|

There's something about a solitary feat of physical endurance that can't help but capture a nation's imagination. Take yachtswoman Ellen MacArthur, who in 2005 broke the world record for the fastest solo circumnavigation of the globe, an accomplishment that brought her instant (if short-lived) celebrity status and made her the subject of nationwide coffee-break discussion. Her tearful video diaries of the trip become famous enough to be the subject of parody, and her achievement saw her made a Dame Commander of the Order of the British Empire at just 29 years of age. None of which should be that surprising. We British, like many nations, regard such achievements not as the product of individual effort but the country in which that individual was born. It's hard not to get just a little caught up in it. Even I, with my inbuilt cynicism and complete disinterest in sport, found myself enjoying just the teeniest buzz at the news of all those British gold medal wins in last year's Beijing Olympics.

And yet in 1962, when 23-year-old Horie Kenichi completed the first solo sea voyage across the Pacific Ocean from Osaka to San Francisco, a journey undertaken on an unpowered boat by a young man with little in the way of previous sailing experience, the reaction in his home country was apparently one of widespread dismissal and even shame. In the Japan of the time, the collective belief was that no individual should disrupt the harmony of the whole, and by secretly embarking on such a quest without obtaining official permission, Horie's actions were seen not as heroic but a those of a criminal madman. It's a mark of the difference between the two societies at that time that in America Horie's achievement was widely reported and celebrated, and although initially arrested for having no passport, he was quickly freed by San Francisco's mayor and given a 30-day visa and the key to the city.

On his return to home shores, Horie wrote a book about his adventure, which the following year was adapted into a feature film by writer Wada Natto and director Ichkawa Kon, who together had just completed An Actor's Revenge [Yukinojo henge], one of the most striking Japanese films of the period. Alone Across the Pacific [Taiheiyo hitori-botchi] apparently caught the imagination of the Japanese public in a way the event it depicted had not. Perhaps it was due to the presentation of the story in a format more readily associated with adventure and fiction. A Japanese friend who grew up with the cinema of this period has suggested it had more to do with the central casting of Ishihara Yūjirō, an actor admired by men and adored by women, in part for his tendency for playing characters who would chase after their dreams in defiance of the rules and disapproval of society. Exactly what Horie had done in real life, then. Oh, the irony.

This cultural background to the story is hinted at in the film's bookends, as Horie sets sail in the dead of night from Nishinomiya harbour with the hope that he will not be apprehended in Japanese waters (at that time small craft were forbidden to leave the country without official authority), and in a final scene in which his father tells a press conference in all sincerity that he will ask his son to apologise to everyone on his return. The bulk of the film, however, is occupied by the journey itself, whose one-man-in-a-boat story is broken up by flashbacks to Horie's preparations for the journey and his conversations with family members regarding his intentions. It's an approach that Brent Kliewer, in an essay in the booklet accompanying this very DVD, describes as being as daring as the venture itself, which turns a curious blind eye to the fact that this very structure was employed by Billy Wilder six years earlier to tell the story of Charles Lindberg's solo transatlantic flight in The Spirit of St. Louis. Which should in no way detract from Natto and Ichikawa's achievement in constructing a gripping narrative from a story whose main character spends a three month period in isolation from human companionship.

Like Wilder before him, Ichikawa employs the trick of having his protagonist talk to himself, both to break up the silence and keep us clued in on the condition of his craft and mental state. Any gaps are patched by Horie's voice-over, which retrospectively keeps tabs on the journey's progress. Both techniques have their logic here, given that the film is adapted from a first-person narrative written by a character who even in family flashbacks appears locked into his dream. The flashbacks themselves benefit from their non-linear nature, disparate jigsaw pieces that eventually and collectively contribute to a satisfyingly textured whole. It also helps that Ishihara so convincingly sells Horie as a little man driven more by obsession than ambition – dressed in his everyday work clothes, he seems almost charmingly dwarfed and misplaced on his arrival in San Francisco, a sensation enhanced by his innocent bewilderment at the attention he attracts.

The ninety-seven minute running time and economic narrative progression keep the story moving at an engrossing pace, but do so at the expense of any deep exploration of the loneliness and sense of complete and even helpless isolation that anyone undertaking such a venture must inevitably suffer. It's left to individual episodes – a flood of therapeutic tears, concerns over the dwindling water supply, the extreme difficulty of navigating the small boat in a storm, his repeated sea-sickness – to give us a flavour of Horie's hardship, some of which inevitably recalls Thor Heyerdahl's six-man Pacific crossing on a balsawood raft as recorded in his own 1950 documentary record Kon-Tiki.

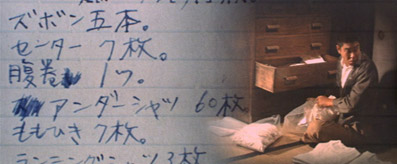

Cinematically, however, the epic nature of the trip is most effectively communicated, with Horie and his craft dwarfed in the surrounding seas by Yoshihiro Yamazaki's scope cinematography and intermittently isolated within a darkened frame in a manner also employed (though to more surreal effect) by cinematographer Setsuo Kobayashi in Ichikawa's previous film An Actor's Revenge. Individual scenes are also particularly memorable, none more so than the inventory of supplies collected for the trip, given arresting visual representation by a split-screen image of a scrolling packing list (which the subtitles have no chance of keeping up with, particularly as they also have to cope with a simultaneous voice-over) alongside footage of the items in question and Horie's preparations for the journey. It's one of those sequences that on paper you can't see holding your attention for the four and a half minutes it runs, but is one of the most perfectly realised in the film.

It may be tough to make a case for Alone Across the Pacific as a genuinely great movie – even enthusiastic supporter Brent Kliewer describes it as "one of the most curious oddities in the director's oeuvre" – but I'd still argue that it's a very fine drama whose historical importance comes as much from what you can read between the cultural lines as its record of Horie's bold adventure. It's in the family flashbacks that this is most evident, particularly the resigned disapproval of both of Horie's parents, a conflict of emotions most effectively caught when his mother (played with touching subtlety by veteran actress Tanaka Kinuyo) is forced to accept her son's decision to go, but tells him, "If you're caught in a storm and facing certain death, call out to your mother." Although immediately cut away from and accompanied by no reaction shot, it's a line that touches on a number of cultural and dramatic elements, and one that lingers over the remainder of Horie's voyage.

Framed 2.40:1 and anamorphically enhanced, the transfer here has clearly undergone considerable restoration, evidenced in the almost complete absence of dust and damage, though the source print appears to be a few notches shy of perfect. The detail is very good and the colour palette, although muted for much of the film, springs to life when brighter colours are introduced (the red cushion given to Horie by is sister or the sunset shot are good examples). Contrast is generally solid, but does slip a bit on some of the darker scenes and where black is used to isolate one portion of frame. On the whole, though, a very nice job.

The Dolby mono 2.0 soundtrack is clean with a little crackle just popping up here and there. The dynamic range is inevitably restricted, with some slightly crisp trebles and a little distortion on some louder sounds. Otherwise fine.

The English subtitles are clear and well translated, although sometimes very Anglicised – at one point Horie passes comment on his situation by saying "What a palaver!" Being sourced from a Japanese print, there are fixed Japanese subtitles for the English language dialogue.

Three trailers are included and are all in sparkling shape. The Japanese Trailer (3:42) is a small production in itself and claims that the film "pushes the boundaries of modern cinema" and was "shot by the finest crew in the Japanese film industry." Which may well be true, of course. There are also two Teaser Trailers (2:45 and 1:38), the first of which is almost as long as the main trailer, though it does point out that this was the first Japanese film to be even partly shot on American soil. It includes footage of lead actor Ishihara (affectionately referred to here as Yu-chan) being transported to American on a Pan-Am flight and relaxing on Waikiki beach in Hawaii, where the camera tilts down to show his Pan-Am bag (the American involvement in the production is rather heavily emphasised). The second is shorter but rather delightfully describes the film as a "dazzling symphony for youth, ocean and yacht."

Also included is the usual Masters of Cinema booklet, which includes film and DVD credits, a two-page article on actor Ishihara Yūjirō by Tony Rayns and a substantial essay on the film by Brent Kliewer.

A fascinating and enjoyable recreation of a remarkable true story (although a little artistic licence has apparently been taken with the flashbacks) that certainly marks something of a diversion for Ichikawa after An Actor's Revenge. It's a film that would probably have remained largely unseen in the UK were it not for the efforts of those fine people at Masters of Cinema (at the time of writing there's not a single IMDb user comment on the film, though that will surely change once the disc hits the stores), and this is exactly the sort of release that makes this label such a precious thing for film lovers. Recommended.

For the record, this was far from Horie's only solo seafearing adventure. You can check out his many other achievements in this arena through his Wikipedia page here.

The Japanese convention of surname first has been used for all Japanese names.

|