|

"Would you like to interview Jan Švankmajer?"

Say what?

We get a lot of PR emails at Cine Outsider. Some we ignore (did anyone seriously think we were going to promote the likes of John Carter or Battleship?) and many we post as news stories, while others offering review discs and invitations to screenings we make decisions about shaped by time and writer availability. Now and then we get offered interview opportunities, and very occasionally we take them. It's not that we are adverse to conducting interviews when offered, but only a handful allow us direct access to the talent in question and some time ago we decided that we'd only conduct interviews if we could shoot them on video. There are a number of good reasons for this, principal among them being that you tend to get more interesting and spontaneous responses when interviews are conducted face to face. This also allows you the flexibility of deviating from your planned questions should something interesting be unexpectedly revealed, or to steer the questioning in a different direction if the interviewee is not responding as expected.

Interviews conducted by email have none of this flexibility and lack the expressive inflexion and body-language that video affords. For the interviewee a list of written questions allows them to formulate a more considered response, but for the interviewer it places a barrier to the sort of interaction that for us makes interviewing filmmakers and actors so enjoyable and revealing. And our Tim asks really good questions, ones that filmmakers respond to and sometimes results in our allotted interview time being extended by the interviewees themselves. You can't get that from a set of emailed questions.

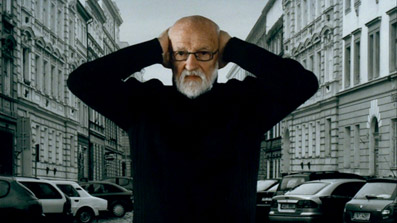

But when I get asked if I'd like to interview someone like Jan Švankmajer and that it will have to conducted by email, everything I just said flies out of the window. Švankmajer is one of only a handful of filmmakers I would confidently call a genius. In the course of his forty-eight year career as a filmmaker he created what I firmly believe are some of the very greatest short films in the history of cinema, surrealistic stop-motion masterpieces like J.S. Bach – Fantasy in G Minor (1965), Dimensions of Dialogue (1982), Virile Games (1988) and Food (1992). His move into features also produced startling results, mesmerising and uniquely toned works such as Alice (1988), Little Otik (2000) and Lunacy (2005). You can get a more detailed idea of just what it is about the work of this extraordinary filmmaker that so excites me by checking out my review of the BFI's 2007 DVD release Jan Švankmajer: The Complete Short Films, a sublime 2-disc set that I cannot recommend highly enough.

So yes, I replied, I'd very much like to interview Jan Švankmajer, even by email. Then came the kicker. Švankmajer agreed to answer our questions, but restricted us to just five. My head started to wobble like that caged nightmare figure in Jacob's Ladder. I had a bucketload of possible enquiries and could easily use all five questions on Dimensions of Dialogue alone and still be left wanting. So what was I to ask? Whatever I came up with I knew for a fact that I'd be kicking myself later for choosing A instead of B or for failing to get the expected response because I didn't choose my words quite carefully enough. And we were up against the clock on this. I've read enough interviews with Švankmajer to already know the answers to many of the questions I'd like to have asked, and a revealing insight into his approach to filmmaking was provided the 1990 BBC documentary The Animator of Prague. And what if all five questions prompted responses simple yes or no answers? Dammit, I needed that interaction and flexibility that comes with video interviews.

In the end I made a simple and perhaps more democratic decision – rather than severely prune my overlong list, I decided instead to ask site readers via Twitter what questions they'd ask and pick the five most interesting responses. So it's all your fault. Yeah, that'll work. The bias towards Surviving Life is inevitable given that it's the upcoming DVD release of that film (alongside earlier features Lunacy and The Conspirators of Pleasure) that prompted the interview offer in the first place. The answers are concise and sometimes brief but are all interesting in their way, and one of them neatly put me in my place for erroneously calling Švankmajer a surrealist filmmaker.

And so to the questions...

1. What films, filmmakers, animators or artists influenced you in your youth?

We all had our gurus in our youth. Due to the fact that I first studied at the Visual Arts School and later at the Theatre Academy, and because my thoughts were not actually occupied by film much, my "teachers" came from the field of visual arts, theatre and literature rather than film. And, because that was the fifties, when Social Realism ruled in Czechoslovakia, my gurus tended to possess the nature of revolt. Within the sphere of theatre it was definitely V. Meyerchold (who died in a gulag). I devoured any mention of his plays and books that I would get in second hand book stores for no-body ever even mentioned his name at school. Within the sphere of visual arts there were the surrealists – Dali, Ernst, Styrsky and Toyen. In the fifties, surrealism was labeled as the "Trojan Horse" of Trotskyism and the surrealists' works were removed from galleries. I first came across Dali's paintings in a Soviet brochure that was translated into Czech, which talked about bourgeois art and had a reproduction of Dali's painting "Three Heads Bikini" to give a deterrent example of degenerate art. Regarding poets, I devoured works by V. Nezval who though, after the war prostituted himself to the system and became a "national author". Nevertheless, he wrote amazing surrealist poetry in the twenties and thirties. In the sixties, when hard-line Stalinism thawed a little bit for a while, I discovered Bunuel's films – L'Age D'or and Un Chien Andalou that I could see at screenings of films from the archives. It was an amazing experience.

2. The films of the Brothers Quay have clearly been influenced by your work. What do you think of their films and do you have a favourite?

I like the Quay brothers' films. They are at least one league better than everything made within animated films in the world nowadays. The Street of Crocodiles is superb. If I were to criticize anything about their work, it would be their exaggerated "artefactilism".

3. You tell us in the opening of Surviving Life that the use of cut-out animation was not an artistic decision but driven by the need to cut costs, but it's hard to imagine it working quite as well any other way. How would you have approached the film if money had been no option?

The film Surviving Life is an example of how an "emergency situation" can develop the imagination. I initially intended to make an ordinary feature film, and using the technique of animated photographs of actors was supposed to cut down the expenses for the film's realization. As we got more money later, I refused to give up this "emergency" technique for it was clear to me that the animated collage technique had enriched the film with yet another imaginative and symbolical aspect that resonated with dreams and psychoanalysis.

4. Do you accept being called a surrealist filmmaker? If not, how would you define your unique approach to storytelling and distinctive cinematic style?

I certainly would not call myself a surrealist filmmaker. One of the main reasons is the fact that a surrealist film does not exist. A. Breton did not write a book about surrealist painting, but he called his book "Surrealism in Painting". Similarly, we should not be talking about a surrealist film but surrealism in film. Besides, I would actually have reservations about the title ‘filmmaker', because I only consider film to be one of a number of means I use in my creative work. It is the same passion that I feel when I draw, build objects, make frottages, collages or I create my tactile experimentations. If the word ‘poet' were not vulgarized, I would call myself a poet for "there is only one poetry and it does not matter which means we use to capture it"( this is my favourite saying).

5. The battle between Freud and Jung in Surviving Life is both hilarious and pertinent. If these two giants of psychoanalysis had to fight it out, who would you put your money on to win and why?

The surrealists have always been Freudians. Even though there is something about the collective unconsciousness, is there not?

Our sincere thanks to Lizzie at Porter Frith – who have patiently tolerated our inability to cover a whole slew of their discs due to our recent shortage of active reviewers – for arranging the interview and the translation of the questions and answers.

|