| |

"For of those to whom much is given, much is required." |

| |

Luke (12:48) |

| |

"Here, ladies and gentlemen, the truth, nothing but the truth on the extraordinary life of Lola Montès." |

| |

The Ringmaster |

| |

|

On a rainy late December night in Paris, 1955, Max Ophüls premiered what would ultimately become his final film, Lola Montès to the public for the first time. The audience was not kind. Rather than rapturous applause, Ophüls got riotous discontent. They had been expecting the epic, grand and sweeping cinematic experiences that had typified his work, but, Lola was not an unknown woman, and there came Ophüls' first problem. Fans promised an entertaining and at least a little scandalous biopic of Lola Montès, the Countess of Lansfeld, played by their favourite star, Martine Carol would come away disappointed. Instead, they are presented with something entirely incomprehensible: an oddity, full of tricks and experimentation, and as a result, incredibly difficult to follow. Though the film would be well received by some critics a few months earlier, François Truffaut and Jacques Rivette amongst them, it would go down as commercial failure, plummeting as fast as Ophüls reputation.

Flash forward over 50 years to 2008, another rainy, but very different night at the 61st Cannes Film Festival. Lola premieres again to a new audience, fully restored as close as possible to director's wishes by La Cinémathèque Française and a multitude of collaborators, including Ophüls son, Marcel, who would introduce the film at the festival. This time, his father's star attraction and swan song, would get that rapturous applause, with critics writing page after page of admiration, lauding it as a lost masterpiece. Max Ophüls reputation as an auteur is cemented, a film far too ahead of its time finally finds a home, and Lola is once again adored by her public, embraced by audiences and critics beyond what Ophüls himself could have imagined.

Just like Lola the star, Lola the film suffered at the hands of fate. Its journey from script to screen as perhaps as well known as its subject matter, and in these days of meta-reference, its easy to that troubled passage being made into a film in its own right, in the mould of The Shadow of the Vampire. Lola was a global super production, filmed in French, English and German with an estimated budget of 8 million deutschmarks. The film was shot over five months, beginning in France and ending in Germany, with a star cast including Martine Carol (Lola) Peter Ustinov (the Ringmaster) and frequent Ophülsian player Anton Walbrook (Ludwig I, King of Bavaria). Despite Ophüls talent – on the rise due to the success of Letter from an Unknown Woman, La Ronde/Roundabout, and his most recent film at that time, Madame de ../The Earrings of Madame de, with large financial backing from German company, Gamma Films, there seemed little that could go wrong.

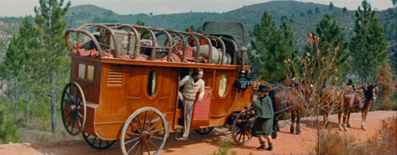

While Ophüls producers had money, they lacked experience. Wanting to capitalise on the current trend of the Hollywood historical epic, they sort out suitable source material, and found it in the real-life figure of Eliza Rosanna Gilbert, better known as Lola Montez, a cabaret dancer and seductress, with equally famous lovers, including composer Franz Liszt and Ludwig I, King of Bavaria. Seeking a director befitting of the transnational scale of the production they were creating, they ultimately hired Ophüls and sought out the popular French novelist Cecil Saint-Laurent to write a novel about Montez, hoping to add to the film's air of prestige, no matter how manufactured it may have been. Ophüls, and latterly co-writer Annette Wademant worked separately from the novel, itself published after the film's completion. It was Ophüls and not Saint-Laurent who had the idea to frame the story in the circus setting, with Lola as the star attraction, the remainder of the film is given over to recounting the rise and fall of Montes in flashback, re-enacted by Ringmaster and his company.

Over time, in order to retain the money he needed to create the picture, Ophüls was forced to make compromises, with the agreement that his artistic integrity would remain intact. Compromise and Lola would ultimately come hand in hand. Never before has any film worn the label 'film maudit' (cursed film) as well as Lola Montès, perhaps only eclipsed in infamy and obstacles by Orson Welles' misunderstood masterpiece, The Magnficent Ambersons. Like Ambersons, Lola films suffered at the hands of the edit table. Upon its disastrous debut, Ophüls was ordered to cut the film in order to garner a more favourable audience reaction, with some scenes removed entirely, others translated and the sound remixed. In late 1956, the film was cut further, against Ophüls' wishes and re-edited into chronological order, thus undoing the non-linear style, more realistic to the process of memory, common in the features the nouvelle vague directors who admired his films, rather than the linear structure of a Hollywood biopic. Later in 1968 and 2002 attempts were made to restore the film to its original form, each progressively closer to the director's intent.* This process culminates in the two years spent by La Cinémathèque Française working from scratch on the frame-by-frame restoration we see on the aptly named Second Sight release.

Was the work, and the wait, worth it? Quite simply, yes.

For a film celebrating its middle age, it certainly does not show it. Their painstaking work has corrected the red-ish hue common to degraded pictures filmed on Eastman colour stock, bringing Lola to her true, vibrant self, bettering how she may have looked to Ophüls as he requested more prints from his colour timer, Jean Gillou, in search of the correct look for the film. The director would surely be pleased with what is presented here – a truly vivid print, full of depth and richness, which truly enhances its look and feel of the film from the first to the last frame. Lola Montès marked Ophüls first feature in colour and in CinemaScope. Though the use of both came at the behest of his producers, wanting an ever grander film spectacle, he turned their constraints to his advantage. Technology had at last caught up with Ophüls' meticulous eye.

Colour, is in many ways, a character in its own right, with specific palettes created for mood and seasonal changes within the flashback sequences, in the style of fellow European melodrama maestro, Douglas Sirk, an is particularly evident during the Mammoth circus set pieces. The usually glittering and decorous Ophüls aesthetic loses none of its glamour in its transition from black and white to colour, and instead gaining a wondrous, kaleidoscopic allure. A particular standout moment sees the Ringmaster, singing an ode to Lola and her newest romantic conquest, lit by phased red, green and blue lights. This is one of many instances where Ophüls asked more of his personnel, with cinematographer Christian Matras breeding invention out of his director's necessity to achieve more. The hard work more than pays off onscreen and makes for a magical, often surprising experience, in the same way the early cinema's experimentation saw it dubbed by film historian Tom Gunning as 'the cinema of attractions.'

What an attraction Lola is. Not only is this a story of love and adulation for a famed star, but it is also a kind of love letter expressing admiration for cinema itself. Ambition and innovation would come to define Ophüls work, and Lola Montès is undoubtedly the director at his creative best. If his cinema could be reduced to a singular hallmark it would be movement. The film's opening, where Lola is bathed in colour, spinning slowly in 360 degrees, like a porcelain doll on a display stand while the Ringmaster delivers his polished oratory is incredibly powerful, transcending the fact that the move is now easily replicated and common to the point of cliché.

Ophüls camera is rarely static and here, stands as a reflection of the hectic atmosphere of both the circus show ring and Lola's lifestyle. Though he openly disliked the wideness of CinemaScope, its vast size showcases the elegance of camerawork, its speed tied to emotion and mood, its sweeping shapes like a Viennese waltz. Rather than be restricted by the format, he chose instead to implement design features which changed the shape and size of the frame – either through masking at its sides or cutting down the space with pillars, gates and curtains. Mostly, these are used to create the illusion of intimacy, but sometimes, amusingly to censor the action, such as Lola's final encounter with Liszt.

Loss, tragedy and unrequited love have been recurrent themes within Ophüls' work, and have plagued his women, whether innocent like Joan Fontaine's Lisa, or vain like Danielle Darrieux's Madame de, none are more plagued and more tragic than Lola, never quite able to maintain the life she aspired to. Her strength ultimately becomes her weakness, when she finally accepts the Ringmaster's offer to join his company, longing for the admiration she once took for granted, feeling the stage is her only place in the world. The film's final moments are its darkest and most poignant, Lola, caged, awaiting the dollar payment of the growing crowds is one of the most memorable in cinema. Like the elephant from the Ringmaster's parable, conditioned to play music to learn to love it, Lola too, knows the circus is beneath her, but used to its routine, can do nothing but endure it. Its sombre resounding note, is of course, that while adulation gave her the life she wanted, it would ultimately be the death of her.

Sometimes, it can be difficult for modern viewing audiences to connect with films from earlier decades, even if they do come from an auteur as celebrated as Max Ophüls. If anything, in our 24/7 celebrity-obsessed culture, Lola's plight holds greater relevance and its carefully constructed social critique hiding within the layers of its deceptively simple rags to riches (and back again) narrative holds an even deeper resonance. The exploration of Lola as a commodity, a person and the relationship between the two are eerily prophetic. Part glamorous fable, part tragic cautionary tale, Lola Montès may have been Ophüls' curtain call, but, he most certainly saved the best for last.

The restoration work done on the film is evident from the opening scene at the quality is maintained throughout. The print is almost spotless and damage-free and the picture quality rather lovely for a film made over half a century ago. The contrast is solid (on plasma TVs it can feel a tad strong in places) and the black levels excellent, while the colours, so much part of the film's fabric, are gorgeously rendered without feeling over-saturated – there's a richness at times that feels almost like golden era Technicolor. The subtitles are fixed, suggesting the transfer was sourced from a print rather than a negative – if so, then it was clearly a top-notch one. The framing is 2.40:1 at the transfer is anamorphically enhanced.

A clean mono soundtrack with a slightly narrowed dynamic range typical of the period but better than many, with no distortion or background hiss.

Working with Max Ophüls: Lola Montès Revisited (79:29)

Directed by Ophüls scholar Robert Fischer, this is a fascinating and detailed look at the production of Lola Montès, from pre-production phase through to completion of the film, and manages to be informative without becoming staid or academically-oriented as I had expected it might. Featuring contributions from key personnel and cast members – shot on various sources and in various decades, conducted by Fischer and fellow scholar, Martina Müller – including co-writer Annette Wademant and Peter Ustinov, with audio excerpts from the late Ophüls, are combined with film clips and copious production stills to give the feel of a retrospective-turned-making-of featurette. This is a treat for fans of the film and the director's work, giving insight into both through warm recollection and amusing anecdotes.

Commentary by Susan White, author of 'The Cinema of Max Ophüls.'

As with the documentary, details are the order of the day here. White provides an incredibly thorough look back at the film, with a focus upon its aesthetic, thematic links to Ophüls work, its historical context, and the editing intricacies of the restoration print - it is well worth listening to from this perspective alone, since the disc lacks any visual record of the restoration process. At times, it can be a little heavy going, but there are few dead spots. White's passion and admiration for Ophüls is clear. This approach certainly elevates it beyond run-of-the-mill commentaries which are defined either by throwaway "Oh, I like this part" comments, in-jokes and/or overabundant praise – a common affliction of some modern commentary tracks. Anyone familiar with White's book on the director will certainly enjoy this, as I did. Perhaps aimed at the knowledgeable cinephile and Ophüls aficionado rather than the casual fan, but it is interesting nonetheless and works much better when listened to after viewing the film again, as opposed to before.

The restoration is undoubtedly the true star attraction here, and Lola has never looked better. That said, the extras package on this Second Sight release are more than worthy of inclusion and are a fine addition to a disc worth the purchase for the restored film alone.

Few films deserve the restoration treatment as much as Lola Montès. This is proof, if any were needed that Max Ophüls remains one of film's most revered directors, whose eye for detail and delicate sweeping camera captured nuances of emotion rarely seen in melodrama. Even though true value of the film has taken its time to appreciate and be appreciated, Ophüls has created many classic gems of cinema, but Lola Montès is most certainly the biggest and brightest jewel in his crown. A fine if long overdue restoration means this film can finally take its rightful place alongside his greatest works. A highly recommended purchase.

|