|

It probably won't surprise you that much to learn that when I was at film school, just about everyone there was director-focussed. Each student had their list of favourite feature filmmakers, and being the late 70s, there were plenty of contemporary names to add to the ones whose work we were retrospectively discovering through film theory classes, late night TV screenings and the local arts cinema. At this point, we had yet to focus on the considerable contribution made by screenwriters, but most of my classmates had already made note of one name, and purely on the basis of one particular film. The film in question was Taxi Driver, a title with which the (male) film students of the day were as obsessed with as the next generation came to be with Reservoir Dogs. As a piece of filmmaking it was revelatory and Robert De Niro's central performance just blew us away, but we were also very aware of the role played by Paul Schrader's extraordinary screenplay, from which we were endlessly quoting. From that point on, not only did we seek out anything directed by Martin Scorsese, but also anything penned by Paul Schrader. And while the pickings were limited at this point in the careers of both men, they were seriously rich. We were able to track down Scorsese's Mean Streets and Alice Doesn't Live Here Anymore thanks to reruns at the local arts cinema, and a few trips to London exposed me to the pleasures of Schrader's scripts for The Yakuza, Obsession and Rolling Thunder. As you can imagine, the news that Schrader had moved into the director's chair generated considerable excitement, and for me Blue Collar, a riveting and thematically complex thriller of workplace corruption and working class betrayal, definitely lived up to expectations.

It was a couple of years before I caught up with Schrader's second film as writer-director, which was released in the UK under the preposterous retitle of The Hardcore Life, presumably because of the pornographic implications of the don't-fuck-about actual title, Hardcore. Pornography certainly plays a key role here, but the film itself is in no way pornographic or even cheaply titillating. This is, after all, a Paul Schrader film, something fans of Taxi Driver should have no trouble picking up on as the story unfolds. And there are further elements of interest here for those who know a little bit about this filmmaker's background.

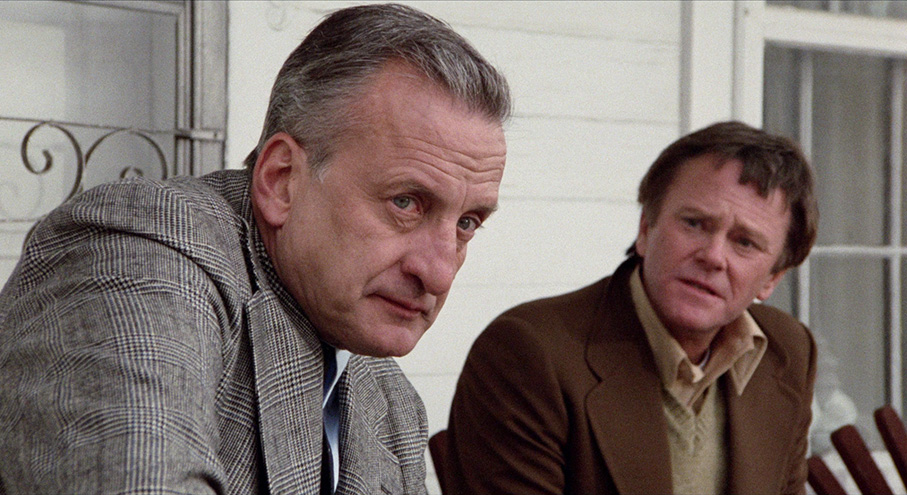

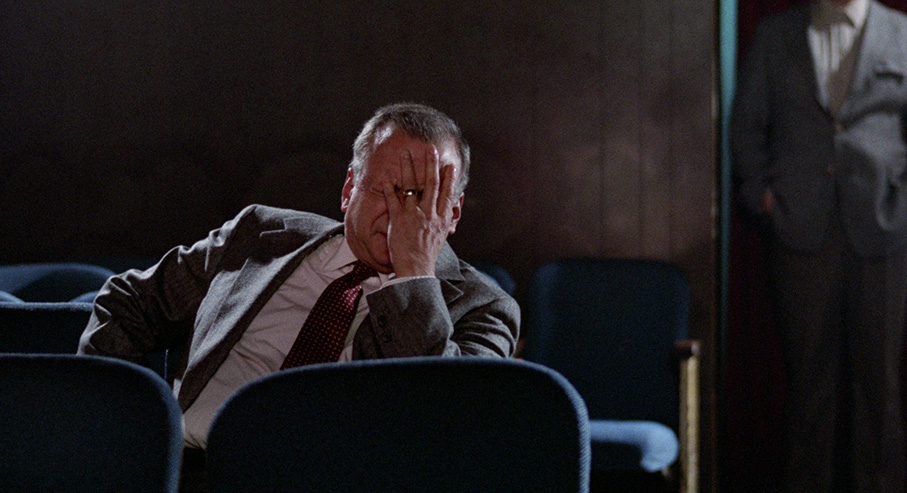

Jake VanDorn (George C. Scott) is a single father and a devout Calvinist businessman whose daughter Kristin (Ilah Davis) disappears whilst on a church trip to Los Angeles. The police aren't much help, so Jake hires private detective Andy Mast (Peter Boyle), who discovers that Kristin has appeared in a hardcore pornographic film. Presumably under the belief that a man of Jake's religious conviction would refuse to believe that his daughter would take part in such a disgusting enterprise, Mast sits him down in an empty cinema and shows him the film, which prompts Jake to break down in despair. It's a key scene for the film and for George C. Scott as an actor, as his initial discomfort gives way to a furious and physically agitated horror that he comes perilously close to overplaying, but that he brings back to earth with the convincingly tearful outpouring of grief that follows. If I seem to be spending a disproportionate amount of time on this single scene, it's because there's a chance that even those who've never heard of Hardcore may well have seen it in a re-edited form. Like Bruno Ganz's angry rant as Adolf Hitler in Downfall, which has been re-subtitled to have him rail against everything from an outage on Twitter to the reckless selling of sub-prime mortgages, this sequence has become the basis for an internet meme, one in which Scott reacts with increasing horror to the trailer for the woeful Adam Sandler comedy, Jack and Jill.

But I digress. The hunt for Kristin continues, but when Jake catches Mast making out with one of the porn stars, he angrily dismisses him and starts his own investigation, which takes into a world that he finds morally repugnant. Posing as a backer for a new pornographic film, he meets and hires young porn actress and prostitute Niki (Season Hubley) with the intention of using her knowledge of the adult film industry and its players to help him find out what has become of his daughter.

For those who know Taxi Driver, some of this should have a familiar ring, as both films feature a morally uptight adult male protagonist who befriends a young prostitute, one whose liberal attitude to sexual matters directly contrasts with that of their morally conservative companions. The connection is further cemented here by the presence of actor Peter Boyle, cinematographer Michael Chapman, editor Tom Rolf and music editor Shinichi Yamakazi, all of whom also worked on Scorsese's film. Yet while Travis in Taxi Driver is driven by barely suppressed (self-) righteous rage, Jake's quest is fuelled largely by desperation and anguish, and where Travis's anger is an unfocussed extension of loneliness and prejudice, Jake's explosions of fury are deeply personal in nature, as he descends into a world from which he has been previously shielded by the ethical cocoon of his religious convictions. There's also more than a whiff of The Searchers about the journey he undertakes, a connection underlined when Mast warns him after the traumatic film screening, "Look, I'll find her, but I can't make any promises. I don't know what she'll be like when I find her. And when I find her, you may not even want her back."

Jake's religion plays a key role in his quest and his attempts to comprehend the business into which he must bluff his way, and in the respect Hardcore is probably Schrader's most personal film. Like Jake, Schrader came from a strict Calvinist background and here reflects on the teachings and moral constraints of the religion through Jake's investigation, his home life and his conversations with others. This is at its most blatant when Jake explains the meaning of the acronym TULIP* to a curious and questioning Niki, which although a logical exchange in terms of their working relationship, does feel primarily designed as exposition for an audience unfamiliar with the finer points of the Calvinist religion – I certainly was when I first saw the film.

The danger, at least for a first-time viewer, in making Taxi Driver comparisons is that it risks creating expectations that Jake's journey will follow a similarly explosive path, and that his building disgust and anger will ultimately be unleashed through the barrel of a .44 Magnum, a presumption given abstract weight by the foreboding strains of Jack Nitzche's wonderfully discomforting score. But Travis and Jake are very different individuals, and while Jake may be held morally captive by the teachings of his church, he is an otherwise stable individual who cares deeply for his family and friends, and has none of Travis's isolation-fuelled psychopathy. Both men ultimately take confrontational action that is triggered by their individual definitions of righteous anger, but while we're left with the sense that Travis will remain a potentially lethal coiled spring of rage that will one day explode, there's a sense that although Jake is traumatised by his experience, he will somehow find a way to live with what he has been through and return to an albeit redefined concept of normality.

Where Hardcore does share common ground with Taxi Driver is in its ability to bond us to a judgemental central character and force us to view the world through his eyes, however his views may differ from our own. And as with Taxi Driver, much of this is down to the lead performance, with George C. Scott delivering a masterclass in supressed (or should that be repressed?) disgust and despair, while his occasional explosions of righteous fury are frightening in their conviction – this is a man you really can imagine standing on a pulpit and scaring a congregation into unquestioning belief through terrifying tales of what the fires of hell will hold for the non-devout. Intriguing, then, that Scott and Schrader apparently had a frosty relationship during the shoot, and word has it that Scott even made Schrader promise never to direct another feature, an assurance I'm assuming he gave with his fingers crossed firmly behind his back.

I'm not sure whether Hardcore can be classed an underrated Schrader work when so few seem to have caught it since its initial release – a quick poll of friends found that none of them had seen it and only one was even aware of its existence. Certainly, as a film drama it still stands up well. Schrader's screenplay is thoughtful, well-constructed and just occasionally rather witty (one memorable remark about a talented young porn director having graduated from the University of Southern California – whose many distinguished alumni include John Carpenter, Ron Howard, George Lucas, John Milius and Robert Zemekis – just has to be an in-joke that this member of the audience is not in on) and his direction restrained, with none of the arresting visual flourishes of his next film, American Gigolo or his 1985 masterpiece, Mishima: A Life in Four Chapters. Maybe it's the lingering trace of Schrader's own Calvinism, but I would argue that the film never confronts the world in which it is primarily set with the sort of unblinking frankness that the story, subject matter and even title demand, something not helped by the passing of time and a notable handful of subsequent films that have gone further on this score. Yet Hardcore remains a consistently gripping blend of social drama and character study, one whose journey into the sleazy underbelly of American society may not be as incendiary as in Taxi Driver or as riddled with despair and paranoia as Schrader and Scorsese's Bringing Out the Dead, but still proves to an appropriately dark and discomforting ride.

The Blu-ray in this dual format set boasts a very strong 1080p HD transfer from a 4K restoration by Sony from the original negative. The contrast is spot-on, the black levels crisp, and the shadow detail is good even in darker scenes (Michael Chapman really knows how to shoot clear night exteriors). The colour is very robust and lively when required (the neon lights on shop fronts, the red and blue bathed peep-show club interior), and the image detail is consistently crisp. The picture is spotless, with no dust or damage, and a fine film grain is visible throughout. A very strong transfer.

The remastered Linear PCM 1.0 mono soundtrack is also in great shape, with clear rendition of the dialogue, and great-sounding music. There is a very slight treble bias to the dialogue that is typical of mono soundtracks from this period, but no trace of background hiss or damage.

Optional English subtitles for the deaf and hearing impaired are also available.

The Guardian Interview with Paul Schrader (94:42)

One of those sonically imperfect but still priceless interviews with filmmakers conducted at the National Film Theatre in London that are now starting to crop up as special features on dual format releases by our favourite distributors, this, in my humble opinion, is one of the best yet. Hosted by critic Derek Malcolm and recorded in 1993, the interview finds Schrader in lively form (I've seen enough interviews to know that this isn't always the case), covering a lot of ground in response to questions from Malcolm and the audience, though I don't think Hardcore even gets a mention. Pleasingly for us Mishima fans, however, there's quite a bit on that film, including how the project came to be, the opposition to it from Mishima's widow, and Philip Glass's extraordinary score. There's lots more here on a variety of films and subject areas, and the interview as a whole is a terrific listen. Pleasingly, it plays under the film as an alternative soundtrack, sparing us plasma TV owners from screen burn.

Shooting Hardcore (9:06)

In the third extract from this Web of Stories interview with director of photography Michael Chapman to feature as an extra on an Indicator disc (the others were on The Front and The Last Detail), Chapman recalls his experience shooting Hardcore. It's a film he is unable to look back on objectively, in part due to the decision to shoot in real porn industry locations, an experience he winces at the memory of (in one telling moment, he wrinkles his nose in disgust and says, "the smell..."), but also because he originally envisaged shooting the film handheld on 16mm in a faux documentary style, a plan that was ditched once George C. Scott signed on for the lead role. He does have one positive memory of a technical aspect, which should prove interesting for all budding camera people out there.

Hardcore Nitzche (22:25)

Announced up front as an edited excerpt from an upcoming feature documentary titled Stringman (about which I'd like to know more), here a number of filmmakers and musicians recall working with composer Jack Nitzche and celebrate his work. I say celebrate because the general consensus here is that Nitzche was a hugely talented and inventively experimental musician (you'll get no argument here), a view encapsulated by fellow musician Tony Berg, who says of Nitzche's astonishing work on One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest. "Fuck me, that was just a profoundly beautiful score." It begins, however, with a number of the contributors listening to some of what we can assume are some of Nitzche's more extreme creations, which at one point cause musician Ron Nagle to shake his head and pull off the headphones, bury his head in his hand and cry out "Oh my God..." and the great Ry Cooder (whose uncredited work can be heard on the soundtracks of both Performance and Hardcore) to contort into an expression of genuine horror. It's an excellent extra, and the final roll-call of films that Nitzche scored serves to remind you just how significant his contribution to film soundtracks was.

Isolated Score

Not an ideal way to listen to the score due to the lengthy silent stretches between the bursts of music, but as far as I'm aware not soundtrack album was ever released, so this will have to do. And the music is so damned good...

Theatrical Trailer (1:21)

"Nothing you have ever done, seen or imagined can prepare you for the experience of Hardcore" is the presumptuous claim made by a trailer that tries to trade on a shock value the film never had, but does put Jack Nitzche's score to rather good use.

Image Gallery

21 slides of behind-the-scenes photos and promotional material, which are manually advanced.

Booklet

Another typically well-produced booklet from Indicator, this one kicks off with a perceptive essay on the film by Brad Stevens, which is followed by an extensive interview with Schrader about the film, originally published in Focus on Film in August 1979 and conducted a few days before the start of principal photography. This is especially welcome, given that Indicator have clearly been unable to licence the Schrader commentary from the American Twilight Time release, which also includes a commentary by film historians Eddy Friedfeld, Lee Pfeiffer, and Paul Scrabo. Credits for the film and brief details of the restoration have also been included.

Not as shocking or even disturbing as some contemporary reviews once claimed, or as cinematically distinctive as the three Schrader films that followed, Hardcore is nonetheless an intelligently scripted, convincingly acted and consistently involving early work from one of America's most intriguing and talented writer-directors. A shame we couldn't have the Schrader commentary, but in all other respects this is another serious thumbs-up for Indicator. Recommended.

|