| |

"Christiane recalled asking her husband during the last phase of 2001's production if he was worried about getting the film done. The director's response had been "No, I'm not worried because I have Doug." |

| |

P. 402, Space Odyssey by Michael Benson |

Now, none of us has Doug.

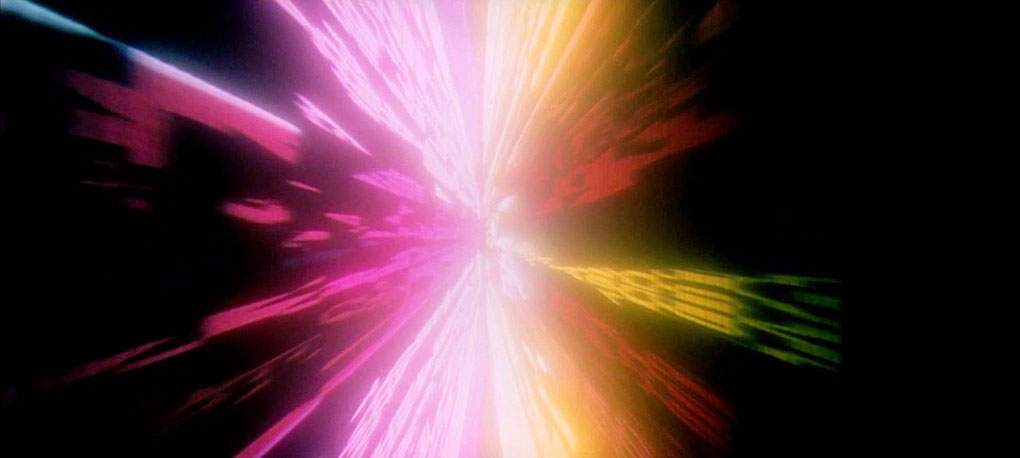

Arguably the greatest special effects man of all time died on the 7th February 2022. The images he fashioned and produced for a small number of lucky directors punctuate powerfully throughout my entire cinema-going years. His work is part of the reason I took a certain path, one I am still on. 2001: A Space Odyssey changed the course of my life as it did the unworldly 23 year-old lucky enough to be mentored by Stanley Kubrick over the years it took to bring that astounding work to fruition. He'd worked as a do-it-all air-brush artist and technician on a NASA corporate film entitled To The Moon And Beyond for the World's Fair in 1964. A certain Stanley Kubrick saw the film and realised that his vision of the 'first good science fiction film' wasn't pie in the sky. It was achievable. Trumbull managed to get Stanley Kubrick's home number, pitched himself and his work which he knew Kubrick admired and was hired on the spot. For both men, it was a great decision and for cinema itself, it was a blessed pairing. The astounding 'star-gate' sequence, perhaps 2001's most famous scene, is entirely Trumbull's creation. Kubrick, a creative force to be reckoned with to be sure, was more of an artful shopper of ideas than a man with the entire film in his head trying to stop compromises ruining what he had in mind. To that end he was partially dependent on those he chose to work with. His wife clued him in to the ethereal sounds of composer György Ligeti after hearing his compositions on the radio and Trumbull delivered the 'star-gate'. Kubrick took full credit for the special effects of his greatest movie (and therefore took the Oscar home), something that didn't sit right with Trumbull but both men knew how important they were to each other.

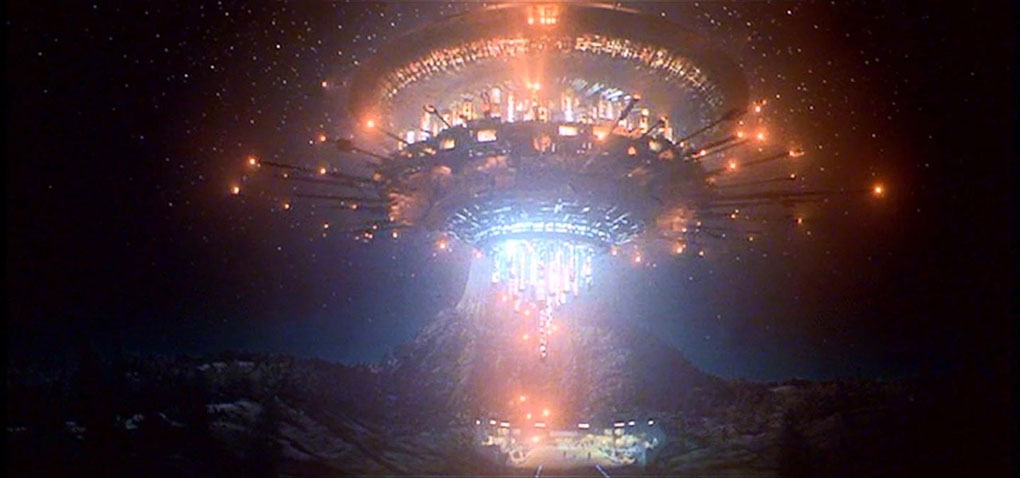

Skills inherited from his father perhaps (who did the special effects for The Wizard of Oz), Trumbull was both an artist and an engineer (both traits mixed together make a filmmaker). He managed to create practical ways to get the most life-changing visuals on to the screen. I say that with no irony or hyperbole. As the mothership is revealed in all her magnificent glory in Close Encounters of the Third Kind, the sight elicited a profound emotion in me that has never been recreated but never forgotten. I stared into the starry sky very late (or very early) on the 2nd April 1978, my 17th birthday, after first seeing the film at a midnight preview and just repeated the words "I don't believe it…" I saw the film three times the next day and almost got to 30 theatrical viewings before it left the cinema.

Trumbull was also a director and in this capacity is famous for the ecological science fiction mini-classic, Silent Running (which I reviewed here). But the film that was life changing in all the wrong ways was Brainstorm. Trumbull had created an alternative cinema experience with his high frame rate 'Show Scan' process which blew Paramount executives away on being immersed in it at a test screening. Brainstorm was to be the first film made for that process. Two things scuppered the ambitious project; the cost of outfitting theatres with the new technology and the premature and mysterious death of his leading lady Natalie Wood. Trumbull cited this as an event that gave him post-traumatic stress disorder and it took a year or so for him to recover. After working six months 24/7 on getting the 650 effects shots completed for Star Trek The Motion Picture, he was hospitalised, ulcered and exhausted. What took him to his next major project was the desire to leave space behind.

In the summer of 1982, both Slarek and I attended a sneak preview of Ridley Scott's latest film, an adaptation of author Philip K. Dick's Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? To say we were staggered by the opening sequence of Blade Runner may be an understatement of momentous proportions. Trumbull's exquisite work on the special effects of that film is, with 2001, at the very zenith of photo-chemical special effects work. A showreel of these effects was screened for the author of the original novel and stunned by the experience he asked Scott and Trumbull how on Earth could they have known what images he had in his head for the story? Trumbull said in the documentary about his career, Trumbull Land, that this was praise of the highest order.

Trumbull found it difficult dealing with people in Hollywood and opted out of filmmaking until tempted back by Terrence Malik to work on Tree of Life. He was quoted as saying "Perhaps I was out of my mind!" for even trying to produce good work in the Hollywood system. His work will live with me until my own demise for its emotional impact as much as its wow factor. If you want to celebrate this giant in Hollywood, get hold of a 4K copy of 2001: A Space Odyssey and just revel in the genius that was Douglas Trumbull.

He has now gone, to quote 2001 'beyond the infinite'. RIP, Douglas Trumbull.

|