| |

"What currently insists on truth is disproved, because Lie or her younger sister, Deception, often hands over only the most acceptable part of memory, the part that sounds plausible on paper, and vaunts details to be as precise as a photograph." |

| |

Günter Grass, from Peeling the Onion, 2007 |

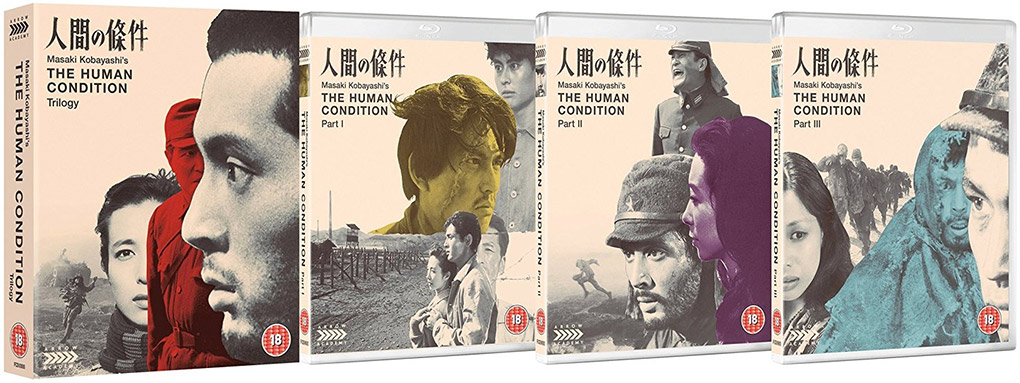

Masaki Kobayashi's The Human Condition/Ningen no Jôken (1959-1961) is one of the most soul-searing indictments of war and the authoritarian mind-set ever committed to film. With a running time of 579 minutes, Kobayashi's magnum opus pulls up just shy of the ten-hour mark but it falls short in few other respects. A cautionary tale of unravelling idealism and unflagging hope, it charts the development and degradation of a principled rebel who is opposed to violence and injustice but deeply implicated in both. It chronicles his circular odyssey from a Japanese steel-mine-cum-concentration-camp, via training barracks and the Manchurian front, to a Soviet timber-plant-cum-concentration-camp. As wide as it is deep, this story of history renders Japan's defeat in the Pacific War and its hero's loss of moral compass as a hiding for humanity. It is, among other things, a poignant love story, a plea for peace, a potent meditation on fascism, a cinematic soap opera, a neo-realist examination of Japanese fascism, a charge sheet of our common failures and frailties, an epic tragedy, a string-laden melodrama, even, at times, if unintentionally, a black comedy. A haiku it ain't.

As a raw record of a disgraceful episode in Japanese history, the brutal occupation exploitation of Manchuria, it is unparalleled. As persuasive counter-history it is exemplary. As a parable of humanity's trial by fire in the crucible of war it has few equals. As all this were not achievement enough, it is also one of the most visually stunning films ever made, graced as it is by Yoshio Miyajima's majestic cinematography - which glides, dives, slides and soars its way into cinema's hall of legend. Contributing to one of Sight & Sound's perennial round tables proposing a 'new cannon', Nicole Brenez says The Human Condition 'deserves to be considered as "the best" film in the history of cinema.' 'It could,' she adds, 'become the most necessary and revered film for the next decade.' Already, with little critical support, it proudly stands shoulder to shoulder with great narrative anti-war films such as Jean Renoir's La Grande illusion (1937), Roberto Rossellini's War Trilogy (1945-48), Stanley Kubricks's Paths of Glory (1957), Kon Ichikawa's Fires on the Plain/Nobi (1959), Francis Ford Coppolas' Apocalypse Now (1979) and Elem Klimov's Come and See/Idi I smotri (1985).

In content, style and tone, The Human Condition sits closest to Kon Ichikawa's contemporaneous, equally unforgettable and urgent firecracker. Ichikawa's film was based on Shôhei Ôoka's 1951 novel, Kobayashi's upon Junpei Gumikawa's six-volume bestseller of 1958. The source novels derive much of their force from their authors' haunting experiences as soldiers and prisoners of war. The films were similarly cathartic exercises that helped their directors and their nation come to terms with the emotional carnage of anger, despair and crippling guilt. Ichikawa and Kobayashi tend to be bracketed within the 'humanist' tendency of Japanese cinema's post-war golden age. They would combine, in the late sixties, with two others from that 'school', Keisuke Kinoshita (who taught Kobayashi his craft) and Akira Kurosawa, to form a loose collective, Yonki-no-kai ('The Club of the Four Knights'). Their aim, akin to United Artists in the U.S., was to produce films independently in response to a crisis in the Japanese film industry that saw box office takings halved and studios become increasingly risk-averse. By this time, major studios such as Daiei and Shin-Toho had collapsed and others were turning to pinku eiga (soft porn) or roman poruno (romantic porn). Sadly, their combined efforts ended in disaster. Despite the feelings of friendship and mutual respect that united them, they couldn't work together. Their co-operation on the unfinished jidaigeki (period) film Dora-Heita and on Kurosawa's ill-fated modern fable Clickety Clack/Dodes'ka-den (1970) ended in commercial, creative and critical failure. In a sad echo of Kobayashi's Harakiri/Seppuku (1962), Kurosawa attempted suicide soon after the debacle. The others, less deeply wounded, pressed on and would be reunited one last time, beyond the grave, when Kon Ichikawa finally finished Dora-Heita (2000).

Both The Human Condition and Fires on the Plain depict the defiant footslog, across desolate and deserted landscapes, of defeated soldiers clinging tenaciously to life and the last shreds of human dignity against all odds. In both, the officer class fights senselessly and suicidally to the death. Both films deploy monochrome widescreen photography to dazzling effect. Both turn a long, clear-eyed stare upon the horrific aftermath of the Pacific War and examine its lingering implications for humanity. Godard has argued that, with Rossellini's Rome Open City/Rome citta aperata (1945), 'Italy regained the right of a nation to look itself in the face.' Much the same could be said about these towering achievements of Japanese cinema in relation to Japan's rapprochement with its recent past. We should add, though, that such redemptive films afford humankind the right to look itself in the face again. Ichikawa said he'd tried to confront 'the pain of the age'. He also remarked that while he remained sanguine about humanity and retained high hopes of finding evidence of 'humanism' in Japanese society, he had failed to find it there.

While the tonal similarities and political affinities connecting The Human Condition and Fires of the Plain are striking, Kobayashi's film is longer, more discursive, and, occasionally to its detriment, more flamboyant. Released as three consecutive two-part films, it adheres as closely to the plot details as to the structure of Gumikawa's novel. Each part of the trilogy, however, has its own distinct cinematic style. As the film's protagonist, Kaji (Tatsuya Nakadai), descends into madness, Kobayashi gradually abandons the deep-focus realism with which he begins and veers off toward melodrama. By its final third, A Soldier's Prayer, the film resembles a Douglas Sirk picture – one without the vivid colour and set in a concentration camp granted, but with all the strings and heartbreak of a Hollywood weepie nevertheless. By the time Kobayashi completed The Human Condition, Gumikawa's novel had sold two and half million copies. The film was a huge box office success and owed much of its popularity to a general desire to see the book 'made flesh'. We may find it hard to picture queues around the block for a film this dark, intense and confrontational, but if Japan often seems like a different world to us now, back then it would have seemed a different world even to itself. To be more precise, their world, as they had known it, had collapsed. We'll consider the reasons for the film's popularity below but begin by asking a couple of pertinent questions about how history is received and retrieved.

Emerging as it does from the gap between realism and melodrama, then and now, reality and its representation, The Human Condition forces us to ask what we really know about the past. Well, we know that Joe Rosenthal's photograph of six marines raising the stars and stripes on Iwo Jima, in 1945, is not all it appears to be. We know the one Yevgeny Khaldie took, a few weeks later, of a Soviet soldier waving the hammer and sickle above the Reichstag isn't either. We know that a certain Police Chief executed a Viet Cong soldier without trial on a Saigon street, in 1968, because Eddie Adams and his Leica caught him in the act. And we know what happened to young Phan Thi Khim Puc a couple of months later, because Huynh Cong Ut took a photograph of her as she fled, naked, after a U.S. napalm attack. Her words are also on the record: 'Too hot, too hot', she screamed. Those willing to face unpleasant facts can watch archive footage of the revolting events recorded by Adams and Ut.* Each of those photographs, like the moving images Kobayashi bequeathed us, tells a powerful story. Each has been fiercely contested. Irrefutable images of traumatic atrocities coexist with doctored 'evidence'. In recent weeks, a debate has raged over Facebook's decisions, first to erase Ut's iconic image from their pages and then, by public demand, to reinstate it. On this occasion, the 'right to know' and the individual image's fame trumped squeamish modern mores and corporate ignorance. Our ways of seeing and relationship to the past are constantly changing, though, and such changes demand attention.

The Human Condition, a film as fearlessly ambitious as its title suggests, attempts no less than the redemption of a defeated nation and the rehabilitation of humanity. Kobayashi wrote and rewrote Japanese history using the narrative arts. Could he have achieved his ends by documentary means, and would we have believed him today if he'd decided to do so? Susan Sontag, reflecting on the paradox that symbolic but substantial images record time as they shrivel before it, said they offer 'an interpretation of what is real, but at the same time a spoor – like a footprint or a death mask.' The Human Condition offers such a spoor – a material trace of the past, an impression of history.

Already dented by countless revelations of documentary dishonesty, the public's fragile faith in 'transparent truths' has been further eroded, of late, by Photoshop, 'analogue obsolescence' and digitisation. Already damaged by deliberate official distortions, our sense of history has been further complicated by information overload and image glut. 'He who reads much and travels much, sees much and understands much,' said Cervantes (El que lee mucho y anda mucho, ve mucho y sabe mucho). He who downloads much and seldom leaves his computer may see little and understand less. You may share my discomfort upon discovering that Transport for London frequently employs the appalling acronym S.S. when referring to its station supervisors in internal memos. You can imagine my shock and surprise when I subsequently discovered that the twenty-eight year adult I immediately shared my discomfort with had never heard of the Schutzstaffel. Not the word, you understand, the organisation and its indescribable history. What might that bright and articulate, if ignorant individual not know about the Japanese history? What might she take for truth and what discount as irrelevant? How would she react to The Human Condition, if she were ever to watch it? Fat on peace, what do any of us really react to? A unwelcome line from Nick Cave's 'More News from Nowhere' springs to mind: 'Someone must've stuck something in my drink coz everything's getting strange, half the people are turning into squealing pigs and the other half are cooking.'

In today's (post-medium, post-cinema, post-literate) image-saturated world, in these times of amnesia and relentless homogenization, we expect an element of subjectivity and manipulation in even the most ascetic, seemingly straightforward representations of reality. Despite our healthy scepticism about images as 'evidence' and our democratic resistance to polluted accounts of the past, the perception persists that pro-filmic documentary images have greater 'truth claims' than those principally produced to entertain. The Human Condition is neither documentary, in the strictest sense, nor entertaining, in the narrow definition of the term, but it is indubitably imbued with its own (debatable) 'truth claims'. Our ambiguous, often muddled relationship to mediated images of the past is defined by suspicion about the instability of images as 'pure' indexical signs and by feelings of temporal disparity (that was then, this is now), but it is increasingly shaped by awareness that a hierarchy of intentions lies behind their production. For this reason, more attention than ever is now paid to the ways the past is created by images, to the ways we experience the past through them, and to the motives of those who manufacture meaning from them. This seems worth considering in discussion of films that treat history and themselves become part of history; doubly so in the case of The Human Condition given that it emanates from a centred culture that refuses the separation of past and present and strives to remain true to the hopes bequeathed to the living by the dead.

In the field of visual studies, the idea that 'seeing is believing' is now taken with a spoonful of salt. In history departments, the notion that 'the facts speak for themselves' is now regarded as equally naïve. The crisis in confidence surrounding photographic indexation has been accompanied by a parallel crisis in historiography or 'the history of history'. E. H. Carr's seminal work of 1961, What is History?, helped establish the centrality of subjectivity and interpretation to the writing of history. A year later, E. P. Thompson's The Making of the English Working Class sought to rescue the common citizenry from 'the enormous condescension of posterity' (and, it must be said, of E.H. Carr). Hayden White's 1973 book Metahistory pushed the argument further by insisting that history is told as a story with a beginning, middle and end. Since then a range of radical counter-histories have taken up the challenge of writing corrective 'history from below'. Black, feminist, gay, anti-colonial and anti-imperialist historians have continued to contest official accounts (notably as distorted by Heritage Cinema) and to place history's 'losers' centre stage where they belong. As John Lewis Gaddis notes in his monogram The Landscape of History, these counter-hegemonic histories have generally been at odds with 'the form of deconstruction practiced by some postmodernists, who confuse the indisputable fact that social constructions do exist with the highly disputable proposition that their own findings are not among them.' In short, portrayals of the past are subject to constant amendment, challenge and revision and it is now widely accepted that History and the history of images alike are concerned with representations of reality, which is to say, that all histories and all images have ideologies attached to them. Ewan McColl once freely admitted he made propaganda – for peace and social justice.

Given the currents and processes hinted at above, it seems sensible to ask what motivated Kobayashi to make The Human Condition as he did, when he did, and to consider this magnificent film in the context of seismic changes in post-war Japanese society. An essay by Naoka Shimazu in the booklet accompanying Arrow's Blu-ray release of the film helpfully provides an overview of debates about Japan's relationship to the Pacific War. She delineates the process of 'redesigning the past' by which Japan reached an uneasy accommodation with its wartime record – essentially by accepting 'the half-baked myth that all Japanese were victims of pre-war and wartime militarists'. This myth enabled the Japanese to 're-invent themselves as pacifists' and 'keepers of the memory of the atomic bombs'. As Bob Wakabayashi says forthrightly in his review of James Orr's book The Victim as Hero: 'Their post-1945 myth, that of being war victims extraordinaire, formed the basis of a reconstituted national myth, that of being pacifists extraordinaire . . . the Japanese have atoned for past war crimes by staunchly refusing to commit any new ones, whereas the same cannot be said of the Americans or even the Chinese and Koreans since 1945.' In short, Article 9 is now as sacrosanct as the Hinomara and the imperial rising sun sits in the dustbin of history where it belongs.

Naoka Shimazu concludes her excellent essay by noting that these new notions of national identity 'rest uneasily on the bed of political conservatism, therefore, the constructed identity of the post-war Japanese is inherently unbalanced'. The schizophrenic imbalance she refers to is not, of course, confined to Japan. We concluded our review of Anand Patwardhan's indispensible dissection of Indian nuclear militarism, War and Peace/Jan aur Aman (2002), by quoting Kazumi Matsui, the Mayor of Hiroshima. On the occasion of the 70th anniversary of the infamous American attack on his city, he said: 'Our world still bristles with more than 15,000 nuclear weapons, and policymakers in the nuclear-armed states remain trapped in provincial thinking, repeating by word and deed their nuclear intimidation . . . To coexist we must abolish the absolute evil and ultimate inhumanity that are nuclear weapons. Now is the time to start taking action.' That figurative call to (lay down) arms chimes with Kobayashi's pacifist convictions and career as one of Japan's most lucid, outspoken critics of its orthodoxies.

Kobayashi's four-and-half-hours long compilation film Tokyo Trial/Tôkyô saiban (1983) documents the post-war International Military Tribunal for the Far East during which 28 Class A war criminals were found guilty and several, including Prime Minister Hideki Tojo, were sentenced to death by hanging. Less well known than the trial at Nuremberg, this tribunal also raised more questions than it answered. Independently produced by Kôdansha and assembled from over 170 hours of archive footage (partly provided by the Pentagon), it combines a forensic re-examination of that trial with a short history of Japanese imperialism in the first half of the 20th century. As Linda Hoaglund suggests in the booklet in the box set, Kobayashi's documentary can justifiably claim to be 'the definitive record of Imperial Japan.' It opens with images of the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, takes in the nuclear tests at Bikini Atoll and the rape of Nanking, and ends by lingering on Huynh Cong Ut's aforementioned image, 'Vietnam Napalm'.

One would assume Kobayashi's polemical intentions were plain but in its review of the film the New York Times declared: 'Obviously his sympathies are with the defendants and with his country.' That claim is as far from the truth as Hiroshima is from Manhattan. Far from being an apologist for the Japanese military and the revisionist right, Kobayashi actually spent his entire life contesting the official version of history from the left and challenging the entangled myths surrounding neo-Confusian Tokugawa ethics, the toxic Bushido code, Japan's imperial past, and her role in the Second World War. This was not a man inclined to sympathise with Japan's authoritarian establishment. Here, in fact, was a man who had seen more than most and would not take it anymore, as a glance at his biography should suggest.

Born in the port city of Otaru on Hokkaido, Kobayashi grew up in a non-conformist family that respected and encouraged independence of mind. Having learned to question received wisdom from an early age, he was drawn to philosophy, which he studied alongside Oriental art at Waseda University in Tokyo. He would return to Hokkaido and to the philosophical concerns of his youth when he came to direct The Human Condition. After graduating in 1941, Kobayashi joined Shôchiku studios but war soon cut short his filmmaking apprenticeship and he was sent to the front in Japanese-occupied Manchuria. An able soldier and crack marksman, he repeatedly refused promotion and his (partly consequential) experiences of brutality in the army and later as a POW on American-occupied Okinawa, cemented his radical politics and pacifist worldview. Released in 1946, he returned to Shôchiku where he worked under the tutelage of Keisuke Kinoshita, directing a couple of light melodramas before cutting loose with his first major film, The Thick-Walled Room/Kabe atsuki heya (1953).

Based on the published testimonies of 'war criminals', The Thick-Walled Room is an indictment of the unjust system wherein the burden of blame fell on Japan's common foot soldiers rather than her far more culpable top brass. The question of compensation for victims of imperial arrogance and aggression was a hot topic at the time. Demobbed service personnel and their dependants, atomic-bomb victims, landlords whose property was sequestered during the U.S. occupation (officially, 1945-1952), the widows of dead soldiers – all received ample restitution. But what, asks James Orr in The Victim as Hero, of the 'comfort women' forced into sexual slavery or the Koreans and Chinese forced into slave labour – whose brutal treatment is highlighted in the first third of The Human Condition? What of Allied POWs – such as those who appear in David Lean's The Bridge on the River Kwai (1957)? Why were high-ranking war crimes suspects granted generous pensions while the suffering people and maimed soldiery received next to nothing?

The Thick-Walled Room was supressed for three years by studio bosses afraid of offending the Americans, so Kobayashi was forced back into studio hackwork again. It was not long, though, before he burst his shackles with two further kieko-eiga or 'social problem' films: I'll Buy You/Anata kamasu (1956), an allegorical tale of corruption in Japanese baseball; and Black River/Kuroi kawa (1957), an exposé of the black market, prostitution and gambling rackets that grew up around the U.S. military bases. Although this subject matter implicates the Americans, Kobayashi's anger was primarily turned inwards, at the enemy within: his conformist, compliant and complicit compatriots. In his next project, The Human Condition, Kobayashi's hero, Kaji, says: 'It's not my fault that I'm Japanese, yet it's my worst crime that I am.'

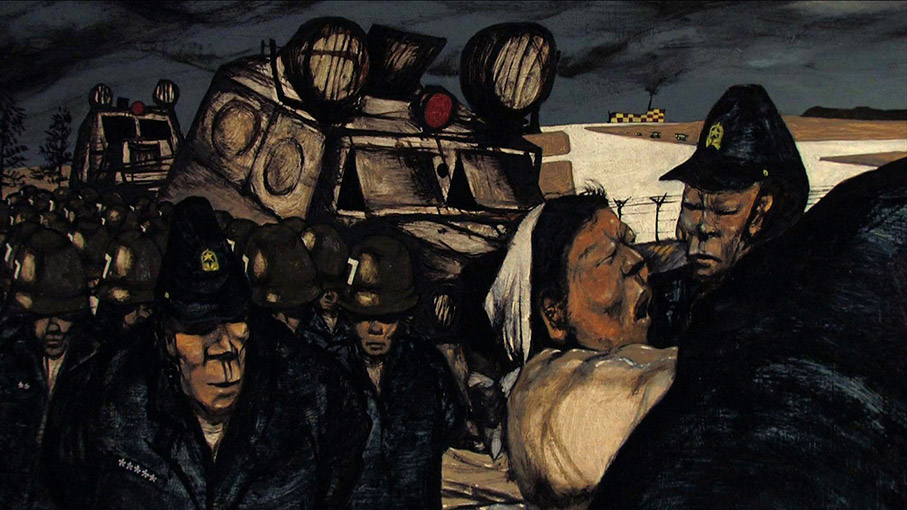

The Human Condition while never letting ordinary Japanese off the hook, lifts the imperialist rock from under which unspeakable cruelty and barbarism slithered. It roundly condemns a political system that, as Philip Kemp notes, is 'putrid from top to bottom', that debases good people while bringing out the worst in the bad. Both a product and critique of the left-leaning school of 'sentimental humanism' that flourished in Japanese literature and cinema of the late 1950s, it echoes contemporary cultural and political debates at a time of growing opposition to ANPO – the vigorously contested, widely detested US-Japan Security Treaty. By the time Kobayashi began work on The Human Condition, the vast majority of Japanese favoured non-alignment, opposed the military alliance with the U.S., and supported the idea of 'peace in one country.'

The Japanese left, having largely recovered from the demoralising climb-down over the 1947 General Strike and the decimating Red Purges of 1950, was galvanised, reunited and re-energised by the rightward lurch of the newly founded Liberal Democrats and vigorously opposed incoming Prime Minister Nobusuke Kishi's plans for re-militarization. It is scarcely surprising that he and the LDP should have designs to turn Japan into a client state of the United States. Although Kishi was a war criminal who had organised the forced conscription of Korean and Chinese workers, although he had spent three years in Sugamo prison 'under investigation' by the Americans, and although he was implicated in the bombing of Pearl Harbour, he and his party received untold millions from the CIA's notorious M-fund. Set up by General McArthur after the war with expropriated Japanese assets, the M-fund is now estimated to be worth upwards of 550 billion dollars. It corrupts and destabilises Japanese politics to this day.

| The Film Societies Movement |

|

Cultural and political life in Japan were intertwined during the 1950s. While the CIA channelled funds toward the Yakuza and funded cultural 'exchange' visits' for patsy artists, the film societies movement formed a powerful democratic counterbalance. Built on the rock solid foundations of labour movement support and often run by trade union activists, they provided an alternative distribution network and eager audiences for independent films at a time television, while increasingly popular, had yet to dent the vast and loyal audiences for cinema. The years 1957-1960 were boom time peak years for Japanese cinema, with admissions averaging around 20 million per week or over a billion per year). Prices were kept low, averaging around 60 yen as against today's average of 1,300 yen, and film society membership rose spectacularly.** In Amagasaki alone, a city with a population of just 300,000, the local film society had over 20,000 members.

Despite differences in scale, the film societies movement can be likened to the New Left Book Club in the UK in that it provided a vital forum for debate and organising base. The proactive and enthusiastic support of the film societies generated word-of-mouth 'buzz' for The Human Condition and helps explain the film's popularity. Much of the film's dialogue reflects debates between the Old and New Left; that is, loosely, between the increasingly conservative pro-Moscow Japanese Communist Party which had renounced armed struggle and now proposed a 'popular front' parliamentary politics, and the more radical, anti-Stalinist Zengakuren movement, which wasn't afraid of direct action – non-violent or otherwise as circumstances dictated or demanded. These debates are writ large in Nagisa Oshima's New Wave gem Night and Fog in Japan/Nihon no Yoru o Kir (1960). They would cause problems for the film societies. In 1962, for example, the Osaka film society was riven by conflicts over the attempts of CP activists to impose Soviet films on them. The Human Condition, though, was welcomed with open arms, not least for its positive treatment of Chinese workers. It struck a chord with audiences involved in the various long-standing political struggles that coalesced in this period – struggles that culminated in the spectacular confrontations of 'the days of rage and grief' of June 1960, the death of a young activist, Kanba Michiko, and the assassination (on live TV) of another man of principle and integrity, Socialist Party veteran Inejiro Asanuma. The film's downbeat ending reflects these defeats and deaths in 'peace' as much as those Japan suffered and inflicted in time of war.

| The Milk of Human Kindness |

|

It is often said that Kobayashi pursued a humanist (hyûmanisto) agenda. More precisely, he came not to praise liberal humanism (hyûmanizumu) but to bury it in the quicksand of its own contradictions, beneath the honest argument that power structures delimit individual agency and therefore systems must be challenged. The film's protagonist, Kaji, a middle-class socialist with strong pacifist principles, is imprisoned and compromised from the moment he accepts a job supervising slave labour in a Manchurian mine. He's cut a sordid deal with the man and is soiled. Although Kahu has presented his employers with a blueprint for progressive change, he agrees to service the military-industrial machine not, primarily, out of principled desire to improve the lot of the subaltern Chinese workforce, but in order to avoid the draft. His riven hypocrisy and circumscribed decency, then, are revealed from the outset. We are left to guess at the detail of Kaji's productivity plans but he essentially argues, after the peasant heroine of Medvedkin's The Miracle Worker/Chudesnista (1936), that cows will give better milk if they're treated with human kindness. The first third of the film, No Greater Love, depict Kaji's ill-fated attempts to reform the mine's labour relations, win the trust of the conscripted Chinese, and establish humane working conditions within an inhumane system. 'What is a man?' ask his manager, 'He's a mass of lust and greed that absorbs and excretes.' Kaji begs to differ.

Although most of his colleagues and the Kempeitai (the military police) hinder him at ever turn, he is befriended and abetted by a veteran foreman, Okishima (Sô Yamamura), who sympathises with his aims. This is one of several friendships Kaji forms with like-minded compatriots or comrades – relationships reflecting the political solidarities that were deepening as the film was made and as the left's opposition to ANPO intensified. Initially suspicious of the college boy sent to supervise his charges, Okishima is won over by Kaji's commitment, sincerity and self-sacrifice but is experienced enough to see that he is on a (literal) hiding to nothing. After a group of Chinese prisoners escape, he drunkenly staggers into Kaji's quarters to deliver a keynote speech in which he asks Kaji how long he intends to keep up his futile attempts 'to straddle a fundamental contradiction and try to justify it?' Okishima is subsequently ordered back to head office and as the two men affectionately part company for the final time, he says to Kaji: 'I'm boarding this run-down truck but you're trying to catch the train of humanity before it's too late . . . You seem prepared to pay the fare, no matter how high it is.' The film forcibly reminds us that the road (or railway) to hell is paved (or laid) with good intentions and shows how Kaji, despite his good will, forces others to pay the price of his principles. His ideals are given no space to breath, as Kobayashi drives home the point that a corrupt system corrupts all.

| The Seeds Beneath the Snow |

|

The film begins, as it ends, in the (structuring device of) winter and snow. Kaji and his lover, Michiko (Michiyo Aratama), argue beneath the crumbling 'Southern Gate of Peace' as columns of troops march past, in front of a shop window in which a replica of Rodin's 'The Kiss' is prominently displayed. Kaji refuses her entreaties even when she offers herself to him. She reacts by accusing of weakness and cowardice. Progressive for its time, this open allusion to sexual pleasure is double-edged here. On the one hand, it defies the repressive pre-war and wartime code that stifled sexuality, subjugated it to the utilitarian, procreative demands of the nation state, and enforced a delimiting division between the 'family-state' (kazoku kokka) and romantic love (ren'ai). On the other hand, it intimates that there are additional elements to Kaji's hypocrisy. Michiko eventually joins Kaji at the mine and, while there is no mention of pre-marital formalities (miai) or of the couple's respective families, we wonder whether he acts in her best interests or his own by dragging her to hell and back with him. We also wonder where his complicity in the decision to use 30 Chinese 'comfort women' to keep the workforce pliant leaves his principles. His compliance leads one admirably rebellious and resilient Chinese prisoner to accuse him of possessing 'the face of a man but the heart of a beast.'

Kaji's moral centre cannot hold and, after he finally snaps to prevent the unjust execution of several Chinese workers, he is summarily dismissed from his position, immediately drafted into the Kwantung Army of the Empire of Japan, and sent from Loh Hu Liong to the front. The second part of the film, The Road to Eternity, sees Kaji challenging authority and his compatriots once again, this time in a boot camp for raw recruits. As Catherine Russell notes in her Cineaste review of the film, the movement of the Chinese workers in No Greater Love is heavily choreographed and synchronized. They are filmed in distancing long takes, in lines and geometric blocks, to the point it recalls Susan Sontag's descriptions of fascist aesthetics as well as the crude stylisations of Soviet cinema. These set-piece scenes aside, Kobayashi generally keeps faith, at this point, with the neo-realism with which he began. The cast received extensive training in the processes of military training and the fine details of army life are replicated to the nth degree of authenticity.

Despite the stylistic differences that define the separate parts of the trilogy, there is a damaging tonal consistency. There are flashes of human empathy, in the friendships that flare up under impossible circumstances; episodes of elegant eroticism, such as the moment a ragged refugee washes herself in a stream and her beauty is revealed; even occasional interludes of lyrical tenderness, notably when Michiko, having covered hundreds of miles across war-torn terrain, is granted permission to spend one night with Kaji. The film's mood is, however, unrelentingly bleak. Kaji's closest friends tend to meet sticky (even, in one instance, literally shitty) ends, the refugee girl is subsequently raped by a couple of Kaji's cohorts; after Michiko's visit, and Kaji receives a savage beating from those who softened sufficiently to grant love its due. This flattening tonal weakness, however, flows from a concomitant thematic consistency that underpins the film's power and Kobayashi's core case that training camps and labour camps replicate the crushing conformity of wider socio-political systems.

In the training barracks Kaji confronts monolithic institutional forces and squares up to violent bullies, as he did in the mines and as he will again as a prisoner of the Soviets. He has little support from Kageyama (Keiji Sada), an old mucker from his undergraduate days who now reappears as a senior officer, but he has the moral support, at least, of his friend Shinto (Kei Sato). He, like Kaji, is under surveillance for his socialist sympathies and derided as a 'filthy Red'. When Shinto decides to desert for the promised land (sheesh, but this was 1961), Kaji's doubts surface and he cannot join him; could not, regardless, leave Michiko - now firmly fixed in his mind as a symbol of pure goodness in a world gone mad, turned bad, and, for him, about to get even worse.

Having dodged a bullet by deciding to swerve the Soviet Union, Kaji is soon to hear bullets whistle past his ear. Like Kobayashi himself, he proves himself adept as a marksman and soldier. Unlike Kobayashi (for whom Shinto stands in, in this respect), Kaji accepts promotion; here, genuinely, in exchange for the right to treat his charges with decency and spare them the inhuman cruelty of brutalised veterans. Kaji soon earns the respect of his men – partly because of his regular eruptions of conscience (notably when he defends a persecuted recruit who ultimately commits suicide), partly due to his physical courage, but mainly owing to his obvious intelligence and humanity. He takes beatings on their behalf and trains them well for the slaughter to come. As the second part of the trilogy ends, set piece warfare finally makes a brief, twenty-minute appearance. Trained to fight but poorly equipped and otherwise poorly led, Kaji and his platoon face the Soviet invasion of August 1945 without hope of success. The Red Army tanks and katyushas crush them instantly. Their commanding officer commits seppuku or harakiri. They are forced to retreat and scatter. On the run, they evade capture only after Kaji guts a Soviet sentry with his bayonet. When Tereda (Yusuke Kwazu) – a once belligerently patriotic Major's son who Kaji converts to socialism, questions him about the incident, he snaps: 'I'm a monster, but I'm still alive.'

In the final third of the film, A Soldier's Prayer, all Kaji's energy is devoted to his primordial, single-minded struggle for survival. His ideals in tatters, his illusions shattered, he clings to life and his last remaining hope – that of seeing his beloved Michiko once again. Mirroring Kaji's tenuous grip on reality and life, the film now features regular flashbacks and freeze-frames. It cuts lose its moorings in realism and sets sail for melodrama, expressionism and magical realism. Kaji and his ragged band of defeated soldiers embark on a doomed long march 'to our former lives'. The wanderings begin. They offer protection to a group of Japanese refugees they encounter in dense woodland. Among their party are two prostitutes portrayed as sympathetic characters. As was the case with a couple of the 'comfort women' we meet in the mines in No Greater Love, Kobayashi's generosity toward and compassion for them recalls the Max Ophüls of La Ronde (1950), Le Plaisir (1952) and Lola Montès (1955). These echoes return when the depleted group (an odious merchant who has already despatched his starving family simply disappears) reach what initially appears to be an abandoned farmstead but turns out to be occupied by an 'unprotected' group of women. This scene reads like one Conrad's Nostromo, as if it were set in a deserted Latin American village after the death squads have breezed by.

Their leader (played with scene-stealing poise by the incomparable Hideko Takamine), like her companions, has frequently resorted to sleeping with Red Army troops as a survival strategy. She offers herself to Kaji while his group and hers enjoy a physical conversation in a barn. He shuns her, ever faithful to his idea of Michiko and his moral code. Kaji, fair play to him, is a full-on puritan (and all hail John Lilburne) who has his basest instincts firmly in check but we know that, while many behave in with similar dignity and fidelity in wartime, the worst do not and did not. Rape and prostitution are recurring themes in the film. As the woman says: 'Nothing is more pitiful than the women of a defeated nation.' The woman she plays so convincingly here has been forced to sell herself for beans or potatoes. She is as deeply compromised as Kaji and most of us are, and therefore speaks to our times as well as those. She certainly speaks for Kaji and millions in the defeated nations, when she says: 'There's no hope of going home is there, or of my meeting my husband again? We don't even know how long we can stay alive. Our lives have been wrecked. All that concerns us is eating and keeping our strength up.'

Kaji's next act of moral courage is to surrender to a group of Soviet soldiers to spare the embattled community of women further violence. The woman whose entreaties he refused pleads for an end to violence. Kaji lowers his rifle and raises his arms in surrender. Any final illusions he might have harboured about the Soviet Union are quickly dispelled by their treatment of their forced labour. After his surrender, he is caught in a column of Japanese prisoners who are riddled with dysentery and dropping like flies. He calls a halt and tells a bemused but decent Soviet guard, 'the fact that socialism is better than fascism is not enough to keep us alive.' In another, more painfully poignant scene of misunderstanding, he attempts to reason with a panel of adjudicating Red Army officers arraigned beneath a vast portrait of Stalin. He cannot make himself understood, is misinterpreted, and contemptuously accused of being a 'fascist samuri'. 'Germans are the worst', the Soviet commander shouts at him, 'and next comes fascist Japs like you.' Realising they may starve to death, Kaji tells his friend Tereda to scavenge food. He is caught and beaten by Kirihara (Nobuo Kaneko), one of the men who raped the refugee girl to whom Kaji offered safe passage. Desperately ill, Tereda is beaten once more after disregarding Kaji's advice and being caught scavenging again. He dies, still stubbornly clinging to life, while carrying buckets of excrement back and forth from an open latrine. Incensed, Kaji vows to escape. Before doing so, he beats Kirihara to death with chains. Kaji's journey to damnation is complete. The circle is closed. All hope foreclosed, he has effectively, ironically and symbolically become a Chinese worker in a Japanese labour camp.

While far from pro-Soviet, The Human Condition isn't avowedly anti-Soviet either; perhaps hedging its bets as the Sino-Soviet split gathered momentum. Boris Pasternak's Dr. Zhivago may not have escaped the Soviet censors but de-Stalinization and the Khrushchev Thaw saw a partial parting of the Iron Curtain as Kobayashi was hard at work. Well over half a million Soviet citizens travelled overseas in 1957 and the World Festival of Youth that year welcomed 30,000 foreign visitors to Moscow. Khrushchev urged Komsomol activists to 'smother foreign guests in our embrace'. In Morgan: a Suitable Case for Treatment (1966), Morgan and his mother visit Marx's grave in Highgate cemetery and she says: 'Your Dad used to love coming here. You know he wanted to shoot the Royal family, abolish marriage, and put everybody'd who'd been to public school in a chain gang. Yes, he was an idealist your Dad was.' Kaji is an idealist too and as naïve as the rest of us. He believes, or wants to believe, in the Soviet Union as 'a better world beyond that border . . . where they treat people like human beings.'

It's easy to snort at such idiocy, easy to read history with the benefit of hindsight, but hard not to laugh – mischievously, deep inside, and with a sense of sadness – at Irene Handel's one-liner in Morgan. A fundamentally flawed, oppressive and murderous but nevertheless symbolically vital form and focus of resistance died, in 1992, when the democratic forces unleashed by perestroika and glasnost erupted. As Chris Marker says in one of his letters to Alexsandr Medvekin in The Last Bolshevik/Le Tomeau d'Alexandre (1992): ' . . . and that would be the end of utopia. Not yours, but the very idea of utopia. As if the Soviet Union had been the amnesic bearer of a hope it had long since ceased to incarnate but which, strangely, would die with it.' Reviewing Marker's film, Jonathan Rosenbaum says it asks what it meant to be communist – and what it means to think about communism today. Most people wouldn't care to think about what it meant to be a 'Tankie' or a Stalinist. Surely, though, something precious has been lost and something dangerous is afoot if we no longer dare even to think about communism and the utopian promise it repressed but once, if only until Krondstadt in 1921, contained.

Hideko Takamine's appearance in The Human Condition points to an additional explanation for the film's puzzling popularity. It was often shown at all-night screenings and she, and others from the cast, helped promote it with personal appearances. With her soft, vulnerable beauty and extraordinary talent, she was Japan's 'golden girl', an internationally renowned actress who had already worked with Kurosawa, Naruse, Kinoshita and Ozu. Her husband, Zenzô Matsuyama, to whom she was introduced by Kinoshita, co-scripted the film. Tatsuya Nakadai, too, was already an established star who had already worked for Ichicawa, Kurosawa and Kobayashi (on Black River). In the Japanese context, this would have been a 'star-studded' film with a 'stellar cast' on the level, almost, of Hollywood spectaculars such as, say, The Longest Day (1962). Watching Takamine and Nakadai, re-living a living hell through and with them, they would have felt their pain and their own. A problem shared is a problem halved and, as we've said, to add to the film's popular appeal, there's the love story of Taji and Michiko, like something out of David Lean's Dr. Zhivago (1965).

Why The Human Condition broke post-war attendance records when it was released in Germany (as Barfuß durch die Hölle) is another matter. The trilogy's episodic format, length, and gigantic ambition calls forth comparison with Fassbinder's Berlin Alexanderplatz, a 15-hour long, 14-part adaptation of Alfred Döblin's mighty novel, and Edgar Reitz's 15-hour long, 30-episode film series Heimat (1984-2013). Kobayashi's film is longer than it needs to be, but it has a similar appeal, namely that of an unnaturally intelligent and beautifully shot soap opera: the experience of total immersion, the familiar locations, the familiar actors, and the identification with known characters. Although best experienced in a single sitting, ideally in a cinema, The Human Condition can equally well be appreciated and digested in bite-size slithers, like any novel and like those films by Fassbinder and Reisz. It should be noted, though, that while Fassbinder and Reitz in Germany, and Kon Ichikawa and Nagisa Oshima in Japan developed a close relationship with television, Kobayashi detested the medium and avoided it as much as possible. Despite his contempt for the form, it clearly influenced the structure and style of his film, if only by a process of osmosis.

| Vergangenheitsbewältigung |

|

The deeper parallels between post-war Germany and Japan are obvious. If Döblin's Franz Biberkopf was a Good Soldier Švejk or Woyzeck for Weimar Germany, Kaji is emblematic of the tortured soul of defeated Japan. Döblin says of Biberkopf; 'he is at war with an external force, unpredictable, something that looks very much like fate.' For Kaji, life and fate are wedded to that of a militaristic machine that affronts and derails his decency, clashes with his anti-authoritarian attitudes, and renders his politics untenable. Perhaps Kaji more closely resembles Oskar Matzerath (the innocent refusenik immortalised by Günter Grass and, later, Volker Schlöndorff in The Tin Drum) than Döblin's proletarian anti-hero, but it's easy to see why Japanese and German audiences identified with him and with Kobayashi's honest account of the war.

Whatever its failings as a work of historical scholarship, Daniel Goldhagen's Hitler's Willing Executioners laid to rest the 'No Hitler, no Holocaust' line that still had purchase when The Human Condition appeared in German cinemas. The three million Soviet POWs and several million Jews who died in Nazi concentration camps weighed like lead on Germany's re-awakening conscience and the Vergangenheitsbewältigung (coming to terms) movement had only just been forced into motion by the publication of Günter Grass's explosive 1959 novel The Tin Drum. Is it mere accident that the original dust jacket adorning Grass's masterpiece looked so Japanese? The appearance of Kobayashi's film helped push that process forward in Germany as it pushed forward a parallel process in Japan. It might even be argued that it performed the same function, in Japan and Germany, that Alain Resnais's Night and Fog/Nuit ou Broillard (1956) or Edgar Morin & Jean Rouche's Chronicle of a Summer /Chronique d'une été (1961) performed in France. Those films turned a spotlight on Vichy's deportation policy, intensified the growing resistance to the myths of 'resistencialism', and hastened France's rapprochement with her collaborationist past. Like The Human Condition, they foreground the density of cinema's relationship to history and to its own history. It alerts us to the ways cinema 'subjectifies objectivity and objectives subjectivity' – to borrow a cumbersome but precise phrase coined by Dominic Chateau in relation to Edgar Morin. To push this line of reasoning a step further, and backwards, perhaps The Human Condition has something in common, too, with Robert Weine's Das Cabinet des Dr. Caligari(1920), a film scripted by two pacifists which, Seifried Kracauer suggests, predicted the rise of the Nazis. Kracauer may have exaggerated the extent to which Expressionist cinema in general, and Dr. Caligari in particular, reflected the collective psychology of the German people, but he didn't exaggerate the extent of the deep and darkening crises in German society. The Human Condition owes a distant debt to that film, as most films do, and, in its final third, it often becomes markedly expressionistic, as does Tatsuya Nakadai acting.

Lotte Eisner may herself have been prone to exaggeration, and she certainly exacerbated anti-German sentiment both in her generalisations about the German national character and suggestions about German exceptionalism, but she captured something of the atmosphere of Weimar Germany when she wrote: 'Mysticism and magic, the dark forces to which Germans have always been more than willing to commit themselves, had flourished in the face of death on the battlefields. The hecatombs of young men fallen in the flower of youth seemed to nourish the grim nostalgia of the survivors. And the ghosts that haunted the German Romantics revived, like the shades of Hades after draughts of blood.' Eisner's comment may shock us as much as it will appall modern Germans, but it will also strike a chord with those familiar with Goldhagen's Hitler's Willing Executioners and, I suspect, would have found favour with Masaki Kobayashi. He was, after all, confronting the 'dark forces' in Japanese society.

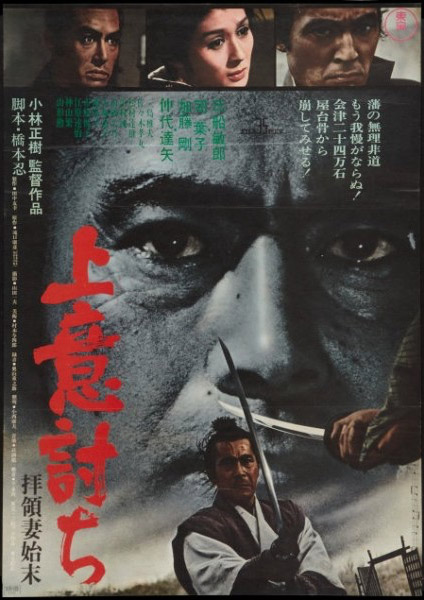

After completing The Human Condition, he would turn his attention to ancient forms of mysticism and magic in Kwaidan (1965) and, in Harakiri (1962) and Samuri Rebellion/Joi-uchi (1967), to the feudal system challenged, before him, by masterless rônin. With the continuing assistance of Tatsuya Nakadai, he continued to contest history but his jidaigeki films are as much about the present as the past, reflecting Japanese culture's insistence on the continuity between then and now. Again, he holds systems not individuals to account. In response to a question from Linda Hoaglund, he said: 'All of my pictures, from a certain point on, are concerned with resisting entrenched power . . . That's what Harakiri is about, of course, and Rebellion as well. I suppose I've always challenged authority. This has been true of my life's work, including my life in the military.' It was a life well spent and, although he refused military awards, one garlanded with honours. Hildegard Bachert described Käthe Kollwitz, that indefatigable pacifist and campaigner for social justice, as 'Germany's noble conscience in its darkest hours.' Masaki Kobayashi was Japan's noble conscience in its darkest hours. In his Story of Cinema, David Shipman called The Human Condition 'unquestionably the greatest film ever made.' Such questionable hyperbole overstates the case, but it is, unquestionably, one of the most important, courageous, moving and memorable films ever made.

Suppled for this release by Shochiku and completed on a Spirit Datacine using new prints struck from the original 35mm negatives, the 2.35:1 1080p transfers on all three discs here are in excellent shape. The contrast is punchy, with deep black levels that only really eat into the shadows and darker clothing when the lighting commands it, and the crispness of the detail far outstrips and DVD version you may have seen previously. The image has also been seriously cleaned up, with hardly a dust spot of trace of damage to be seen.

Parts one and two (parts one to four in the Japanese release version) were originally presented in mono, and the soundtracks were remastered from a 35mm optical soundtrack print. Part three (parts five and six in the Japanese release version) was the first Japanese film to be presented in stereo on its original release, and the audio was remastered from the original magnetic stems. All are in very good shape, with the expected restrictions in dynamic range balanced out by the clarity of the dialogue and the lack of background noise, hiss or any sundry damage. Chûji Kinoshita's music sounds good on parts 1 and 2, but is really full-bodied on part 3's stereo track.

Clear optional English subtitles are available and active by default. Burned in Japanese subtitles are included on the right-hand side of frame for the Cantonese dialogue.

Booklet

As beautifully designed as the box set within which it sits, the 52-page booklet accompanying Arrow's Blu-ray re-release of the film is an invaluable introduction to Kobayashi's work. It contains an extensive but not particularly revealing conversation between Kobayashi and Linda Hoaglund (recorded a couple of years before the director's death in 1996); an equally extensive and far more illuminating essay on post-war Japanese culture by academic Naoka Shimazu; and the film stills, list of credits, and notes on the transfer we've come to expect from prestigious releases such as this. The press release relating to the Arrow Academy Blu-ray release promised us a 'booklet with new writing on the film by David Desser'. It is, it has to be said, both disappointing and puzzling that that promise was not fulfilled but it feels churlish to grizzle as this booklet is pack full of invaluable material. We only hope that Dr. Desser is in rude health and will continue to inform us elsewhere.

Born in Japan to American missionary parents, Linda Hoaglund was schooled in Tokyo before completing her educated at Yale. She is a bilingual translator who has subtitled over 200 Japanese films and her knowledge of Kobayashi's work is evident both in the interview and in the introductory overview of his career that she provides. Interestingly, she has also made films on the opposition to Kamikaze pilots, the opposition to ANPO, and memories of Hiroshima. Among other things, they discusses are Kobayashi's experiences of sadism in the military, 'the lies of history', and his relationship with composer Tôru Takemitsu, whose music enhances Harakiri but who was not responsible for the occasionally heavy-handed and intrusive score for The Human Condition.

It is only to be expected that Hoaglund's hour-and-a-half long conversation with Kobayashi dwells on Harakiri as the interview was conducted as research for a documentary on Takemitsu's career. It is a shame that they barely discuss The Human Condition but even more frustrating that they didn't talk about the film she calls Youth of Japan. This reference had me baffled me until I realised that it refers to Hymn to a Tired Man/Nihon no seishun (1968). I have not, I confess, seen this film. To be frank, I'd never even heard of it before. It is described by Kobayashi as 'a post-war version of The Human Condition but, astonishingly, there's been no mention of it in any of the books on Japanese cinema I've read or own; not in Donald Richie's useful A Hundred Years of Japanese Cinema nor Noël Burch's essential To the Distant Observer, nothing either, in vital books on Japanese cinema by experts such as David Bordwell, David Desser, Kyoko Hirano, Tadao Satô, Kyoko Hirano, Joan Mellen or Isolde Standish – not even in the filmographies. Odd, most odd. I turned for guidance to our esteemed editor, who has a Japanese partner, has visited various Japanese studios, and knows more about Japanese cinema than anyone I know. He hadn't heard of the film either.

All most perplexing when one considers the claims made for The Human Condition and Kobayashi's significance. This opens up a can of worms relating copyright law, the availability of films online (where, we're often told, we can find anything), and the glacial pace of academic and critical change. It is to be hoped that Arrow, Eureka, Second Run, or some such esteemed distributor will track the film down and allow us to take a look. Watch this space.

Naoko Shimazu's Shimzu fascinating essay Popular Representations of the Past: The Case of Post-War Japan helpfully elaborates on the cultural and political contexts that help us understand The Human Condition and better appreciate it. If her emphasis is on literature rather than cinema and her tone, at times, a tad dry (as academic writing tends to be) her essay is, nonetheless, an enjoyable, instructive, and welcome addition to a release that does Arrow great credit. As one particularly perceptive online cinephile commentator has noted, it is a surprise that Eureka haven't hunted down and released this important film down before now and released it on their Masters of Cinema label; particularly so as it was previously released by Criterion, with Eureka have a strong and mutually supportive relationship.*** I suspect this has more to do with copyright issues than desire on their part but we're edging, once again, into choppy waters here so will leave it at that.

Introduction by Philip Kemp

Philip Kemp is an erudite and engaging critic so we looked forward to hearing his comments on The Human Condition. Another disappointment awaited us. His discussion of the film replicated, often verbatim, an essay previously published in the dainty booklet accompanying the Criterion release of the film. Obviously that need not concern the general public, who will find his comments informative and perceptive. Those who have already been privy to his thoughts on the film, will, however, doubtless feel a little shortchanged. At times, as Kemp speaks to camera, he glances downwards, perhaps at the aforementioned booklet. That wee quibble aside, this is a perceptive and entertaining overview of the film.

Commentaries by Philip Kemp

Kemp further enhances this superb release with six short commentaries, a pair for each of the film's three parts, shrewdly selected to illustrate Kobayashi's themes and illuminate his skills. As is the case with sotto voce commentaries of this kind, statements of the obvious coexist with astute revelations. In the first pair of commentaries (A Terrible Cargo and The Execution), he considers the arrival of forced Chinese Labour at the mine and the subsequent execution of seven of their number. In second pair (A Moment of Tenderness and The Battlefield), he focuses on the love scene at the barracks and the Soviet invasion. In the third (The Village on the Trial), on the scene stolen by Hideko Takime and the one in the Soviet labour camp played out beneath the chilling portrait of Stalin

He begins by comparing Yoshio Miyajima's exquisitely elegant shot of a train approaching the camera in No Greater Love with a similar scene in Hitchcock's Shadow of a Doubt (1943). Had Kobayashi and Miyajima seen that film, he asks. This returns us to questions of transparency and truth raised above and raises the complimentary question, does it matter whether we know or not? I say this not to suggest that the art of comparison, the bedrock of criticism, is merely a parlour game but, rather, to suggest that the history of cinema resounds with allusions and echoes, conversations and questions; some deliberate and knowing, others instinctive or inherited. Was cinema thinking out loud or talking to itself when it spread its little white lie about peasants who, unaccustomed to close-ups and editing techniques, recoiled in horror at what they perceived to be severed heads in conversation? Was Hitchcock himself deliberately referring to another of cinema's foundational myths, the tall tale of audiences fleeing the Café des Capucines in 1985, for fear of being flattened by the train the Lumière brothers filmed entering La Ciotat station? Was Godard citing Hitchcock or saluting the Lumières in the tracking shot with which he begins Contempt/Le Mépris (1966)? All we need say is that cinema has always (most markedly in its infancy) been caught between too much and little, between recognition of its own mimetic powers and awareness of the difficulty of securing the 'blind' faith of audiences; consequently, it has never been able to settle on a single defining myth and so passes myths around, from hand to hand.

Having raised such questions, Philip Kemp advisedly sets them to one side to focus on other, more urgent ones containing more urgent and important echoes. There are, as one would expect, various reminders of cinematic echoes. While discussing the hallucinatory quality of the final third of the film, for instance, he compares the village sequences with Sergio Leone Westerns and Kaji's role as leader of his ragged band to Clint Eastwood's similar position in The Outlaw Jose Wales (1976). More importantly, though, he draws our attention to the ways a sequence involving forced Chinese workers being unloaded from a train echo images of Nazi transportation trains. Discussing the empty landscapes that dominate much of the film, he points out that the Manchurian sequences were shot primarily on Kobayashi's native Hokkaido as no Japanese filmmaker could actually shoot in Communist China. While considering the battlefield sequence depicting the Soviet invasion, he notes that the Soviets barbarically invaded Manchuria on 8 August 1945; just two days after the U.S. had bombed Hiroshima, the day after the bombing of Nagasaki. This is an important observation, not only in terms of what it tells us about Stalin but also because it helps us picture the atmosphere of disorientation, fear and panic that gripped the Japanese in the aftermath of defeat. Such observations place The Human Condition firmly in the context of its times.

Trailers

The Arrow release contains trailers for each of the three films. Unsurprisingly, they conform to the style of regulation-issue Hollywood trailers. The emphasis is on the stars involved, the money spent, and the locations used in them. They are both deeply comical and unintentionally instructive.

The Human Condition is one of the towering achievements of post-war Japanese cinema. Its cumulative power, fearless honesty, firmness of purpose and elegance of execution cement its status as one of the most incisive indictments of war ever committed to film. Watching Masaki Kobayashi gigantic ambition take shape with the help of Yoshio Miyajima's majestic cinematography is a draining, often harrowing but ultimately enriching and unforgettable experience. The critical momentum pushing this monumental film up the canonical and critical rankings will surely be accelerated by this essential release. All at Arrow deserve our gratitude for ensuring that a film too long hidden from view can now stride forth, once again, to reclaim its place in film history. Highly recommended.

*Archive film footage of the moments captured in Eddie Adams and Huynh Cong Ut's iconic images:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bst9mjjiBBo

**MPPAJ Attendance and Box Office Figures: http://www.eiren.org/statistics_e/

***Screen Anarchy's astute comments on Arrow's release.

http://screenanarchy.com/2016/09/pretty-packaging-arrows-the-human-condition-boxset-gallery.html

|