| |

“Ideas are like fish. If you want to catch little fish, you can stay in the shallow water. But if you want to catch the big fish, you’ve got to go deeper. Down deep, the fish are more powerful and more pure. They’re huge and abstract. And they’re very beautiful.” |

| |

David Lynch in Catching the Big Fish:

Meditation, Consciousness, and Creativity |

| |

On the first evening over rum drinks, having just heard sad news from England, I said to Noël,

‘It’s terrible – I’ve arrived at the age when all my friends are dying.’

‘Personally,’ said Coward. ‘I’m delighted if mine last through luncheon…’ |

| |

David Niven recalls an exchange with

Noël Coward in The Moon’s a Balloon |

When I first read that above quoted exchange in David Niven’s hugely entertaining autobiography, The Moon’s a Balloon, it had me giggling uncontrollably, in no small part because of the terribly upper crust manner in which Coward doubtless delivered that response to Niven’s comment. Now, as I thunder into my twilight years, the grim subtext that underscores that conversational snippet has become all too real. I’ve lost most of my family now, a few good friends, and even a former partner. It also proved unexpectedly sobering when the filmmakers, actors and musicians who were instrumental in shaping my younger self started dying – it felt and still feels almost as if part of my youth died with them, and their loss acts as an unwelcome reminder that my own time is running out at a seemingly increasing pace. Certain such deaths had a particular impact on me. The Clash’s Joe Strummer dying at 50 seemed outrageous at the time, but even that paled against the news that David Bowie had passed away. For some inexplicable and nonsensical reason, in my mind’s eye Bowie was someone who had been gifted with a degree of eternal youth and was thus going to outlast me by at least a century. And now we’ve lost David Lynch, a singular filmmaker and enthusiast for woodworking, cigarettes and coffee, and one of the few artists whose work had a genuinely life-changing impact on me.

I was at film school and in the process of seriously widening my film appreciation, having grown up on a diet of American and British mainstream titles that graced our local cinema and classic era Hollywood films that graced the weekly TV schedules. To that end, I’d joined the BFI and spent many happy hours discovering films that I was previously unaware of at London’s National Film Theatre. I also made weekly visits to the lovely little cinema located in the arts centre that was just a short train ride from the town in which I was studying. I remember that I was in one of the school’s editing rooms flicking through the latest copy of Films Illustrated when I was confronted by a monochrome still from a new independent American film, an image that frankly stopped me in my tracks. The review that accompanied it had me salivating – everything I had spent a couple of years completely failing to find a way to translate into a cinematic experience had apparently been achieved by this extraordinary new film. The work in question, of course, was Eraserhead, the debut feature of a certain David Lynch. It was a film that no UK distributor seemed even remotely interested in handling and it only became available for cinema viewing anywhere in the UK when London’s Scala cinema temporarily put its programme of delicious daily double-features on hold for a few weeks to exclusively screen it, pairing it with the 1976 Devo music short, In the Beginning was the End: The Truth About De-Evolution. If I really got into the impact the film had on me and my filmmaking ambitions, such as they were, we’d be here all night, and I’ve already covered the former in some detail in my review of the film’s DVD release here. I’m sure Camus will not remember this, but when he finally saw it and I asked him what he thought, he memorably replied, “It was like having my stomach eaten by worms.”

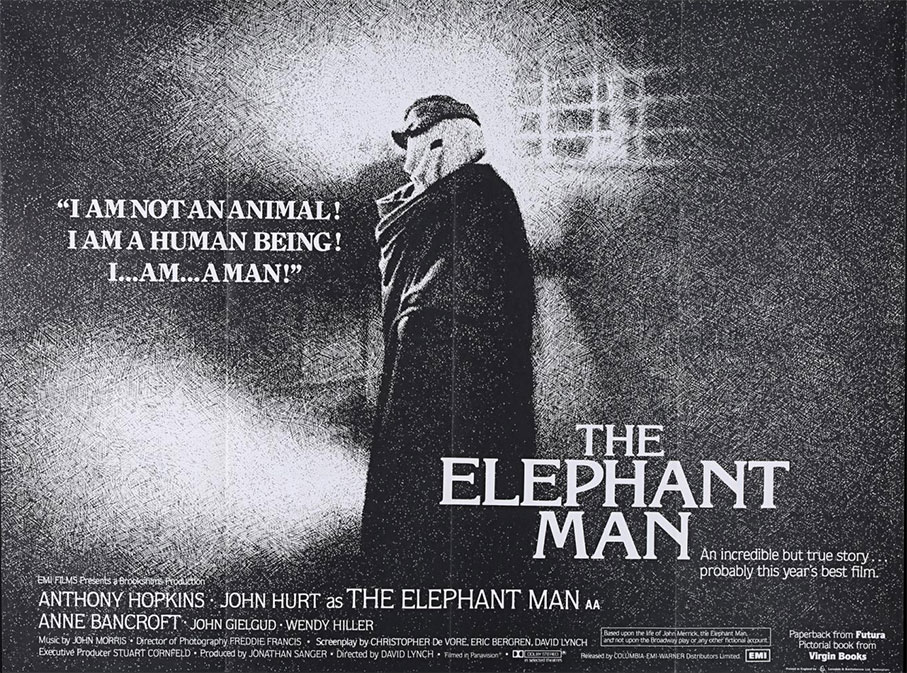

When Lynch landed the job of directing The Elephant Man, I was both surprised and excited, particularly when I purchased a book packed with production stills and behind-the-scenes photos, all of which were in radiant black-and-white. Before I got to see the film, I received a phone call from my closest friend at the time, who had never been exposed to Eraserhead but had already seen The Elephant Man due to his interest in the true-life story of Joseph Merrick. He was stunned and left an emotional wreck by the film and insisted that I rush to see it as quickly as I could. Rather than wait another week for it to screen at my local, I travelled to a nearby town and saw it there and spent the last five minutes in floods of tears that I did my best to hide from the sizeable number of people queuing in the lobby for the next screening. The detour I took to avoid walking straight through the busy lobby led me unexpectedly to where the cinema manager was standing. I told him how much I had loved the film and found that he was also a fan. “I’d love to get my hands on that,” I told him while pointing at the framed poster, to which he replied, “Drop by next week when the film has finished its run, and you can have it.” I could have kissed him. When I returned, however, he was out for the day, and the assistant manager knew nothing about his offer. I had a hell of a job convincing her to let me have what she was under the impression should not be given away, but I eventually wore her down and she handed it over. I still have it, and it’s in immaculate condition and one of the best (and, as it turns out, most valuable) posters in my eclectic collection.

As we lived some distance apart, the film became the main topic of discussion between my friend and I in the phone calls that followed, and when we met up a few weeks later, we went to see it again and were both again reduced to tears by the finale. With my friend so impressed by the work of a director he had not been previously aware of, I thought it might be the time to introduce him to Eraserhead. “Do you think you could handle an entire 90-minute film with the logic and tone and surrealism of the dream sequences in The Elephant Man?” I asked him. He believed that he could, little knowing what he was in for. So off we went to the Scala, where the film was this time paired with Tod Browning’s masterful Freaks (1932). When Eraserhead concluded, my friend fell to the floor and screamed, “HAS IT GONE AWAY YET?” Two hours later, we were back at his house, and he was sitting in his armchair, a wooden board on his lap, on which sat a large lump of clay that over the next three hours he fashioned into a remarkably accurate model of the Eraserhead baby.

I remember being bemused by the very idea that Lynch’s next film was to be an adaptation of Frank Herbert’s science fiction novel Dune, a book that I was never really able to get into and freely admit to never finishing. This was to be Lynch working with a studio-sized budget, huge sets, visual effects, and many prestigious actors to create a film whose grand scope was so divorced from the indie passion-project that was Eraserhead that I was initially uncertain enough to be hesitant about nipping to the cinema to see it. What gave me the push was a locally based friend who had rushed off to see it as soon as it hit local screens and was already keen to see it a second time, and he had a car. I should have had more faith. Yes, I know that the film has since been eclipsed by the first two chapters of the epic adaptation by Denis Villeneuve, but at the time, I was utterly captivated by Lynch’s version, for its poetic qualities, its surrealistic undertones, its fabulous production and costume design, and its top-notch cast. Despite my deep admiration for the Villeneuve version, I still have a real affection for Lynch’s film and annually revisit it, nowadays on Arrow’s 4K UHD disc.

A couple of years later, an article in Time Out had me fired up to see Lynch’s first colour film to hit the UK, Blue Velvet. By then, I’d moved some distance from the capital city but on the week of Blue Velvet’s release, a friend and I took a two-hour train journey to Central London in order to see it. The cinema was packed, and when we emerged after the screening, we headed to a nearby pub to try and come to terms with what we’d just seen. In retrospect, I just can’t remember what it was about the film that had left us unsure about how we felt about it. You see, a few weeks later I was back in London on work-related business and took the opportunity to see it again, and whatever issues I thought had the first time around dissolved into irrelevance. I emerged from the cinema this time with the rock-solid conviction that the film I had just seen was a bona fide masterpiece, a view that has not altered in the many years and multiple subsequent viewings on everything from criminally cropped VHS to its uneven but intermittently excellent Blu-ray transfer. I outlined my views on the film in detail when I reviewed two of its DVD releases back in 2004, which you can read here. I’m currently saving up for the Criterion UHD release, which frustratingly has only been released in the US and is not the cheapest of discs to import.

After Blue Velvet, the news that Lynch was working with co-writer Mark Frost to create a television series seemed too good to be true, and when it hit screens in America the buzz around it was so exciting that it had me climbing the walls in frustration that I couldn’t get to see it. You have to remember that this was back before streaming was the big conglomerate behemoth that it is today, where just about any new series is just yet another subscription fee away. What happened instead – and I’m still not sure why – was that the 94 minute pilot episode was extended to 116 minutes with additional, presumably specially shot material to transform what was intended as a narrative and character setting opening episode into a stand-alone film, complete with a story conclusion. The result was released in European countries on VHS, and this was my introduction to the cultural phenomenon that was Twin Peaks. And it blew my mind.

When the series itself finally arrived in the UK, I was thus already hooked and remained so even through the studio-enforced second series reveal and the various unexpected and delightfully strange directions in which the storyline subsequently went. This was genuinely groundbreaking television of the like I hadn’t seen since The Prisoner in which Lynch and Frost and their various talented collaborators took the familiar format of the TV soap opera and turned it upside-down and inside-out, transforming it into a horror-infused murder mystery with a strong surrealist leanings. The writing was superb, the direction impeccable, the characters instantly memorable and wonderfully played, and the tone had a genuinely dreamlike and often nightmarish quality. The mood enhanced no end by a superb score from composer Angelo Badalamenti, who had first worked with Lynch on Blue Velvet, which marked the start of a heavenly creative partnership that was to continue for many years to come. The series opened up new doors for television drama (it has been credited with paving the way for the now common practice of having a single story to play out over a whole series) and helped to shape the medium into the home for creative writing and direction that it has since become. As The Sopranos creator David Chase memorably stated, "Anybody making one-hour drama[s] today who says he wasn't influenced by David Lynch is lying."*

I remember a good friend of mine at the time describing Lynch’s next feature, Wild at Heart as “Twin Peaks on acid,” which even at the time seemed to be missing the point of what for me remains one of the great and truly passionate love stories of twentieth century cinema. Just as I think I initially wasn’t sure about Blue Velvet – perhaps for the simple reason that it wasn’t Eraserhead – my first response to Wild at Heart was a slight disappointment that it wasn’t another Blue Velvet, but once again a second viewing solidified it as the major achievement that it is, and it gave a perfectly cast Nicolas Cage and Laura Dern two of the very best roles of their respective careers, to say nothing of Willem Dafoe’s turn as the loathsomely creepy Bobby Peru. Despite its ever so slightly divisive Palme D’Or win at Cannes, when I reviewed the American DVD release of the film back in 2005 (which you can read here), I was still of the opinion that it was not quite top-drawer Lynch, but in the years since, the film has rocketed in my estimation, and on the day of Lynch’s passing, when I screened the opening fifteen minutes or so of every film of his in my collection, it was Wild at Heart that I ended up watching to the end.

Then, in 1992, Lynch, together with co-writer Robert Engels, returned to the world of Twin Peaks, this time with a theatrical feature enticingly titled, Twin Peaks: Fire Walk With Me. With the series having been cancelled at the end of season two, the expectation was that this would be a sequel that would wrap up all the storylines that were left teasingly hanging, expectations that were confounded when Lynch and Engels instead delivered a prequel that charted homecoming queen Laura Palmer’s descent into a hellscape that ultimately resulted in her murder. The result infuriated many series fans and was ruthlessly savaged by the vast majority of critics. I thought it was astonishing, and still to this day regard it as one of Lynch’s greatest achievements. It’s a traumatising, terrifying, heartbreaking tale of familial abuse and the destructive and ultimately self-destructive impact this can have on its victims, one whose deeply discomforting reality is infused with a nightmarish level of surrealistic horror to ultimately devastating effect. The acting from a top-notch cast is consistently excellent, but special mention has to go to Sheryl Lee, whose performance as Laura is nothing short of astounding and key to why the character’s downward spiral has me close to tears on every viewing. One of the few critics who championed the film on its release was Mark Kermode, and he has continued to do so since (check out his Kermode Uncut video about it here), describing it as Lynch’s masterpiece, and the film has since undergone a critical re-evaluation and is now widely recognised for the major work that it is. Shame it took so bloody long.

It's then that Lynch made what for me was his only real artistic stumble, though I have to admit I’m basing that statement on a single viewing over twenty years ago, and past experience suggests that I’ll see it in a different light should I get the chance to see it a second time. In 1992, the same year that Fire Walk With Me so enraged the critics, Lynch again teamed with Mark Frost to write a TV series whose pilot he would also direct, and I’m guessing that it’s one a fair few of you reading this have never seen and possibly never even heard of. The show was titled On Air and was a half-hour comedy series centred around the disastrous attempts to stage a live TV variety show in the 1950s. I’ll freely confess that I don’t remember much about it all these years later, except that it didn’t make me laugh, and for a comedy show, that’s a bit of a handicap. I gather that it really polarised audiences, and was hugely enjoyed and hated in equal measure, but clearly the network wasn’t happy as it was cancelled after just three shows had aired. I really need to see this one again.

I was far more receptive to the three-episode HBO series Hotel Room, which Lynch created with his friend Monty Montgomery in 1993, the first and third of which Lynch also directed. It gave him the chance to work with some of his former collaborators, with all three episodes scored by Angelo Badalamenti and with lead roles played Harry Dean Stanton, Freddie Jones, Crispin Glover and Alicia Witt. In addition, both of the Lynch directed episodes were written by Barry Gifford, the author of the novel on which Wild at Heart was based and with whom he would soon work again. With each episode set in a different decade and largely confined to room 603 in an unnamed New York hotel, these are effectively dialogue-driven one-act plays that shine as showcases for Gifford’s writing and the sublimely pitched performances of the small cast. In the first episode, the 1969-set Tricks, a man named Moe (Harry Dean Stanton) arrives at the hotel room with sex worker Darlene (Glenne Headly), only for their planned assignation to be interrupted by the arrival of Lou (Freddie Jones), whose relationship to Moe is never fully specified. What subsequently unfolds has an almost Pinteresque quality at times, with even just a whiff of Samuel Beckett, with Stanton on superb form right up to the final semi-surrealistic twist. The final and longest episode, Blackout, is set in 1936 during a thunderstorm-induced power cut, as a man named Danny (Crispin Glover) arrives back at room 603 with some Chinese food to share with his emotionally damaged wife Diane (Alicia Witt). The blackout of the title allows Lynch to plunge the room into darkness and focus of the candlelit faces of two leads as Danny does his best to reassure Diane, who has lost the ability to differentiate delusions from reality. It’s this condition that has brought them to New York in the first place for an appointment with a specialist doctor the following day, and as the two interact, the likely cause of Diane’s mental deterioration slowly becomes clear. Both episodes make for compelling viewing, and are moodily shot by Lebanese cinematographer Peter Deming – with whom Lynch would also work on his next two features – and boast atmospheric sound design by Lynch himself.

Another four years would pass before Lynch returned to feature film directing, co-writing the script with Barry Gifford and delivering what for me remains one of his most hauntingly brilliant evocations of the experience of nightmares since Eraserhead. The sense of dread in that’s created from the off and that builds to a crescendo during the first half of Lost Highway is like nothing I’d previously experienced, and it still gets right under my skin umpteen viewings later. The sequence in which Bill Pullman’s Fred Madison is confronted by Robert Blake’s Mystery Man at a party is one of the most gorgeously unsettling in all of Lynch’s oeuvre, and the line about Fred hating video cameras because “I like to remember things my own way… how I remembered them, not necessarily the way they happened” plays now like a chilling prediction of the post-truth pit into which societies worldwide are suicidally plunging. On my first viewing, I was completely thrown by the mid-film switch, but there’s a discomforting, almost dream-like logic to what subsequently unfolds and how it twists itself into a narrative moebius strip. And, of course, we have Robert Loggia, who channels his frustration at not landing the role of Frank Booth in Blue Velvet and his rage at being kept waiting so long by Lynch for that audition into a scene in which he brutally lectures a tailgating driver, a speech that you can’t help thinking came from Lynch’s heart and personal experience. We screened the film to a full house at the cinema-based film society I used to co-run, and I was genuinely nervous when I saw a friend of mine who had hated Eraserhead with a passion approaching me after the screening, presumably to ball me out for programming another reason for him to hate on David Lynch. To my surprise and delight, the first word out of his mouth was “Astonishing!” which was followed by the anguished question, “What the hell was in the corner of that room?” You’d need to see the film to understand why that mystery so rattled him. That said, my favourite evaluation of the film came at the conclusion of Kim Newman’s excellent Sight & Sound review, when he stated, “After 100 years of cinema, it is still possible to make a truly terrifying picture.”

The sheer boldness of the structural experimentation of Lost Highway left us completely unprepared for what Lynch delivered next. The 1999 The Straight Story is a touching, heartwarming and deeply moving tale of frail 73-year-old retired Iowa farmer and widower Alvin Straight, who learns that his estranged older brother is critically ill and becomes determined to make the 240-mile journey to Mount Zion, Wisconsin to make peace with him. The only problem is that Alvin does not have a driving licence, and with his eyesight failing he is unlikely to be granted one, so he decides to make the journey on a 1966 John Deere lawn tractor with a sizeable trailer in tow. While the surface oddness of this decision may read very much like a Lynch invention, the script, by John Roach and Lynch’s long-time partner and collaborator Mary Sweeney, was based on a true story whose principal elements are faithfully recreated here. The real-life Alvin Straight was 73 and suffering from several ailments, including diabetes and emphysema, and on hearing that his older brother had suffered a stroke, he drove a John Deere tractor mower 240 miles towing a trailer loaded with fuel, supplies and camping gear for the journey. Alvin’s journey in the film even follows the exact same route taken by Straight, and was shot in chronological order to more easily facilitate this.

Whilst several commentators have found second meaning in the title as a pointer to what they saw as Lynch’s first truly mainstream and unashamedly audience-friendly drama, Lynch himself has described it as his most experimental movie, quite possibly because it was so outside of his normal cinematic comfort zone. As always with Lynch, the acting is impeccable, with a gorgeous, Oscar-nominated central performance from former stuntman turned character actor Richard Farnsworth, who was terminally ill with metastatic prostate cancer when he took the part and who tragically took his own life the following year. A shout out, too, to Sissy Spacek for her nuanced portrayal of Alvin’s emotionally damaged daughter Rose, a casting that loops all the way back to Eraserhead, in which Spacek’s art director husband Jack Fisk played The Man in the Planet in the film’s opening and closing scenes, while Spacek herself is thanked in the film’s closing credits.

The same year that The Straight Story hit cinemas, Lynch returned to television with a 90-minute pilot for a new series for the ABC television network, but when he screened a rough cut to a single and apparently distracted network representative, the man hated what he saw and the series was immediately cancelled and the pilot never screened. But thanks to the efforts of Lynch’s friend, Pierre Edelman, a deal with French distributor Canal+ was eventually struck to provide Lynch with the funds he needed to transform the pilot episode into a theatrical feature. The result was the 2001 Mulholland Drive, which was released to widespread acclaim and landed Lynch his second Palme D’Or win at Cannes (which he shared this time with the Coen brothers’ The Man Who Wasn’t There). It has since gone on to be championed by many as his greatest work, and even came in at number 28 in a 2022 Sight and Sound poll of ‘The Greatest Films of All Time’ (a meaningless phrase when you consider that the term ‘all time’ would include the future) and topped a 2016 list of 100 Greatest Films of the 21st Century (another hyperbolic title that should have included the words ‘so far’).

A satire on Hollywood dressed in the seductive clothing of a surrealistic neo-noir mystery thriller, one that reworks the narrative switcheroo from Lost Highway to very different effect, Mulholland Drive sees Lynch once again firing on all arthouse cylinders and again extracting superb performances from his lead actors, in this case Naomi Watts and Laura Harring. It’s a captivating and haunting work with electrifying moments that peak in Rebekah Del Rio's hyperemotional Spanish language a-cappella rendition of Ropy Orbison’s Crying, a sequence that has the two leads and half the viewing audience in tears. As we did with every Lynch film from Lost Highway onwards, we screened a 35mm print of the film to a packed house, and there was much discussion about the film in the handily adjacent wine bar afterwards, all of it positive. Yet here’s the thing, and I’m opening myself up for a few judgemental brickbats here, but much as I love Mulholland Drive, I still prefer Lynch’s previous experimental noir, Lost Highway. Do I think it’s a better film? Not particularly, but the simple fact is that Lost Highway still speaks to me on what always feels like a personal level. Like Blue Velvet before it, it took a couple of viewings for me to really connect with what makes Mulholland Drive such an extraordinary film, but Lost Highway burrowed into my brain on the first viewing and took up residence there and to this day shows no sign of leaving. It’s a personal thing, and I’m just glad we have both films, but I still ache for the Mulholland Dr. series that could have been and that we will never now get to see.

It would be another four years before Lynch would direct what would turn out to be his final feature, during which time he discovered and fell in love with digital video, praising its immediacy, its low cost, its portability, and the fact that he could create animated sequences on his home computer on Adobe After Effects. Consumer HD was still a few years away, and Lynch’s camera of choice at the time was the prosumer DV-CAM favourite the Sony PD150, which Lynch had already used to create a whole series of experimental shorts that he showcased on his website DavidLynch.com (we covered some of them when they were released on DVD here). Fans of the director’s work should also hunt out his early shot-on-film shorts Six Men getting Sick (1967) The Alphabet (1969) and The Grandmother (1970), the last of which has the mood and tone of Eraserhead but was shot in sometimes vivid colour.

Then, in 2006, Lynch took this digital experimentation to another level with Inland Empire, a three-hour surrealistic psychological thriller that was shot entirely on the PD150 by Lynch himself. It reunited Lynch with former collaborators Laura Dern, Justin Leroux, Harry Dean Stanton, Daine Ladd, Grace Zabriskie and Naomi Watts (who plays a rabbit in extracts from one of Lynch’s experimental shorts), and featured Jeremy Irons, Julia Ormond, Mary Steenburgen, William H. Macy, Nastassja Kinski and others in prominent and supporting roles. The film saw Lynch revisiting and reworking themes from his previous features, but freed from the constraints that come with an even moderately budgeted 35mm production, he seemed more willing than ever to experiment with form, ideas and even approach, shooting without a completed script over the course of over three years in Poland, France and the US, and editing the footage on Final Cut Pro in his office for six months after the shooting had wrapped. Dern plays fading Hollywood star Nikki Grace, who at the start of the film is waiting to see if she has landed the lead role in a romantic drama titled On High in Blue Tomorrows, which a strange woman who visits her accurately predicts she will get. She does, but during the rehearsal discovers that the film is a remake of a Polish production that was left unfinished after its two lead actors were murdered, and the more Nikki becomes invested in her part, the harder it becomes for her to differentiate between the film and reality.

For some, Inland Empire remains Lynch’s most impenetrable film, for others his most self-indulgent, whilst for one friend of mine it was the film’s aesthetic that he couldn’t get on board with. As a fan of rich and visually sumptuous 35mm visuals of Lynch’s previous work, he found the standard definition digital video look of Inland Empire distractingly ugly. I do get where these naysayers are coming from, and if you share their complaints, I’m not going arrogantly claim that you are wrong, just that on these points we’re going to have to agree to differ. Yes, I struggled with the film’s fragmented narrative development on my first viewing but was no more mystified than I had been when first exposed to Lost Highway or Mulholland Drive, and every bit as mesmerised. And while I’m also a huge fan of the look of previous shot-on-film Lynch works, the film’s low-band digital aesthetic – which includes a few shots where the focus is just a whisper shy of sharp – feels like a natural extension of his experimental shorts. It also now has a particular place in film history as one of only a handful of features that were shot on mini-DV, a digital format whose window as a production format opened and closed within a few short years, something I discussed in a blog back in June of 2022.

Having stated that he was done with film and that he planned to work exclusively with digital from this point on, Lynch had me wondering just what sort of film he would deliver next, only to learn, to my dismay, that he was effectively retiring from filmmaking to concentrate on painting and drawing. Well, almost. In 2011, he really caught me out by directing a livestreamed concert by Duran Duran, one of the new romantic bands that were the bane of my post-punk younger days. As an actor, Lynch parodied his own image by playing himself in an episode of Seth McFarlane’s animated series Family Guy, became a regular as Gus the Bartender in its spin-off series, The Cleveland Show, and guested as no-nonsense talent agent Jack Dahl in Louis C.K.’s comedy-drama series, Louie. He had also by this point begun collaborating on music projects with his regular score composer Angelo Badalamenti, and over the years also worked with singers Julee Cruise, Jocelyn Montgomery and Chrystabell, and released the albums BlueBob (2001), Crazy Clown Time (2011), The Big Dream (2013), Thought Gang (a collaboration with Badalamenti) and Cellophane Memories (2024). And yes, as a Lynch fan, I have them all.

But I still ached for just one more Lynch movie, and given his stated commitment to digital and the high quality now offered by even low cost HD cameras, the conditions were surely as close to perfect for him as they had ever been. A glimmer of hope came in the special features on the glorious Paramount Blu-ray box set of Twin Peaks, where Lynch chatted with key members of the series’ cast, and they all expressed the desire to work together again. Could it possibly happen? Oh yes. It started back before Twitter became a cesspool of right-wing bigotry and misinformation, when Lynch tweeted the line, “Dear Twitter friends: That gum you like is going to come back in style!” This was followed three days later by official confirmation from Showtime that Twin Peaks was soon to be returning, that Lynch and Mark Frost would be writing and executive producing, and that Lynch would be directing every episode. I was not the only one excited by this news, but in the UK it was screened exclusively on Sky Atlantic, and there was no way on earth I was going to give money to an organisation even partially owned by the malevolent mummy Rupert Murdoch (typically, about a year later he sold his share of the company to Comcast), and beyond that, taking out a subscription just to watch a single show was just not feasible on my limited budget. It’s the same reason I’ve still not been able to view a single episode of Shōgun, despite my aching desire to see it and repeated pleas for me to access it from my partner.

So I had to wait, but that wait absolutely proved worth it, and then some. I’d love to know more about the people at Showtime who decided to fund the series and give Lynch and Frost full creative control, and how they reacted when they saw what was delivered. If the first series of the original Twin Peaks was a televisual game-changer (and it was), what became known as Twin Peaks: The Return felt genuinely revolutionary, an uncompromising collision of drama and avant-garde experimentation that works sublimely both as a sequel to the original series and a full-blown surrealistic rethink of the world of Twin Peaks. Whole scenes played like live action interpretations of Lynch’s semi-abstract paintings, with the rule-breaking peaking in episode 8, where the drama is effectively paused for a lengthy and mind-blowing movie installation piece about the dropping of the first atomic bomb test. When Twin Peaks first appeared, there was nothing on TV like it, and it proved to be a similar story for Twin Peaks: The Return, but while the influence of the original series can be widely felt today, as a slice of artistic television narrative, The Return currently has no peers and no imitators.

Following this sensory overload, I had high hopes that Lynch’s return to directing would result in a new Lynch directed feature, but this was not to be. Having reteamed with Mark Frost to deliver close to 18 hours of highly cinematic and mind-bending television, Lynch then returned to creating and even starring in experimental shorts. He played a detective interrogating a monkey in his 2017 What Would Jack Do?; set the image of an ant-covered piece of decaying cheese to two tracks from the Thought Gang album in Ant Head (2018); delivered an animated horror tale in which a hole is created in the world through which a dark force passes in Fire (2020); observed a bug’s failed attempt to climb an earth wall in The Story of a Small Bug (2020); animated and voiced the mouth of a severed head as it tells its mother that it’s not going fishing in The Adventures of Alan R. (2020); and this is just a sampling. He directed music videos for Donavan and Chrystabell, turned the camera on himself for 18 two-minute episodes of a series titled What is David Working on Today? (2020-2022), and famously delivered 152 daily and rarely varying Weather Reports (2005-2021), as well as 16 episodes of Today’s Number Is… (2020), where he simply picked a random number from a jar in the manner of a lottery or bingo caller. He became a vocal advocate of transcendental meditation, something I can sadly never see myself being able to practice, in part because the only way to shut my overactive brain down is to make myself tired enough to fall straight to sleep. Yet for all this, his most widely seen swansong was not a work that he created but his performance in Steven Spielberg’s acclaimed The Fabelmans, where he played director John Ford in a short but memorable scene that was apparently a word-for-word recreation of Spielberg’s own youthful encounter with this legendary director. It’s a lovely turn, but if we talking Lynch performances to remember him by, I still favour his role as Harry Dean Stanton’s tortoise-owning friend Howard in John Carroll Lynch’s delightful and deeply touching Lucky (2017).

Now Lynch is gone, a victim of emphysema brought on by his lifelong addition to cigarette smoking, which led to a cardiac arrest after he was evacuated to his daughter Jennifer’s house due to the threat to his Los Angeles home posed by the California wildfires. I do regret never having had the chance to interview him or even ask him a quick question, and I’m going to miss him just being there and being David Lynch, because there really is no-one else quite like him, and certainly no-one making films or TV in his distinctive manner. His uniqueness can be gauged by the fact that his name has joined a specific filmmaking pantheon and become an adjective, with the term Lynchian used to describe films or scenes that have the sort of dark dreamlike quality that seemed to just come naturally to Lynch. He was the American surrealist, a true artist who worked in a medium where art often finds itself in conflict with commerce, and yet somehow he was able to deliver a whole string of cinematic and televisual works without seriously compromising his vision.

For me, however, my relationship with Lynch’s work has always felt more personal than even a sincere appreciation of his art and his craft and his strengths as a filmmaker. Eraserhead spoke to me on a level that only Luis Buñuel and Salvador Dali’s 1928 surrealist masterpiece Un Chien Andalou had before. Watching it, I felt as if Lynch had been burrowing around in my head as I dreamt at night and had transformed what he had found into images and sounds that evoked the experience of having a dream or a nightmare more vividly than anything I’d experienced in any medium before. It’s an element crucial of almost every film that he subsequently made, whether overtly visible or bubbling beneath the surface, while his portrayal of the strange and illogical as normal and everyday characteristics of a society that is never quite what it initially seems is the cinematic essence of the Comte de Lautréamont quote that became the mantra of the Surrealist movement, “the chance juxtaposition of a sewing machine and an umbrella on a dissecting table.” His films both inspired and haunted me, and the strength and purity of his vision, coupled with his gosh-darn-it “Jimmy Stewart from Mars”** persona, made him one of the very few filmmakers whose every project in every medium I eagerly sought out. I treasure the films and TV that he gifted us with, not just because of their artistic and entertainment value, but because the strong connection I quickly developed with them made it feel as if he was making them specifically for me. As film devotees, I’m sure we all have at least one filmmaker who was able to do that, a visionary who created films that you didn’t realise you desperately needed until you saw them. For me that was, and at this late stage in my life probably always will be, David Lynch. He was truly the man from another place.

** A sublime description of Lynch delivered by comedy legend and The Elephant Man executive producer Mel Brooks.

|