"As the supernatural events occurred you searched for an explanation,

and the most likely one seemed to be that the strange things that were

happening would finally be explained as the products of Jack's imagination.

It's not until Grady, the ghost of the former caretaker who axed to death

his family, slides open the bolt of the larder door, allowing Jack to escape,

that you are left with no other explanation but the supernatural." |

Director Stanley Kubrick nailing his paranormal colours

to the mast in conversation with Michel Ciment |

Did you see The Innocents, Jack Clayton's wonderful take on Henry James' Turn of the Screw? In the movie, a blob of water could be seen as evidence that the ghosts can conceivably be interpreted as 'real', a piece of the puzzle the director later regretted including. This scuppers my reading of the film, one that supposes that everything was in the tortured mind of the governess and that she was the grotesque, sexually repressed villain of the piece. I'm now imagining a new scene in which Deborah Kerr carefully places a blob of water on the table while under the influence of her own psychosis. Naughty. My huge problem with The Shining on my first exposure to it was precisely what Kubrick seems to be underlining here. The supernatural stuff is supposed to be real and not the fantasy of a rapidly crumbling adult mind driven mad by obsessions and paranoia and the horrific visions of the past generated by a child with a singular mental gift. How, I wonder, can I effortlessly accept Guillermo Del Toro's ghostly child in The Devil's Backbone and not cut Kubrick any slack? In the relevant scene of Jack Torrance locked inside a store cupboard, you get the ghost Grady's voice and Jack's smile with only the unbolting sound effect to 'prove' the supernatural is real and can physically affect the 'real' world. This was simply not enough for me at all. It's obvious in all other cases that the 'ghosts' and visions are in Jack's head. This, as you can see, is my problem, not Kubrick's. And so, it's time to re-examine my response to a movie that should not have given me so many misgivings.

Very few movies garner such widespread critical opprobrium at the time of their release and then over the years manage to pry loose the stubborn barnacles of disapproval. They emerge as not only previously misjudged but significant works to be re-evaluated and pedestalled as pieces of art generating multiple passes of meaning and intent. If directors are ahead of their time (a phrase I still find hard to grapple with meaning-wise) then judgement of their work by those passing such opinions will never be relevant if there is such a thing as relevancy in film criticism. In his long career (but alas directing only a relatively short number of movies), Stanley Kubrick flustered critics by encouraging his work to be interpreted and re-interpreted. It seemed to be his modus operandi. This is certainly true for the director's masterpiece, 2001: A Space Odyssey, a movie that generated U-turns by many critics of repute. But it's his 1980 Stephen King adaptation, The Shining, which seems to have not only shrugged off its initial reputation but now stands tall as a masterpiece of modern horror, finally living up to the tagline of hype that proclaimed its credentials on the yellow, stark, weird-child poster of its release. I'm not supporting either polarised claim (it can be both something of a disappointment and a masterpiece whichever way you choose to look at it). I'm more interested in how this movie managed to produce so many interpretations and why so many of those hold about as much water as a one-hole colander. After a few viewings of the movie's documentary front and centring five distinct readings of the film (Room 237) and having recently read Roger Luckhurst's BFI Classic on the film, I thought I'd apply some practical filmmaking sense to some of these straw-clutching re-readings.

If you've not seen the 1980 'horror' film (and yes, I've placed 'horror' in inverted commas for a reason) then a swift synopsis would be a good start. Be aware that this is a snapshot of the skeleton of the plot. There is a lot more going on in this movie (or so it's been suggested) than is apparent from the following. Jack, his wife Wendy and son Danny take up a caretaking job in a large, open and somewhat spooky hotel which closes down for the winter. Lots of horrific things have happened here.

Danny, who has a telepathic gift christened 'the shining' by the similarly gifted head chef, starts to have a series of disturbing hallucinations (or visions of the 'real' supernatural). As they become more frequent, his father Jack starts to unravel and begins to interact with the ghosts of the hotel, one of whom, Grady, offed his whole family with an axe, an act Jack seems destined to repeat as he finally cracks and hunts his family down. Sounds pretty normal as the premise for a horror movie? A guy goes nutso with an axe? All is in place albeit a little on the nose for a Kubrick movie. The novel (a great deal of which Kubrick discarded) is an astonishing read. I remember serving at a wine shop while I was reading it and politely asking customers to come back so I could at least get to the end of a chapter. There were scenes in this book I knew Kubrick would knock out of the park. There's one moment in particular that I couldn't wait to see on screen, the moment Danny reveals the full force of his gift to the chef. It makes the man's hair stand on end in shock. Kubrick cast a bald man as Halorann – Ah. OK. I was sure there would be more moments. It's worth mentioning that the European version of the film had over twenty-five minutes excised. I'm going to be discussing the American long version. Both can be read in similar ways although the difference between them changes the context of certain psychological aspects and their importance to the overall emotional effect. I do wonder why Kubrick pared his own movie down. I'm not sure if I buy the obvious reason for this drastic step (I imagine it was to make the film 'more commercial' whatever that means) and with respect to my American friends but it's usually Europeans who get to see the 'artier' version which in this case has to be the longer one. There are many mysteries here and there are enough to be going on with in the actual film itself. It burns me that I do not have access to The Stanley Kubrick Archive, that massive tome with much previously unpublished material inside. Damn this house moving box-life.

"There ain't nuthin' in Room 237..." |

Hallorann played by Scatman Crothers

(and we're going to forgive the double negative) |

Even if we believe Hallorann – which Danny should if they both have the telepathic ability known as 'the shining', a searingly honest conduit from one mind to another – it's simply not true. Not only is Room 237 absolutely crammed with meaning, symbolism and Freudian allusions, the whole movie seems to be an academic's wet dream. Stanley Kubrick, like no other filmmaker, pored over the minutiae, hovered divinely over the detail and settled for no less than a perfect celluloid rendition of the ideas coaxed from his imagination. In a formal interview, Nicholson said of his director "...he gives a new meaning to the word meticulous." Some ideas took months to coalesce but there seems to be little doubt that if you can see something in a Kubrick movie, it was either Kubrick's direction that placed it there or Kubrick's acceptance of what was suggested by the art department that places it in front of the lens. So, the corollary of this attention to the finer elements of his mise-en-scene is that everything was intentional. Really? This is how it should be in Perfectville but in the hurricane of production, often control is wrested from even the most meticulous of directors and frankly things screw up, other things suggest themselves and even film directors like Stanley Kubrick become victims of the movie gods. Remember Raiders of the Lost Ark's biggest audience reaction was because Harrison Ford had the squits...

It doesn't matter how good you are, how much you spend and how long you take to make a movie, mistakes are part of any movie's DNA and only by smoothing out errors with CG in post production can these be expunged from the finished work. CG was on the cusp of maturity in 1999 – the year Kubrick died – so his own mistakes are still trapped in the celluloid. There are some people who impose meaning on these mistakes (as they have every right to) and I also have the right to underline those mistakes as mistakes. I have been making films for over thirty years and I know a meaningless, basic continuity error when I see one.

Allow me a ridiculous but pertinent digression. In the 80s US comedy Cheers, waitress Diane (Shelley Long) is being wooed away from bar owner Sam (Ted Danson) by an eccentric artist played by Christopher Lloyd. Sam is desperate. He knows that Diane is a sucker for intelligence and artistry (two things he's certain he does not possess). In retaliation, he arranges for his own portrait of Diane to be painted based on a photograph. He shows this portrait to his friends at the bar. They ridicule the painting, not unfairly as it's ridiculously simplistic and childlike, and Sam (obviously thinking that there was nothing wrong with the picture) immediately pretends the portrait was commissioned as a sort of ironic joke ("I knew that!") even though that kind of thinking may be beyond Sam too. As Diane arrives with the real portrait, the relationship descends into superbly performed physical farce. Sam's ego will not let him even look at Diane's painting. Diane's frustration with a less than tolerant boyfriend reaches a semi-violent climax with much slapping. The scene ends with Diane leaving and Sam is left with the painting. He tears the brown wrapping off. He looks at it. He simply says "Wow!"

The Two Dianes...

It's a stunning end to a season and a relationship. If you're still with me, Kubrick is the artist but most of us (seeing a film for the first time at the very least) will only see Sam's childish portrait. We can laugh at it, dismiss it even. I didn't have either of these reactions when I first saw The Shining but I was seriously handicapped by loving the novel (so disappointments were frequent on the road on which I was walking). I found the film dispassionate, removed and more importantly not scary in the least. So it was about time I looked at the other portrait, the 'real' portrait and stayed as open as other people on what Kubrick's intentions may or may not have been. Before I indulge myself with what must be a tenth viewing with sensors on sensitivity level 11, let's take a brief look at what others have been saying...

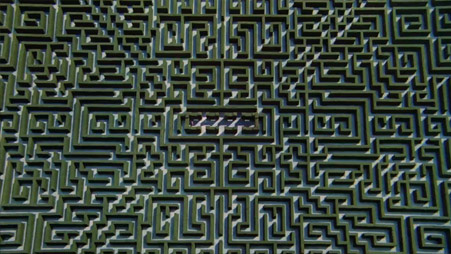

The documentary Room 237 is very entertaining and extremely ridiculous all at the same time. There's a theory (another one!) that it's supposed to be seen as ridiculous. I give up. It seems I got lost in the post-modernism. It's also neatly divided into the inspired and insipid. The latter more wanting of sense theories, if I was being lenient, give a new meaning to the word 'circumstantial' while the former make you wish dear Stanley was still with us so he could confirm or deny. What annoyed me slightly about Room 237 was also its peculiar strength. It gave five people a platform to sell us their ideas about Kubrick's movie but no theory, idea or guess was ever challenged. There were so many occasions where I sat there, slack jawed, saying "But that's just not true!" Let statements, facile ones at best, pass by in a rigorous documentary and you damage your argument. But then the only argument in this love letter to The Shining is "Look how much significance we are attributing to this extraordinary film." All that fuss over the 'Minotaur' in the poster above the twins' heads... It's a skier. It really is a skier. The poster to its right looks more like it could be interpreted as a Minotaur. But the poster on the left? It's a skier. It says 'SKI' and features a skier. But then I thought "What if Kubrick designed it so that we thought it was a Minotaur?" What would be the point of that? There's a maze in the movie and symbolism is rife throughout but what would be the academic or intellectual point of this skier suggesting a Minotaur (which it doesn't). OK, so Kubrick once used 'Minotaur' as a production company name but despite this obvious link, what would be the point except as a sort of in joke and when was the last time Kubrick made an in-joke in one of his movies? That behaviour is for the George Lucases of this world. It's a skier. Even Kubrick's assistant Leon Vitali was as astounded as I was hearing some of these 'theories'... One of the participants talks about the minor character Bill Watson (played by Barry Dennen) and his strange brown skin. He doesn't have strange brown skin. He has normal Caucasian skin with imminent stubble darkening the tone. But so what if he did have brown skin, what would this signify?

Movies are complex beasts and on a Kubrick set where over a hundred takes are not uncommon, scenes can be split over days. Despite Polaroids for continuity's sake, things get forgotten, lost. Much was made of a missing chair in the background of the scene of Wendy encountering a belligerent Jack at his typewriter. Unless the Summarian for 'missing chair' is a homonym in English sounding like "Watch out Wendy, Jack's going bananas..." there is no significance here at all. The mysterious ball that appears as Danny plays with the toy vehicles and the 180 degree cut revealing the carpet's discontinuity... It's a mistake, guys! Even Stanley was prone to them. What occurs to me is that once you are scrabbling for meaning at this, the lowest level of hoped-for significance, anything and everything is up for grabs. You could go through almost any movie and assign meaning and intent onto any scene and any shot. Perhaps this is the comedic point of Room 237... The erect penis theory (surely, Room 237 could not get any sillier or inane? No wait, there is another) as Ullman (Barry Nelson) moves in front of his desk and has a near vertical line of his in-tray appearing to originate from his zipper. Oh, puhlease... But my favourite was a long-winded introduction to an airbrushed painting of Kubrick in the clouds just as his front director's credit disappears off the screen.

See it? Nor do I. Not only is this desperate bullshit, the filmmakers couldn't even isolate what the hell was being talked about with an arrow as they did with the rest of the theories' 'evidence'. This 'theory' was hung out to dry before there was a shred of proof. But again, I ask my question. Why would Kubrick put an airbrushed picture of himself in the sky?

Here's one of my own that was missed. Can't imagine why our five contributors didn't catch this one. In the early scene with Danny in bed and the doctor examining him, there is a Goofy doll on the shelf on the right. Now, I am a fan of Shelley Duvall and believe she had a tough time on this shoot so I don't want to add insult to 35 year old insults but let's forget the physical similarities (prominent teeth and long black hair as 'ears') and concentrate on the clothes which are pretty much identical. But what does this mean? Wendy is Goofy. Wendy (the woman who wends her way) is faced with being stuck in the Goo. And the goo connected to a fee will make her pay for her meandering ways. This is great fun and obviously ridiculous but my Wendy/Goofy theory carries more weight than some of the ideas in Room 237 and that's saying something. On the subject of Duvall, her performance in The Shining will always tend to be overlooked in favour of the quintessential Nicholson performance. But it is an astounding turn from a gifted actress who is playing a relentlessly unsympathetic character. She is never less than utterly convincing and sometimes painfully so. I'm so glad that writer Roger Luckhurst agrees with me.

"I watched the version without the doctor's visit for years, unaware

that there was another scene that doubled Jack's interview in Ullman's

office. This scene's absence doesn't make it a worse film only one with

a different shape and a more enigmatic, more mythical tone." |

Roger Luckhurst, author of the BFI Classic on The Shining |

I was also overly familiar with the shorter version, so much so that I reeled at all the 'new' scenes despite having seen them, perhaps isolated some time in the past. On more solid critical ground is Roger Luckhurst's academic dissection of the movie that is thought provoking, rigorous and entertaining. He goes through scene by scene noting the theories associated with the different readings (he is almost mockingly dismissive of some of Room 237's sillier ideas as he should be) but his own ideas carry enough weight to be intriguing and persuasive. I often felt that Rodney Ascher (director of Room 237) really should have had a chat with Luckhurst before finishing the edit of his own project (unless of course it was meant to be ironic...)

So, thirty-five years later, how does The Shining hold up?

Surprisingly well, to be honest. What really dug deep was the sound design and use of music and marriage of the two. The diverse score had echoes of William's work on Close Encounters and Goldsmith's score for Freud but as Kubrick's source cues were written decades before either named score, I have to acknowledge these giants of movie music may have aped earlier styles and orchestrations. It's quite sobering to accuse A of borrowing from B when you find out that B was born many decades after A. The movie on the whole was unsettling but I remained not scared in the slightest (mostly due to my familiarity though having said that I still jumped at my umpteenth viewing of Halloween, 37 years on). But the performances are extraordinary (you have to remember that this was Nicholson's first formation of the 'Jack Nicholson' persona. Kubrick pushed the actor who was a little nervous to be let so far off the leash). As I said, Duvall was utterly convincing. Danny Lloyd is extremely comfortable as Danny and conveys his unease and terror at his own ability with a skill I have to lay partially at Kubrick's door. Lloyd is a natural but it takes great direction to capture that kind of a performance on screen. The Grady-lets-Jack-out-of-the-storeroom scene still makes me seethe with frustration (if only we'd see him do it and not just hear it...)

Duvall's suddenly coming across cobwebbed skeletons in full evening dress in one of the Overlook hotel's expansive rooms (a cut scene from the European version) seems utterly un-Kubrickian – gothically obvious, almost cheesy. I really do wonder what the thinking was behind that decision. At first I welcomed the inclusion (something else in the movie I may be a little more scared of) but alas, it's just (gasp) ordinary. It's a great testament to a movie if it remains debated and viewed a long time after its release. Kubrick was a unique talent and if anyone's work is worth poring over for hidden and not so hidden meanings then Kubrick's your man. He was also, I must remind you, a man and men and their film crews make mistakes. I'm still not convinced that the movie is "...the most stately, artful horror film ever made," but then again, I don't know what may be; that's a narrow definition. How many horror movies are in the 'stately' category? Here is where that quote came from and I'll end on that with a personal note of puzzlement about what all the fuss is about...

| "Just as the ghostly apparitions of the film's fictional Overlook Hotel would play tricks on the mind of poor Jack Torrance, so too has the passage of time changed the perception of The Shining itself. Many of the same reviewers who lambasted the film for "not being scary" enough back in 1980 now rank it among the most effective horror films ever made, while audiences who hated the film back then now vividly recall being "terrified" by the experience. The Shining has somehow risen from the ashes of its own bad press to redefine itself not only as a seminal work of the genre, but perhaps the most stately, artful horror ever made." |

Horror film critic Peter Bracke reviewing

the Blu-ray release in Hi-Def Digest |

|