|

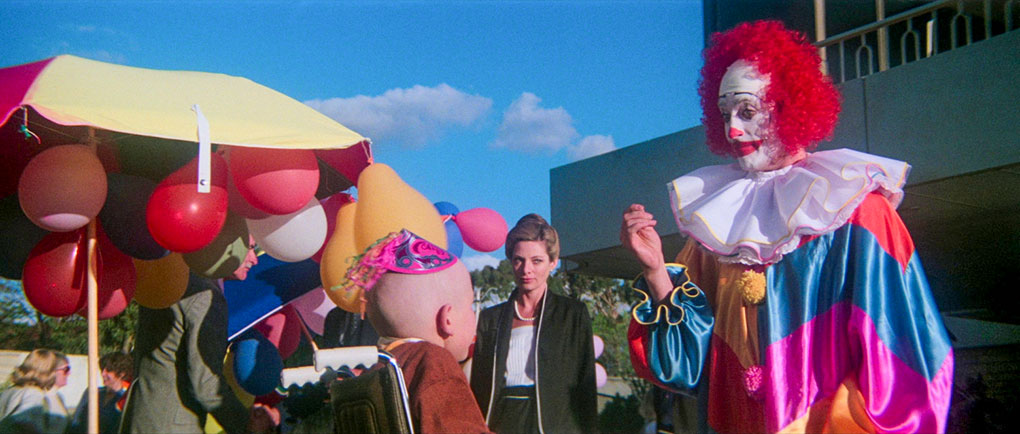

Nick Rast (David Hemmings) is an up-and-coming Senator being groomed for the role of deputy governor. However he and his wife Sandra (Carmen Duncan) are facing tragedy: their nine-year-old son Alex (Mark Spain) has leukaemia and doctors are unable to do more for him. Enter the mysterious Gregory Wolfe (Robert Powell), a faith healer who seem to cure Alex. The Rasts take Wolfe into their home, but Nick soon becomes suspicious of Wolfe's hold over his wife and son...

Following Snapshot (1979), director Simon Wincer and screenwriter Everett De Roche looked to work together again, having been dissatisfied with the rushed schedule of the earlier film. Of several ideas De Roche pitched, they settled on The Minister’s Magician, an update of the Rasputin legend. (Rasputin’s antagonist was Tsar Nicholas, hence the name of Hemmings’s character: spell the surname in reverse.) Antony I. Ginnane, for whom Wincer and De Roche had worked on Snapshot, came on as producer. At first Wolfe was a priest in the script, but Ginnane suggested turning him into the faith healer be became, to avoid possible offence in Catholic countries who, as it turned out, were the biggest markets for the finished film.

Due to funding from the newly-established Western Australian Film Council, Harlequin was shot in and around Perth, much of it in a studio built inside a warehouse, beginning on 20 August 1979. A key location was the home of Alan Bond, then one of the richest men in Australia and in 1997 imprisoned on corruption charges. The two centres of the Australian film and television industries at the time were Melbourne (where Ginnane was based) and Sydney. The other state capitals were much less often used. The previous feature film shot in Perth was Nickel Queen, back in 1971. Because of this, local actors mostly worked on stage, but several of them were cast in smaller roles and as extras. Ginnane aimed at a wider audience than Australia and for that reason he made a point of bringing in actors from overseas to aid international sales. The two leads were British. David Hemmings had worked for Ginnane the previous year in Thirst, and his company Hemdale provided some of the funding for Harlequin. (Hemmings would go on to work for Ginnane again, as the director of Race for the Yankee Zephyr and The Survivor (both 1981).) The role of Wolfe was originally intended for David Bowie, but Robert Powell was a big name due to playing the title role in the Franco Zeffirelli-directed miniseries Jesus of Nazareth (1976) and this as it turned out helped the box office in those Catholic countries, Argentina especially. Broderick Crawford came out from the USA to play a role originally suggested for Orson Welles, that of political fixer Doc Wheelan. Crawford was an Oscar-winner for All the King’s Men (1949) and Harlequin was one of his last roles, before his death in 1986. The only one of the principals who was actually Australian was Carmen Duncan, from New South Wales. Thirty-seven at the time of shooting, she was a relative veteran in Australian film, having appeared in some of the few local productions made in the 1960s, such as Don’t Let It Get You (1966 – actually one of the very few New Zealander films made between the silent era and the 1970s, though partly shot in Sydney) and You Can’t See ’Round Corners (1969, based on the television serial of the same title). There are some familiar Australian faces in the supporting cast, such as John Frawley as the Rasts’ doctor. Making his screen debut as one of the young boys on the raft towards the end is Perth native Jeremy Sims, who has also since become a director (Last Cab to Darwin, Rams and others).

This was another Ginnane production which did its best to de-emphasise any Australianness. It might have been shot in Western Australia, but it's not set there. Phone ringtones are American and cars drive on the right even though the number plates are still West Australian. The political system in the film is more American than Australian. On the other hand, the plot-inciting disappearance while swimming of Rast’s political opponent at the start of the film evokes the real-life drowning of Australian Prime Minister Harold Holt in 1967, his body swept out to sea and never recovered. However, this plot detail certainly wouldn’t preclude international audiences even if it had greater resonance for local ones. (If you’re wondering why the Rasts’ television set is showing the famous BBC Test Card F, with young Carol Hersee playing noughts and crosses with a clown doll, the card was used in Australia and some other countries as well as in the UK.)

Compared to Snapshot, Harlequin had a higher budget and, important to Wincer, a longer post-production schedule. The result is a polished production, with music (Brian May), production design (Bernard Hides, of whom more below) and cinematography (Gary Hansen) excellent. There’s a strong emphasis on colour in some scenes, particularly reds but also yellows and greens in a key scene set in a bathroom. The Australian film revival brought some world-class cinematographers to the forefront. Hansen could have been one of them. He won an Australian Film Institute (AFI) Award for We of the Never Never in 1982, the same year he was killed in a helicopter crash. He and Wincer make good use of Scope, with some wide framing that you would see far less often just a few years later. Then you’d see the action kept in a safe area to enable panning and scanning to 4:3 for television and the growing video market.

Simon Wincer began his career on television, working particularly for Crawford Productions on such as Division 4, Matlock Police and Homicide. He wasn’t the first Crawford’s alumnus to be picked by Ginnane to make feature films for him, for his proven ability to work fast and efficiently if the results were sometimes anonymous and workmanlike. He has worked for both media since in Australia and the US, his feature films including Phar Lap, The Lighthorsemen and, well, Crocodile Dundee in Los Angeles. Harlequin is one of his better films. It’s a slow burner, but does have some genuinely unsettling sequences, aided no end by Robert Powell's charisma. There are some logical problems in the storyline. It’s not clear why Rast's security man Bergier (Gus Mercurio) doesn't report the incident when Wolfe holds Alex over a cliff, except that there would be no story if he had. The very end is now a horror cliché and was becoming one at the time.

Harlequin did not do especially well in Australian cinemas. It was nominated for five AFI Awards, for direction, Best Actress for Carmen Duncan, editing (Adrian Carr), production design and costume design. It won none of them, the big winner that year being 'Breaker' Morant. However, the film sold overseas, being retitled rather blandly as Dark Forces in the USA in 1984. It opened in the UK (trimmed by about two minutes from the present full version) with a royal premiere, going into release the next day, according to Ginnane on forty screens in London alone doing adequate if not spectacular business. Not having been old enough to see an X-certificate film at the time, I first saw Harlequin on its television premiere on 10 August 1983, a showing sadly panned and scanned.

Harlequin is spine number 433 in the Indicator series, released on Blu-ray and UHD in a limited edition (4000 and 6000 respectively). This review is from a checkdisc of the former, though see below for a transfer comparison between the two. The Blu-ray is encoded for all regions. In Australia, the film has always carried a M rating (advisory, particularly in respect to under-fifteens). It carried a notably harsh X certificate (over eighteens only) in UK cinemas but has had a more appropriate 15 since 2003 and retains that on this release. This is the full-length version of Harlequin, running 95:45 in this transfer. The UK cinema running time was 92:46 according to the BBFC, that time presumably including distributor logos. I’m not aware what was in the two to three minutes difference between the two.

The film was shot in 35mm colour with Panavision anamorphic lenses, and the transfer in either format is in the correct ratio of 2.35:1, derived from a 4K scan of the original negative. Over to Slarek for a comparison between the Blu-ray and UHD transfers, and after that I’ll return.

Harlequin and Thirst were released simultaneously by Indicator on both Blu-ray and UHD, a pairing that feels appropriate not just for the Ozploitation connection but also for the similarity in the quality of their transfers, and the observable differences beween the image on the Blu-ray and the UHD. The colour is most attractively vibrant on the Blu-ray disc, but even more so on the UHD, where the picture is also sharper and the detail more clearly defined, as you would expect. As with Thirst, the image on the UHD feels slightly brighter than on the Blu-ray, and while the contrast is very nicely graded on the Blu-ray, the implementation of Dolby Vision HDR on the UHD expands its range, allowing more visible picture information in both the shadows and highlights on the 4K transfer. There's a shot in which this is particularly evident near the end of the film, one whose content I can't discuss without dropping a massive spoiler, but it's a static high angle shot set in a kitchen, where far more background detail is visible on the UHD, but the intentionally deep shadows cast on a figure on the left of screen are as strong as they are on the Blu-ray. The transfers on both discs are clean of dust and wear, and a fine film grain is visible. Once again, due to technical constraints, the grabs shown here are from the Blur-ray release. The soundtrack is the original mono, rendered as DTS-HD MA 1.0,. There is also an isolated score option so you can hear Brian May’s music in LPCM 1.0. English subtitles for the hard-of-hearing are available on the feature only, and I didn’t spot any errors in them.

Commentary by Antony I. Ginnane and Simon Wincer

This was recorded in 2004 for an American DVD release, as the film is referred to by its US title of Dark Forces throughout. This covers pretty all the bases, and inevitably there is overlap with the other extras on this disc. Ginnane talks about the shoot in Perth and surrounds due to funding from Western Australia, though he’s incorrect in saying that Harlequin was the first feature film shot there in twenty-five years. (Due perhaps to the local interest Nickel Queen was a bigger hit in the state than elsewhere in Australia.) He also talks about how he wanted to make films which weren’t “kitchen sink” but were genre items which could play internationally, if at the cost of much Australianness, and for more of that see his Not Quite Hollywood interview. Simon Wincer likes the Scope format, and we know this as he says so several times. (He had used it previously on Snapshot and would continue to use it in many of his later films.)

Not Quite Hollywood interviews (50:28)

Once again, Mark Hartley’s 2008 documentary provides us with interviews from many of the people involved. These are particularly of value with interviewees no longer alive, one here being a case in point. Four here, with a Play All option.

First up is Simon Wincer (20:26) who begins by giving a reason why he and others made thrillers and horror films, given that they could be made relatively easily and potentially would have a high return on the investment. He talks about his background on television for Crawford’s, after which he made Snapshot for Antony Ginnane, and his work with Everett De Roche on the idea which finally became Harlequin. Wincer is not the only person to tell stories of Broderick Crawford liking his drink and on one day coming on set with his trousers on back to front.

Antony Ginnane (21:23) spends a lot of time talking about his policy with the films he made, and particularly their marketing. He says that although he is Australian and has made films in that country, he is not interested in “Australian films”, hence the use of overseas actors and the non-specific locations and accents. Robert Powell, due to Jesus of Nazareth, was a major draw in South America where Harlequin had some of its biggest commercial successes, particularly in Argentina. It may have been different if David Bowie had played the role. As so often there is a sense of axes being ground, with Ginnane disparaging other Australian films and the funding bodies who seemed not to be concerned with making commercial films but “artistically driven” ones. A particular comparison is The Chant of Jimmie Blacksmith, which was at Cannes at the same time as Patrick – a critical success and certainly helping Fred Schepisi’s career, but commercially an expensive flop.

Next is a brief item with Everett De Roche (3:01), in which he talks of the origins of the film as an update of the Rasputin story. Given his original title, he wasn’t enthused with the eventual one of Harlequin. But then, he says, screenwriting was all about compromise, and decisions about selling the end product were taken by others long after his involvement had ended.

Not quite so briefly, Gus Mercurio (5:36) compliments David Hemmings and Robert Powell as being excellent actors and talks about how he was an unofficial minder to Broderick Crawford. That includes the story about the wrong-way-round trousers mentioned by both Wincer and Ginnane. Crawford was a big man and at one point a chair collapsed under him.

Archival Interviews

These are grouped together in a submenu, though there is no Play All option.

Archival Interview with David Hemmings and Robert Powell (6:01)

This interview took place in 1980 for Clapperboard. This was not the British children’s film programme which ran from 1972 and 1982 and which is well remembered by Brits of a certain age like myself, but was made for the Australian Nine Network. Longstanding presenter Anne Wills (often known as “Willsy”) is our host, with her pieces to camera topping and tailing the interview itself which was conducted at a cocktail party at the Town House in Adelaide. In her introduction, Wills says, “Sitting between those two gorgeous men, it was very hard to even ask semi-intelligent questions,” which makes a change from the male gaze in many television film programmes of the time. Powell says that he was sent the script in London and was immediately taken with it. Both men talk about Broderick Crawford and Hemmings describes the backwards shooting schedule, due to filming Mark Spain’s scenes with hair before those with his head shaved. “I think I’m in love with them both,” says Wills.

Archival Interview with Everett De Roche (5:29)

This dates from 2007 and is from the Australian community TV show The Bazura Project. De Roche is interviewed by Shannon Marinko and Lee Zachariah. This is a short career overview and not specific to Harlequin – which isn’t mentioned – and was conducted while De Roche was still a working writer. (Not counting the 2013 Patrick remake, where he gets an “inspired by” credit, his last work was in 2010. He died in 2014.) His interviewers describe him as one of a handful of successful Australian screenwriters, for which his reason is as he says, “staying alive, I guess”. He’s open about writing for a broad audience and talks about the difference between psychological horror films and the more “physical” kind. To put that in context, this was at a time when “torture porn” was in fashion in the genre. The films of his he talks about are Frog Dreaming, a childhood favourite of one interviewer, and Razorback.

Archival Audio interview with Simon Wincer (75:43)

This and the next two audio interviews were carried out in 1979 during the production of Harlequin, for articles which appeared in the December 1979/January 1980 issue of Cinema Papers. The interviewers were filmmaker Rod Bishop and co-creator of said magazine Peter Beilby. Here in the hot seat is Simon Wincer. This appears to be unedited, as it begins with “Side One”. Wincer talks about the differences between cinema and television, with the latter frequently having a disengaged and sometimes distracted audience and the shooting style requiring an abundance of close-ups due to the then small size of sets. Television also tends to be written to formula and was made fast, scripts being precisely timed so that pretty much everything that was written was filmed. It also had (then) restrictions on content and apart from on the ABC, small-screen drama was structured around the need for commercial breaks. On the other hand, cinema was something you actively had to go out to see, and sitting with an audience in the dark enabled more concentration, in theory anyway. Regarding Harlequin, Wincer talks about the intentionally non-specific setting. Robert Powell arrived just before the finale was shot, due to the backwards schedule because of the demands of Mark Spain’s hair, and also because Powell had just become a father for the second time. He talks about Orson Welles being considered for the role Broderick Crawford finally played, which would have been fascinating if that had come about.

Wincer talks about his shooting style, liking a lot of camera movement, and front-projection was used for some of the special effects sequences. Adam Bond’s Perth residence, where much of the film was shot, fitted the script requirements pretty much exactly. Wincer goes on to talk about his experiences on Snapshot, with his disagreement with Ginnane about the twelve minutes taken out before release (the wrong twelve minutes, he maintains). Given the rushed post-production schedule for that film (one week) he had it in his contract for eight weeks for Harlequin. He also talks about his television work with Everett De Roche, making some of the same points about the small screen versus the large as above. He also claims that feature films for television on the whole “don’t work”. Wincer is open about wanting to make commercial films. He’d watch arthouse films but has no desire to make them.

Archival Audio interview with Jane Scott (51:51)

Also by Bishop and Beilby for the same Cinema Papers issue, this time we hear from associate producer Jane Scott. (She went on to become a producer, her films including Crocodile Dundee (1986) and its sequel and Strictly Ballroom (1992). She won an AFI Award and was Oscar nominated for Best Picture for Shine (1996).) Scott begins by defining what an associate producer does and how it differs from a production manager, though the two roles often overlap and will differ due to the involvement of the producer. Much of her role involves the day-to-day handling of the finances in order to keep the film within budget. On Harlequin, she had seven weeks of pre-production, five of them in Perth, and she talks about the difference in budget between shooting there rather than in the State of Victoria as they might have done. Scott says that some departments always complain about not having enough money, art and music particularly. She also thinks that many Australian productions were too low in budget, though there were ways that films could be made more cheaply, using local casts and crew rather than flying people in and putting them up in hotels. The way films are financed is not something you hear about very often, and so this is very interesting, if undoubtedly current as of forty-five years ago.

Archival Audio interview with Bernard Hides (34:49)

Also for Cinema Papers, production designer Bernard Hides answers the question as to when he was brought on to the film with a wry “too late”, which was five weeks before production. The initial studio he saw in Perth was too small. The special effects were the reason why a studio needed to be used instead of an existing house; he recalls a problem with Patrick where a set had been built inside just such a house. Hides talks about the need for collaboration with the director and cinematographer and this was limited on Harlequin due to Simon Wincer leaving for Sydney for a while and Gary Hansen not being assigned until relatively late and still being in that city so communication being by phone. (Hides had more collaboration on The Odd Angry Shot (1979), which was directed by Tom Jeffrey and photographed by Donald McAlpine.) Effectively he had created a two-storey house inside a studio, partly to enable the shots that Simon Wincer was looking for and also to give him possibilities of access from one room to another or up and down stairs. He also had to suggest the character of the Rasts based on the home where they lived. She was the one with the money, so the décor mostly reflected her tastes. Unless the film has a historical or fantasy setting, the production designer is likely the most undersung of the principal crew, so this interview gives a lot of insight as to what they add to the films they work on.

More than Magic (15:34)

Stephen Morgan continues his series of appreciations of the Ozploitation films Indicator have released. He talks about how Harlequin is an example of the “transnationalisation” of Australian cinema at the end of the 1970s and start of the 1980s, when at the same time other films were explicitly tackling Australian national mythology and history (My Brilliant Career (1979), Gallipoli (1981) for example). Morgan also sees the film as a mix of supernatural content with the kind of political thriller such as The Manchurian Candidate and, later and more paranoid, All the President’s Men. The ambiguous setting of Harlequin – not quite America, but not really Australia either – is something that has continued in many later genre films, for example the American-set if Australian-made work of such as the Spierig Brothers and James Wan and Leigh Whannell. However, there are exceptions to this, such as the explicitly Australian horror film Wolf Creek (2005). Morgan also talks about the making of Harlequin, especially its being shot in Perth.

Destruction from Down Under (15:33)

This “Ozploitation Retrospective” dates from 2018. Kim Newman begins by saying that his first sight of what would now be called Ozploitation were the comedies which came out in the early 1970s, which he describes as akin to the British Confessions films. (Maybe so with The Adventures of Barry McKenzie (1972) and certainly Alvin Purple (1973), but I wouldn’t describe Petersen (1974) that way.) However, later in the decade, he started to see horror movies coming in from Australia, particularly noting the name of Everett De Roche in the credits of many of them. At the same time, more “respectable” films were opening in cinemas, from directors such as Peter Weir and Fred Schepisi. After Mad Max (1979) came a boom in more action-oriented fare. Some familiar faces began to establish themselves in front of the camera: Newman mentions Bruce Spence and David Argue, plus older actors like John Meillon and Charles Tingwell. (His later listings of international leading men who are in fact Australian includes Russell Crowe, a New Zealander even if he has lived and worked extensively in Australia.) He is in error by saying that the UK didn’t have the American redub of Mad Max – that is what played in our cinemas and my first viewing was of that version. Newman discusses the use of the Australian landscape as a “magical” place, citing Walkabout and the British film The Shout, which makes use of Aboriginal legends. As this is a featurette on a previous disc release of Harlequin, we go on to talk about the film itself, which Newman missed in the cinema and first saw either on VHS (possible, as it had a pre-certification UK release in 1982) or the same TV broadcast I saw. Newman doesn’t see Harlequin as really a horror film but a political thriller with mystic overtones. He also discusses the ambiguous setting, comparing the film with Canadian productions which imply that they are set in the US. Another comparison is the film Powell later made for Ginnane with Hemmings directing instead of acting, namely The Survivor (1981). Newman does see Harlequin as having an unusual tone and more performance-based than story-based than is usual for genre cinema.

Trailers (6:21)

With a Play All option, we have three trailers. The first is a rather spoilerific Australian one (2:55) and another more concise Aussie option. As you can see from the running times (1:43), the US trailer is identical to the latter, other than changing the title cards from Harlequin to Dark Forces.

Image galleries

As usual with an Indicator release, these are navigated via the forward and back buttons on your remote. The first gallery comprises sixty images: stills (black and white and colour), the press kit and poster designs from more than one country, including Greece and the UK. There are two other galleries: the dialogue continuity script (twenty-five images, two pages for each) and the original script (sixty-two, again with two pages per image), with some crossings-out and handwritten amendments presumably by Everett De Roche.

Book

Indicator’s book, available with this limited edition only, runs to eighty pages.

It begins with “Not Quite Australia” by Julian Upton, who starts with discussing Rasputin and his appearances in popular culture, beginning in 1917 with the US-made Rasputin, The Black Monk appearing within a year of his being cold in the ground. Further films appeared in the US and Germany and in the UK from Hammer Films in 1966 (Rasputin The Mad Monk, starring Christopher Lee). There was also Boney M’s hit single from 1978, only a year before the present film was made. Upton then goes on to Harlequin, with an overview of the film’s making, beginning with Simon Wincer and Everett De Roche reteaming after the, to them, unsatisfactory Snapshot, and discussing Ginnane and Wincer’s intentions to “internationalise” (that is, Americanise) the setting. Robert Powell was a better choice than the original one of David Bowie, and Upton sees Wolfe as a more sinister counterpart to Powell’s previous role as Jesus, as a “wayward, time-travelling, glam-rock twin”. Upton does think that Harlequin could have made more of its Australian locations, with maybe John Meillon or Bill Hunter playing Wheelan, and the dislocation has maybe prevented it from having a stronger place in Australian cinema. However, it’s “just too punchily made, too decently acted and, frankly, just too weird” to be dismissed.

Another Indicator release produced by Antony I. Ginnane, and another extract from his unpublished memoir Some Scenes Objectionable. He begins with Everett De Roche’s script arriving. It was immediately optioned and earmarked to be Ginnane’s and executive producer William Fayman’s next production. Ginnane goes into detail about the financing of Harlequin before hiring Simon Wincer (who had put Ginnane’s recutting of Snapshot behind him) and casting David Hemmings, who suggested Robert Powell. Broderick Crawford’s casting took the film away from having too much of a British feel. In his account of the production, Ginnane does reveal that Hemmings and Carmen Duncan had an affair, which caused issues with others on set, especially as Hemmings’s wife visited for some of the time. Ginnane talks about the completion and release of the film, its lack of commercial success in Australian cinemas attributed to audiences being unwilling to embrace locally-made genre films. Ginnane quotes some of the local critics, who gave the film a mixed reception, but clearly some of the bad reviews still rankle. The same applies to the British reviews. Ginnane does find the BBFC’s then X certificate then inexplicable (the then AA would have been more understandable). He also talks about Harlequin’s fate at the AFI Awards, finding it outrageous that Brian May was not nominated for Best Score. He then talks about the film’s US release and retitling and its struggle to be pitched as a horror film with a MPAA PG rating. As with previous extracts from these memoirs, this is long and at times a little dry, but valuable as first-person testimony of Australian filmmaking at the time.

Over to Cinema Papers again, and an interview of Ginnane by Peter Beilby and Scott Murray from the January-February 1979 issue, before production of Harlequin had begun. This is a lengthy career overview, five years after he had previously been interviewed in the same magazine. So this begins with Fantasm (1976), with which he moved from film distribution and production to production. (He had previously written, produced and directed Sympathy in Summer, shot in 1968 and released in 1971, his only directing credit while he was a university student. He doesn’t mention this, and it’s unavailable nowadays.) Fantasm was a sex comedy which he designed to be made on a low budget and he approached Richard Franklin to direct, which he did under the pseudonym Richard Bruce. The result was successful, its follow-up less so. Blue Fire Lady was a children’s film and was successful but returned less because much the audience would have been bought half-price tickets. That was not the case with Patrick, which followed. Ginnane immediately takes no prisoners by calling Everett De Roche one of the best writers in Australia and saying that most of the “accepted” screenwriters were no good, and he has a go at film critics as well. Ginnane discusses the marketing of his films, and the role that Cannes played, including the possibilities of selling his work to the US majors. He also has a lot to say about production/distribution/exhibition organisations in Australia. He rather gloomily ends by saying that the halcyon days of the Australian film industry are over, and fewer people would be making films there in around five years. (As of 1979 – I wonder if he would have agreed with himself then?)

Also in the book are cast and crew listings and plenty of stills.

Harlequin was one of the better films to come from Antony Ginnane’s company. It holds up well enough despite some flaws and the more-or-less anonymous setting. Indicator’s presentation is as good as you should expect.

|