| |

"Cinema started as a wonder and a magic. That is the way I felt during my childhood. Later it became a kind of obsession and finally a passion. But now, looking back, I find cinema is very much a part of me and my life. I understood the world and the people much better through my long journey with cinema. The way I look at cinema is the way... I understand people much better now and the world, and it has opened up my vision of life itself. So I consider, look at cinema as life itself." |

| |

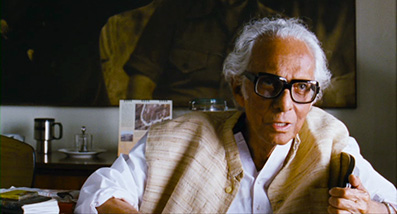

P.K. Nair |

| |

"At night screening in Main Theatre, we used to all eat quickly and stand outside and we used to wait for P.K. Nair to come. And then there was a hush, 'Oh Nair Saab is coming, Nair Saab is coming.' It was almost like the Cinema God had arrived!" |

| |

Film director Vidhu Vinod Chopra on P.K. Nair |

| |

"He was so intimate with films. And he was smelling film, he was eating film, he was drinking film. That was he; Nair." |

| |

Film director Mrinal Sen on P.K. Nair |

If you don't live in India, you'll may well be unaware of the key role a man named P.K. Nair played in the development of modern Indian cinema. Actually, there's a pretty good chance you'll not have heard of him even if you do live there. In an industry where the spotlight falls primarily on actors and directors, the work of equally dedicated men and women in less prominent roles is too often sidelined and even forgotten. Yet prominent members of India's filmmaking community talk about Nair with a respectful blend of gratitude and awe. So who, exactly, is Paramesh Krishnan Nair?

From his early days, Nair had a passion for cinema, and I'm talking about the sort of passion that dominates your waking hours and eats up your free time. Sound familiar? You don't know the half of it. Nair was born and raised in Thiruvananthapuram and his love affair with films began at an early age, when he used to sneak out of the house after his family had gone to sleep to catch late film performances at a nearby cinema. His parents wanted him to become an engineer, but after graduating in science from the University of Kerala, he left for Bombay with dreams of becoming a filmmaker himself. But something about the physical process of planning and making films just didn't sit right with him, and in the course of his studies he came to realise that he was probably never destined to sit in the director's chair.

Then in 1961, on the advice of Jean Bhownagary of the Films Division of India, Nair applied for to work at the newly formed Film and Television Institute of India (FTII) in Pune and secured the post of research assistant, and it's here that he was to discover his true calling. In this role he was instrumental in setting up the Institute's film archive, and over the next three decades he corresponded with a range of other archives around the world and personally tracked down prints of films from India's cinematic past, some of which were once thought lost to posterity. By 1991 the archive held over 12,000 films, 8,000 of them Indian, the rest from all over the world, a task and a half in a country where film preservation was once seen as irrelevant. As Nair himself says during the course of this documentary, "Nobody thought cinema in this country was part of our cultural heritage. They treated it as a commodity or means of leisure time entertainment for the so called illiterate masses."

To suggest this is a specifically Indian issue would be wide of the truth, for while other national film archives were already in existence by the time Nair began his monumental task, it's only relatively recently that their work has been fully acknowledged and appreciated. It's an issue I myself wasn't really aware of until the early 1980s, when Martin Scorsese gave a lecture at the London Film Festival (I'm working on distant memory here, but believe this to be the case), to highlight the sometimes shockingly poor state into which prints and even negatives of great and important films had been allowed to descend. Not long before this lecture I had direct experience of one of the films he used as an example, when I attended a screening at the National Film Theatre (now BFI Southbank) of Vincent Minnelli's 1956 Lust for Life. Despite being shot on what was very likely Kodak Eastmancolor stock (Metrocolor is credited, but all that means is that the film was processed in MGM's laboratories) and being a portrait of painter Vincent van Gogh, famed in part for his vibrant use of colour, the grimly faded print was only a couple of notches short of being re-categorised as monochrome.

Such neglect was not confined to pre-1960 films. Just a few years ago, UK based distributor Hong Kong Legends were involved in resurrecting some of the great martial arts films of the 1970s, a task made all the harder by the poor condition of some of the prints and negatives. That such relatively recent films could have fallen so quickly into disrepair may seem bemusing from a modern perspective, but the simple fact is that the Hong Kong studios that had made these films never envisioned them having a life beyond their first run release. As actor/director Kamal Haasan says in this very documentary, "We make non-degradable plastic material, but we have unfortunately have made our art, especially cinema art, as bio-degradable material."

The concept of even preserving a film at all in any condition seems only to have occurred to many studios when the arrival of television offered them the chance to sell their past product to a new vendor and audience, though in the early low resolution days of the medium this did not require the film prints to be in anything close to pristine condition. It's all too easy to forget just how much things have changed in the past twenty years or so. In my youth, I was conditioned to seeing films in the shabbiest of shapes when they were screened on TV – the contrast was usually weak, the detail indistinct, the colours washed out, widescreen films were cropped to 4:3, and the image would often be dancing with dust and dirt. Yet if almost any film from the post-silent era appears on DVD, Blu-ray or even TV today, we expect the contrast to be solid, the colour to be strong and the image itself to be clean of dust and damage. This transformation didn't take place overnight, and long before Scorsese's call to preservation arms, passionate visionaries like P.K. Nair, Henri Langlois at the Cinémathèque Française and Ernest Lindgren at the BFI were tirelessly working to preserve films for the benefit of those who had yet to comprehend the importance of their work.

But there's more. As well as building the archive, Nair also hosted screenings of the films for the FTII students, many of whom would go on to be filmmakers themselves. Young men and women whose film experience had previously been restricted to home grown cinema and Hollywood imports were suddenly exposed to work of filmmakers such as Ingmar Bergman, Kurosawa Akira, Pier Paolo Pasolini, Andrei Tarkovsky, Andrei Wajda, Robert Bresson and Ozu Yasujiro, as well as the back catalogue of imminent Indian filmmakers such as Satyajit Ray, Raj Kapoor, Mrinal Sen and Guru Dutt. For those who eagerly attended the screenings, this was life-changing stuff, opening their eyes to the true possibilities of the medium in which they were soon to carve their own distinctive careers.

Director Shivendra Singh Dungarpur was one of those students, and having made over 450 commercials and produced a range of short films and documentary works, he decided that his first feature documentary should be a portrait of the man that had so influenced his development as an aspiring filmmaker. Nair himself was willing, but had retired from his position of director of the archive in 1992, and it was important for Dungarpur that he be able to film Nair in the location in which he had spent the best part of his working life. It should have been straightforward but proved anything but. For reasons that are not completely clarified here, following his departure from the Institute, Nair was effectively shut out of the archive he had been instrumental in creating. It took Dungarpur a full year and eleven separate visits to the Institute to secure permission for him to film Nair in his natural habitat.

Watching the results of his endeavours, I had to salute Dungarpur's tenacity, as his film is all the richer for this material. And what material it is. Shot over the course of several visits by eleven cinematographers on a variety of 16mm film stocks, the footage is lit and composed as if for a premium dramatic feature. Coupled with Nair's now unhurried, walking stick-assisted movement, such imagery perfectly captures the almost mythical regard in which Nair is held by those whose lives he influenced and transformed. Indeed, there are even a couple of dolly shots of Nair watching films in the Institute's viewing theatre that would not look out of place in Cinema Paradiso.

The two-and-a-half hour length on paper may seem to be a little excessive for such a documentary, but it's easily justified by the scope of the story and the sheer range of interviews that Dungarpur has secured, many of which have been cut down to a single and often brief contribution. But every one of them adds something to this beguiling portrait – the quotes reproduced above are just a small sampling of those I noted down on my second viewing for potential use within this review. There's not a wasted recollection or anecdote here, and I have a feeling that if Dungarpur had been able to include every bit of worthwhile interview material then Celluloid Man would have run for the good part of a day. Perhaps the most unexpectedly inspiring interviews are not with actors or filmmakers, but with the two village farmers who attended the public screenings that Nair helped set up for those who would normally never have access to non-mainstream cinema, who fondly recall their first experience of watching classic films like Rashomon and Pather Panchali.

Structurally, the film deviates from the obvious biographical path, making us aware of the regard in which Nair is held but taking time to reveal the full details of why. His journey from enthusiastic young film fan to his country's premiere film archivist is also teased out in disarmingly non-linear fashion, and we're an hour and a half in before the film even touches on his private life. It's a segment initiated by director and former student Balu Mahendra, who recalls his concern that Nair's passion for his job was causing him to neglect his family. This is both backed-up and balanced by Nair's daughter Beena, who recalls her father's passion for his work without a trace of bitterness, but admits that they've become a lot closer since he retired and the two are finally able to spend quality time together.

Not all the revelations here are heartening, however. Grim figures are provided on the sheer number of films that have been lost, and as with other countries, the older the film, the slimmer the chances that it has survived (of the 1,200 Indian films made in the silent era, only 10 have been rescued by the archive to date). And yet prints of films from all ages continue to be destroyed. This cultural vandalism is graphically illustrated by a sequence that will chill the hearts of all true film fans and actually made me yelp with horror, as 35mm film prints are sold on market stalls for about £1 a kilogram, piled up in storerooms and spooled into a chemical bath to strip them of their silver content, transforming the results of passion, hard work and creativity into a few grams of metal and seemingly endless strips of clear sprocketed celluloid. As director Dungarpur soberly reflects, "Here I am now, surrounded by film cans and films, the images I grew up watching being washed away and turned into silver for coloured bangles." There are also some troubling suggestions about the condition of the archive since Nair's departure, with the claim made that films are no longer stored at the correct temperature or humidity or in dust-free conditions, although there are no interviews with the current archival staff to either back this up or refute it.

Nair himself clearly misses what he still regards as the best years of his life, a sense of loss subtly evident in the unwaveringly serious nature his interview material – only in the two brief sequences in which he and three of his contemporaries talk film in a café do we get to see the smiling and warmly enthusiastic man that we can presume so beguiled the students back in the day. But this in no way discolours Nair's extraordinary achievements as an ambassador for cinema and a protector of its history. And In telling Nair's story, Dungarpur also provides a fascinating dip into the history of Indian cinema, introducing those of us with only scant knowledge of the subject to a number of key filmmakers, and illustrating Nair's memories with tantalising clips, the sort that make you want to hunt out the films in their entirety.

No question about it, Celluloid Man is an enthralling, educational and ultimately inspiring portrait of a remarkable man who probably never regarded himself as such. A level-headed and meticulously researched hymn to the unique pleasures of cinema and the importance of film preservation, it also stirred fond memories of the man who first fired my own gradual awakening to what Martin Scorsese once called the full palette of film experience. His name was Paul Harrison and he ran an evening class in which he screened an impressive range of films from around the world for willing students on the Photography, Film and Television course on which I was enrolled. Astonishingly, in retrospect, the class was not mandatory and only a handful of students ever attended. But what I saw there over the course of three years changed my perception of the possibilities of film forever. Mr. Harrison, wherever you are right now, I salute you and those like you, men and women who, in the words of the venerable Mr. Nair, when they see a film they like, want to share it with others.

Shot on a variety of purchased and donated 16mm film stocks (which are listed in the accompanying booklet if you're interested), the tone of the image does vary accordingly, in its colour saturation, the level of grain and even the contrast. What does surprise is that – gorgeously lit monochrome footage of Nair aside – the variances are for the most part relatively small, given the inherent differences in the look of Kodak and Fuji colour film, both of which were used here. The best material has that uniquely warm look and pastel colour that you only seem to get with 16mm film, and the level of detail is often impressive, particularly given that this is a DVD. I was actually rather pleased to see a couple of small hairs that were doubtless caught in the gate during filming, which served as a reminder that this was shot on film, as a portrait of a man with a love for celluloid could only be. The picture is framed 1.85:1 and is anamorphically enhanced.

Both Dolby 2.0 stereo and Dolby 5.1 surround soundtracks are on offer, and, surprisingly perhaps, I'd go for the stereo every time – it's louder, crisper and more lively than it's comparatively flat 5.1 brother. No surprise that the stereo was the original mix.

One thing that did irritate me a little at first is the presence of English subtitles on interviews that are largely conducted in English. It's something I've seen a few times on TV documentaries when interviewees are speaking English but are of Indian, Jamaican or Chinese descent. It's always struck me as rather condescending, an assumption that we won't be able to understand our native language if it's delivered in an accent we might regard as foreign. Certainly I had no problem at all with the clarity of the interview material here, even when I intermittently looked away from the screen to confirm it. The thing is, you can't turn the subtitles off, which struck me as odd for a distributor like Second Run, and I began to suspect that the subtitles had been added at source, which seems to be confirmed by the closing credits. I soon got used to their presence, however, and was able to quash my autonomic tendency to read what the interviewee was saying before they actually said it. Doubtless these subtitles were added on Dungarpur's direction to make the film as accessible as possible with audiences whose ear for accents is perhaps not as finely tuned as mine (though this did make me wonder why he did not also to subtitle his own voiced commentary), but I soon found good reason to consult them myself, as unfamiliar names, places and film titles were rattled off at conversational speed – were it not for the subs, I'd never have caught them.

In Conversation with Shivendra Singh Dungarpur (12:34)

A perhaps too brief but still engaging chat with the film's director Shivendra Singh Dungarpur, who talks about his early attraction to cinema, his initially reluctant enrolment at the FTII, accompanying Nair back to the archive ("when you're walking with him amongst those film cans he sort of feels that they are his children") and the proclamation from Institute officials that Nair should not be allowed in there, and his decision to make a film about the man who so influenced his life and career.

Booklet

"Why write about this film, one of the best movies ever made about cinema?" asks Mark Cousins at the start of the two-page essay that opens this booklet, then answers his own question when he states quite simply, "Out of excitement, certainly." This useful overview precedes what has to be the best extra here, a series of excepts from Shivendra Singh Dungarpur's diary of the production, which provides a welcome insight into the work that went into the film, the technical and logistical challenges, and its frustrations and pleasures. An enthralling read.

What more can I say? A superb documentary portrait of one of the unsung heroes of world cinema that should be considered essential viewing for anyone even remotely interested in the history and even the future of film. But you shouldn't need me to tell you that – if you have a love affair with cinema then this should already be on your shopping list. Great film, great transfer, and a fine accompanying booklet. Highly recommended.

|