| |

"That’s exactly what the company wants, to keep you on the line. They’ll do anything to keep you on their line. They pit the lifers against the new boys, the old against the young, the black against the white, everybody, just to keep us in our place." |

| |

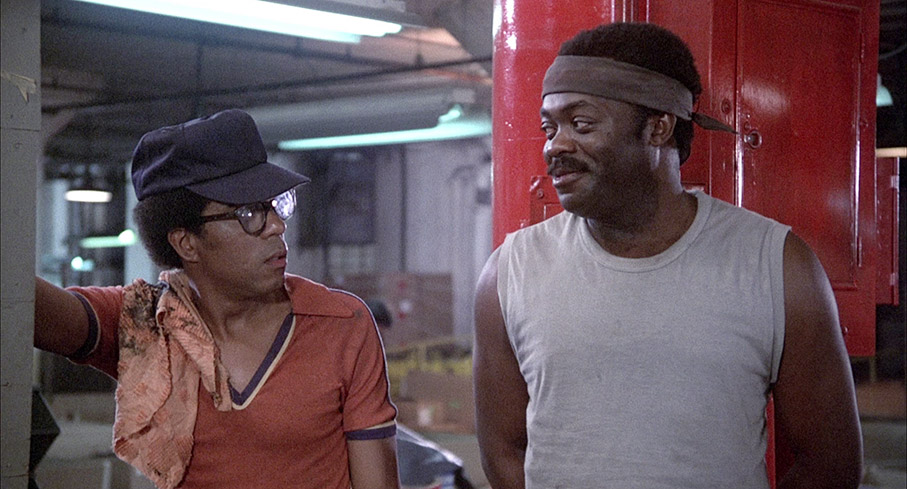

Smokey James |

In the once famous words of The Strawbs (I'm sure I've lost more than half of you right there), I'm a union man, and have been for most of my working life. I've also been a union workplace rep for over twenty years, and have stood on my share of picket lines to protest government cutbacks and attempts to strip away hard-won rights. I strongly believe that a trade union presence is important in any workplace, and not just for the support and protection it offers its members. When you have a good dialogue between management and the union, you have a mechanism for dealing with issues in a manner that can and often does prove satisfactory to both parties and prevent simple misunderstandings escalating into all-out war. At least that's been my experience. As more and more young workers find themselves exploited under what has become known as the gig economy, the need for workplace unions is as urgent as ever, but unscrupulous employers are still actively blocking unionisation, and for many of those coming into the job market now, the very concept of workplace unions is almost an abstract one. Just recently, I was outlining the advantages of trade union membership to one new young member of staff, and his response was telling: "It sounds really good, but I'm not planning to be here long, so it doesn't seem worth it." Of course, these are the very people who a few weeks later are knocking on my door with that all too popular opening plead, "I know I'm not in the union, but..."

The British right-wing press still likes to demonise trade unions, primarily because they represent a threat to a balance of power that considerably advantages the sort of obscenely wealthy individuals who own newspapers and media organisations. Their oligarch editors like to wail about the dark days of the winter of discontent and the heated conflict between striking miners and the Thatcher government, and still paint a wearily one-sided picture of both. Then again, that's all they've really got to throw at us. In America, it's been a slightly different story. The fight for workplace rights and a living wage has been as hard fought there as it has here and, in many ways, it's been a considerably tougher battle. Check out Barbara Kopple's superb documentary, Harlan County U.S.A., which chronicled the conflict between striking miners and the owners of the Eastover Mining Company in Harlan County, Kentucky, for a sobering insight into the sacrifices that workers have made for the sort of basic rights too many of us now take for granted. But even the most passionate defence of American trade unions gets into trickier territory when it comes to past links between certain unions and union leaders to organised crime. The primary goal of any union should be to protect and enhance the welfare of its members, and if union's funds are being misused and its organisers are rechannelling their efforts into racketeering, the ones who lose out are the very people they are supposed to be representing.

It was in the course of talking to factory workers when researching a new film that Taxi Driver scriptwriter Paul Schrader first encountered the consequences of this corruption in the shape of production line workers who had become as contemptuous of their union as they were of management. Out of this grew the 1978 Blue Collar, which Schrader co-wrote with his brother Leonard and which also marked his move into the director's chair. It's an auspicious debut and a commercially risky one, and despite the near-universal critical acclaim with which it was greeted and my own very vocal enthusiasm for it, it remains a criminally unseen and too rarely discussed example of American 70s political cinema at its rare and brilliant best.

It begins with one of my very favourite opening title sequences, as the camera prowls the assembly line of a Detroit auto plant to the pounding, hammer-on-steel blues beat of Captain Beefheart growling his way through score composer Jack Nitzsche's Hard Working Man. Intermittently the action freezes and the music is stripped back to the bare bones of its metal-on-metal beat. It's in these metallic heartbeat pauses that the credits unfold. I first saw the film on its original cinema release, and in the years that followed, this is a sequence I was able to recall almost shot for shot and musically note for note.

The story revolves around Zeke, Smokey and Jerry, three close friends who work on the assembly line of the Detroit auto plant of the title sequence. I'll briefly pause here to note that Zeke and Smokey are both black and Jerry is white, and for the most part their racial makeup is neither commented on nor relevant. Although realistic to the time and location, however, this was almost unheard of for an American film of the day – on the extras on this very disc, Schrader recalls that an early response from a dumbfounded money man was, "You mean two white and one black, don't you?" All three men have become as fed up with their increasingly ineffective union as they are of the factory management, and all are struggling with financial hardship – Jerry works a second job at nights pumping gas but is still unable to pay for his daughter's dental work, Smokey is in debt to a loan shark, and Zeke is trying to support his family by defrauding the IRS. On a visit to the local union branch, however, Zeke notes that the office safe is poorly protected, and the three men hatch a plan to ease their collective financial woes by robbing it, a move that would simultaneously stick it to the union they no longer believe is fighting their corner.

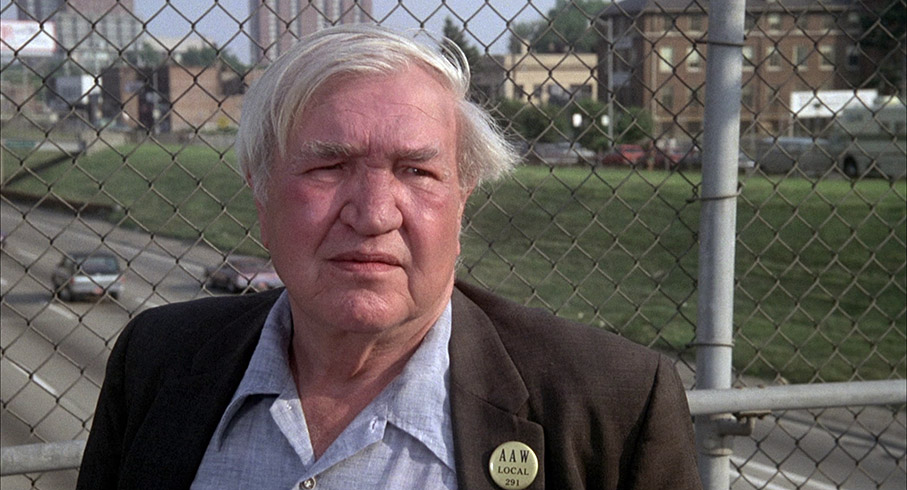

There are so many things that Blue Collar gets right that it's difficult to know where to start. Despite being filmed at the Checker Cab plant after no major car company in America or Canada would allow the filmmakers to shoot in their factory, this is as grittily and convincingly real a portrait of a production line as I've seen in a film – you can almost smell the grease and feel the heat from the welding, and the extras all look as though they've been working at the plant for years. Schrader also gives us plenty of time to get to know the three leads before the plot really kicks off – for the first 40 minutes the film plays as a character drama, painting a compelling if sobering picture of life for those on America's working breadline, trapped in a job that barely pays enough to put food on the table but without which they and their families would go under. That the men are contemptuous of their workplace union steward Clarence Hill is quickly established, but it's also made clear that all three once held the union in high regard and still defiantly defend it when an undercover FBI investigator tries pressing them for information. And when the hot-headed Zeke has a bust-up with bullish foreman, the colourfully nicknamed "Dogshit" Miller, it's ultimately union steward Hill who brokers a peace that allows Zeke not only to keep his job, but also feel as if he's somehow come out of it on top.

This initial focus on character over plot ensures that even when the idea of robbing the union safe occurs to Zeke, we've still got a handful of character scenes to enjoy before all three get on board with the plan, and the robbery itself is as ineptly planned and clumsily executed as it probably would be if carried out by the three men in question. It's also here that most of the film's precious few lighter moments occur, from the semi-surrealistic peculiarity of their chosen disguises to the guard's bemused response when asked to describe the white member of this ramshackle raiding party. It's after this that the story takes a more sinister turn, one I'm not about to reveal here but which delivers some of the film's most memorable sequences, including a claustrophobically horrifying death scene that haunted me for years after I first shuddered my way through it.

Crucially, we really believe in these three not just as working men but as long-standing friends, a minor miracle given that the actors playing them were apparently in constant conflict with each other and their director. Harvey Keitel and Yaphet Kotto are perfectly cast and completely convincing as working-class everymen Jerry and Smokey, both having the physicality, world-weariness and earthy humour of lifelong manual labourers, something Kotto carried over to his next role as engineer Parker in Ridley Scott's Alien. Kotto's imposing physical presence is also put to impressive use, notably in the scene in which he intercepts a couple of company stooges and beats them for information. When I first watched this sequence, the moment when the camera drifts from the two goons over to Smokey waiting patiently in the dark with a baseball bat, I think I actually let out a whoop of excitement at the justice I realised was about to be meted out. The real revelation, however, is Richard Pryor, whose fame as a comedian was at close to its peak in 1978 but who absolutely holds his own against his more experienced companions as the volatile Zeke, particularly in the quieter moments when he reins his anger in and his thoughts and emotions can be seen bubbling away just beneath the surface.

Schrader would later claim that Blue Collar was not a political film, but I can't see anyone who's actually seen it buying into that. Every aspect of the story has a socio-political element, from foreman Miller's use of casual racism as a tool of control to the breadline wages that keep the auto workers in a job that is spiritually crushing them and the suggestion that the union has close ties to both to the local police and to organised crime. It all builds to a sobering conclusion and a memorable final shot in which the capitalistic strategy outlined in the quote at the top is shown to be bearing destructive fruit. It's a bold if downbeat ending to a riveting directorial debut feature from one of American cinema's most distinctive and talented screenwriters, and a film whose relevance and emotional and political punch has not been dulled one iota by the passing of time.

I‘ve said this before, but Blue Collar is one of those films from the 1970s that I remember in part for the gritty realism of its visuals, and I thus came to this new Blu-ray from Indicator with the expectation that the image would not be pin-sharp, that the colours would be dulled and that the grain would be coarse and very visible. Certainly, the intermittently muddy transfer on the 2000 American DVD from Anchor Bay did little to contradict this cloudy memory-triggered assumption. It's thus safe to say that I was bowled over by 1080p 1.85:1 image Indicator's disc, which boasts attractively naturalistic colour and well-balanced contrast, which nails the black levels whilst keeping the essential detail clear even in the darker scenes. And when it comes to the sharpness and picture detail, this new transfer blows the one on Anchor Bay's DVD completely out of the water. The one downside of this is that it's now easy to see that one over-the-shoulder exterior shots of Harvey Keitel in the later scenes is actually out of focus, a victim, no doubt, of Schrader having to work round the volatility of actors who he knew might (and occasionally did) walk at any minute and would likely have refused point blank to do a reshoot. The image is also clean and free of damage. This is how the film should look.

The Linear PCM 1.0 mono track is also in great shape, which is particularly evident in the punchy reproduction of the opening title music and the clarity of the dialogue, even when battling against the noise of production line hammering and whirring.

Subtitles for the deaf and hearing impaired have also been included.

Audio Commentary with Paul Schrader and Maitland McDonagh

This has been ported over from Anchor Bay's DVD and is a seriously good grab. Schrader here provides a wealth of information on the background to and shooting of specific scenes, and film journalist Maitland McDonagh is on hand to prompt him with pertinent questions and pass comment on the film when he pauses for more than a few seconds. There's a lot covered here, including the origins of the project, the casting of the leads, the locations, the supporting cast, the conflict that developed between the principal actors, the title song and Jack Nitzsche's experiments with new music technology. We get some specifics of the consequences of the actors' animosity towards each other and how it influenced the manner in which the film was shot (static master shots were filmed first in case one of the actors walked), and we even get a breakdown of how this rivalry saw the filming of one sequence descend into an all-out brawl. Schrader also admits to being embarrassed by some elements that he believes have dated badly because they reinforce racial stereotypes, and intriguingly describes Pryor as "the unhappiest man I ever met in my life." There's so much more. An essential companion to the film.

Paul Schrader BFI Masterclass

An edited audio recording of a BFI masterclass delivered by Schrader in 1982 that runs under the film as a second commentary track and is only 7 minutes shy of being the exact same length. The masterclass itself is essentially a breakdown of the content and structure of the 10-week classes on screenwriting that Schrader teaches at universities, which frankly sound fascinating – seriously, you can learn a lot about Schrader's approach to his craft from this overview alone. Even his process of selecting candidates for the course is intriguing, as is his assertion that he's less interested in a potential student's talent than in who they are as people. I particularly liked his breakdown of the metaphor that drives The Exorcist, which he neatly summarises as, "you get God and the Devil in a room together to discuss the fate of a little girl." The second half consists of a Q&A session with the audience – the questions are sometimes hard to make out, but are usually clarified by the answers, which, as expected, are always worth hearing.

Visions: Paul Schrader Interview

This first episode of an arts programme from the early days of Channel 4 consisted of an interview with Paul Schrader, who was in the UK to deliver the BFI Masterclass detailed above. Impressively, there are two version of the interview included here.

Broadcast Version with Original Tony Rayns Introduction (20:40)

This is the interview as broadcast, complete with opening titles. It's conducted by Tony Rayns, a now highly respected and widely interviewed authority on Asian cinema, who here is making what I'm guessing from the slightly stiff delivery of his introduction was his first on-camera appearance. Schrader himself delivers the hoped-for goods, discussing his move from scriptwriting to direction, how a seemingly commercial project like Cat People became a personal one, and talking at some length about the changing nature of distribution and how pay-per-view television potentially represents a new funding approach for film production.

Full Interview with New Tony Rayns Introduction (57:39)

Here you can watch the unedited version of the Visions interview, which is fronted by a new introduction from a far more relaxed and easy-going Tony Rayns, who provides a detailed overview of how the series came to be and how Schrader became its first interviewee. Obviously, all of the footage used in Visions is included, but here we get an extra half-hour of interview material and there's some really worthwhile stuff here. Areas of interest include: detail on Schrader's "church state" upbringing; his brother Leonard's move to Japan as a missionary to avoid the Vietnam draft and subsequent loss of faith; how he came to direct his script for American Gigolo and original leading man John Travolta dropped out and was replaced by Richard Gere; why there was a 2-year gap between American Gigolo and Cat People; his work on the script for Raging Bull, and plenty more.

Keith Gordon on Blue Collar (12:11)

Actor turned director Keith Gordon delivers a well-argued and infectiously enthusiastic appraisal of a film he regards as the best and most important American political film of the past 50 years and one of the best-ever great debut features. He cannily deconstructs the film's politics, praises Jack Nitzsche's title song as one of the greatest ever pieces of movie music, salutes the work of the lead actors, and suggests the only thing wrong with the film is that no-one has seen it. In an introduction that warmed my heart, he reveals that he was fired up to do this interview in part because he's such a fan of the work that Indicator is doing. Aren't we all.

Theatrical Trailer (2:35)

I may be wrong here, but this looks suspiciously like a rebuild of the original trailer using clips from this remastered print of the film, a view evidenced but the HD digital crispness of the textual graphics. There are plenty of spoilers here, and the memorable final shot is included, so don't watch this before seeing the film itself for the first time.

Josh Olson Trailer Commentary (2:52)

Screenwriter Josh Olson provides a Trailers from Hell commentary, in which he briefly covers elements of the film that he admires, and expresses his belief that social and political issues are best handled by genre films.

Image Gallery

37 slides of production stills and posters, all in crisp HD.

Also included is a Booklet containing a new essay by Martyn Conterio, an overview of contemporary critical responses, and historic articles on the film, but I've not seen this yet. I'll update this review when I get my hands on a copy.

I was genuinely thrilled when Indicator announced that they would be releasing Blue Collar on Blu-ray. It's a film I fell in love with when I first saw it on its initial UK cinema release and that I have been championing ever since to people who've never even heard of it, let alone seen it. Well, now's your chance, as this is the Blu-ray release that the film deserves, boasting a lovely transfer and a terrific set of extras. It's everything I hoped it would be. Highly recommended.

|