We tend to have a fondness for courtroom dramas here. The best ones usually pit an underdog against seemingly impossible odds which he or she (and let's face it, it's usually a he) eventually triumphs over through a combination of intelligent reasoning, good fortune, and a morally righteous standpoint. As Slarek's selections demonstrate, however, that's not always the case, and sometimes the strength of a great courtroom scene comes from reminding us of the power that those in authority can unjustly wield over others. As ever this is not designed to be a definitive list, just ten personal favourites (or rather nine and a guilty pleasure) for you to disagree with.

1. Inherit The Wind (Stanley Kramer, 1960)

The Scopes 'Monkey Trial' was a famous event in American law in 1925. Still in place in certain States was a law forbidding the teaching of Darwin's Theory of Evolution (can you actually believe that?) and when a substitute teacher tried to educate his class with factual truth, he was hauled up before the bar and taken to trial. Now, if there's one thing that's easy to pick on, it's the past but hell, religion's hold over people of science and reason was made law out of what else but fear. What happened to 'the truth shall set you free...'? (John, 8/32). Ironies just spew out of the Good Book, don't they? The 1960 dramatisation of the trial presents Spencer Tracy as the big shot Chicago lawyer who comes down south to argue the case of reason. It's also very unusual to see a non-singing and non-dancing Gene Kelly, a charming actor not too often given the chance to strut his Thespian stuff. There's also a wide-eyed Dick York as the accused, Samantha's first husband in the TV show, Bewitched. The point of view of the film is definitely skewed on the side of the evolutionists (the religious enthusiasm in the film comes across as entertainment for credulous half-wits). The head of the village, the smug Matthew Brady (Frederic March) turns the trial into a test of faith and the court scenes dotted throughout are all compelling but it's the penultimate court scene, the duel between smug faith-head and reasonable man of intelligence that sets fire to this drama. It still amazes me in the extreme that religious ideas hold so many in such a powerful grip, a power that can not only be nullified by reason but can also be sent scuttling away back to the dark past where it really belongs (and it was all bullshit then too but not out loud...).

DVD review >>

2. Duck Soup (Leo McCarey 1933)

Word play, as some of our visitors may have noticed on our review headers, looms large in enticing the reader to go further. These are all our own work, as we can't afford sub-editors. Such playful language is seldom celebrated in cinema probably because movies are a visual medium. But, in one of the funniest movies ever made, a true Marx Brothers classic, the court scene still stands up. In Duck Soup, Rufus T. Firefly (Groucho) has to oversee the trial of Chicolini (guess who). Charles B. Middleton, who played Ming The Merciless in the original Flash Gordon TV series, is the prosecuting counsel. Let's just say that every Chico-ism is a wordplay of one sort or another and the one that shines bright is Groucho's "Here, he sits alone, an abject figure..." to which Chico responds "I abject!" Groucho gears up next with, "Here he sits, alone, a pitiable object... Let's see you get out of that one." There is no nail-biting tension provoked by new evidence revealed and counter arguments do not flit hither and thither (there's a Third Man joke here somewhere) but when Chico starts with asking "What has a trunk but no key..." the answer always makes me smile. A truly terrible pun makes my own partner groan with a puzzled annoyance. "It's not funny!" she says. I object. I know this High 5 is not really about how funny a scene is but as a truly memorable court scene, it gets a nod.

3. A Matter Of Life And Death (The Archers, 1946)

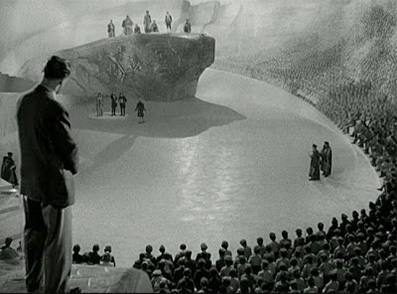

I wasn't going to include movies I'd already reviewed. Boomerang has a superb court scene but it's too fresh. I wanted to cast my net a little wider, give other movies a mention. Well, I have reviewed AMOLAD but still, how can you not love a court scene that goes on for the last 35 minutes of the movie and debates the celestial or earthly fate of a man in love. The choices are stark; David Niven (Peter Carter) should have lost his life leaping from his stricken aircraft without a parachute... Is he allowed to stay on Earth because he's fallen in love or taken back up the many steps to Heaven? Sorry, but this one is brilliant (ahem) on so many levels. There are stunning moments of visual invention that put modern filmmaking to shame but my real thrill throughout the scene is watching how artfully the late Dr. Reeves (Roger Livesey) steers the court to see things from his point of view. Also remember that the drama is playing out in four different places, the two metaphysical realms of the presented 'Heaven' and what may be real in the mind of Peter Carter himself. There's plain old planet Earth and a time-stopped Earth and all four are dropped into and out of and there is never a moment when we're unclear of the narrative. It's the moment when Dr. Reeves has the jury changed because of a perceived prejudice - a scene which always gets me - and this simple act says so much about America in a positive way. Using the conventions of the trial and courtroom procedure, a bold point is made which I hope we can all be sympathetic to - "This is a court of justice, not law..." Here, here.

DVD review >>

4. A Man For All Seasons (Fred Zinnemann, 1966)

Before he was bitten in half and swallowed by Bruce nine years later, Robert Shaw played an alluring and lusty King Henry VIII in the film version of Robert Bolt's play, A Man For All Seasons. Thomas More is a man with a conscience problem. In the crudest terms, a man is hot for a woman not his wife. His religion will not allow him to divorce. But the 'he' in question is in fact the King of England and enjoys some power as nominal Head of the Church. So Henry changes the law but one of his trusted advisors passionately believes that God comes before King and earns some displeasure at his stubborn obduracy in the face of smooth relations with the Pope and the entire structure of the Catholic Church. That was the 16th century and religion held societies like gnats in amber. Social enlightenment and progress was hampered by adherence to faith. Although this trusted advisor (Sir Thomas More) was a staunch God-Squadder, he has to be admired (like Socrates) for his refusal to bend to the political will thereby making a mockery of his faith and yes, no surprise, this cost him his head. Paul Scofield plays More as a benign realist who is only ever given to rash, self-damning pronouncements after he knows the court wants and will have his life. It's that scene that is so electrifying despite the errant silliness of his pronouncements - 'facts' about religious ideas that cannot be seen as factual by anyone of any intelligence. All throughout the movie, the quiet, self-effacing man of good conscience is asked to sway and bend but he never wavers. When the gloves come off, the only modern precedent I can recall is the trial of Tyrion Lannister in Game Of Thrones when Tyrion knows his fate is sealed, he lets fly, both barrels. More speaks his mind after having been royally shafted by Thomas Cromwell (Leo McKern) and Sir Richard Rich (John Hurt). As More says to Rich as he withdraws (noting the bribe of power over the principality of Wales given to him for perjuring himself...) "It profits a man nothing to give his soul for the whole world, but for Wales..." How damning is that? Especially if you're Welsh.

5. A Few Good Men (Rob Reiner, 1992)

This one's the guilty pleasure and it's as mainstream as it gets. I'm not a great fan of Tom Cruise but I admire the man's work ethic and have only heard positive stories from people I know who've worked with him. The Scientology stuff is as ridiculous as any religion but to see him go up against Jack Nicholson gave me a real frisson. Some things help. How about a script written by Aaron (West Wing, The Social Network) Sorkin? Director Rob Reiner wasn't exactly an untested and unproven director. And this was the decade when Demi Moore was driving studios insane with her diva demands (three years later, she was the highest paid actress in Hollywood) but her work in the movie is exemplary. Let's also nod to the doctor giving expert testimony, a straight-laced chap who, with a demented wig made us all chuckle in This Is Spinal Tap (cap doffed to Christopher Guest). But it's Cruise's hotshot lawyer living up to a father's reputation going after a vain and arrogant man where the meat and potatoes are. Everything hinges on whether Colonel Jessup (Nicholson) gave an order or not and Cruise feels "...that he wants to say it, that he made a command decision and that's the end of it." Nicholson's initial confidence and swagger are wonderfully deflated and Nicholson gives us a glimpse of his own career-past and how good an actor he was until he started playing 'Jack' on autopilot. Recognising and sometimes breaking through the thin line between control and chaos is something Nicholson is extremely good at. De Niro does another similar courtroom meltdown in The Untouchables (De Palma). This scene, of course, is where the now clichéd "You can't handle the truth!" came from. And so the powerful and the unassailable are brought low by simple justice. You have to love the courtroom drama.

The Verdict (Sidney Lumet, 1982)

Quite possibly my all-time favourite courtroom drama, The Verdict is one of director Sidney Lumet's most downbeat but immaculately crafted films, a compelling character study wedded to a gripping legal procedural. In one of the finest performances of his distinguished career, Paul Newman plays Frank Galvin, a once respected Boston lawyer whose marriage has collapsed and whose career has been reduced to ambulance chasing. Oh, and he's also a depressive alcoholic. When he lands a medical malpractice suit that the plaintiffs are willing to settle out of court, he decides instead to take it to trial in the hope of seeing the guilty punished and securing a more substantial settlement for his clients. This pits him against a powerful and experienced legal team led by legal bigwig Ed Concannon (a superb James Mason) and he soon finds himself hopelessly out of his depth. Utterly gripping from the start in that unique way that Lumet's finest films tend to be, it's a frequently punishing ride, a David and Goliath story in which David's slingshot is broken and his senses have been dulled by drink and failure. Even a longed-for and electrifying and unexpected moment of victory is later clouded by an overriding sense of failure. Sombre but brilliant drama.

Witness for the Prosecution (Billy Wilder, 1957)

By their very nature, the plots of courtroom dramas tend to have their fair share of twists – the surprise witness, the newly discovered evidence, the lucky break that turns the tide in favour of the defendant. But when your legal drama is sourced from a novel by Agatha Christie, you're talking twists of a whole different calibre, including an ending that the audience was requested not to reveal. My lips are sealed. In a performance that I have no problem categorising as glorious, Charles Laughton plays Sir Wilfred Robarts, a celebrated barrister famed for taking seemingly hopeless cases returning to work against medical advice following a heart attack. Here he is representing down-on-his luck war veteran Leonard Vole (Tyrone Power), who is accused of murdering a wealthy widow, out of whose will he did rather well. A delight from start to finish, Laughton is at his finest when cross-examining witnesses (his "chronic and habitual liar!" assault on Marlene Dietrich's icy cool Christine Vole is a memorable highlight – watch it here), or when engaged in a cat-and-mouse battle to hide liquor and cigars from his cheerfully bossy nurse, delightfully played by Laughton's real-world wife, Elsa Lanchester.

Blu-ray review >>

Paths of Glory (Stanley Kubrick, 1957)

In the WWI French trenches after the failure of an impossible battlefield charge, the officious and self-important General Mireau (an extraordinary turn from George Macready) orders that three men be selected at random and court-marshalled for cowardice as an example to the troops. Their unit commander Colonel Dax (Kirk Douglas – utterly superb) has the unenviable job of defending them, unenviable because the court in question is as biased and stacked against him as the one chaired by General Melchett against Edmund Blackadder in Blackadder Goes Forth. There's an overpowering sense of foregone conclusion about the whole affair, and the sense of helplessness when fighting those in positions of power is sometimes stomach-churning. Far and away the most emotionally punishing film in Kubrick's oeuvre – the small victories are there, but even they have a bitter aftertaste and ultimately fail to alter the wretched status quo.

Blu-ray review >>

Breaker Morant (Bruce Beresford, 1980)

While the trail may be only a small component of Paths of Glory's portrait of military injustice, it's the key component of Bruce Beresford's beautifully handled wartime courtroom drama. The true story of the court martial of three Australian soldiers accused of killing prisoners and a German missionary during the Boer war, it draws much of its courtroom dialogue from actual transcripts. The trial itself makes for genuinely electrifying drama, with the sterling progress made by inexperienced defence council Major Thomas repeatedly cut off at the knees by the sort of intransigence that makes it clear that there's a hidden agenda here. Terrific performances by Jack Thompson as Major Thomas and Bryan Brown as defiant defendant Peter Handcock, but stealing every scene he's in by a head is Edward Woodward as the titular Morant, notably in his memorable "Rule 303" speech (watch here).

DVD review >>

My Cousin Vinny (Jonathan Lynn, 1992)

OK, before I'm asked to hand in my cineaste membership card, I should explain my last selection. My fifth film was originally Inherit the Wind, which I absolutely adore, but Camus's list arrived before I'd written a word about it and he had, as they say, taken the words from my mouth. So I thought I'd choose another. I'd considered the Star Trek: The Next Generation episode, The Measure of a Man, a superbly written and performed examination of what defines us a sentient beings (you can watch Patrick Stewart in brilliant full flow here). But given the inclusion of Skin of Evil on my previous list, I was a tad apprehensive about including another episode of the same series here. I also nearly included the trial scene from William A. Wellman's wonderful Roxie Hart, which I remember being hilarious, but it's so long since I last saw it that I can't write about it with authority. So I decided, just for the fun of it, to go with a guilty pleasure instead. I'm not going to make a case for My Cousin Vinny as a great film. I'm not sure it's even a particularly good one. It's peppered with comedy stereotypes, its humour is sometimes obvious and it presses all the expected buttons in its tale of an ill-prepared but street-smart outsider holding his own against a system that dislikes him from the off. But there's still something about it that puts a smile on my face each time I see it. I've a particularly fondness for Fred Gwynn's humourless horse-faced judge, but in the end it's Joe Pesci – who runs with the role of Brooklyn-born lawyer who is hauled to Alabama to defend his young cousin on a murder charge – who proves the key draw here. And it's hard not to have a serious soft spot for a movie in which the defence council's response to a detailed and aggressive opening prosecution statement is simply, "Everything that guy just said is bullshit. Thank you." |