|

When

I first arrived at art school, many years ago, I had little

knowledge of the many movements that were to become the

backbone of our art history classes. For reasons I cannot

recall, the only one I thought I knew anything about was

Surrealism, and the only painter whose work I was familiar with was Salvador

Dali. I wasn't alone here. Discovering the wonders of

Impressionism, Futurism, the Bauhaus and Dada et al proved

an unexpected joy, but when the time finally arrived for

us to study the Surrealist movement, the class let forth

a murmur of excitement, which was countered somewhat by

our lecturer's audibly weary sigh. This, it turned out,

happened every year, and each time he would have to point

out that there was a lot more to surrealism than Senior

Dali (see the documentary Les Chimères de

Svankmajer below for more on this) and that in

his view Dali wasn't a proper surrealist anyway. We thus

entered this particular phase of the course a little deflated,

but two weeks later I was flying. By then I'd discovered

the paintings of Giorgio de Chirico and Rene Magritte, the writings

of Andre Breton and the genius of Luis Buñuel

via Un Chien

Andalou, his film collaboration with that improper surrealist Salvador

Dali. That two weeks had helped bring into

focus the hazy beauty of the subconscious and the dream

world, or at least the artistic interpretation of it. It

was here that my lifelong love affair with surrealist cinema

began.

It

took me a surprisingly long time to discover my first surrealist-influenced

animated short, and in the subsequent years I came to appreciate

just how perfectly suited this art movement

and this particular medium were to each other. A painting or a sculpture

may be able to capture the essence of a dream, but the moving

image can, in the right hands, evoke the experience. I've

watched a lot of animated shorts that have been at least partly

shaped by the principals of surrealism, but few left me

as gobsmacked as the first one I saw, a film that single-handedly

ignited my collector's fascination with the genre. The film

in question was Dimensions of Dialogue,

the director Jan Svankmajer. If you've seen it then hopefully you'll know

what I mean. If you haven't, then boy are you in for a treat.

But there's more. Much more.

During

the course of his career, the Prague-based Svankmajer has

to date directed a total of twenty-six short films and five features

and has steadily built a reputation as one of the world's

most visionary and respected animators. Like those other

modern masters of animated surrealism, the Quay Brothers,

Svankmajer is a superb technician with a fondness for traditional

stop motion techniques. Signature elements of his films

include lightning fast montages, a distinctive use of clay

animation and 'animated' live action, an inventive incorporation

of found objects, and a fascination with structural decay

and haunted memories of childhood. A distinctive element

of Svankmajer's surrealism is its sometimes dark sense of

humour, from the frustrations piled on the unfortunate occupant

of The Flat and the silent cinema influence

on the otherwise pessimistic A Quiet Week in the

House, to the faux-documentary form of The

Castle of Otranto and the bizarre violence dished

out by the football players to each other in Virile

Games. He comes close to all-out surrealist comedy

in Darkness-Light-Darkness, in which a

body in the process of gradual self-assembly experiments

with a number of curious combinations before getting it

right, the thunderous arrival at the door of excited genitalia throwing the rest of the parts into fearful pandemonium.

There's

a paradox at the core of all surrealist art in which the

deliberately random becomes the subject of analysis and

debate, a search for hidden meaning in a piece that is supposed

to have none. Buñuel and Dali's famous claim of Un

Chien Andalou that "Nothing in this film symbolises

anything" has failed to prevent almost 90 years of

essays attempting to psychoanalyse its images and structure,

but given that this is the imagery of dreams and that dreams

themselves have long since been the subject of psychoanalytical interpretation,

this is both understandable and valid. The same is inevitably

true of Svankmajer's work, although he is more deliberately

up front in some of his symbolism and subtext. There's a

political undercurrent to many of the films that is specific

to its time and place, his sly digs at his country's Communist years

giving way to the all-out assault of the post-Velvet Revolution in The Death of Stalinism in Bohemia. Ironically,

when his work did fall foul of the Communist authorities

it was often the result of their misreading of the film's

artistic elements.

Equally

and often more pronounced are the elements inspired by the

director's personal concerns, fascinations and fears: the

inability of individuals to effectively communicate that

is central to Dimensions of Dialogue; the

sense of false hope that dominates A Quiet Week

in the House; the degeneration of sport into violence

of Virile Games; the rampant consumerism

of Food; the childhood terrors of Down

to the Cellar. This last one in particular Svankmajer

admits is strongly autobiographical – in one of the supporting

documentaries in this DVD set, he recalls that the experience

of being sent down to the cellar of his apartment block as a boy

to collect coal or potatoes was so terrifying that he considered

running away rather than having to repeat it.

Svankmajer's

films exemplify why the animated short needs to

be taken seriously as the premier modern art form, combining

as it does the disciplines of painting, sculpture, collage,

photography and experimental filmmaking to emotional as

well as intellectual effect. As a collection, this BFI DVD

set not only provides convincing evidence to support this

proposal, but also usefully illustrates the extraordinary

variety and scope of this unique filmmaker's oeuvre, making a mockery

of the complaint by one IMDb contributor that Svankmajer

has not progressed since 1971. This is, quite frankly, an

astonishing body of work whose status can be measured by

the fact that you end up judging the films not on how good

or bad they are, but on their relative greatness in relation

to each other.

The

short films are collected on the first two discs of this

set – the third disc is covered in the Extra Features section.

| the films – disc 1: the early shorts 1964-72 |

|

The

Last Trick / Poslední trik pana Schwarcewalldea a

pana Edgara [1964] (11:19)

Svankmajer's first film as director, but you wouldn't know

it from the confidence of the execution. Two doll-headed

magicians take it in turns to perform tricks for the amusement

of an unseen audience and the admiration of each other, the

congratulatory handshake that concludes each demonstration

becoming increasingly harder to break free from. Blending

live action with stop motion, it's recognisably Svankmajer

from the start and a pointer to things to come, from its

production design and lightning fast montage editing to

the degeneration into one-on-one conflict that ends in bodily

dismemberment. Even the opening credits are playfully inventive

in a way that has been borrowed from many times since.

J.S.

Bach – Fantasy in G Minor / Johann Sebastian Bach: Fantasia

G-moll [1965] (9:26)

Music and imagery are stunningly entwined in this ravishing

toccata of decay, as the Bach organ piece of the title is

visualised through images of crumbling walls, decaying doors

and shattered windows, beautifully photographed in scope

framed monochrome and brought to life with rapid camera

movements and animated transformation of their surface materials.

A simple idea, immaculately realised – in the final rapid

corridor tracks the camera seems to become the music.

A

Game With Stones / Hra s kameny [1965] (8:36)

An honest title for a playful animated experiment with variously

shaped and coloured stones, which are spewed from a clock

once an hour and engage in a series of dances to the tinkling

of the clock's own in-built music box. An enjoyable piece

that feels more like an early film than the two that precede

it, the sort of project budding animators test out their

skills on. One sequence involving small stones used to make

up human faces clearly anticipates the later Dimensions

of Dialogue.

Punch

and Judy / Rakvickarna [1966] (9:54)

One of the first Svankmajer films I saw (under its alternative

title of The Coffin Factory) and one of

his few early films to have even a semblance of a linear

story. Punch and Judy expands on the grotesquery

and violence of the character of Punch (I've never understood

why kids aren't completely freaked out by this horrible

creature) and his destructive conflict with his partner,

something that Svankmajer seems to have enjoyed exploring.

Et

Cetera [1966] (6:58)

In visually arresting shadow puppetry style, Svankmajer

toys with notions of freedom, obedience and capitulation,

the shifting and corrupting nature of power, and conflicting

desires for security and independence, all particularly

relevant to the time and place in which the film was made.

Historia

Naturae, Suita [1967] (8:38)

A brilliantly edited celebration of the beauty and complexity

of various animal species, which man, it is suggested, collects,

imprisons, preserves and consumes. One of Svankmajer's most

overt early political statements.

The

Garden / Zahrada [1968] (16:09)

Svankmajer confirms his surrealist credentials with this

live action story of reunited old friends, one of whom accompanies

the other to his quiet house in the country to find it surrounded

by a 'living fence', an unbroken ring of people with linked

hands and stare-ahead faces. A genuinely dream-like concept

with inescapable political overtones – many of those in

the fence are dressed in the clothing of service occupations,

workers in servitude to a landowner master, who cares nothing

for their welfare and demands their unquestioning obedience.

There is a dark inevitability to the ending, but that doesn't

make it any the less chilling, and the visiting Frank's habit

of nervously combing his hair is later used to subtly comment

on the nature of authority within a system based on power and

class.

The

Flat / Byt [1968] (12:34)

A blackly comic surrealist nightmare that leads a young

man into a room whose contents all disobey real world logic

– water escapes from a gas stove, stones pour from a tap,

a crooked picture cannot be adjusted without the one above

it shifting, and a swinging light bulb punches a hole in

the wall from which a wooden fist emerges to assault

the curious. An attempt to eat is similarly frustrated by

a soup spoon riddled with holes, a fork that bends out of

shape, a beer glass that reduces to thimble size when raised

to the lips, and an egg that falls through the table and

is swallowed by a wall when thrown at it. A direct link

with the surrealist movement is provided by a man who emerges

from a wardrobe dressed in a Magritte-style bowler hat and

a mirror that displays the back of the head rather than the

face looking into it, recalling both Magritte's Not

to be Reproduced (1937) and Dali's My Naked Wife

Watching Her Body (1945).

Picnic

with Weissmann / Picknick mit Weissmann [1968]

(10:41)

In a woodland clearing, a man's possessions and furniture

enjoy a quiet few hours without him. 78rpm records play,

a chess board engages in a game with itself, three chairs

and a dresser play football, a plate camera takes portraits,

and a pair of pyjamas lounge on a bed and eat plums. Meanwhile,

a shovel busies itself digging a large, rectangular hole.

The surrealism of dislocating objects from their normal

environment is explored to seemingly playful effect, but

there's a dark twist to the tale that allows for a number

of readings of what has gone before.

A

Quiet Week in the House / Tichy tyden v dome [1969]

(19:13)

A man on the run or a secret mission into enemy territory

(it's never specified) enters an old house and sets up

camp in a corridor. Every day he drills a new hole in the

wall, through which he witnesses a series of strange visions,

from a clockwork bird that escapes its tether to eat only

to be subsequently buried and dismembered, to a hanging jacket that siphons

water from a vase and then urinates on the floor, leaving

thirsty plants to spontaneously combust. Images of destruction

and false hope run throughout, the final act suggesting

direct political allegory (and you can read plenty into

the tongue that is minced into small rolls of printed typeface),

and yet Svankmajer still manages a final moment of typically

perverse surrealist humour. Stylistically, this is an unusual

piece in Svankmajer's canon, the vérité-style

camerawork, projector sound and exaggerated edit splices

of the live action contrasting with an animation style that

blends stop motion with optical dissolves.

Don

Juan / Don Sanche [1969] (31:20)

A version of the Don Juan legend performed by oversized

marionettes that is in some respects one of Svankmajer's

most atypical early films, the surrealism confined to the

the puppetry and Don Juan's creepy night time confrontation

with the ghost of the murdered and faceless Don Avenis.

It's still an intriguing piece for its blending of real

locations with the artifice of a stage production (sometimes

in the same shot), the combination of performance and altered

frame rate to make actors move like marionettes, the use

of decayed and crumbling architecture and the urgency of

some of the camerawork.

The

Ossuary / Kostnice [1970] (10:06)

A visually startling trip through the Sedlec Ossuary, an

extraordinary Roman Catholic chapel decorated with the bones

of over 40,000 human skeletons, largely victims of the Black

Death in the 14th century. It's the sort of place that even

a straight documentary would render bizarre, but

Svankmajer's approach – all sudden camera movements and

lightning edits – imbues it with a particularly nightmarish

quality, images caught fleetingly that prove cumulatively

overpowering. The

original soundtrack consists of the voice of a female guide

cheerlessly giving a group of schoolchildren a tour of the

Ossuary and becoming increasingly impatient at their inability

to obey the 'don't touch' rule, even imposing an on-the-spot

fine on one unfortunate. It's a fascinating aspect of the

film that both compliments and counterpoints the visuals,

its continuous flow at deliberate odds with the fractured

editing style, but fleetingly in sync with the speech, as

when the guide complains of the graffiti that has been drawn

on the bones is married to the image of a series of skulls bearing the signatures

of past visitors. For reasons known best to

the authorities of the time, this soundtrack was considered

in some way subversive and a new track was commissioned,

a strangely (and intermittently effectively) at-odds piece

of lounge jazz, preceded by a short history of the Ossuary.

Here the editing feels less jarring than on the original

version, due in no small part to our own experience with

the sometimes frantic visuals of music videos, where music

provides a glue that natural sound cannot. Both versions

are included here, and despite the intriguing strangeness

of the music track, I'll go with the original every time.

Jabberwocky

/ Zvahlav aneb Saticky Slameného Huberta

[1971] (13:20)

Taking inspiration from Lewis Carroll's famous nonsense

poem rather than attempting to visualise it, this is an

imaginative tour-de-force that goes some way to defining

what could vaguely be described as the Svankmajer style,

from its realistic figure animation to the use of varied

materials and techniques. It's the sort of film that at

first seems deliberately random in its imagery and yet invites

detailed analysis of every scene, its play on childhood

memories and abstract fears as pure an expression of animated

surrealism as Svankmajer had delivered up to this point

in his career.

Leonardo's

Diary / Leonarduv denik [1972] (11:16)

Svankmajer switches materials again with this rare venture

into traditional 2D drawn animation, but typically combines

it with 3D stop motion to repeatedly crumple the paper on which the

images appear. The drawings here are all based

on Leonardo Da Vinci's own and are beautifully rendered

and animated, the relationship between the animator and

his inspiration established by a pencil that draws a hand

that then takes over the process of creation. The intercutting

of animated historical battles with footage of modern street

riots gives the film a political undercurrent that once

again landed Svankmajer in trouble with the powers that

be, resulting in a seven year absence from the director's

chair.

| the films – disc 2: the later shorts 1979-92 |

|

The

Castle of Otranto / Otrantsky zámek [1979]

(17:15)

The playful humour than runs through much of Svankmajer's

work shifts up a step as reporter Milos Ryba interviews

archaeologist Jaroslav Vosáb about his theories regarding

Horace Walpole's 1764 gothic novel The Castle of Otranto.

The live action mockumentary footage is intercut with sequences

from the novel, brought to life through Terry Gilliam style

cut-out animation of the book's illustrations, complete

with captions and page reference numbers. Typically fast

paced, it builds to a supernatural punchline which the final

shot of Dr. Vosáb appears to amusingly deconstruct.

The

Fall of the House of Usher / Zánik domu Usheru

[1980] (15:02)

The first of Svankmajer's two Edgar Allen Poe adaptations

hooks into the original story's sense of gloom and decay,

the latter a favourite theme of the animator's and one that

becomes the key focus of this richly atmospheric trip through

the Usher house. Beautifully toned monochrome photography

recalls the destructive imagery of Fantasy in G

Minor and The Flat, while a combination

of object manipulation and superb clay animation creepily

evokes the atmosphere of the story without ever showing

any of the human protagonists.

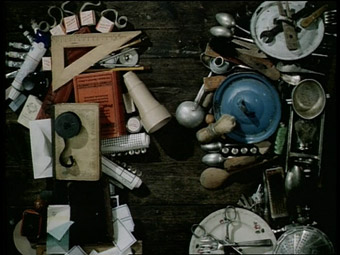

Dimensions

of Dialogue / Moznosti dialogu [1982] (11:18)

One of the most perfectly realised of Svankmajer's short

films, Dimensions of Dialogue is a brilliant

riff on the consequences of humankind's inability to effectively

communicate. The film is divided into three titled sections. The first, Factual Dialogue, is one of the director's most

technically complex pieces, a twist on the Rock-Paper-Scissors

game in which human heads constructed from different everyday

materials (kitchen implements, fruit and vegetables, stationery

items and tools – the practical, the organic and the artistic,

all key elements of modern human existence) are swallowed

by each other, chewed up and spat out to reform from the

damaged material, which then moves on to inflict similar

damage on another. In the second, Passionate Dialogue,

perfectly sculpted clay figures of a man and a woman touch,

kiss, embrace and dissolve into a rippling torrent of sexual

pleasure. When they emerge they have created an offspring,

an unformed clay blob that neither of them want and that

becomes a weapon in their rapidly deteriorating and physically

destructive relationship. In Exhausting Dialogue,

the clay heads of two middle-aged men produce complimentary

objects from their mouths, a sharpener for a pencil, paste

for a toothbrush, laces for a shoe, butter for bread. Their

mutually agreeable dialogue soon falters, however, as the

same objects are mismatched and inflict damage on each other,

leaving both heads crumpled and exhausted. This is surrealism

with purpose, the message always clear but delivered with

a skill and imagination that is genuinely touched by

genius.

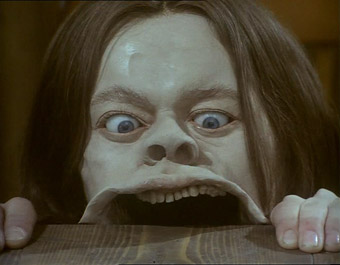

Down

to the Cellar / Do pivnice [1983] (14:44)

A young girl is sent down to the cellar of her apartment

block to collect potatoes from the crate in which they are

stored. It's a journey filled with strange terrors, including

a man who sleeps in a bed of coal and offers her rest for

the night, a woman who makes cakes from coal dust, potatoes

that leap from her basket and make their own way back to

their crate, and a giant and fearsome-looking cat. The most clearly

autobiographical of Svankmajer's films is also the one that

that speaks most directly to the childhood fears of its

audience, awakening memories of a time when surrealism was

not just confined to the dream world, but part of imagination-fuelled

everyday life.

The

Pendulum, The Pit and Hope / Kyvadlo, jáma a nadeje

[1983] (14:20)

Svankmajer's second Poe adaptation is a genuinely disturbing

retelling of The Pit and the Pendulum, one that puts

the audience inside the head of the tale's unfortunate protagonist

to create a completely subjective experience. The atmosphere

of twisted horror is heightened by Eva Svankmajerová's

production design and Miloslav Spála's high contrast

monochrome camerawork.

Virile

Games / Muzné hry [1988] (14:01)

A man lines up the beers and the biscuits for the big football

match on TV in which the players win points not for scoring goals

but for fatally and spectacularly assaulting each other.

Clearly a comment on violence in sport and spectator reaction

to it (fans cheers wildly at the match while the viewer

indifferently drinks another beer, even when the

action spills over into his flat). There's nonetheless a wonderfully

perverse humour to the on-pitch ballets, the extended half-time

bathroom break and the grimly creative methods the players

use to dispatch each other, a tit-for-tat battle that you

can't help thinking had at least some influence of Bill

Plympton's 1991 animation Push Comes to Shove.

Another

Kind of Love [1988] (3:35)

Another rarity for Svankmajer, a music video for Stranglers'

ex-front man Hugh Cornwell, one that's busy with imagery both

familiar and new, and despite the song's upbeat melody there's

a pleasingly dark sense of a man trapped in a room of his

own memories and fantasies, physical contact with which

results in him being pulled into the wall and out of physical

existence. All that's missing here is an explanation of

how the hell Hugh Cornwell, of all people, was able to persuade

one of the world's greatest animators to illustrate his

song.

Meat

Love [1988] (1:07)

A visual gag in which two steaks cut from a beef joint enjoy

a brief flirt before their intimate roll in the flour lands

them in the frying pan. A subtextual element is nonetheless

evident, and the animation alone is a delight.

Darkness-Light-Darkness

/ Tma/Svetlo/Tma [1989] (7:13)

Various body parts arrive in a small room and innocently

attempt to find a logic to their assembly, alternately curious

and fearful at the arrival of more. Beautifully sculpted

and animated, this is one of Svankmajer's most overtly playful

and wittily comedic films, but it still ends on a note of

claustrophobic, surrealist horror.

Flora

[1989] (0:31)

A body made of vegetable material and tied to a bed is rapidly

decaying, unable to reach the nearby glass of water that

may just save its life. Just thirty seconds long but still

visually startling and packed with subtext about the age,

encroaching decrepitude, and our own role in the cycle of

nature.

The

Death of Stalinism in Bohemia / Konec stalinismu v Cechách [1990] (9.24)

Post-Velvet Revolution Svankmajer dumps the subtle approach

for his most up-front political statement, a self-proclaimed

"work of agitprop" that provides a fragmented

political history of Communist Czechoslovakia. Subtle it ain't

– workers moulded from clay on a production line are

then executed and dumped for recycling; the flag of the

Czech Republic is painted on every every surface in a run-down

workshop; rolling pins crush everything in their

path – but artistically thrilling it most definitely is.

If you don't know your Czech political history then it should

at least prompt a little post-film research.

Food

/ Jídlo [1992] (16:22)

Adopting the three-act structure of Dimensions of

Dialogue, Food is a wonderfully

designed and consistently witty exploration of human consumption,

both literally in the items ingested and metaphorically

in its digs at greed and social division in an increasingly

disposable society. Breakfast is a nightmarish

riff on both the fast food culture (the first McDonald's

restaurant opened in Prague in March of 1992) and humankind's

role in the food chain, with diners feeding

before being transformed into dispensing machines for the next customer.

Snobbery and the new social divisions get a dig in Lunch,

as a sniffy businessman and an unkempt youth repeatedly

fail to attract the attention of a resturant waiter and take to eating the plates, their clothes and even the

furniture, but it isn't destined to stop there. In Dinner,

a large gastronome spends forever adding condiments to a

dish that has been very specially prepared just for him,

a sly dig perhaps at self-destructive modern lifestyles

and eating habits. Technically Food one

of Svankmajer's most impressive achievements to date, the

switch from live action to claymation so perfectly executed

that the join is genuinely invisible. By the way, the bearded

gentleman who sits down for breakfast at the end of the

first sequence is the film's animator Bedrich Glaser.

Svankmajer's aspect ratio of choice has almost always been 1.33:1

and the majority of the films here have thus been so presented,

the notable exception being J.S. Bach – Fantasy

in G Minor, which was shot in scope and has been

anamorphically enhanced for this release. All of the films

are genuine PAL remasters, and despite the age of some and a few

dust spots here and there, this is far and away the best

you've ever seen any of them look, and I'm including Kino's

US Svankmajer short film collections. Sharpness is generally

excellent and colour and contrast are just right, the black

levels always coal-cellar perfect. The tonal beauty of the

greyscale images in the monochrome films is particularly

well captured, the high contrast look of a couple of them

clearly deliberate. Detail is just a tad softer on two or

three of the films (Meat Love is probably

the most noticeable), but the picture quality otherwise

remains high.

The extra features are also nicely presented, although Johanes

Doktor Faust is non-anamorphic scope and to keep

the picture clear the subtitles are in the border area.

This should cause no problems on LCD and plasma TVs, but

depending on the overscan of your CRT widescreen you may

lose a little information when there are two lines of text,

unless you have a subtitle zoom mode. Otherwise the picture

quality is fine. The Lunacy trailer is

anamorphically enhanced widescreen.

The

soundtracks are largely Dolby 2.0 mono and always clear

– a little fluff and crackle is audible on Down

to the Cellar, there's a bit of a hum on Johanes

Doktor Faust, and there are a couple of pops on

the soundtrack of The Castle of Otranto.

Food has a very nice stereo track, and

both the Chez TV interview and the Lunacy

trailer are also in stereo.

Johanes

Doktor Faust [1958] (17:23)

Directed by Emil Radok, this is the first film that has

Svankmajer's name in its credits and one he remains proud

of. A retelling of the Faust story with puppets "made

by an old family of puppeteers," it foreshadows Svankmajer's

own work with its smart use of camera angles and movements,

its effective mixing of animation styles, its sometimes

unsettling dreamlike imagery and its excellent montage work.

Svankmajer, of course, was later to make his own version

of Faust in 1994.

Nick

Carter in Prague / Adéla jeste nevecerela

[1977] (5:00)

Three extracts from a longer work made during the post-Leonardo's

Diary period when Svankmajer abandoned directing

and worked instead on other people's films, here creating

a giant carnivorous plant that would not be out of place

in The Little Shop of Horrors.

The

Cabinet of Jan Svankmajer [1984] (53:36)

A documentary directed for Channel 4 on Svankmajer by the

Quay Brothers' regular producer Keith Griffiths, with animated

inserts from the Quays that were compiled into a short film for

inclusion on the BFI's Quay

Brothers Short Films DVD. Here those same sequences

are beguilingly used in place of interviews that Svankmajer

was apparently unwilling to give, cut with extracts from

his films (almost all of Dimensions of Dialogue

is included) and interviews with a number of art historians,

surrealists and critics. Animated links and revealing quotes

from Svankmajer aside, this is a slightly academic affair,

thanks in part the middle-class dryness of the interviewees

– they know their stuff, but I wouldn't want to be stuck

in a lift with any of them.

Les

Chimères de Svankmajer [2001] (58:18)

Shot during the making of the feature film Little

Otik and the creation of the 1998 touring exhibition

Anima Animus Animation, this is an enthralling and revealing

peek at the creative partnership between Svankmajer and

his wife Eva Svankmajerová. Both appear comfortable

with the camera's presence and talk freely about their past

and present work, and there are some priceless comments here, from Jan's determination to convince young people

that there's more to surrealism than the paintings of Salvador

Dali (ah yes, well...) and his recollection of his childhood

terror of cellars, to Eva's observation that ten years after

the fall of communism they are all now encouraged to be

only interested in money, which is just as bad. The behind-the-scenes

material on Little Otik is particularly

welcome. Terrific.

Czech TV Interview (2001) (8:58)

A brief interview conducted with Svankmajer as part of a

Czech TV series The History of Painting and Sculpture that includes some of his artwork and a useful overview

of Eva Svankmajerová's paintings. I was particularly

caught by Svankmajer's assertion that the common denominator

to what he does in his work is "the game."

'Lunacy'

Trailer [2005] (3:04)

A trailer that leaves you wondering just what the film

as a whole must play like, but that intrigues nonetheless.

Booklet

The

final extra is not on any of the discs, but takes the form

of a handsomely produced booklet containing a number of

quality stills and an informative essay on every film and

extra in the set.

What

can I say? A genuinely remarkable body of work, all splendidly

remastered and collected together in a wonderfully comprehensive

3-disc set. Even if you have a substantial number of these

films on other formats or even DVD, this is a must-have,

and if you are seriously interested in either animation

or surrealism or both, then consider this an essential purchase.

Absolutely bloody marvellous.

|