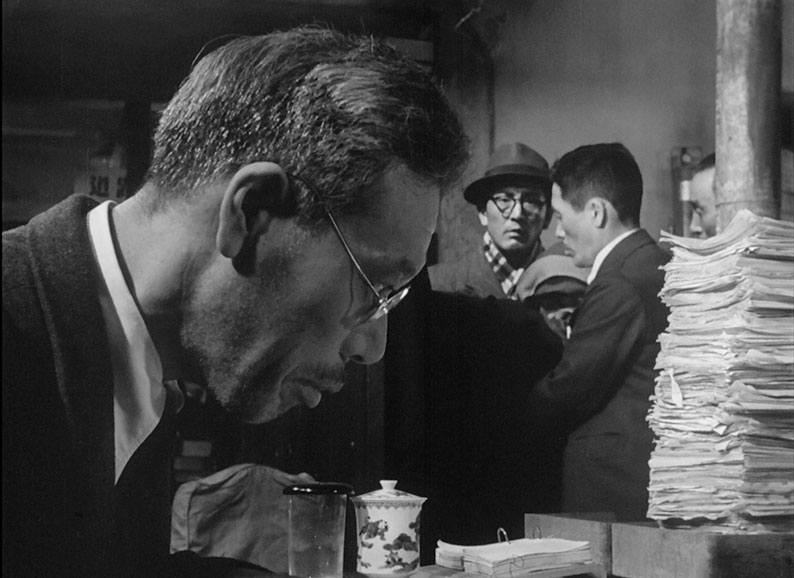

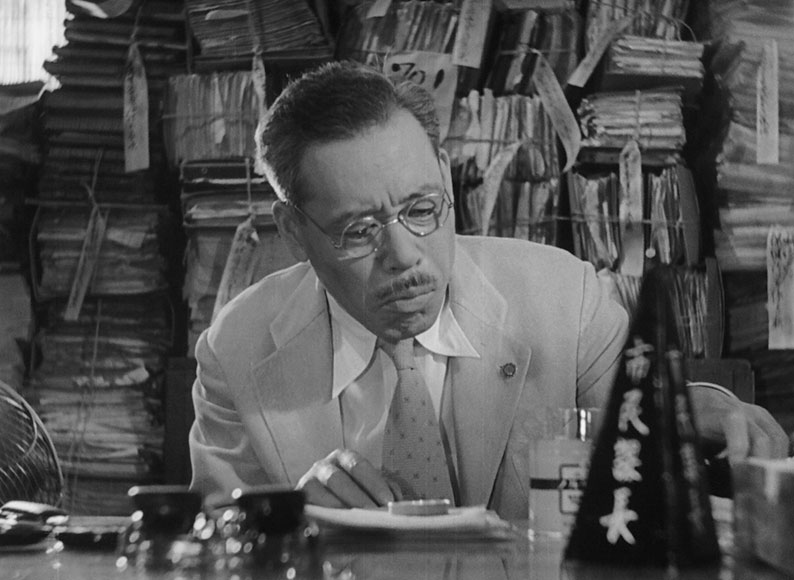

Tokyo, the early 1950s. Kanji Watanabe (Takashi Shimura) has worked in the public works department for nearly thirty years. A widower, he lives with his son Mitsuko (Nobuo Kaneko) and daughter-in-law Kazue (Kyoko Seki). Meanwhile, a group of parents are campaigning to have a cesspool drained so that a children’s playground can be built are passed from pillar to post and back again. Then Watanabe learns that he has incurable stomach cancer. He does not tell his son, nor indeed almost anyone else. He loses himself in nightlife and drink, but that isn’t the solution. Watanabe becomes involved with a young subordinate, Toyo Odagiri (Miki Odagiri), and the campaign for the playground and this way finds a purpose in the short time he has left...

Ikiru (which translates as To Live, though this is a foreign-language film usually known by its original title in the UK) was Akira Kurosawa’s fourteenth feature film, made in 1952. It was quickly recognised as one of his finest films, though on its somewhat belated original UK release in 1959, it was a step aside from the historical films, often with samurai settings, that Kurosawa was known for at the time. It remains one of his great works. I will flag up some spoilers for both this film and the British remake, Living (2022), in due course.

The first of those historical films was Rashōmon (1950), his twelfth feature, which not only established Kurosawa’s reputation in the West but was a breakthrough film for Japanese cinema as a whole when it won the Golden Lion at the Venice Film Festival. In his acceptance speech, Kurosawa thanked the audience but suggested how much better he could do with a contemporary subject. Ikiru was the result, with The Idiot (Hakuchi, 1951) an ill-fated adaptation of Dostoevsky, originally four and a quarter hours long, being made in between. The writing credit for Ikiru is shared by Kurosawa, Shinobu Hashimoto and Hideo Oguni. I will go into more detail about the division of duties after the spoiler flag, but the original idea was Kurosawa’s (more of a pitch: “A man has seventy-five days to live”), partly inspired by Tolstoy’s novella The Death of Ivan Ilyich. From that, Kurosawa and Hashimoto wrote the script. Oguni did no actual writing, but his job was to comment on and make suggestions for what was written, and the film’s distinctive structure was his input, of which more later.

The film removes any suspense it might have had from its opening shot. A third-person narrator speaks over an X-ray photograph of Watanabe’s stomach. “Our hero” has cancer, not curable, but he does not know it yet, nor that he has a limited time left to live. This narrator makes appearances on the soundtrack off and on during the first ninety minutes or so of his nearly two-and-a-half-hour film, and his last contribution is to introduce the film’s major structural shift. The narration, when it appears, is ironic, distancing us a little from Watanabe, precluding any tendency to sentimentality. Why is this man, this nondescript bureaucrat, who has been doing his job without missing a day for nearly thirty years, the hero of this film, or of any film? He is not a man who is living. With not much of his life left, even if he isn’t aware of that yet, he will learn to.

You could imagine other Japanese directors of the time making a film from this subject matter. As this is to some extent a family drama – though Watanabe’s relationship with his son and daughter-in-law is not the easiest – you could perhaps see a story like this made by Yasujirō Ozu, for example. Stylistically, though, Ikiru is rather different. While not choreographing intricate camera arabesques, Kurosawa does move his camera more than Ozu would have done at this stage of his career, though as that was more than “almost never”, that’s not saying a lot. Also, Kurosawa transitions between scenes by means of wipes – notably in an early section portraying the convoluted ways of dealing with bureaucracy, where he wipes between sixteen shots in a row – rather than the straight cuts to “pillow shots” that Ozu favoured. Some of Kurosawa’s techniques are quite subtle. For quite some time, light never reflects in Watanabe’s eyes, an indication of how he is the walking dead (“The Mummy” as Toyo tells him is his nickname in the office). Then, as Watanabe sings “The Gondola Song”, a sad and affecting setpiece in itself, the light finally reflects in his eyes. He returns to life, and his relations with Toyo, and his support for the building of the playground are his expressions of this.

It’s at this point I discuss the structure of the film, and if you have not seen the film before (or the remake), be aware there will be spoilers from this point onwards. To avoid them, please jump ahead to the “sound and vision” section.

Ikiru is a film of two parts, not two halves but two thirds and one third. After 92 minutes of this 143-minute film, the narrator announces that five months after the scene we have just watched, Watanabe dies. On the screen is his funeral photograph, and we are at his wake, which has followed the opening of the playground Watanabe had campaigned for. Watanabe was not given any public credit for it, though. His co-workers congregate, alcohol is drunk, and they try to figure out what had caused this change from jobsworth to advocate. None of them had been aware that Watanabe was dying – he had told none of them, not even Mitsuo. As the wake goes on, we see some flashbacks, some of them giving different views of Watanabe, Rashōmon-style. They are inspired to do similar good works when they return to their jobs, but you wonder to what extent they will do. This isn’t a sentimental film, and to some extent a pessimistic one. At the end, we are left with a policeman, who witnessed Watanabe on a child’s swing, rocking back and forth as snow falls on him. It’s with this epiphany that we leave the man.

Ikiru opened in Japan on 9 October 1952. It won two local Best Film awards, from Kinema Jumpo and Mainichi Film Concours, also winning Best Screenplay and Best Sound Recording at the latter. It played in competition at Berlin in 1954, winning the Special Prize of the Senate of Berlin. (The Golden Bear that year was won by David Lean’s Hobson’s Choice.) It did not receive a UK cinema release until 1959. It originally played British cinemas in a version shortened to 130 minutes, the cuts being made to the wake sequence. I haven’t seen that version, which is obsolete anyway as the full version has been released on VHS, DVD and now Blu-ray, plus has had British television showings, which is how I first saw the film. Reviewing the film in the August 1959 Monthly Film Bulletin (reproduced in the booklet of this edition), John Gillett refers to the cuts, which he says are relatively unimportant but “the slow rhythm of the drinking ritual loses some of its cumulative effect”. Gillett had clearly seen the full version previously, possibly at Berlin.

By the time Ikiru was released, Rashōmon, the film Kurosawa did next, Seven Samurai (Shichinin no samurai, 1954), and the one two after that, Throne of Blood (Kumonosu-jō) had all seen the light of British projector lamps. These were historical/samurai films. So for someone who did not go to film festivals and relied on what British distributors put before them in cinemas which showed foreign-language films, the change of subject matter, setting and style that Ikiru demonstrated may have been all the more startling. (The other films Kurosawa made in this period – I Live in Fear (Ikimono no kiroku, 1955), The Lower Depths (Donzoku, 1957) and The Hidden Fortress (Kakushi tonde no san akunin, 1958) – had UK releases later, as indeed did his earlier pre-Rashōmon films.) Takashi Shimura, who gives one of the great performances in any of Kurosawa’s films, was nominated for a BAFTA Award as Best Foreign Actor, losing to Jack Lemmon in Some Like It Hot.

In 2022, there was released Living, directed by Oliver Hermanus from a screenplay by Kazuo Ishiguro, who was a longtime admirer of Kurosawa’s film. Bill Nighy plays the central role, now called Williams. The film relocates the story to London though instead of a black and white contemporary setting it is in colour (and a fair digitally-shot replication of 1950s colour, in period-appropriate Academy Ratio) and set in period, not entirely specified when but around the time the original film was made. The film follows the original quite closely, and reproduces its two-thirds/one-third structure, though is some forty minutes shorter. It does remove some scenes from the original, such as Watanabe’s confrontation with gangster site developers, which most likely would not work in a British context. It’s a good film, showing a Japanese-born writer tackling the rituals and hierarchies of British society as he has in other works, not least the civil service in which Williams has spent his life, though does exist as a pendant to the original. It does soften some aspects, such as having its equivalent to Toyo (Margaret, played by Aimee Lou Wood), not disappearing from the film at the protagonist’s death but turning up to his wake and, it’s implied, pairing off with one of Williams’s work colleagues. The film received Academy Award nominations for Nighy as Best Actor and Ishiguro for Best Adapted Screenplay.

Ikiru is released by the BFI on a two-disc Blu-ray edition, with the feature and commentary on Disc One and the additional extras on Disc Two. Both discs are encoded for Region B only. Ikiru carried an A certificate on its original release and is now a PG. The two short films on Disc Two are documentaries which are exempted from classification as neither contain any material which would earn anything higher than PG.

The film was shot in black and white 35mm in Academy Ratio and so this transfer, based on Toho’s 4K restoration from a finegrain duplicating positive, no doubt the earliest-generation film element available and in existence, is in the intended ratio of 1.37:1. There is some very minor print damage here and there, but generally the image is sharp and detailed, with the contrast so vital to black and white looking spot-on. Grain is natural and filmlike.

The sound is the original mono, rendered as LCPM 1.0. Although this is not announced on the disc menu, nor in the booklet, nor indeed in the press release I received, there are two versions of the soundtrack: restored and unrestored, which was the case on several of the BFI’s other releases of classic Japanese films. The default is the restored one, though you can select the unrestored version via your remote as Track 2. The restored version is a little warmer, though not without being slightly muffled, while the unrestored is a little brighter, but hiss is more noticeable if not too distracting. English subtitles are optionally available for the feature. They are also on It is Wonderful to Create on Disc Two, though the Japanese-enabled (I am not) can switch them off via the remote if they wish.

Commentary by Adrian Martin

Adrian Martin has provided many commentaries on the BFI’s releases of classic Japanese films, on those I have reviewed here by Ozu, Naruse and now Kurosawa. Often on his commentaries, he spends a lot of time talking about what other scholars and critics have said about the director and the film. There’s less of that here, or rather proportionally less due to the film’s length. He says up front that he won’t go into production details much, but does talk about the writing process which is after all particularly significant here. However, he does go into some detail about some of Kurosawa’s techniques, such as his methods in filming “iterative” sequences, ones where the idea is to convey something which happens repeatedly, without showing it multiple times. Kurosawa fan Steven Spielberg has done the same thing in many of his films, and he seemed to have learned this from Ikiru, his favourite of his works. Martin also discusses Living, though mostly to point up differences between original and remake. It’s a constantly interesting commentary with very few dead spots even in nearly two and a half hours.

Akira Kurosawa – It Is Wonderful to Create – Ikiru (41:37)

Made in 2002 by Toho, this is one of a series of featurettes about the making of Kurosawa’s films made for the company. The overall title comes from a quote by the director. This covers the film in more depth than you’d get from many similar pieces, going into some of the subtleties of Kurosawa’s techniques, such as the light reflections in Watanabe’s eyes mentioned above. We also hear about the film’s use of music, and Kurosawa’s late decision (after a cast and crew screening) to remove music from one key scene. There are interviews with several people involved, Kurosawa included including Takashi Shimura via archive footage, and he is praised for his acting drunkenness, with the suggestion that actors who never drank were the best at playing inebriated. Watanabe was his first lead role. An excellent addition, but watch it after you’ve seen the film.

Introduction by Alex Cox (14:46)

From 2003 and previously available on the BFI’s DVD of Ikiru, this mirrors the main feature in its two-thirds/one-third construction, but I doubt that’s anything other than coincidence. In the first two thirds, Cox provides an overview of Kurosawa’s life and career, from his birth in 1910. That was, as Cox points out, during the twentieth century, but Japan was rather less advanced than in the West and Kurosawa’s father was quite feudal in his attitudes. He did however like the cinema and Akira and his older brother Heigo saw a lot of films from quite a young age. Heigo had a job as a narrator for silent films but with the arrival of talkies he and others began to lose work, and in 1933 Heigo took his own life. Cox then talks about Akira’s entering the film industry, which he did in 1936 as an assistant director at the company which later became Toho. His career had some ups and downs, with an unsuccessful excursion to Hollywood with his being removed from the production of Tora! Tora! Tora! (1970), which adversely affected his career, leading to a suicide attempt in 1971. His fortunes revived with the Russian-made 70mm production Dersu Uzala (1975) and his later films Kagemusha (1980), backed by devotees George Lucas and Francis Coppola, and his take on King Lear, Ran (1985). His final film was Madadayo (1993) and he died in 1998. The final third of this piece is a specific look at Ikiru itself. Inevitably this overlaps with other items on this disc, as Cox talks about the scripting process and in particular Shimura’s role in the film.

Trailer (3:30)

A rather lengthy trailer for something you might wonder being a hard sell if it wasn’t for its director’s reputation. There are some shots in the trailer that aren’t in the film itself.

Image gallery (4:05)

A self-navigating show which begins with two poster designs in colour, followed by production stills, all in black and white.

It’s Ours Whatever They Say (38:46)

It’s a hallmark of BFI releases that they include extras that aren’t directly relevant to the film itself but tangential to its themes. But here accompanying a film from 1952 which involves a campaign for a children’s playground, we have a real-life documentary made in 1972 about a campaign for just such a playground. This one was in Islington, North London, and came about when a young boy fell to his death in a derelict timber yard. The mother of another boy who had witnessed the incident started a campaign to convert the yard into a playground as there wasn’t anywhere locally for children to play. However, the local council had plans to turn the site into housing.

It’s Ours Whatever They Say was directed by Jenny Barraclough (spelled “Barracough” in the end credits, which are as with the main title painted onto walls) and was shot in 16mm. It was shown on BBC2 in the Man Alive slot on Wednesday 5 April 1972, with a repeat showing on Saturday 8th. That programme was in a fifty-minute slot, with the film itself (which is transferred on this disc at 23.97 frames per second but would have been broadcast at 25 fps so would have shed about a minute and a half of running time) preceded by an introduction and followed by a studio discussion on the issues raised. The odd thing is that the film is on this disc in black and white when it was filmed in and broadcast in colour, even if the majority of viewers in 1972 would have had black and white TV sets. The entire programme, complete with countdown clock and the introduction and discussion, can be seen in colour at the director’s YouTube channel.

The People People (22:26)

Made by the Central Office of Information in 1970, this is a recruitment film for the civil service, a dramatised documentary in which a young photographer makes a photo essay about the work of British civil servants. This film is rather self-consciously of its time, with psychedelic-style guitar noodlings on its soundtrack, and not least Sousa’s “Liberty Bell” which at that time had already become associated with Monty Python’s Flying Circus. This was shot in the luxury of 35mm (from this transfer, now a little faded), but it doesn’t appear to have had a cinema release as the kind of supporting short you might have bypassed to stock up on popcorn, hot dogs or Kia-Ora (other fruit-based beverages were available) while waiting for the main feature to start.

Booklet

The BFI’s booklet, available with the first pressing of this release only, runs to twenty-four pages. With a spoiler warning attached, it begins with an essay by Tony Rayns, an authority on Asian cinema who isn’t otherwise represented in this release. He sees Ikiru, with its contemporary setting, as a commentary on a country then under American occupation, though censorship of the time would have forbidden any mention of it. He also points out some ironic subtleties that non-Japanese viewers might miss and aren’t conveyed by the subtitles – the old file in Watanabe’s desk is his own report on departmental efficiency, dating from before the War. Rayns talks about the structure of the film and the use of the narrator, comparing Kurosawa’s view of post-War family dynamics with that of Ozu, and the film’s overall lack of the sentimentality that Kurosawa and his great influence John Ford could be prone to.

After a cast and crew listing, the booklet reprints John Gillett’s 1959 Monthly Film Bulletin review referred to above. Then there is “Shimura Takashi: To Live a Wonderful Life” by James-Masaki Ryan. (Both Rayns and Ryan in their essays use Japanese naming order, surname first.) As the title indicates, this is a look at the actor who rather surprisingly was a favourite of none other than Steven Seagal. Ryan’s piece covers Shimura’s life and career from his birth in 1905 and his entry into the film industry with a role in a silent film in 1934. Despite the qualities of his speaking voice, he wasn’t heard on screen until his fourth film, and demonstrated his singing abilities in 1939. Most often cast in supporting roles, he became Kurosawa’s most-used actor with twenty-one films, starting with the director’s first, Sanshiro Sugata (1943). He often acted opposite Kurosawa’s other great acting collaborator, Toshirō Mifune, but displayed a greater range. Shimura lost weight for his role in Ikiru, though some of that was due to having recently had surgery for appendicitis. Ryan ends his essay on a personal note, as cancer has featured on both sides of his family, and because of that Watanabe has been an inspiration to him.

The booklet also contains notes on and credits for the extras, with longer pieces by Katy McGahan on It’s Ours Whatever They Say and Tony Dykes (a former COI employee) on The People People, ending with a poem based on his experiences there.

Seventy-two years after it was made, Ikiru remains one of Akira Kurosawa’s greatest films, and is certainly at the top of his contemporary-set films. It’s well presented on this two-disc Blu-ray from the BFI.

|