|

When I was just a lad, the general consensus amongst the politically active was that the world would probably end in a firestorm of nuclear explosions and that it would probably happen soon. As the cold war unexpectedly but thankfully thawed, the spectre of nuclear war faded and the supervirus found itself promoted to the position of most likely cause of humanity's destruction. It's a still relevant fear at a time when new viruses continue to appear and older ones evolve whist human evolution appears to moving backwards, with more and more people seem willing to reject science and proven fact and take a more troglodyte approach to what barely counts as reason. Partly as a result of this embracement of ignorance, the threat of nuclear annihilation is back on the table.

Books and films in which humankind is devastated by a virulent pandemic are now numerous and distinctive enough in their narratives and iconography to constitute their own subgenre, one that Kim Newman neatly categorises as Decontamination Suit Films. The popularity of these tales is hardly surprising, as while it's possible to convince yourself that you could outsmart and hide from a rampaging alien monster, protecting yourself from something you cannot see or hear and that you can lose an invisible battle against by doing something as simple as breathing is altogether scarier. It's also something we all have real-world experience of from that time we were surround by coughing and sneezing family members and when, despite making every effort to shield ourselves from their airborne germs, we ended up catching their cold regardless. The only real protection against a killer virus is an effective antidote or something that will neutralise the virus in question, and for that we have to put our faith in science and scientists. Before you get your hopes up, however, it's worth remembering that after decades of research, not one of them has found an effective way of protecting you from that cold your relatives thoughtlessly passed on to you. And that's a common virus that's been on this planet for who knows how many centuries. What if the virus in question was alien in origin? Any team tasked with looking for a cure would effectively be starting from scratch with a lifeform they have no previous practical experience of. Where do you start?

The peculiar appeal of apocalyptic science fiction stories (and video games, I should note, except bloody Fallout 76) is a subject for a separate article or even a weighty book, but that appeal is very real and these are stories that I am also irresistibly drawn to. You could argue that Michael Crichton's 1969 novel The Andromeda Strain does not technically fall into that category as its virus is confined to a single location and has not yet become the widespread infection that has become a subgenre standard, but the potential for it to do so is always present and we're left in no doubt that the consequences for the population at large could be catastrophic if it did. The 1971 film of the same name is, for the most part, an impressively faithful adaptation, the only major change made by screenwriter Nelson Gidding being to switch the gender of one member of the previously all-male team to better reflect the make-up of the real-world scientific community, a decision that Crichton heartily approved of.

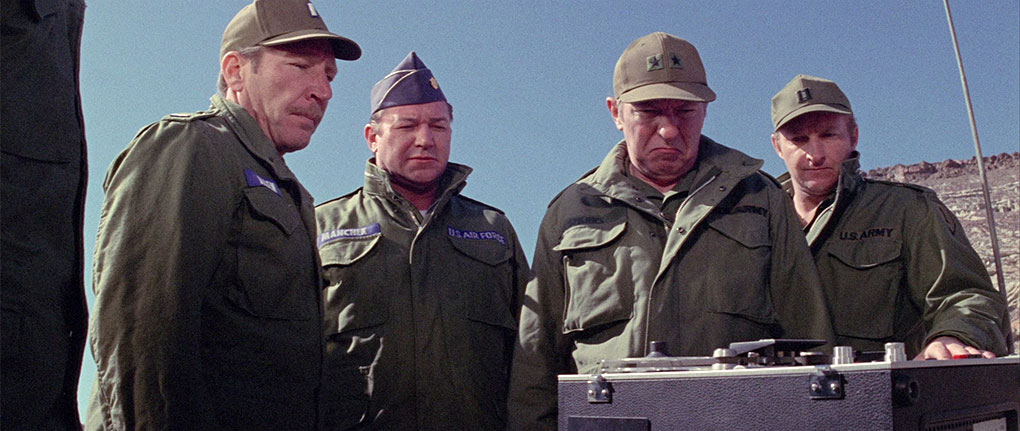

Following a caption that suggests the film is based on actual events (it isn't, but it could have been, if you get my drift), the story kicks off in eerily ominous fashion, as a soldier quietly observes the town of Piedmont, New Mexico, from a distant vantage point at night through an infrared scope, then joins his colleague in a van whose rooftop radar has pinpointed the town as the location where a government satellite, part of an operation known as Project Scoop, has fallen to Earth. The town is eerily quiet even for this late hour and the soldiers notice that it is being circled by buzzards, predatory birds that do not usually fly at night. They report their findings to the Scoop control centre at Vandenburg Air Base and are ordered to proceed to the town and retrieve the satellite.

This whole sequence is handled with an almost documentary lack of sensation and fuss, which proves to be the film's first small but still significant masterstroke. The second immediately follows, when the soldiers head towards the town and instead of going in with them, the film stays in the Vandenburg control centre, where the soldiers' progress is monitored through their radio communication. So much about the storytelling economy and tension-building of this sequence is quietly excellent. We know instantly, for example, that the retrieval of the satellite was expected to be a routine and hitch-free operation by the fact that the project controller converses with the soldiers whilst lounging casually in his chair and reading a magazine, and we know instantly that the soldiers' observations have serious implications by a sharp shift in tone of the controller's response and the concerned facial expressions of other control room staff, who are soon hanging on the every transmitted word. The soldiers' voices, meanwhile, are given visual representation through closeups of oscilloscope waveforms of their voices , a nifty way of gifting them a proxy physical presence that really pays off when they start seeing bodies and then spot something they do not have the chance to accurately describe before their transmission is cut short by a terrified scream.

Two phone calls later and a team of four civilians have been given security clearance and are being smartly rounded up by the military. Once again, storytelling economy is laced with mystery, as a dinner party hosted by Dr. Jeremy Stone (Arthur Hill) is interrupted by the arrival of two imposing-looking military personnel, who rattle Stone's unknowing wife Allison (an uncredited but convincingly troubled Susan Brown) when she answers the door. Her POV of these unwelcome visitors tells a story in itself, with the stony faces of Captain Morton and his burly-looking sergeant framed in discomforting close-up on opposite sides of the scope frame, while pacing the road beside a car in the background – a depth of focus achieved through a canny use of a split-dioptre lens (it won't be the last) – is a soldier with a rifle slung over his shoulder. Coupled with the matter-of-fact nature of visitors' dialogue, this extraordinary shot tells us one thing very clearly, that these men have come for Dr. Stone and he is going with them whether he likes it or not. The thing is, although he clearly wasn't expecting their arrival, he was nonetheless ready for it, and the urgency, secrecy and importance of their assignment are all subtly communicated by the following carefully coded exchange:

| |

Stone (to Captain Morton): "I'm Doctor Stone." |

| |

Morton checks a photo in his hand before confirming. |

| |

Morton: "Yes. I'm Captain Morton. There's a fire, sir." |

| |

Stone pauses briefly for thought and then turns to his wife. |

| |

Stone: "I've got to leave." |

He's out the door in seconds and when the bemused Allison tries to phone her senator father to find out what's happening, the call is interrupted by a coolly officious female voice that informs her that the conversation has been terminated in the interests of national security.

The other three members of the team – Charles Dutton (David Wayne), Mark Hall (James Olson) and Ruth Leavitt (Kate Reid), each of them eminent doctors in their particular fields – are all collected with similar cinematic efficiency, and it becomes clear that of the four only Stone and Dutton were previously aware that they could be called up if specific circumstances arose. Hall, a surgeon, is forced to abandon an operation he was already scrubbed up for (something he expresses his frustration at by pausing on his way out and pulling down his mask in frustration in the film's only overly melodramatic moment), while the cantankerous Leavitt is midway through an experiment and initially refuses to accompany the officers sent to collect her, at least until one on them expresses concern for her health when she shows signs of fatigue, a subtle bit of telegraphing for a plot point that will later become problematically relevant.

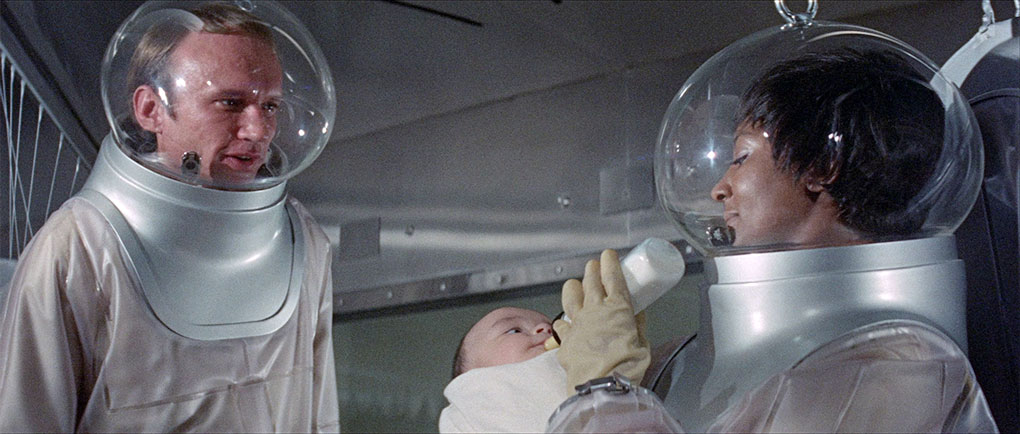

Stone and Hall are then transported to Piedmont in hazmat suits to retrieve the satellite, after first dropping gas to kill birds (it only works on birds we are informed, a slightly clunky piece of exposition designed to deflect questions about what will happen next) that are eating the flesh of the bodies that are lying in the streets. They do this to stop the birds from flying off and spreading the infection, which makes perfect sense, but by this point we're almost a full day into the crisis, which does feel a little like slamming that stable door after at least some of the horses have flown. What follows is a sequence that haunted me in my younger days and still has the power to creep me out today. The bodies of the town's late residents are everywhere, having seemingly fallen where they stood, suggesting a virulent disease that killed them all instantly, a theory that is then discomfortingly usurped when Stone and Hall find bodies of people who had time to take their own lives before the virus could claim them. The image that burned itself into my brain on my very first viewing of the film, however, comes with the realisation that the virus is clotting the blood of its victims, a discovery jarringly illustrated when Hall cuts the wrist of one of the bodies and blood pours out of the wound in powdered form, a practical effect that still convinces today and looks horribly real even in HD. The real surprise, though, comes when the two men discover a crying baby that appears to have been unaffected by the virus, and just as they are loading it onto a helicopter for transport, a grizzled and angry old man appears from nowhere and blames them for wiping out his town before collapsing in pain. These two survivors and the satellite are then transported to a secret underground facility named Wildfire constructed specifically for this eventuality, in which is a shielded laboratory where Stone and his team are tasked with finding the virus that laid waste to Piedmont, studying its structure and discovering a way to neutralise it and its effects.

Before I go on I should perhaps mention that The Andromeda Strain was directed by Robert Wise, a rightly revered filmmaker who, as Kim Newman points out on this disc, was not known for a particular genre or even for a specific cinematic style, but whose filmography includes its share of bona fide classics, including an earlier science fiction masterpiece, The Day the Earth Stood Still. Apparently something of a fan of the genre, Wise was attracted to the project by Michael Crichton's novel and was clearly as fascinated with the science and technology of the story as its then young author. As noted above, he and his cinematographer Richard H. Kline show a real talent for framing shots in a manner that contributes to the storytelling, and their use of wide shots and split-dioptre lenses is particularly effective and intermittently striking. They also make arresting use of Boris Leven's consistently impressive production design to showcase a facility whose futuristic look works in harmony with its practicality and always feels grounded in the scientific and technological reality of the day. Not always as successful are the experiments with split-screen, which are effective when used to provide a visual representation of the layout of Wildfire as discussed by Leavitt and Dutton as they descend to its lower levels, but which stumble a little when used to get inside the meditating Leavitt's head. Then again, it doesn't help that this montage includes a bearded, German-accented scientist who puts his hands on his hips and says with almost comical ham, "Fools! They refuse to believe life exists in meteorites!" while Leavitt watches on dispassionately with her hands in her lab coat pockets.

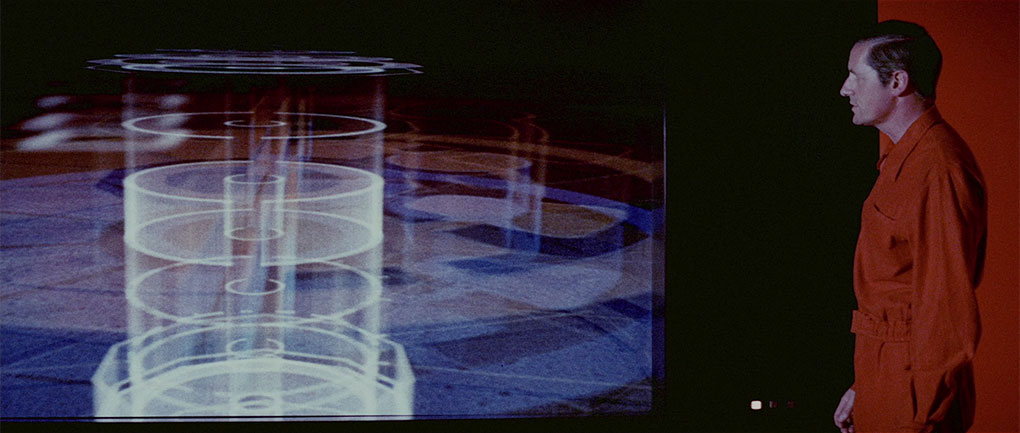

It's when the team first arrives at Wildfire that Wise changes gear in a manner that on paper should grind the film to a halt but somehow doesn't. Instead of scooting us rapidly through the various decontamination and immunisation procedures that are required of the team in the economical manner of the previous half-hour, Wise takes us through them each of these processes in unhurried detail, explaining their purpose and making the most of the opportunities they offer to create a series of intriguing other-worldly visuals. Astonishingly, these procedures and the team meetings that follow each stage occupy a seemingly logic-defying 25 minutes of screen time, little of which is spent advancing the plot and which seems to be more about giving the audience a flavour of just how difficult it is to decontaminate the human body, whilst at the same time drip-feeding the sort of expositional information we will need to fully get to grips with what is to follow. And yet not for one second does it feel drawn out or remotely laboured. How many filmmakers would have taken this risk and pulled it off with such aplomb?

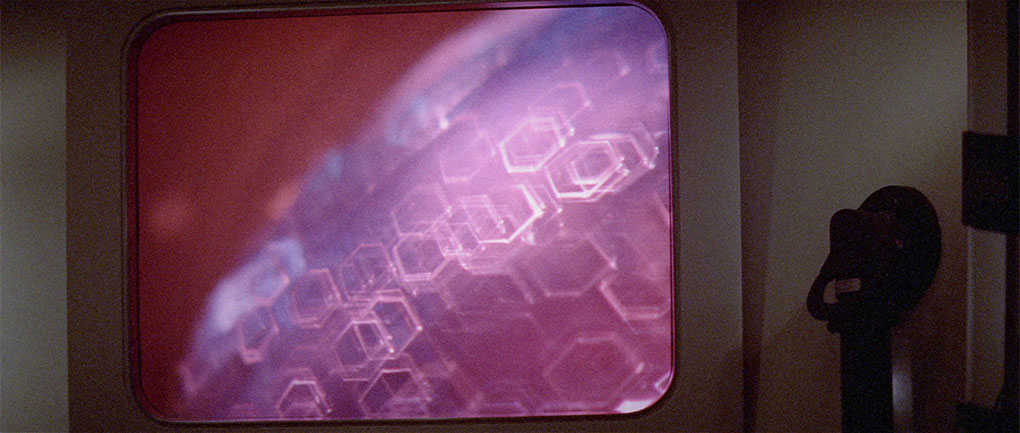

Taking us through the decontamination and immunisation process in such detail also helps to makes us feel like part of the team, and as the search for the microorganism kicks off, the film does an bang-up job of communicating both the tiring repetition that comes with dogged experimentation and the excitement and alarm that a breakthrough can trigger. When the team does locate the organism, the electro-microscopic imagery of it is disarmingly convincing, a semi-abstract blob of organic matter whose every pulsing spurt of growth requires the lens on microscope to refocus (that's such a nice touch), one of several remarkable special effects created for the film by the great Douglas Trumbull, still fresh from his ground-breaking work on 2001: A Space Odyssey and shortly to direct his own science fiction classic, Silent Running. The study of a life form we already know is lethal is peppered with intrigue and tension (though beware, animal lovers may have a problem with one experiment, which although faked under the watchful eye of the American Humane Association, clearly caused one animal some distress), while the very notion that something so infinitesimal could lay waste to an entire town in a matter of seconds makes what could be the smallest alien invader in science fiction film history one of the most terrifying.

Every step of the team's investigation makes for riveting drama, taking on the air of a mystery thriller with potentially apocalyptic consequences for failure, and playing out against the threat of a time limit whose zero hour is teasingly unspecified. Some of the significant breakthroughs are to be expected but are always well reasoned and impeccably timed, and the small number of problematic barriers to progress and potential dangers are signposted at an early stage: in Leavitt's trancelike-reaction to red lights and her refusal to admit she may have a problem; in the over-reliance on the mechanical infallibility of a communication system; in the urgency of conversations about a nuclear powered self-destruct mechanism that will wipe out the facility if the virus leaks; and in the importance of knowing where the substations are to disarm it if necessary. From the moment Hall is handed the deactivation key and warned that some of the substations are not yet operational (seriously, this is the equipment they chose to fit last?) you know he will have to use it, but it still makes for a suitably nail-biting climax, one whose against-the-clock tension and whose dispassionate female voice delivering audible reminders of the time remaining play like a template for similarly themed scene in Ridley Scott's Alien. There are also a fair few twists in the second half that you just can't see coming but which always make scientific sense, adding to the feeling that if such a crisis occurred then this, on a technical level, is how it would play out. It's for good reason that the film was cited in a 2003 publication by the Infectious Diseases Society of America as "the most significant, scientifically accurate, and prototypic of all films of this genre" and that "it accurately details the appearance of a deadly agent, its impact, and the efforts at containing it, and, finally, the work-up on its identification and clarification on why certain persons are immune to it."*

The almost avant-garde electronic score by jazz musician and composer Gil Mellé proves effective in part because its usage is so carefully rationed, with key scenes playing without musical accompaniment, something that adds immeasurably to their factual feel. This air of realism is further enhanced by a cast in which there are no star faces, the lead parts instead played by talented actors who look like regular people rather than movie stars and whose down-to-earth performances make it easy to buy them as the experienced scientists they purport to be. Their technical banter always has an authentic ring and even their grouchier disagreements make sense here because the four have not formed a cohesive and trusting team over time but have been snatched from their homes and workplaces and forced to work together in difficult and sometimes frustrating circumstances.

Everything just comes together sublimely here, and while the film did divide critics a little on its release, the fact that it still feels so fresh is a testament to how ahead of the game it was. Some of the technology may have dated a little, but the science of the investigation still feels convincingly real and the process itself makes for utterly gripping drama. And although the novel that inspired it was published 50 years ago, the story it tells remains unsettlingly relevant at a time when the American Centre for Disease Control admits that at least one new infectious disease is being discovered every year, while existing viruses are developing new strains that make the fight to stay ahead of them one that is set to continue indefinitely and that humanity, for all its technological and scientific advancement, might one day still lose.

The result of a new restoration by Arrow Films from a 4K scan of the original camera negative, the 2.35:1 1080p transfer on this Blu-ray looks terrific, boasting a gorgeous contrast range that nails the black levels, has well-pitched highlights and loses none of the picture detail between the two. The detail is very crisp with no trace of digital enhancement and the colour is handsomely rendered, particularly the often vibrantly coloured walls of the higher levels at Wildfire and the luminous lighting effects and scans in some of the decontamination sequences. A very fine film grain is visible and there are no signs at all of dust or former damage. Lovely.

The Linear PCM 1.0 mono soundtrack is also in fine shape, with very clear rendition of dialogue and sound effects, despite the pre-Dolby absence of strong bass and a slight lack of finesse to the more extreme trebles of Gil Mellé's otherwise cleanly reproduced score.

Optional subtitles for the hearing impaired have been included.

Audio Commentary by Bryan Reesman

Entertainment journalist Bryan Reesman may laugh a little too often at his own comments and occasionally fall victim to the current trend for replacing the word "very" with "super" (sorry, that's everywhere on YouTube and drives me nuts), but he's really done his homework and clearly admires the hell out of the film, about which he has a lot to say and it's all worth hearing. He has information on several of the actors, director Robert Wise, author Michael Crichton, screenwriter Nelson Gidding, score composer Gil Mellé and special effects maestro Douglas Trumbull, tells a personal story that enabled him to relate to the experience of the elderly survivor (whose character name is Peter Jackson, I should note) and provides specifics about how the animal deaths were faked. It's also here that I learned there were a staggering 206 split-dioptre shots in the film, which surely has to be some sort of record. A useful and enjoyable extra.

A New Strain of Science Fiction (28:02)

Kim Newman is back in what I'm guessing is his study (he always seems to be filmed in the same location for these extras so is presumably comfortable talking there) and spreads his focus wider than the film itself to take a detailed and typically authoritative look at the evolution of the pandemic movie – or, as he calls them, decontamination suit movies – as well as briefly discussing the careers of Michael Crichton and Robert Wise and highlighting the strength of The Andromeda Strain, which he describes as "one of the great movies about what scientists are actually like."

Making the Film (30:08)

A 4:3 framed featurette directed by Laurent Bouzereau for a 2001 DVD release that includes interviews with Robert Wise, Nelson Gidding, Michael Crichton and Douglas Trumbull, plus extracts from the film's original featurette, presented by a fresh-faced Crichton and including some brief but welcome behind-the-scenes footage. Wise provides some interesting info on the making of the film and his approach to it, but it's Trumbull who had me riveted here with his explanation of how he produced what I would have sworn were computer-generated graphics using an optical slit-scan technique.

A Portrait of Michael Crichton (12:33)

Also directed by Bouzereau for the 2001 DVD release, this interview with Michael Crichton sees the author recall the early pull of being a writer and having to publish his first novels under a pseudonym to avoid not being taken seriously while at medical school, a plan that collapsed when he authored The Andromeda Strain under his real name and it became an unexpected bestseller. He talks about the importance of writing the book as if it were a true story and creating fake footnotes and bibliographical references to push the idea that it was a non-fiction work, and reveals that the main characters were all based on real scientists, one of whom realised and was not happy about it.

Cinescript Gallery

This is interesting. Included as a 192-page PDF file on the BD-ROM folder on the disc is what is described here as a ‘cinescript', which is effectively Nelson Gidding's screenplay but with the addition of detailed notes, diagrams and drawings on the proposed look of the film, as well as time schedule of events that take place within it. As ever, it's also interesting to see how the dialogue was altered in the journey from page to screen, and I was interested to see the female voice that provides a countdown in the film's climax described in the screenplay as "Seductive Voice." Aware that not everyone has a BD-ROM drive, Arrow has also made the entire document available as an on-disc extra to be viewed on screen, and has split it into three sections: Title page and preface; Shooting script; and Appendix.

Theatrical Trailer (3:18)

Introduced by director Robert Wise wearing the nuclear deactivation key and announced as "the story of the world's first space-age crisis," this trailer smartly compresses the events of the first third of the film, but includes way too much of the climax to be safely watched before the film itself. It ends with the warning, "No-one will be seated during the last 10 minutes." I should bloody well hope not.

TV Spots (1:50)

Three niftily edited TV promos whose 4:3 framing reminds us how much you miss when a scope print was cropped for TV back in the day.

Radio Spots (1:49)

Two radio spots that bring home the importance of the visuals when it comes to selling the film.

Image Gallery

This is divided into two sections. Production Stills includes 116 production photos, including some behind-the-scenes shots and one of a sequence involving a full body decontamination bath that didn't make the final cut. The quality varies, depending on the source and condition of the original materials, but the best look terrific. Poster and Video Art

Consists of 52 slides of posters, magazine ads, press kit pages and video/DVD covers.

Also included in the first pressing of the retail disc is an Illustrated Collector's Booklet featuring new writing on the film by Peter Tonguette and archive publicity materials, but this was not supplied for review.

The Andromeda Strain is one of those films that I just can't be dispassionately analytical about. It creeped me out as a teenager and frankly just seems to have gotten better every time I've seen it since and just blew me away on Arrow's Blu-ray. If you're already a fan of the film then this is the disc to own, for the excellent transfer and some enjoyable and informative special features, and if you've somehow never seen it and are a fan of the genre, then what are you waiting for? Highly recommended.

|