| Eddie Jessup: |

What's whacko about it, Mason? I'm a man in search of his true self. How archetypically American can you get? Everybody's looking for their true selves. We're all trying to fulfil ourselves, understand ourselves, get in touch with ourselves, face the reality of ourselves, explore ourselves, expand ourselves. Ever since we dispensed with God we've got nothing but ourselves to explain this meaningless horror of life. |

| Mason Parrish: |

You're a wacko. |

| Eddie Jessup: |

Well, l think that that true self, that original self, that first self, is a real, mensurate, quantifiable thing, tangible and incarnate, and I'm going to find the fucker. |

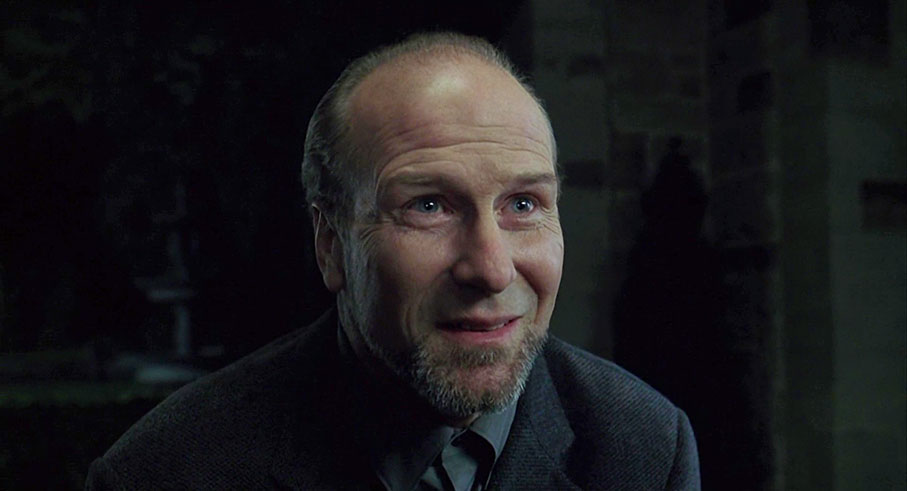

With that one exchange from Altered States, William Hurt settled comfortably in to my own mind’s ‘Cinem-attic’ where I store interesting and potentially intriguing films, shots or performances. Here was a character actor both blessed and cursed with a film star’s looks and build who was headlining a Ken Russell film in his movie debut. The power coming off this man, in this startling performance of an obsessed scientist trying to solve a mystery of the ages, was mesmerising. Teamed up with a brilliant supporting cast including the sympathetic Bob Balaban and the adversarial Charles Haid not to mention the superb Blair Brown who plays his wife, Hurt took what could have been a psychotic outsider into the realms of the fantastic, surreal and oddly credible. I fell hard for this character, the film and its innovative score and was somewhat obsessed by the make-up effects by Dick Smith. But the great William Hurt has died and if nothing else, his passing has highlighted his work and made me appreciate his incredible performances even more.

At the start of his flirtation with movie stardom, he had the reputation of being somewhat pretentious. A director friend of mine said that actors like Hurt should be dropped on their heads after hearing a quote from the actor (and I cannot find it online) saying something very close to “I’d like to die being whipped into instantaneous ether…” Of course we never know the context of this bit of silliness but if nothing else, that sort of quotation does stay in the mind. Hurt’s earlier work stands out for me with one overlooked film that really needs some rediscovery. From director Peter Yates and screenwriter Steve Tesich (the pair responsible for the sublime Breaking Away) came a film originally called The Janitor and then was wisely changed to something a little more compelling, namely Eyewitness. I remember getting a call from a good friend who was stunned by Hurt’s work in this film, so much so that he got me to jump on my bike and cycle for an hour to share it with him. I remember him saying that there was no actor in the role. He was the character and was so convincing, there was never any sense that you were watching a performance. For his next part, he played the womanising lawyer Ned Racine who enters into a pact to murder his new lover’s husband. Body Heat paired Hurt and Kathleen Turner as the scheming murderous pair. It struck me that early in his career, Hurt was unafraid of playing unsympathetic parts. He was the patsy here, an inept lawyer, a man driven by his sexual conquests to whom Turner memorably said “You’re not too smart, are you? I like that in a man.” There’s only one moment in the film where Hurt’s character truly surprises Turner’s as for most of the film he’s completely in her thrall… It’s their first meeting on a stultifying hot Florida evening. The dialogue is Hollywood whip smart (I’m pretty sure real people do not speak like this) but Turner asks Hurt “How does Pinehaven look?” (an expensive place to live she’s been compared to). “Well tended.” Replies Hurt. He then goes on to say he needs tending, someone “…to rub my tired muscles, smooth out my sheets.” She whips back with “Get married.” Hurt looks askance and delivers the knockout blow, “I just need it for tonight,” at which Turner spits out her fruit ice in shock.

So is it any surprise that Hurt’s next movie, The Big Chill, he played a man with no sexual function at all? Nick had his bits blown off in Vietnam. To those who focus on Hurt’s serious demeanour, you should see how silly and warm he could be in this terrific film of lost dreams and the celebration of friendship. I can’t wash up now without the lyric “I know you wanna leave me, but I refuse to let you go…” popping up toast-like in my mind. Hurt’s general presentation, his default physicality and aspect is that of a man lost. He had a haunted look that could suggest great depth. He also knew the immense value of stillness on screen. He earned his Oscar in the flamboyant role of Luis Molina, an effeminate gay man imprisoned for raping an underage boy in Héctor Babenco’s Kiss of the Spider Woman. Again, Hurt commands the screen playing another initially unsympathetic character whose love for his cell mate, political prisoner Valentin played by Raul Juliá, develops over time. Hurt rebelled against Hollywood’s expectations of him and he earned his living co-starring in independent productions tip-toeing back into full scale blockbuster territory by joining the Marvel Cinematic Universe re-playing his General Ross first seen in Ang Lee’s The Hulk (2003). But for my money, his best most recent performance was in the extraordinary History of Violence directed by David Cronenberg.

His small role as Viggo Mortensen’s criminal brother Richie presiding over his brother’s botched execution is a masterclass of character acting. Again, Hurt is able to divest himself of himself. It’s clearly Hurt in the role but the character is somehow shifted from himself in a way that is riveting to watch. The vocal inflections and delivery are as far from Hurt as you can imagine but he ‘is’ Richie, cold, vicious, ambitious, long suffering and commanding. Richie responds to his brother’s plea to make peace. “You could do something I guess. You could die, Joey…” before turning around in his swivel chair reminding me completely inappropriately of The Mighty Boosh’s Naboo as he temporarily ostracises Vince. Behind him Joey is being throttled with a cheese wire. Within seconds Joey gains the upper hand. Richie takes out a gun and stares in utter bafflement as Joey lays waste to his three henchmen. Joey escapes as Richie approaches his dying men. Exasperated he softly says, leaning over the bested cheese wire guy, “How do you fuck that up?” and then, as rage takes hold, a louder delivery of the same line followed by a shot to the stricken man’s heart. Hurt is absolutely enthralling in this scene and I will always wonder how George Clooney pipped him to that particular Oscar post for his turn in Syriana.

William Hurt died of ‘natural causes’ after a terminal diagnosis of prostate cancer which was revealed in 2018. He was an actor who brought a great deal to the craft, demanded rehearsal time and researched his parts with gusto. I leave you with a fellow actor’s sign off, tweeted shortly after his death. Russell Crowe said:

“William Hurt has passed. On Robin Hood, I was aware of his reputation for asking character based questions, so I had compiled a file on the life of William Marshall. He sought me out when he arrived on set. I handed him the stack. Not sure if I’ve ever seen a bigger smile. RIP.”

As memorial notices tend to focus on the good work of the recently deceased, it’s sobering to understand that Hurt had his significant demons which he did acknowledge in his lifetime. In Marlee Matlin’s book I’ll Scream Later, (she and Hurt hooked up after starring in Children of a Lesser God together) she writes about several horrific incidents of Hurt’s mistreatment towards her, both psychological and sexual abuse. These stories are hard to refute. And I don’t want to sweep them under the rug. That said, all I saw and knew of Hurt was his work. I hope that’s still possible to appreciate. RIP, William Hurt.

|