"The soil of Burma is red, and so are its rocks." |

Opening Caption of The Burmese Harp |

The difference, one could argue, between a good war movie and a good wartime action movie is that the former focuses on the reactions, emotions and fate of those involved in the conflict, while the latter is more concerned with the big bangs and gunfire. In an action movie, an explosion is usually a means to an end or a pyrotechnic thrill, but a decent war movie will take time to explore its effect on those who suffered its consequences and even those who triggered it. Which is why Where Eagles Dare, with its endless supply of trip-wire bombs, insane body count and unflappable heroes, is an action movie through and through, and why Elem Klimov's 1985 Come and See [Idi I smotri], whose young central character spends twenty real-time screen minutes half-deaf and shell-shocked from a forest bombing raid, is a war drama par excellence. If you're looking for wartime fun and thrills then you'll do no better than Where Eagles Dare, but if you want to explore the human effects of war in a soberingly realistic manner, then Klimov is your man.

Of course just how war is portrayed on film can depend very much on when and even where it was made. During WW2 the studios of all participating nations were encouraged and indeed committed to producing works that supported the war effort of their respective countries. It was only some time later that filmmakers were able to suggest that patriotism sometimes took second place to self-preservation for those on the front line, and that war and its consequences, both physical and psychological, really could be hell. For some this meant coming to terms with their own combat experience, something vividly demonstrated by Samuel Maoz's recent Lebanon, while occasionally it becomes part of the healing process for the nation as a whole.

Such was the case with The Burmese Harp [Biruma no tategoto], a 1956 film adaptation of the celebrated 1948 novel by Takeyama Michio, a writer who openly opposed Japan's tripartite alliance with Germany and Italy during WW2. It proved an important film for a number of reasons: it was a huge hit on home turf; it won a major prize at the Venice Film Festival (where it was also nominated for the Golden Lion, the festival's top prize); and landed a nomination for Best Foreign Language Film at the 1957 Academy Awards, bringing its hitherto unknown director Ichakawa Kon to international recognition. It also humanised the ordinary Japanese soldier to an international audience who had previously seen them largely as death-or-victory fanatics to be killed rather than reasoned with. For the domestic audience it both portrayed and accepted the Japanese in defeat, confronted their losses, and dared to suggest that in extreme circumstances, fighting to the last man was a poor alternative to surrender.

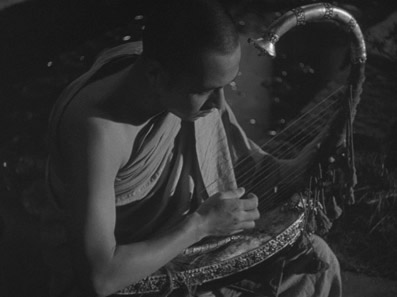

The film begins in the closing days of the Second World War, as an exhausted and dispirited Japanese army regiment rest up in the Burmese jungle. To raise their spirits, their leader Captain Inouye (Mikuni Rentarô) begins singing a traditional song, accompanied by the self-taught Mizushima (an impressive Yasui Shôji) on a hand-made Burmese harp. One by one the soldiers join in, and the following day are back on the march, strengthened by the music and the camaraderie it has inspired.

For those well versed in western war movies, this may well prove a slightly disorientating opening. It's a familiar scene, one you'll find a good many British and American war films of the period, but it usually occurs far later in the story, when we've spent time with the characters and watched them being beaten down by the hardships of battle. This is usually the point, about two-thirds of the way through, when everything seems hopeless, and a harmonica is produced and the group sing a song that reminds them of home, the nostalgic calm before the climactic storm. And yet here it is, right at the start, and playing out as if we've spent a good hour in the company of the faces on which we are invited to gaze. But as a short-cut to character engagement it's surprisingly effective, despite our unfamiliarity with the individual soldiers, and we soon learn to care for their fate as a result.

The next day they rest up in a Burmese village, and despite being greeted with expressions of stony hostility (a little historical knowledge is useful to understanding why), they are treated to a song by its seemingly hospitable occupants. They're about to respond with a tune of their own when the villagers depart with troubling haste. The soldiers quickly realise that they're surrounded by the British and that there's a wagon packed with ammo sitting in a dangerously exposed spot, something they retrieve with the sort of ballsy creativity you tend to associate with western POW movies. These Japanese soldiers are not just sympathetic, they're resourceful too. Trapped without an escape route, they break into song, this time the internationally recognised Home, Sweet Home. So heartfelt and melancholic is their singing that the encamped British are soon joining in. Music has become, albeit temporarily, a unifying force for peace.

The war is over and the Japanese surrender (perhaps significantly, the act itself is never shown), and in the spirit of their new cooperation, Inouye agrees to help the British (who appear to be largely Australian if their accents are anything to go by) by convincing a group of Japanese soldiers holed up in a mountain cave to surrender, his principal concern being to avoid further unnecessary fatalities. Mizushima is selected to carry out the task, but the entrenched company react with hostility to his request and elect instead to fight to the death. The sole survivor of the subsequent firefight is the seriously injured Mizushima, who is nursed back to health by a Buddhist priest. His strength restored and disguised in the priest's robes, he begins the long trek to rejoin his comrades, an experience that prompts an unexpected and life-changing spiritual awakening.

There are plenty of things here that by all rights should neuter the film's noble intentions, from the bonding power of communal singing to the transformation of Mizushima from soldier to Buddhist monk in a disguise he will later inhabit by choice. The group singing repeatedly runs the risk of tipping the film into sentimentality – Home, Sweet Home is an emotive tune (its use at the end of Takahata Isao's 1988 Grave of the Fireflies is emotionally devastating), and when the regiment are joined in song by their British counterparts, it feels almost as if the two sides are on the brink of discarding their differences to form a brotherhood of soldiery based on cooperation rather than conflict. If that makes the whole thing sound unbearably sappy then be assured that it's not – Ichikawa walks a delicate line here, his use of facial close-ups comparable to the memorable final sequence of Paths of Glory (which also revolves around soldiers and the unifying power of song), and he cannily concludes the scene before overplaying its effect.

The specifics of Mizushima's spiritual awakening, meanwhile, are handled with admirable and sometimes sobering restraint, from the simple gifts of food from passing peasants to the small mountain of corpses of Japanese soldiers that he abandons reunification with his comrades to bury. His story is made all the more intriguing by the non-linear manner in which it unfolds, the assumption that he died in the mountain bombardment only called into question when the regiment pass a monk who bears a striking resemblance to their supposedly fallen comrade, whose journey to this point is then revealed in narrative flashback.

Mizushima's post-recovery refusal to engage in vocal communication adds an element of mystery to his motivation and purpose. When he does speak it's through his distinctive way with the harp of the title, which is at its most potent in a sequence whose specific meaning will likely be lost on a western audience (skip to the next paragraph to avoid a spoiler) – the last tune he plays to his former comrades is a well-known Japanese song of goodbye, one sung at school graduations by departing students in the sad realisation that they may never see each other again.

Exquisitely shot in monochrome by Yokoyama Minoru (Ichikawa apparently wanted to shoot in colour but considered Nikkatsu's bulky three-strip cameras too heavy for location work), whose images range from intimate close-ups and captivatingly framed group shots to striking location work in Burma and southern Japan. Occasionally the imagery is genuinely haunting, as in the wide shot of the killing ground shore where Mizushima boards a boat to continue his journey, where the grey of the mud seems to meld with the water it borders. It's a similar story when he returns to bury the fallen soldiers, where he is watched by four initially motionless locals, silent witnesses to his transformation who, in one of the film's most powerfully understated moments of reconciliation, eventually step forward to help with his task.

The Burmese Harp is post-war humanist film drama at close to its best, one that movingly explores the consequences of war and the process and self-healing without feeling preachy or unduly sentimental, despite ample opportunity to sink into both. Its focus on character and the universality of key story elements make its international success seem less surprising in retrospect, while the confidence and storytelling skill of its director make it feel only right that it brought him the recognition and acclaim that it did, despite the fact that his earlier Kokoro should by all rights have done likewise. There's far more to the film than the above summary might suggest, in character detail, symbolism, religious allegory and suggestive layering (there is even a point at which I began to suspect that Mizushima did not survive the bombardment and had remained on earth as a wandering spirit), and it remains one of the great pacifist works of the post-war period. Its success paved the way for Ichikawa's subsequent and often notable body of work, including his 1963 An Actor's Revenge [Yukinojô henge], one of the boldest and most visually striking films in his long and distinguished career.

It's worth nothing that the film was originally released in two parts whose combined running time was twenty minutes longer than the version on this disc. But don't feel short-changed – the footage was cut by Nikkatsu when they combined they two halves into a single film and is now believed to be lost, making this the most complete version currently available.

Another of Masters of Cinema's Blu-ray only releases, The Burmese Harp is not as eye-pokingly lovely looking as the distributor's previous Profound Desires of the Gods, and indeed boasts a generally softer contrast range than that found on the Criterion DVD release, though this does help preserve shadow detail that would likely be lost if the contrast was boosted. In many of the daylight exteriors this still results in a very pleasing tonal range and solid black levels, which hit an eye-catching peak in the location work at the Burmese temples. It's also there that the increased level of detail offered by Blu-ray is at its most obvious, though this is clearly visible throughout the film, in facial close-ups, foliage, architecture, and the texture and patterns of clothing. The odd small scratch still remains, but otherwise the print is remarkably clean.

The source material used for the disc was an HD master provided by Nikkatsu from the Japanese theatrical release, which includes Japanese subtitles for the Burmese dialogue, which appear vertically at the frame sides and do not clash with the optional English subs. This also clearly indicates to non-Japanese speakers when Burmese is being spoken. This is, apparently, the first time the original Japanese print seen by domestic audiences has been released on home video outside of Japan.

Despite an inevitably narrowed dynamic range and some detectable background hiss, the DTS-HD Master Audio 2.0 mono track does well for its age, boasting almost no distortion even with cheering or music.

Tony Rayns on The Burmese Harp (18:13)

A typically excellent introduction to the film by the learned Mr. Rayns, who explains the background to Ichikawa's involvement and the effect of its success on his subsequent career. He also talks about the original novel and the changes made for the film version, the casting, the decision to film in black and white, the locations, the original running time, and more. Although not labeled on the disc as an introduction, there are no spoilers here and it's safe to watch this before the film if you choose.

Original Japanese Trailer (3:41)

A long trailer that reveals way too much of the story to be safely watched just before the feature. Interestingly, the contrast is a little stronger here than on the main feature and looks OK on it, though the boat-boarding shot mentioned above does loose a little of its otherworldly poetry.

Booklet

The bulk of this typically fine MoC booklet is made of of a detailed essay on the film by Keiko I. MacDonald, which I'd definitely save until after you've seen the film and made your own judgements about the characters and themes. Also included are a number of quality stills, credits for the film, a reproduction of the original poster and details of the transfer.

A heartfelt and genuinely moving story of post-war trauma and healing, captivatingly told by a sometimes undervalued director at close to the top of his game. As for the transfer, well the film's age may show in some contrast variance, but there's a tonal beauty and crispness of detail to many scenes that once again justifies the Blu-ray release. Warmly recommended.

The Japanese naming convention of family name first has been used throughout this review.

|