| DANCING ON THE EDGE OF A VOLCANO |

|

In 2014, at the government-owned Port of Beirut in Lebanon, a consignment of 2,750 tonnes of ammonium nitrate was moved into a warehouse after the ship onto which it had previously been loaded was pronounced unseaworthy. Despite repeated warnings of the danger of storing this material in what was deemed unsuitable climatic conditions, no action was taken to remove or relocate it. At 5.45pm on 4 August 2020, a fire broke out in the warehouse, and 20 minutes later a stash of fireworks being stored there exploded, sending a large and dark plume of smoke into the air. Approximately 35 seconds later, the ammonium nitrate ignited, triggering an explosion so powerful that it was felt over 200 kilometres away, and is estimated to be one of the largest non-nuclear explosions ever recorded. The impact on the city was devastating, blowing in windows, taking out apartment walls, completely destroying some buildings, and seriously damaging countless others over a distance of several kilometres, ultimately killing 218 people and injuring over 7,000 more. And this at a time when Lebanon was in a state of financial crisis and the whole world was in the midst of the Covid pandemic.1 Imagine being smack bang in the middle of that.

For Lebanese filmmaker Mounia Akl and her production team, no such leap of the imagination was required, as they were located dangerously close to the port, working on pre-production for Akl’s planned first solo feature, when the nitrate exploded. In the aftermath, Akl’s regular filmmaking partner, Cyril Aris, picked up a camera and began chronicling the potentially bumpy path the film might now have to walk to even go into production. And there’s no footage of the explosion itself here (you’ll find plenty of genuinely startling recordings of the event online, posted by people who were already pointing their phones at the smoke from the far smaller first explosion), only a black screen accompanied by the increasingly anguished cries of those affected and snippets of handheld footage taken in the devastated streets.

We’re introduced to various members of production team as they say their first words on camera, each of them identified by name and their role on Akl’s film, and there are just too many for my feverish notetaking to keep complete track of. A few of them, however, make an immediate impact. From the moment we first meet him, easy-going cinematographer Joe Saade proves instantly likeable, remaining quietly upbeat even though his apartment took the full impact of the blast, leaving him injured and blinded in one eye. “Ironic for a cinematographer,” he dryly notes, commenting on his blown-out windows, “On the bright side, there’s a breeze now. I didn’t have that luxury before.” And at a time when drone shots have become the most visually repetitive trick in the modern filmmaker’s book, Aris puts one to such good use here, as the camera retreats back through Saade’s apartment and out through its now-destroyed rear wall to reveal the full extent of the damage, and then drifts sideways to show that his immediate neighbour’s home in a similar state. It’s the first of several drone shots that have a kind of terrible beauty to them, akin in some ways to the aerial footage of burning Kuwaiti oil fields in Werner Herzog’s extraordinary 1992 documentary, Lessons of Darkness.

I took an instant liking to producer Myriam Sassine (who also acted as a producer on Aris's documentary), whose infectiously jovial nature only takes a dip when genuine production problems arise. And boy, do they arise. “I feel I am in Lost in la Mancha,” she says just seconds after I started having flashbacks to Keith Fulton and Louis Pepe’s documentary portrait of the collapse of Terry Gilliam’s The Man Who Killed Don Quixote. I’m not about to start listing the mounting series of issues that delay and potentially cancel the start of shooting (that’s best seen in the film, though I will reveal that I muttered, “you have to be kidding me!” at least once), but a couple do warrant mention nonetheless. The first is how easy it is, given the devastation caused by the explosion, to forget that this occurred at the height of the Covid 19 outbreak, which brings with it the ever-present threat of a sudden lockdown, which potentially threatens the whole production when the cost of isolating everyone involved is totted up, and disrupts the schedule when the virus infects both of the twins who have been cast to play the main characters’ daughter. Then there’s lead player Saleh Bakri, a Palestinian actor who is forced, because “the Zionists prohibit you from moving freely” to take a seemingly preposterous series of flights to cover what would have taken about 90 minutes by car. The Covid restrictions again play their part here, and tensions really mount when it becomes unclear whether, even after all of his travelling, his Palestinian passport will permit him to enter Beirut after all. And let’s not forget Akl herself, whose complete commitment to the project and determination to overcome whatever fate throws at her had me rooting for her at every twist and turn.

As Akl’s friend and past collaborator, Aris is able to get close to his subjects and stay with them for the duration of the project, however it eventually turns out (I’ve deliberately not named the film they are trying to make to avoid potentially spoiling the outcome for those with twitchy IMDb fingers). His camerawork is unobtrusive and character-focussed, and is supplemented by some powerful news footage of the protests against the government that erupted in the explosion’s wake. One snippet that particularly hit me observes a furious woman holding up her phone to one of the soldiers charged with keeping order and bellowing at him to look at the wreckage that was her home. Also telling is the inclusion of shots from a video diary kept by Bakri as he undertook a frustrating journey that he did not know if he would be able to complete.

Given how much footage Aris must have shot during the course of this story, I did wonder how a longer cut of the film might have played. The timespan covered in the final third in particular feels a little like a highlights reel, followed by a brief but still tense reminder of how the after-effects of the explosion could still have a damaging impact on the production. But in the end, the decision to keep the storytelling tight and focus on the struggles the filmmakers faced is what makes Dancing on the Edge of a Volcano such a consistently riveting watch. Anyone who has tried to get an independently funded feature off the ground knows how difficult the process can be, but the determination and commitment shown here, when the process is further complicated by disasters – both local and international – that seemed to be queuing up to deliberately obstruct the filmmakers, is genuinely inspiring.

As a side note, I was fascinated by the multi-lingual nature of the conversation at the first open-air production meeting we see, where whoever is speaking is able to drift effortlessly between Arabic, French and English, sometimes during the course of a single sentence. It brought back memories of my first exposure to the cinema of Satyajit Ray, where characters would likewise move almost invisibly between English and Bengali several times in a the same sentence.

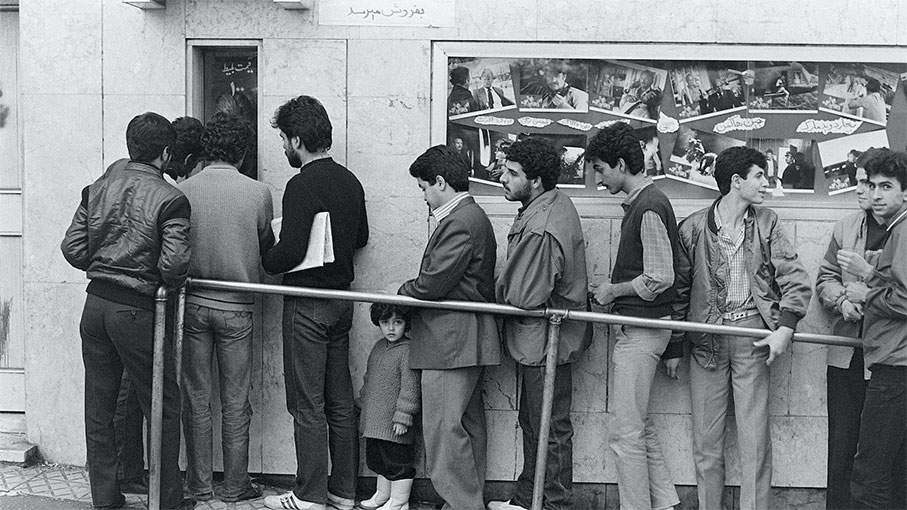

It’s almost a given that if you frequent a site like ours then you’re a movie enthusiast, and with our primary focus being disc releases, there’s a good chance you’re also a bit of a film collector. For some, this means nothing more than a single shelf containing Blu-rays of their favourite titles, while for others this can mean a whole shelving unit or in my case, a whole series of units in various rooms, plus a chest of draws crammed with thousands of review DVDs in paper sleeves that were sent to us in the days when we could get up to 20 of them a week. Either way, I’m sure these movies are precious to you. Now imagine if a populist zealot conned their way to power (and we do have them, you know – some are worryingly in government already) and decided to blame movies for all of the evils of the world and outlawed them, or at least the ones that didn’t meet very specific criteria. Films like the ones in your collection. Then imagine that to keep you from corrupting your children, it banned the ownership of movies in any shape or form and decreed that anyone caught in possession of even the tamest title would be arrested and all of your films confiscated and destroyed. If, by chance, you had removed them from your home and hidden them elsewhere, imagine being tortured repeatedly by the secret police to reveal their location, knowing that they will be destroyed and that you may never be able to replace them. Now picture going through all this at a time before the internet was really a thing, and physical media was the only way to own and watch films of any description. Welcome to the world of Iranian movie devotee Ahmad Jorghanian.

In order to tell Ahmad’s story, the now London-based Iranian filmmaker Ehsan Khoshbakht first needs to tell his own, and it’s a captivating one. Born just two years after the 1979 Iranian revolution, he fell in love with movies at probably the worst time in his country’s history, when its new fundamentalist rulers were banning and censoring films and setting fire to cinemas, and film prints were being wiped to strip them of their silver. And film was so much more than a casual interest for the young Ehsan, who on being given the present of a film frame at the of six, fashioned his own projector to screen it in the dark under his bed for himself and his sister. He soon began arranging screenings of any film material he could get his hands on for local kids, and at the age of just 17, started a film club to digitally project the many movies he had surreptitiously taped (satellite dishes were also banned and destroyed if discovered) to a wider audience, aware that a member of the secret police was attending many of the screenings. I’ll leave it to Ehsan’s film to reveal how this noble endeavour was brought to a soberingly premature close.

Once installed on an architecture course in Mashhad, he was soon back organising digital screenings of films. Having previously read about Ahmad – a legend in the world of film collecting who had effectively gone underground after the revolution – and tried to unsuccessfully to contact him by phone, he finally gets through and Ahmad agrees to start sending him film prints for his screenings. This has a transformative effect on Ehsan – “The first time I saw Chaplin on film, I cried,” he admits after his first exposure to the comedian’s work on celluloid rather than VHS tape. A tad ironically, he still had to censor these films before screening them to remove any behaviour – which could be as innocuous as a kiss – that might attract the attention of the authorities. Once, when the film arrived too late for him to check it, he sat by the projector with a piece of board ready to mask out any potentially problematic content. His requests to meet Ahmed were repeatedly deflected, then one day Ahmed called him and invited him to Tehran to visit him. Once again, I’ll leave the specifics of what happened when the two men met for the film to detail, but their time together dominates the film’s second half and will likely have every film lover open-mouthed and watery-eyed with amazement and admiration.

Up to this point, the story has been told with a combination of video material shot at the time (full marks for the first-hand record this provides of Ehsan’s film-club screenings, including the one that ultimately saw it closed down), news footage, and lovingly shot re-enactments of Ehsan’s childhood film adventures that would not be out of place in Cinema Paradiso. What proves essential to the story’s second half, but still surprised the hell out of me, is that Ahmad not only allowed Ehsan to shoot video in his film-reel-crammed apartment, but was willing to be interviewed on-camera by him as well. You have to remember that when this footage was shot, it was still illegal to privately own films, and at this point Ahmad had amassed over 5,000, plus a slew of pristine film posters (I SO wanted to go through these myself) and thousands of promotional stills in various states of decay. He had already been arrested twice and tortured because of his obsession, so I was left wondering what Ehsan told him he was going to do with footage that would instantly incriminate him if publicly shown. That said, for the sake of the story being told here, I am so glad that Ahmad allowed Ehsan what looks like free reign with his camera, as to hear Ahmad speak about his long-standing passion for cinema, and to see rather than simply be told about the sheer volume of films and memorabilia he had collected of the years, takes this extraordinary story to another level.

There were times watching Cinema Underground when I was reminded of Shivendra Singh Dungarpur’s similarly titled 2012 documentary, Celluloid Man, another tale of a devoted individual’s love of cinema and determination to preserve celluloid copies of films that were being destroyed, though in that case it was due to callous indifference rather than fundamentalist censorship. But the incorporation of autobiographical content and Ehsan’s very personal involvement with his subject results in an even more intimate work that proves every bit as eye-opening and compelling as Dungarpur’s film, and is ultimately every bit as inspiring and sobering. Perhaps Ehsan’s trump card is his own quietly delivered but poetically composed narration, one whose command of the English language frankly puts a good many of us native speakers to shame. Talking of the Middle Eastern war, he says, “An eight-year war with Iraq was sucking the country dry. Military marches and religious chants were in the air. The soundtrack of death in the Dolby Surround of grey alleys.” Later, when a false dawn appears to be emboldening protestors and he was able to expand the range of films he was able to screen, he recalls, “As the streets were reclaimed, I reclaimed Antonioni and Walsh.” But my favourite comment comes as he ruminates on the nature of celluloid, the material on which film imagery is printed: “I realised the images are captured on a matter which is partly composed of the remains of people before us, who have nourished the soil from which the ingredients of celluloid are extracted. Celluloid is us, plus the plants. That’s why autumnal trees and blood vessels appear on decomposed films. We return to nature, only to come back, this time projected.” Wow. It’s a remarkable achievement that everyone who loves film should make it their mission to see.

Dancing on the Edge of a Volcano is is screening next at the London Film Festival on:

Thursday 12 October 2023 at 18:20 at BFI Southbank, NFT3

Monday 09 October 2023 at 20:45 at Curzon Soho Cinema, Screen 2

Monday 09 October 2023 at 21:00 at Curzon Soho Cinema, Screen 3

Celluloid Underground is screening next at the London Film Festival on:

Saturday 14 October 2023 at 20:00 at Curzon Soho Cinema, Screen 1

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/2020_Beirut_explosion

|