| |

“You seem rather surrealist. Beware of surrealists, they are crazy people.” |

| |

Jean Epstein to a young Luis Buñuel* |

It may seem odd that one of the most revered film directors of the last century did not have an instantly recognisable visual style. Watch a few minutes of a film by Alfred Hitchcock, Sam Peckinpah, Martin Scorsese, Wes Anderson, Tim Burton, Brian De Palma, Sergio Leone, and a fair few others, and even with the soundtrack muted you should quickly realise who was sitting in the director’s chair. Luis Buñuel, on the other hand, was rarely one for eye-catching camerawork or fancy editing. In his films, they serve the story in an almost fundamental way, an approach that sometimes reminds me of an on-location interview I saw some years ago with Roman Polanski – when asked how he made his directorial decisions, he replied that he simply watched his actors rehearse, and whatever he found himself looking at is where he would then point his camera. And yet watch ten minutes of a Buñuel film and there’s still a strong likelihood that you’ll recognise it as his work, though less for its visual style than for its content and the manner in which it unfolds. It says something that Buñuel is one of the few filmmakers whose name was used as an adjective, albeit one usually applied to single sequences only. It would seem that even almost 40 years after his death, there is only one director able to make a movie that could be described as truly Buñuelian.

Before I proceed, I feel the need to lay my bias on the table. I’ve been a fan of Buñuel’s work since I was first knocked for six by the opening sequence of his 1929 short film collaboration with Salvador Dali, Un chien andalou. If you’ve somehow never seen it and are thinking of giving it a look, then go in prepared, as even close to a century of cinema later, it still has the power to shock an unprepared viewer. A tad ironically, the first feature-length Buñuel film I saw proved to be the last of his career. Then again, the 1977 That Obscure Object of Desire [Cet obscur objet du désir] was the only one of his films that I was old enough to see on its initial release. In the years that followed, London’s independent cinemas enabled me to become acquainted with many of his earlier features, and in the process I became as enamoured with Buñuel’s cinema as so many young American filmmakers of the day were with the films of Howard Hawks. The roots of this began in art school, when I found myself in the thrall of the Surrealist movement and the glorious work that it produced. It’s an artistic love affair that never faded, hence the indescribable thill I experienced when I first encountered Lindsay Anderson’s If….and David Lynch’s Eraserhead. Yet what often distinguished Buñuel’s films is the very thing that can make his visual style seem so restrained and at first glance unremarkable. For me, a key reason that the surrealistic elements of his films are so effective is precisely that they are shot and edited in the manner of a regular drama. There are no camera tricks, no hallucinatory editing, no strange colour tints, just the presentation of the seemingly absurd as if it is everyday reality, which renders it simultaneously disturbing, dreamlike, and often disarmingly or blackly funny. And you’ll find no better demonstration of these traits than his 1972 The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie.

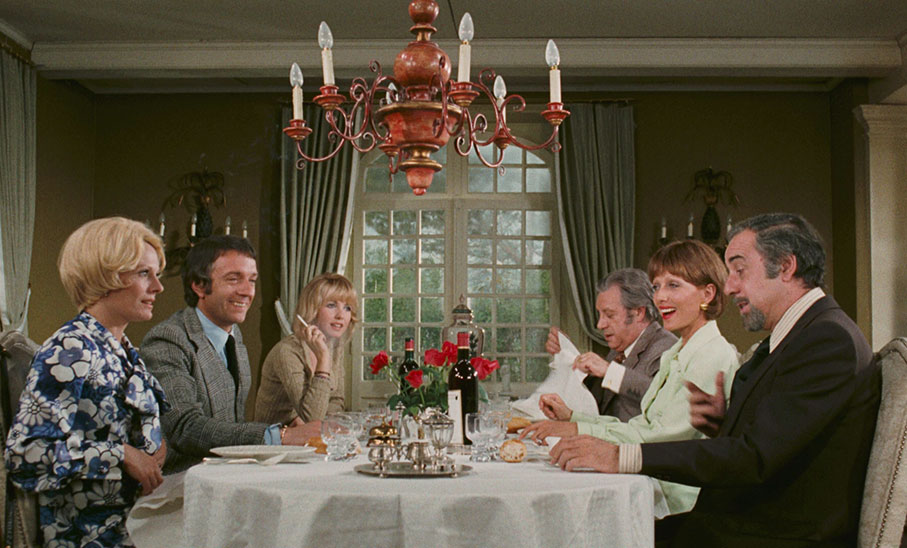

The tone for what is to follow is set in two thematically linked opening scenes. As the titles conclude, four friends – Don Rafael Acosta (Fernando Rey), husband and wife François and Simone Thévenot (Paul Frankeur and Delphine Seyrig), and Simone’s sister Florence (Bulle Ogier) – arrive at the house of their friends Alice and Henri Sénéchal (Stéphane Audran and Jean-Pierre Cassel) for a pre-arranged dinner date. The fact that they roll up the long drive in an expensive, chauffeur-driven car and are formally dressed for the occasion informs us that they are very likely the bourgeoisie of the title, and Don Rafael’s status is emphasised further when referred to as “Your Excellency” by his driver. The door to the house is answered by the Sénéchal’s maid Ines (Milena Vukotic), and the four are greeted warmly by Alice, who descends the stairs in what looks like a nightgown. There’s just one thing – Henri is out at a business meeting, and she wasn’t expecting their arrival until tomorrow evening. It’s a claim disputed by both of the male visitors, who distinctly remember arranging the dinner for tonight, particularly as Don Rafael is otherwise occupied the following evening.

Bemused by this misunderstanding and with no dinner prepared for them to eat, the four friends invite Alice to join them for a meal at a local inn recommended by François instead. When they arrive at the establishment, however, the lights are on but the front door is locked. When François knocks, it is opened by a waitress, who assures him that the inn is open for business but asks him politely to wait. When François demands to see the proprietor, she informs him that the inn has changed hands, and when it looks like the visitors are about to leave, she invites them in. They are shown to a table and have just begun making selections from the menu when a sombre-looking waiter walks through the restaurant and into a small side room carrying two very tall and lighted candles. A short while later, the sound of a woman crying prompts the three women to walk over to the side room to investigate, where they discover the body of the former proprietor lying in state with his weeping widow at his side. The head waiter insists that they can still have an excellent dinner, but while the men seem happy to stay and eat, it’s all too much for Simone and Helen, who insist they leave. And so the second attempt in just one night by this group of friends to enjoy a meal together is cut short even before it has begun. It won’t be the last. This inability of the characters to engage in the social ritual of a shared meal is the recurring event around which Buñuel and his co-screenwriter Jean-Claude Carrière construct their film, one whose story plays increasingly irrelevant second fiddle to a series of encounters, vignettes, and dreams that entertainingly explore and expose the peculiar mores, twisted morality and hypocrisy of the bourgeoisie of the title.

A famed definition of surrealism – one written independently of the surrealist movement but embraced by its members – was coined by Isidore-Lucien Ducasse writing under the pseudonym of Comte de Lautréamont when he wrote of “the chance meeting on a dissecting table of a sewing machine and an umbrella." For me, this is the essence of the surrealist ethos, how everyday objects, actions and encounters can be made to feel subconsciously disconcerting by placing them situations or locations where logic dictates they have no reason to be. Doing so evokes the warped rationality of dreams, where an event or an occurrence that would make no sense in the real world feels completely plausible within the dream itself. If this sensation is successfully evoked on film, it can prompt in the viewer an emotional response that can prove unsettling precisely because it subconsciously reminds us of dream imagery that we are rarely able to recall in any detail once we wake. As I inferred above, it’s made all the more effective in Buñuel’s films by the straightforward manner of its presentation, and characters who react as if there is nothing remotely unusual about things that we as viewers find bizarre. A prime example of this occurs when Simone, Alice and Florence meet for lunch in a crowded café and notice that they are being stared at by the uniformed army officer, who introduces himself as Cavalry Lieutenant Hubert de Rochcahin (Christian Baltauss). Meeting a positive response to be allowed to sit with them, he then tells the story – one shown to us in flashback – of a tough childhood at the hands of his disciplinarian father. On the eve of being sent to military school, he is visited by the ghosts of his late mother and a man bearing violent injuries to his face, who his mother assures him is his true biological father. Acting on her instructions, young Hubert then poisons his familial father’s nightly glass of milk, and as he falls to his death, the father is also visited by the ghosts of Hubert’s dead mother and her murdered lover. When the adult Hubert completes his story, he thanks the women for their time and bids his farewell, and the women promptly return to their conversation as if this tale of ghostly patricide had never been related. The central theme of interrupted meals also figures here, first when the café runs out of tea, milk and coffee, then when Simone has to leave to leave to keep an appointment, which turns out to be an assignation with Don Rafael, with whom she is having a secret affair. This, in turn, is also interrupted when François turns up unexpectedly at Don Rafael’s door, only to be told matter-of-factly by Don Rafael of his wife’s presence, which he accepts without questioning her proffered reason for being in his good friend’s bedroom.

Elsewhere, the surrealism grows – as it sometimes does in real life – from an initial absence of context for actions that seem peculiar or irrational in isolation, only for their motivation to then become clearer, if not always completely rational. A prime example occurs the morning after the first two abandoned meals, when Don Rafael – who is revealed to be the ambassador for the fictional South American Republic of Miranda – is visited at his office by François and Henri. Whilst there, François notices a young woman (Maria Gabriella Maione) in the street below who is attempting to sell cute clockwork animals to passers-by. On hearing this news, Don Rafael walks calmly to a cupboard, takes out a rifle, opens the window, and takes aim at the girl. It feels like a completely irrational move, one that plays a little like a trial run for the extraordinary tower block sniper sequence in the director’s next film, The Phantom of Liberty. Even François and Henri seem startled by it, and while the realisation that Don Rafael is aiming instead at one of the clockwork toys dials the extremity of his action down a notch, an inescapable air of irrationality remains. But after he shoots one of the toys (that it’s a small animated dog leaves even this small detail open to secondary reading) and the girl beats a brisk tactical retreat, Don Rafael reveals that she is part of a Miranda terrorist group that has been trying to assassinate him, and his move was clearly designed to frighten her off. A later encounter between Don Rafael and the same woman develops into a commentary on the imbalance of power between their two social classes and political ideologies, as he holds her at gunpoint, feels her up whilst frisking her for weapons, then condescendingly offers her a glass of champagne that she defiantly empties and smashes. When she is unexpectedly permitted to leave, any whiff of charity on Don Rafael’s part is promptly dashed when he signals waiting agents, who grab her and bundle her into car as soon as she exits the building. This reversal of the movie norm – where motivation or reasoning is provided before action is taken – puts an intriguing spin on even simple gestures that only make complete sense in retrospect or on a second viewing. A personal favourite occurs in opening scene as the visitors arrive at their friends’ house. As they wait for the door to be answered, François turns to Florence and wags his finger at her in smiling admonishment, an action that prompts an amused response from everyone but her. On a first viewing, this feels peculiar, but once we realise that Florence is a bit of a booze hound and cannot hold her drink – at one interrupted meal, it only takes only a couple of dry Martinis to have her heaving out of the car window as the guests prematurely depart – this friendly finger-wag of warning makes complete sense.

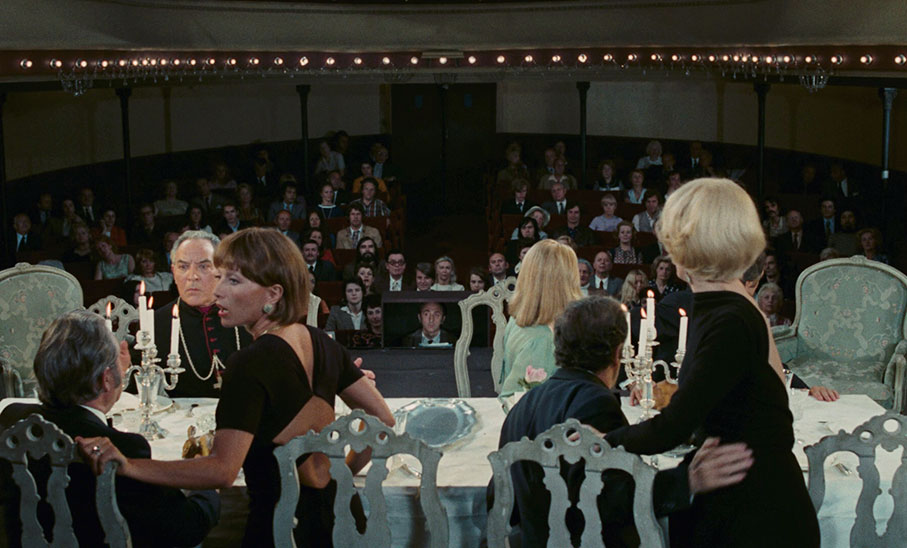

As the film progresses, further attempts by the group to enjoy a meal together are disrupted in increasingly unexpected and creative ways. One arranged luncheon ends up being abandoned before it starts because hosts Henri and Alice are overcome by sexual desire at the very moment their guests roll up at their door, and instead of going downstairs to greet them they sneak out through the window and off into the woodland where Alice’s cries of passion will not be overheard. An evening meal at the same location at a later date actually gets under way, then is loudly disrupted by the day-early arrival of a company of soldiers that Henri has agreed to billet whilst they are on manoeuvres. When their training session is launched far earlier than expected, it proves loudly explosive enough to make any dinner conversation close to impossible, though not before everything is put on temporary hold so that one soldier can tell everyone about his dream. Things complicate further for the characters and first-time viewers when more bizarre subsequent disruptions turn out to be dreams, all of which initially play as next-scene reality because no clues are provided by the consistency and continuity of the cinematic style. It’s a sly bit of audio-visual deception that peaks when one dream is revealed to be nestled inside of another, a neatly executed trick that would later be borrowed by John Landis for An American Werewolf in London and subsequently become a bit of a horror trope.

Elsewhere on this disc, French critic Charles Tesson claims that Buñuel was primarily interested in the political dimension of surrealism, and you’ll find plenty of evidence in support of that view here. That Don Rafael and his fellow bourgeoisie are corrupt to the core is established early on when he opens his diplomatic bag and unloads several bags of heroin that his position has enabled him to smuggle into the country for François and Henri to purchase and resell. Later, questions are asked of him by others that suggest the Republic of Miranda is a deeply corrupt fascist state, and that Don Rafael is an amoral oppressor. At one point, he casually compares protesting students to flies, and with a casual gesture suggests that when you have an infestation of flies, you wipe them out. By now it’s becoming clear that Don Rafael’s definition of a terrorist is another man's freedom fighter.

The expected Buñuel digs at the church are there in the shape of Monsignor Dufour (Julien Bertheau), a local bishop looking to join the ranks of working priests by taking up the vacant position of Alice and Henri’s gardener. His timing is impeccable, arriving whilst the couple are making love in the woodland and just as their guests are beating a hasty retreat, having misinterpreted the disappearance of their hosts as evidence that the police are onto their heroin-smuggling scheme. Dufour is greeted instead by Ines, then investigates the grounds and becomes so fired up at the prospect of becoming the gardener that he changes into the appropriate attire and starts work. When he returns to the house to introduce himself to Alice and Henri, he is taken for a lying vagabond and unceremoniously thrown out. Later, the Catholic notion of forgiveness is savagely mocked when Dufor is asked to give the last rites to a dying man, a seemingly simple service that tests the bishop’s true commitment to the teachings of his faith.

Much has already been written about The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie, which is understandable given how much is worthy of discussion and analysis in this extraordinary and multi-layered film. Indeed, I have a feeling that if the release date of this disc was not already almost upon me, I’d be deconstructing every scene, every character, and probably every moment until summer had long since faded. It’s one of those rare films whose every component works on multiple levels, weaving a barbed critique of the bourgeoisie beautifully into a consistently compelling but virtually plotless whole that is run through with a smart and intermittently laugh-out-loud streak of blackly surrealistic comedy. The performances are consistently divine across the board, with even the smallest roles registering because they have been cast with such care and given memorable traits or little bits of business. These range from the telling glance that the candle-carrying waiter throws directs towards the women at the inn, to the woman who requests that Dufor read the last rites to the dying man and then inform him that she has hated Jesus since she was a child.

For a newcomer, The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie a film chock full of surprises and unexpected delights, and even all these years after I first fell in love with it, I was genuinely bowled over by how fresh and busy with incident and invention it still feels. Everything about it works sublimely, and even the famously bemusing shots that randomly appear of the six friends walking down a wide open country road do not feel at all out of place, despite having no direct connection to any of the scenes that surround them. Like so much in the film, they seem deliberately open to audience interpretation – an image of the bourgeoisie on a road to nowhere, perhaps? – but it’s always possible that the ever-playful Buñuel was amusing himself by laying a trap for critics with an image that has no specific meaning. It’s an intriguing, suggestive and perhaps deceptive element of a film that is crammed to the brim with such detail, and collectively makes for one of the finest works by one of the most entertaining, imaginative and gifted provocateurs in all of world cinema.

The result of a new 4K restoration by Studiocanal, this new 1.66:1 1080p transfer is a major improvement on the one found in the distributor’s seven-film Blu-ray box set from 2017. I’d argue that The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie was the black sheep of the set, saddled as it was with an overly bright image and some very visible and unattractive edge enhancement. This new transfer rights both of these wrongs, as although the picture is noticeably darker, this is because it has been more correctly graded, resulting in a far more pleasing balance and range to the contrast. Where the previous transfer made the film at times looks almost as if it was lit for 1970s American television, here the lighting looks far more naturalistic and artistically pleasing, with bolder shadows, well-defined highlights and solid black levels. The film's earthy colour hues have been retained and a slightly more pronounced here, and the stronger colours a little moire vibrant. The edge enhancement of the previous release has also been banished, resulting in a naturally crisp image where film grain is still visible but not digitally boosted as it was before. This new transfer also includes slightly more picture information at the top and on both sides of the frame. I've inccluded an image for comparison below, but should note that the difference is far more pronounced on my TV screen than it is on the frame grabs.

The 2017 release (above) compared with the 2022 restoration (below)

The original French language mono soundtrack is presented as DTS-HD 2.0 and I’m guessing this has also been restored, as it definitely feels a little more refined than its predecessor. As expected, it is free of damage and wear, and the dialogue is always clear, except when deliberately drowned out by the cleanly rendered sound effects.

As with the previous release, English and German language tracks are available, both of which are distracting dubs that lose all of the nuance of the original track, as well as robbing these talented actors of a key aspect of their performances.

Optional English and German subtitles have also been included. If you select English as the default language when you insert the disc, the film will play with French audio and English subtitles, but this can be changed at any time.

Critical Analysis by Professor Peter W. Evans (34:14)

Peter W. Evans, Emeritus Professor of Film Studies at Queen Mary University of London, outlines briefly how Buñuel became a filmmaker, then explores what he describes as the director’s most dream-conscious film. There’s some really interesting analysis here, including a detailed breakdown of the five dream sequences, and discussion on the autobiographical touches, the concept of repetition and how this was developed into the final screenplay by Buñuel and Jean-Claude Carrière, the notion of people who live by rules that they then fall foul of, the comical elements, and more. There is one thing. Early on, Evans states that Whit Stillman’s 1990 Metropolitan was inspired by this film, and I’m going to have to take issue with him on that score. On the commentary track of the Metropolitan DVD, Stillman states that his film was inspired by the experience of hanging out with the very sort of people that are featured in the film and unexpectedly getting to like them. Later in the same commentary, he claims that he only saw The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie during the course of his research, and judging from the groans he and his fellow commentators emit, they were not fans. This is presented in standard definition and was also featured on the previous Studiocanal Blu-ray of the film.

Interview with Writer Jean-Claude Carrière (24:22)

Also carried over from the previous Blu-ray is this hugely valuable interview with the film’s co-screenwriter Jean-Claude Carrière, a regular Buñuel’s collaborator who sadly died in February of last year at the age of 89 with over 150 writing credits to his name. He talks about Buñuel’s originality, the origins of the story for The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie, the evolution of the title, producer Serge Silberman, the role of repetition in Buñuel’s cinema, his long-standing working relationship and friendship with the director, and more. An essential watch.

Trailer (2:56)

This is not an easy film to promote in three minutes of screen time, something this original French trailer inadvertently acknowledges by stringing a series of almost randomly chosen clips together in the hope of capturing something of the film’s dreamlike non-narrative. I’m not sure it succeeds. It includes the famous legs, lips and bowler hat poster image that Buñuel himself is reported to have detested.

Analysis of 3 Scenes of the Film with Critic Charles Tesson (19:45)

French critic Charles Tesson provides a commentary on three sequences from the film: the opening meeting at the Sénéchal house; the arrival at the inn and the disruption of the meal that follows; and a later dream sequence that takes place on a theatre stage. There is some interesting analysis here, particularly on the theatre scene, but a little too much of it involves Tesson describing what’s unfolding on screen or what any observant viewer should be able to deduce for themselves. Still intermittently of interest, however.

Critical Analysis of Charles Tesson (31:05)

Here, Tesson provides a more comprehensive appreciation of the film as a whole, echoing Jean-Claude Carrière’s words on the conception and the writing of the screenplay, and providing some interesting and enthusiastic analysis of individual elements. These include the role of ritual and repetition, the fact that it’s only the male characters who dream, the suggestion that the women in the café scene are nourished by a story instead of food, the conflicting notions of civilisation and violence, Buñuel’s rarely discussed camerawork, the excellent performances, and more.

New Trailer (1:12)

A far shorter trailer than the one detailed above, prepared for this new restoration of the film. While also compiled from disconnected shots from a range of sequences, for me this gives a better flavour of the film’s varied content and unexpected diversity than the earlier trailer.

Luis Buñuel is a filmmaker whose work I find it nigh-on impossible to remain objective about when discussing in any detail, in part because when I watch one of his films it seems so specifically tailored to my taste that I almost feel like he made it just for me, a notion quashed by the high regard in which he and his body of work is still held. The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie remains one of his most most popular and successful works (it even won an Oscar, something Buñuel was always dismissive of), but is also one of his most entertaining and perfectly formed. The new 4K restoration on this Blu-ray is a marked improvement on the previous Blu-ray release, and while lacking one of that disc’s special features, it does include new contributions from Charles Tesson. If you’ve not yet made the move to UHD, then this Blu-ray comes highly recommended, but the fact that there is a simultaneously released 4K edition will likely make that the one to go for if you are able to play it. I was sent the Blu-ray for review, but I’ve ordered the UHD anyway and will update the sound and vision specs above when I’ve had the chance to compare it. For now, the Blu-ray comes highly recommended.

* https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Luis_Buñuel

|